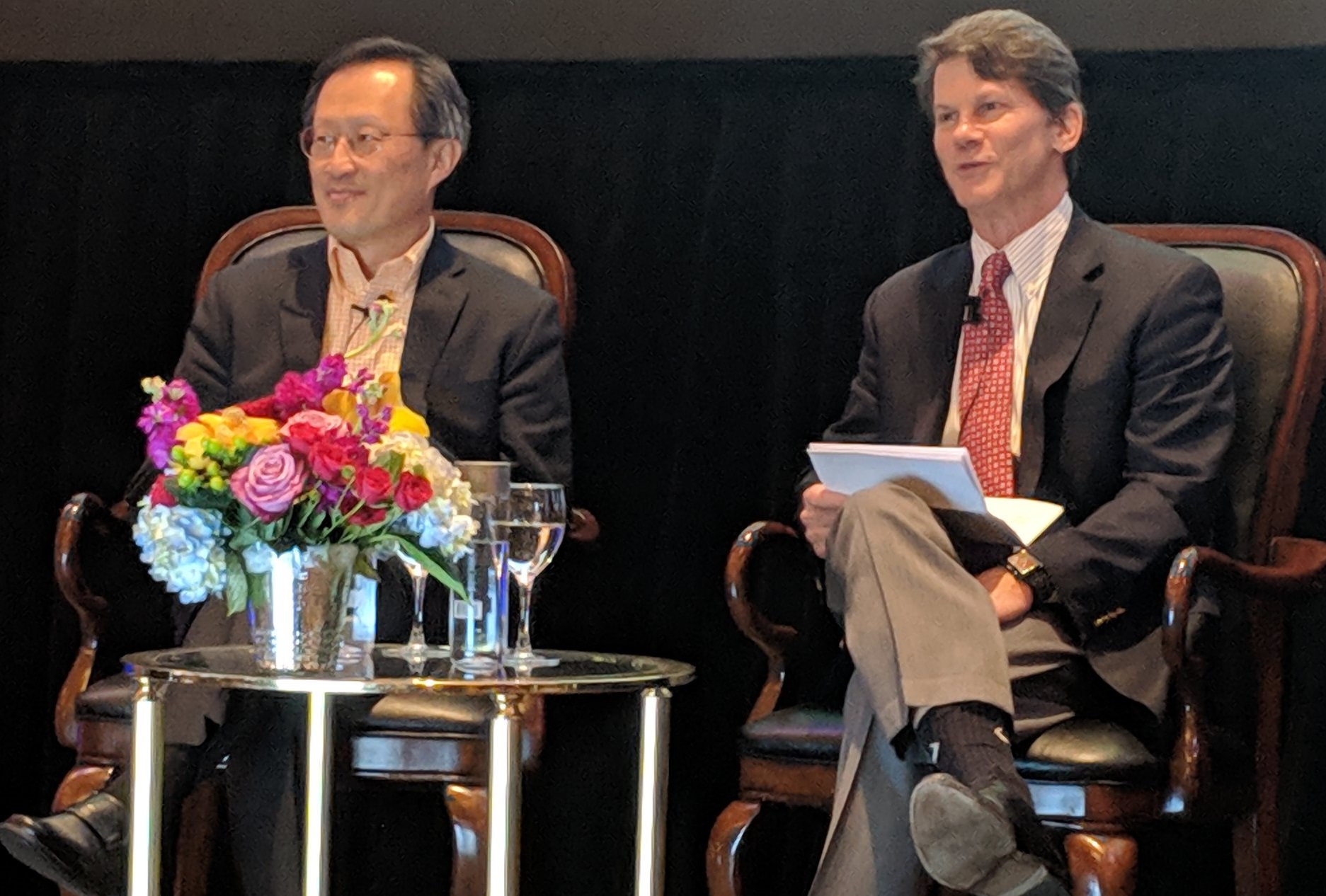

Last week, approximately 180 leaders from scholarly societies, libraries, publishers, and other organizations came together at ITHAKA’s Next Wave conference in New York City. The day’s sessions featured an array of different formats and experts, focusing mostly on fundamental changes facing higher education in the United States, the result of underlying demographics, financial pressures, narrowing political support, and tension around how to define student success. The program also included a number of sessions focused on scholarly publishing and academic libraries. The opening session was an interview, conducted by ITHAKA president Kevin Guthrie of Elsevier’s chairman Youngsuk (“YS”) Chi, with some additional questions from the audience. The interview generated discussion and perspective not only about Elsevier itself, but also about broader changes in scholarly communication and approaches to organizational leadership. I have attempted to reconstruct the interview here from my notes, and Chi and Guthrie have each had a chance to edit and expand their remarks here for the record.

Guthrie: More and more, people question the motives of large companies like Google, Facebook, and in our environment, Elsevier. As a leader of one of those companies, how do you square the commercial goal of profit maximization with the pursuit of public purposes?

