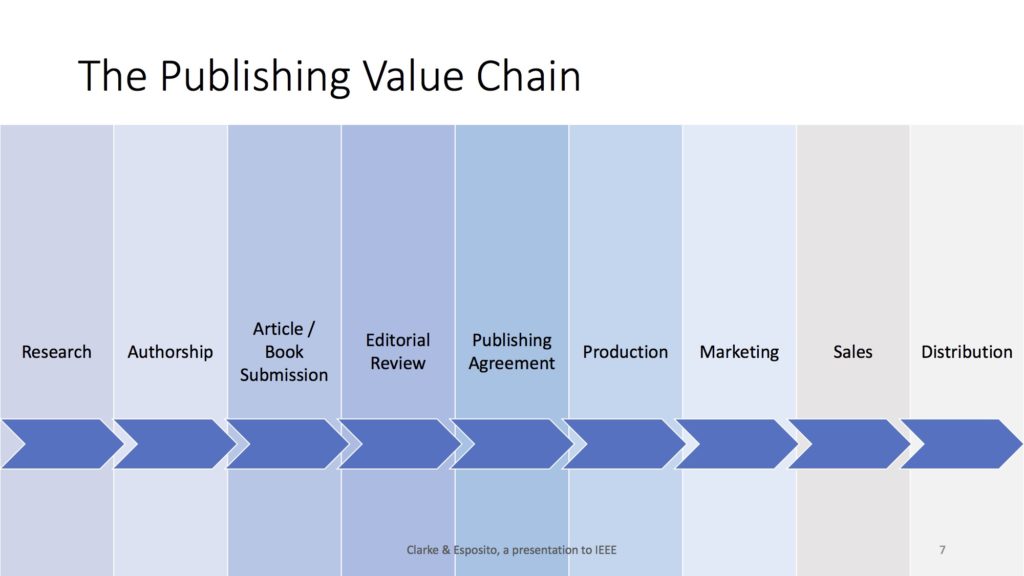

A value chain begins at the beginning and ends at the end, except when it doesn’t. The scholarly publishing value chain begins with research, moves to the act of writing, proceeds through manuscript submission, and then, if the publisher decides to take the project on, goes through a series of steps — production, marketing, sales, distribution — until the customer’s money is collected and is used to start the process all over again. That pretty much describes how it worked for the print world, and it held true for journals as well as books. When digital media came along, publishers attempted to re-create that value chain simply by inserting one format (digital) in favor of another (print). That worked to a considerable degree (what is often called the “crisis in scholarly communications” is in reality a cornucopia of intellectual riches), but it is now showing signs of breaking down. Where exactly is the end of the value chain, when published materials can have a life, or several, after the purchase? That purchase, in the traditional model, was supposed to be the end of the chain, when the last drop of economic value was wrung from the line of economic stages. But who extracts value when articles appear on ResearchGate, in institutional repositories, or Sci-Hub? Those are all downstream additions to the value chain, and they have come into existence because of the disruptive nature of digital media.

Perceptive readers will see the hand of Michael Porter in the background. That’s all well and good, but let’s keep it in the background, as the Porter opus is far more rigorous (and quantitative) than the high-level view I am summarizing here. What interests me about the value chain is the possibility that each step potentially presents different economic opportunities. Publishers historically have concentrated on what was (then) believed to be the last step, the purchase of the final document. But now, as many copies and versions of that document fly around the Web with impunity, and often earlier versions as well, the ability to monetize that presumed last step is being undercut. So publishers look elsewhere, and more and more they are heading upstream.

I began to think about this in preparation for delivering a presentation to the IEEE Library Advisory Board. I am inserting the slides for that presentation below. What became apparent to me was that publishers are hell-bent, or will be, on finding new ways to extract economic value even when the traditional method dissolves before their eyes. This in turn would require other elements of the publishing ecosystem (libraries, for example) to adapt as well. When publishers move upstream, where do libraries go to continue to create value for their constituencies?

Where can publishers make money upstream, and how? That is a challenging question because as you move further and further upstream, you move away from what publishers know how to do. Publishers are very good at making editorial judgments and at taking intellectual property and refining it for distribution, but those are, relatively speaking, downstream activities. On the other hand, all the way upstream you may have a scientist in a lab (or a historian crawling through an archive). How does a publisher monetize that? The scientist needs lab equipment — which publishers don’t sell; the historian may need knee pads and a face mask. Yes, I am being flippant here, but the point remains that the know-how of publishers derives from the place in the value chain that they have historically occupied.

