On February 1st, PeerJ announced that all accepted manuscripts submitted to its two journals (PeerJ and PeerJ Computer Science) before the end of the month would be published for free. This promotion coincided with PeerJ’s 5th anniversary.

The response from authors was overwhelming. Manuscripts flooded in, many in the last three days before PeerJ’s promotion ended. On March 1st, in response, Jason Hoyt, co-founder and CEO of PeerJ, tweeted his enthusiasm: “Wow. More than 1,500 manuscripts submitted to @thePeerJ for peer review in February. And all for free. Way to go!” For context, last year PeerJ published a total of 1,370 papers and just 38 in PeerJ Computer Science.

Reactions to PeerJ’s free publication promotion were generally positive. Free publishing would introduce PeerJ to many new authors, supporters claim, and be helpful to those who do unfunded research. A more insightful comment — in the form of rhetorical questions — came from Angela Cochran, fellow Kitchen blogger:

What is the overall message you take from this? Is it that people don't want to pay? That an APC is a barrier for trying something new?

— Angela Cochran 🌻 (@acochran12733) March 1, 2018

It should surprise no one that when a publisher reduces its processing fee from $1,095 to zero, the result is a rapid increase in demand. The flood of submitted manuscripts simply illustrates that PeerJ is a respected publisher that creates true value for its authors. A marginal change in submission rates, in contrast, would have caused greater concern about whether PeerJ provided such value or had fully captured its potential author market.

Why would a for-profit, VC funded publisher celebrate by committing itself to a full year’s worth of additional expenses with no additional revenue?

Nevertheless, why would a for-profit, venture capitalist (VC) funded publisher celebrate by committing itself to a full year’s worth of additional expenses with no additional revenue? If we look at the past performance of PeerJ together with its recent press release, we may find an answer.

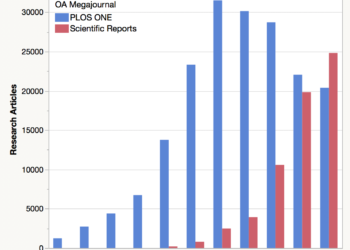

PeerJ (the journal) is not growing as expected. After launching in 2013, annual publication output doubled (103% increase) in 2014, but quickly began to slow to 70% in 2015, to 62% in 2016, to just 6% in 2017. At present, 2018 output looks very much like 2017. For PeerJ Computer Science, output looks more bleak: 45 papers in 2016, 38 in 2017, and just 5 papers to date in 2018.

While many niche publishers would be satisfied with publishing 1000+ papers per year, PeerJ must grow to the size of PLOS ONE and Scientific Reports to satisfy the financial returns demanded by its VC investors. At present, growth appears to have stalled at a fraction of these two competitors. In addition, undercutting the competition on price by a few hundred dollars doesn’t seem to have made any difference; we only see a surge of submissions when PeerJ’s price point has been reduced to zero. Moreover, while PeerJ has pivoted away from its initial pay-once-publish-for-life business model, it still retains many loyal returning authors, who cost the publisher money but do not bring in any additional revenue.

PeerJ’s free publication promotion coincided with an announcement of an overhaul of its editorial structure, adding Section Editors who will soon take responsibility of the decisions made by its Academic Editors. According to their announcement, PeerJ’s assignment of an Academic Editor was largely a random process that involved little, if any, oversight:

Ultimately it is the single Academic Editor that makes a final decision, without consultation or agreement with the community (although journal staff provide some guidance). There can be 100 Academic Editors covering one subject, each acting independently. For authors, the worry can be that there may not be consistency between decisions and it is down to the luck of the draw of which Academic Editor handles their submission.

PeerJ, like PLOS ONE, Scientific Reports, and other OA megajournals, were founded on the principle of publishing all “sound science,” regardless of its importance, novelty, or significance. In theory, an editorial model based on sound criteria should have been straightforward. In practice, it has not. A layer of editorial accountability was added to PLOS ONE in 2016, when it appointed its first Editor-in-Chief.

Adding another layer of decision-making will slow decision and publication times — a trade-off that PeerJ believes is justified. It will also further increase costs.

As explained in the HBO parody, Silicon Valley, many startup companies launch with a business model, only to pivot when they find themselves in trouble. PeerJ did this once when it pivoted from their initial $99 pay-once-publish-for-life individual membership model to an APC and institutional-support model. With this recent move, PeerJ pivots from a community-driven megajournal model to a traditional editorial-driven model. In order to successfully pivot, however, PeerJ will need to expand into new author markets.

After five years, one wonders how long investors are going to remain patient with PeerJ and whether this is PeerJ’s final pivot?

Discussion

11 Thoughts on "PeerJ Waives APCs and Pivots Again"

I think a really important lesson here is the growing recognition by megajournals of the value of centralized editorial oversight. A lot of megajournal development has been based around shedding of things journals usually include — review for significance, copyediting, etc. There seems to be enough of an audience of authors willing to forego such things to drive a successful business. But from this move (and PLOS’), it looks like editorial oversight is not something that authors are willing to do without, and a consistent and high quality review process is still an essential component of any journal.