Chi: You have to balance the two or you cannot persist. Sometimes it is a matter of timeline. It is true that shareholders demand short term returns. But corporate leaders must ensure longer term perspective. We have tried to address this partially by declaring that we have to serve scholars and sometimes that will mean taking a longer view. We have asked shareholders to be on a journey with us, saying, “if you want only short term returns, please do not own our shares.”

We have short, medium, & long term investments. For example, about 15 years ago, we debated whether to maximize market share in journal articles published. We decided to sacrifice some market share while raising the quality of our portfolio (as measured by field weighted citations). It was the right strategy.

There are several key questions for us as we evolve strategically with our environment:

- What is the source and allocation of our resources? We have to think about a different flow.

- Which technology should we embrace and let go?

- What is the long-term impact of poor decisions, such as not investing enough in research?

- How do we manage talent?

I have an analogy I like to use to explain the direction we are taking. Elsevier had originally been farmers — in the print environment, we would produce journals and “harvest” without having any means to know how our products were used in any detail. Digital distribution enabled us to begin to offer a supermarket for the things we farmed, in which we could have direct relationships with our library and research customers. We began to get to know and create a closer relationship with shoppers resulting in increasing interest and opportunity on our part to help them “cook.” Now increasingly we have a restaurant — we have recipes, we work directly with the chefs to cook the food ourselves, and we can serve the meal to help enhance the efficacy of the researchers.

Guthrie: Let’s bring your farm and restaurant metaphor to the scholarly context: Elsevier has recently acquired a number of workflow and preprint tools, for example, SSRN, bepress, and Pure. Is that about providing value? — some might argue that it is about creating lock-in.

Chi: Actually, it is that we don’t want to become irrelevant. If the conversation disperses from journals to somewhere else, we don’t want to lose engagement with the researchers having a dialogue about scholarship. We don’t see it as creating lock-in. It is about staying involved. There is no way to lock-in curiosity.

Guthrie: Why shouldn’t we worry if you have the restaurant, the supermarket, the farm — all those parts in vertical integration? Why is that good for the sector?

Chi: We are not a platform company with a near monopoly like Google or Facebook. We are part of a vibrant ecosystem. In the short term there is no real threat of any of the major publishers having a large enough market share to be a concern. Elsevier only has 17% of the journals published in English.

Putting that aside, it is important and valuable that some larger companies are serving the sector. Some of the things we are trying to do are very costly. We have to be prepared to invest when others are unable or unwilling to do so. It takes resources. And then of course there are other risks that start-ups can take that we cannot; they might discover new opportunities that we were unable to see. When those seem particularly valuable we could acquire them sometimes.

Guthrie: It seems to me that transparency is incredibly important for you. Journals are not substitutable, so mini-monopolies can emerge. You may have only 17% market share overall, but individual journals can have high market share in specific fields and disciplines.

Chi: That is true, but in the medium and long term, every field and discipline is up for intense competition; the types of mini-monopolies do not last automatically due to one’s size.

Guthrie: Elsevier is positioning itself not as a publisher but increasingly as an analytics company. That is a huge change in direction for a large company. Many in our audience lead libraries and publishers: can you share with us lessons you have learned leading change in an organization under these circumstances? What advice can you offer for those in similar positions in publishers and libraries?

Chi: When we began the process of reassessing our business and strategy, we took three major steps.

- We asked ourselves, “What do we want to be when we grow up?” That internal debate was robust and sometimes even rather violent! We needed to come to a strategic decision.

- Then, we needed to determine if we had enough resources to pursue the chosen direction and we needed to begin to allocate those resources.

- Finally, we needed cultural change. In many ways that is the hardest part. We needed our employees to believe that taking risks was encouraged. We previously rewarded predictability. Now we needed ideas to come from our employees who are closest to the customers, bottom up. Our employees must not think they will be punished for being wrong. That took a serious commitment from senior leadership and we had to back our words with our actions. We emphasized that it was better to learn from small mistakes than big ones. I think we have been able to change the mindset for much of the company so that people are more willing to take risks and accept that we want to fail often and fail early, so that the cost of each failure can be small.

Guthrie: How far along are you in the transformation of the organization from a financial perspective? What percentage of the business has shifted to data analytics? Is part of the strategy about protecting against loss of revenue from open access (OA)?

Chi: Our strategy is not really pinned to OA. Our strategy is about growth. Having said that, in the research domain, probably a good two digit percentage of our revenue comes from non-publishing revenue. In the health sector, however, it’s a very large percentage.

All this said, let me make it clear that we are not ever going to take our hands off the content curation. Having the content in a structured and curated way is very important to the analytics business.

Guthrie: In the shift to analytics, an area of growing concern is privacy. How are you planning to lead in the areas of privacy and data management?