This is part of the reason that we have seen so many upstream acquisitions over the past couple years. That scientist in her lab needs a way to collaborate with her colleagues, and she reaches to common collaboration tools like Facebook (yes, Facebook) and Slack, but she is also likely to be using Mendeley, now part of Elsevier. A thorough literature review is important as well, and she turns, perhaps, to Digital Science’s Dimensions. Or one step downstream she may draft an article and submit it to a publisher — which likely involves ScholarOne, now a unit of Clarivate, or Editorial Manager, recently acquired by Elsevier. Did that scientist draft that article in Microsoft Word, which until recently was the workflow tool as hard to get around as the Wall in Game of Thrones? Or perhaps she worked with Authorea, recently acquired by Wiley? Everywhere you turn you see workflow tools being gobbled up by major publishers. Only time will tell if this is an expression of fear, anxiety, compulsion, or strategy.

The reason to go upstream for a publisher is that it is like fleeing a burning house, as the monopoly nature of copyright downstream, where the chain historically was monetized, is undermined at every step. The problem, on the other hand, of going upstream is that it is not as easy to monetize those earlier links in the chain. (For smaller publishers the problem is simply that they cannot afford to.) Once upon a time, libraries would pay a sizable sum downstream for access to packages of content, but will they pay for a data analytics tool that examines submissions and rejections? If they won’t, who will? If the prospective customer is another publisher, is there not something awkward in Publisher A attempting to sell a tool to its rival, Publisher B? And how much is Publisher B willing to pay for such a tool? How will Publisher B in turn make money on that investment? Will B perhaps use the tool as a means to extract larger payments for enhanced content sold to libraries? But, wait! Libraries no longer need to purchase or lease content when it can be found lying around everywhere, from the hallowed halls of Ivy League repositories to the Russian steppe.

The promise, or prayer, of upstream activities falls into different categories:

- These various tools can be monetized in and of themselves. But the problem here is that at this time, the revenue from such workflow items appears to be modest.

- But cannot these tools generate new products, perhaps databases of information of interest to new classes of customers, now that academic librarians, in their furtive embrace of Alexandra Elbakyan*, have little or no need to pay for content? Surely if 23andMe can charge pharmaceutical companies millions for access to its database, Elsevier, Springer Nature, Wiley, et al., will find a way to create products that will command similar sums. Or maybe not.

- Or if all else fails, there is still the sale of content, but it is weaponized content now, reinforced by analytic and workflow tools that, like Shelob, ensnare the customer in a Web from which there is no escape.

In the perfect world dreamed of by publishers, all three of these revenue streams would become robust: sales for tools, sales for new databases derived from text and data mining (TDM) and usage analyses, and sales from content that is wrapped inside a comprehensive suite of tools and is thus uncancellable. The third strategy (lock-in of content by tools) is a defensive one and has the structural limitation that only organizations that already have very large content offerings can play this game meaningfully. The first strategy (new tools) will mostly be the province of start-ups, of which there is no small number; their likely path is to be acquired and folded into strategies two and three. It appears that many publishers are placing bets on strategy two, the generation of new products and services that are, as it were, metaservices that sit atop the traditional publishing paradigm. We are watching the beginnings of an emerging battle where the larger publishers will seek to look more and more like Clarivate, which already extracts great value without primary content offerings; and at the same time, Clarivate is likely to seek ways to undermine the content offerings of the largest publishers in order to diminish the effectiveness of their defensive lock-in strategy. It is noteworthy that all these scenarios tilt the playing field toward the very largest firms.

Sit back and have a beer. It will be a great game.

*It is a sign of the times that it no longer is necessary to provide a link to aid the reader in learning who Ms. Elbakyan is.

Discussion

16 Thoughts on "Upstreaming: The Migration of Economic Value in Scholarly Publishing"

Where can I find evidence that ‘These various tools can be monetized in and of themselves. But the problem here is that at this time, the revenue from such workflow items appears to be modest.’?

Papers App?

One data point: Digital Sciences’s 2016 revenue totaled less than €19 million. It is not clear whether this included all portfolio business revenue, and presumably it has grown since then. https://twitter.com/rschon/status/992463844177010689?s=19

Thanks Roger. However, we don’t know if Digital Science’s portfolio is representative for the tens/hundreds of tools and players out there in this respect, do we? Is there any (other) evidence for the statement?

Are you suggesting that the revenue from these tools might be approaching that which has come from traditional primary punishing? At a certain point it depends on definitions. Are citation databases and discovery services workflow tools? Certainly these have been monetized and collectively generate significant revenue.

I am not suggesting anything. Just trying to understand the statement (and looking for evidence): ‘These various tools can be monetized in and of themselves. But the problem here is that at this time, the revenue from such workflow items appears to be modest.’