I agree with David. Our ongoing work on the attitudes and practices of early career researchers (www.ciber-research.eu/harbingers.html) makes clear the importance of the role of editors in chief in control of choosing the right peer reviewers

One could also look/analyze PeerJ from the perspective of ‘what’s the value and influence been to science and research’, and as a change agent to make others look internally. I see many of the PeerJ articles have high citation counts, and large alternative metric scores, and I know many publishers admire and follow the work being done by PeerJ. You do raise some excellent points Phil, and give insightful perspectives that many are perhaps not fully aware of. It’s equally possible looking at PeerJ, that the VC was partly funding this as an experiment, and philanthropic support of the vision and mission PeerJ has. Community projects and pilots can also bring a vast amount of knowledge, understanding and in some cases major change and disruption. In metaphorical terms, are you betting on a horse that must win, or do you just enjoy seeing the beautiful creature take part in the race ? I do admire the fact PeerJ is agile enough to be able to test and try different models, and not be afraid to adapt (it seems like the rest of the publishing industry also gets some benefit from observing as well) … so while one view may be doom and gloom, there’s certainly another that is positive and beneficial at a wider/higher level … guess it depends if your glass is half full or half empty right ?

Thanks for your comment, Adrian. If PeerJ were run as a philanthropy, then it should have been set up as one. The Public Library of Science was set up as non-profit, so was eLife.

Yeh true, but as far as I know, Sage were one investor, and while of course I don’t know all the details, I can potentially see the value to them and their OA program, in having a smaller outside bet on this horse, with not as much risk if you look at all the returns in a broader sense … but still as you note wages have to be paid, and costs are incurred.

I have no specific comment about Peer J (other than that I wish Peter Binfield well), but on the issue of “pivots,” I want to share an anecdote from several years ago when I was living in the Bay Area. A venture capitalist told me that his group had studied successful companies that had been funded by VCs and found that they had on average pivoted three times before getting the business model right. And that’s the successful ones. Let’s have patience with start-ups. Most don’t succeed because the effort is enormous. How many people reading this have successfully built a $10 million business? But dozens actively run companies that large or larger. Pivots are not divots.

I think we’re learning that Gold OA works financially in very particular circumstances — either when there are enough APCs paid in rapid succession so that the cash flows appear nearly as consistent as a subscription or annuity model, or when there is a large subscription business alongside to buffer the ups and downs of a smaller APC fetch. PeerJ doesn’t have either of these special circumstances, so it’s searching for an answer that doesn’t require either in order to work. It’s a tough nut to crack given the underlying financial dynamics of low-volume Gold OA publishing done in isolation.

We may also be seeing a general exhaustion of the market opportunity of Gold OA, especially as the major publishers have learned the ropes. They have succeeded in dominating the market dynamics in both of the special circumstances noted above. On a macro level, it seems that Gold OA needs a deep rethink, which is what Wellcome announced it is undertaking now (https://wellcome.ac.uk/news/wellcome-going-review-its-open-access-policy).

I have long had questions about the PeerJ business model. While they are transparent about their expenses, I have never gotten an answer to how much they are paid on average for a paper. The membership model was very interesting and still available to authors if that works for them. The emergence of a one-off APC was not surprising.

My question posed to Jason on Twitter was not meant to be rhetorical. I really want his opinion on what he thinks it means that authors flocked to PeerJ when they made it free for a month. And, I would love to know if those papers were of the same general quality they typically get. It would be interesting to know if these are new authors who never published with PeerJ before. Are these authors that typically pay for OA or were they authors that tried it for the first time because it was free?

I guess what I am saying is that this presents as an interesting case study and having some data about user behavior and motivations would be helpful to everyone trying to develop new business models. That said, I realize that PeerJ is under no obligation to share any of this information.

I agree that we are learning a lot from PeerJ, but one must dig past the breathless advertisements to understand what is really going on. PeerJ has offered special publication waiver programs over the last five years, so its difficult to estimate how much revenue is actually coming in. Even if everyone is paying full freight, it is still not a lot of revenue, given PeerJ’s scale.

With their new editorial model, they could be pivoting to be a more selective journal. However, putting in editorial effort only to reject papers just adds to their overall costs. It will also increase their submission-to-publication delays. In a few months, as this cohort of 1500 manuscripts moves through their system, we should see how many are eventually published.

It appears that market concentration might lead to self-cannibalization in the mega-journal sector: http://openscience.com/despite-divided-opinions-on-their-practices-and-prospects-open-access-mega-journals-command-significant-presence/.

Good piece and I agree with Kent that PeerJ’s situation points to the natural limits of Gold, but they have the choice of another pivot yet . . . To Freemium.