Do we have any numbers on revenues? And what amounts are regarded ‘modest’?

A fine evaluation. As I write history, I’d like to offer, FWIW, an insight into that example, and this may help to explain the differences between that type of research and the STM fields with a view to things like open access and publishing.

By definition, history is old and truly new discoveries are rare, which is why they make the news. The 19th century saw a western European movement to transcribe and publish the (mostly Latin) content of medieval manuscripts and charters. This, and the occasional unpublished parchment manuscript, is what one consults when writing, for example, a history of the crusades or a biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine.

Copyright of these “upstream” works is in the public domain, but until Google Books, Abe Books and Archive.Org came along they could be consulted only in a few libraries. That meant costly travel to London, New York, Oxford, DC, the Vatican, wherever, where a scholar “camped out” for days or weeks while researching. No single library was likely to have every book you needed, and forget about photocopying. Reprints were rare (no print-on-demand), there were no central catalogues (think Worldcat.Org) and librarians could, in effect, play god (and some did).

The internet changed all that. Now researchers of history can focus more on the work than finding the primary sources they need.

Coming full circle, if a scholar specialized in my sub-field makes their research, already published in a pricey monograph or journal, available on Academia.Edu, I’ll be the last one to complain. I may even upload my dissertation eventually.

Stephanie’s comment has nothing to do with the post whatsoever. Why place it here? What axe is there to grind?

I believe she was looking at your subject as the future of publishing, the same as Michael was below, which you answered much more politely as “The real answer to your question, though, is that that is not what I was writing about. I was describing how publishers are responding to the changing environment.”

Joe, I can already anticipate your response to what I’m about to write, but am writing it anyway, as it seems important to register an alternative version of this future which you hint at but do not fully articulate: that is a future where the community (and by community, I mean researchers, students, librarians, and technologists) develop and sustain work-flows and platforms that allow for publishing to take place (and in which there is a place for traditional publishing functions of selecting, editing, promoting, distributing) without so much of the money in the system being siphoned off to shareholders and profit-sharing amongst employees. You are hinting at this but don’t come right out and say it. Or am I misreading this?

Hi, Michael – there are indeed many signs of fevered activity in just such spaces, although little sign of real focussed attention at forging these into something more powerful than a sum of parts. These activities could potentially, if strategically driven or very lucky, coalesce to create some or all of Joe’s three scenarios. Libraries/universities and some funders have also got long experience of content creation/management and researcher engagement to draw upon even if their intention is not often to monetise these activities. That could potentially change as universities come under increasing financial pressure, and if supported by faculty and funders, and possibly if enabled by creative partnerships with third parties. Very exciting times!

Thanks for a clear and thoughtful read, Joe!

Michael Roy: Why don’t you tell me what response you anticipated?

Joe, I have sensed over the years in reading your articles and comments that you don’t have a great deal of confidence in non-market based approaches to scholarly publishing, and that the commercial publishers succeed because they have the capital to invest in infrastructure and systems, whereas the open access/open source crowd is not particularly well organized or capitalized.

Your comment is more what you will hear from commercial publishers, who don’t believe the not-for-profit sector capable of accomplishing much. I think that is arrogant. The real answer to your question, though, is that that is not what I was writing about. I was describing how publishers are responding to the changing environment. I was not creating a comprehensive vision for the entire world of scholarly publishing. I would add that if you are going to realize the vision that you espouse, the place to begin is to hire the very best managers. People make the difference. This is something the commercial sector understands very well, but it is routinely ignored or dismissed in the not-for-profit world, where the number of superior managers is small. A very good manager is worth 100 times what a merely good one is. Pay the price, get the advantage. In all things talent wins out.

I’ve got to agree with Alicia. I’m trying to start a scholar-run journal with some colleagues and getting a working workflow based entirely on free community based open source projects is -hard-. PKP’s OJS is fantastic and about as difficult to install as wordpress. But it’s still clearly a work in progress.

So even though you can take papers through peer review, things get hard in production. Texture, for example, is just not fit-for-purpose. Instead of following Pubmed’s standard (NISO JATS 1.1), they went and made up their own version (DAR) that’s a little different.

But back to before article submission – Zotero can replace Endnote and Inkscape/GIMP can do a lot that Illustrator/Photoshop can do, but good luck trying to find a user-friendly free open source alternative to GraphPad Prism. JASP is making some headway to replacing SPSS for basic statistics, but isn’t there yet.

News from earlier today would seem to serve as another example:

https://news.sky.com/story/ftse-giant-relx-plots-100m-bid-for-times-higher-education-11564527