Chi: Most of the data we have at Elsevier are not B2C but in the B2B sector, so we are less concerned about this, although in the health sector we are very conscious of HIPAA. I do think that this is an important issue though. I believe that major companies need to establish a new kind of ‘CEO’, a “Chief Ethics Officer”. With the change going on and its unforeseen implications, companies need people focused on ethical implications and best practices.

Then we moved to audience questions.

Chuck O’Bryan from SUNY Libraries Consortium: We manage collections budget from a deficit perspective. What is Elsevier’s approach internally to allowing us to manage our costs?

Chi: Our ideal endpoint and aspirational goal is that everything should be available to everyone. From there, we think about prioritization. As a librarian, you know what is most critical to your users. We make similar decisions about which ones are most important from our perspective, based in part on your usage.

But more broadly, it shouldn’t be a zero-sum game for universities, with flat library budgets.

We are investing in so many ways. For example, we are bringing machine learning to create excerpts/snippets rather than having authors write them. We want to continue to bring more value for the same price to our customers. Also, we will make more content open — such as flat content — but if you want more functionality and efficiency you can pay for what you value. So we want to increase the value of what you receive and expect that institutions will find the resources for valuable content and services that deliver a return.

But we are not just focused on value, we do what we can to remain affordable. Our cost increases since 2004/2005 has been in the lowest decile of publishers. We will continue to commit to that.

Guthrie: I want to challenge this a little bit; the questioner asked about the mindset of your colleagues on this side of the negotiating table. Is it a profit maximizing mentality, where the goal is to extract as much money as you can from the negotiation?

Chi: No. It’s about getting the most out of the relationship over the longer term, not just from a single sale.

Guthrie: It’s great to add more value, but libraries only have so much money. It is important for Elsevier and other STM publishers to recognize that there is a crowding out effect, especially for the humanities and some social sciences. When prices go up for very large contracts, there is less money available for those other kinds of content. From a practical perspective, there is some zero-sum here.

Chi: I recognize universities are reducing the share of their funds going to these purposes. We need to convince university leaders that there is value here that they should be funding, so that researchers and research management can be more efficient.

When Elsevier first embarked on this strategy to address the evolving needs of researchers, we had to work directly with the faculty — which to some people seemed like we were going around libraries — but there has been a huge reframing of libraries over the past 15 years as being about more than just collections. That has given us the opportunity to work on these issues in partnership with libraries in ways that were not possible previously.

Cathy Wilt, PALCI: What would it take to have Elsevier entirely open in the US through a national license?

Chi: It’s a question of resolve and how difficult it is to assemble so many organizations together. The United States is the most challenging and complicated market from a national licensing perspective.

Yuri Lazebnik, scite: Elsevier’s profit margin is higher than Apple or Google. Are you making too much off the deals with libraries?

Chi: RELX’s true *profit* is in the teens, but we do not report our profit for each division in our public reporting. The figure you are referring to is the operating margin, which we report at the division level for Elsevier. The operating margin excludes many important costs such as cost of capital, taxes, and amortization, all of which are expensed only at the level of our parent company, RELX. So evaluating Elsevier’s operating margin conveys an inflated sense of Elsevier’s profitability.

Joseph Esposito, Clarke and Esposito: Which competitors do you focus on when you think about who is doing the most interesting things?

Chi: Of course we pay attention to Springer Nature, Clarivate, and other major players. But those are not the ones we fear. It is those we don’t know, who are nimble and hungry and creative and will be acquired. I fear those I don’t know about. It’s quite easy to start a new company to solve difficult and important problems with six people in a garage. I wish some of it happened on campuses, in libraries, and I don’t know how much of that is going on.

George Fowler from Old Dominion University: Can you give examples of activities that Elsevier is doing that may not be profitable but are for the public good?

Chi: We were the first to support Portico, we support CLOCKSS, and other preservation initiatives. We acquired Mendeley at significant expense and de-monetized it completely. Our SSRN acquisition. We’re not doing these things for the bottom line only; we’re doing them because it keeps us relevant in the conversations going on among researchers. Does that have a long-term financial benefit? We hope so, but in making these investments we are emphasizing the value of our services for the researchers and supporting the new kinds of work they do, which to my mind is for the public good, not primarily revenue and profits.

Cappy Hill from Ithaka S+R: To what extent is your business contingent on the tenure system?

Chi: It is not contingent on tenure directly. But — our business is absolutely contingent on the competition among researchers and the assessment of their research. I am a huge anti-ranking person when the methods are a zero-sum game, that is well known. But we have to have a system that has hefty competition among researchers in order for there to be great research. And in that environment Elsevier can thrive by publishing high quality curated content, tools that support researchers’ work, and tools for assessing the quality of the work.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "Elsevier Chairman YS Chi: An Interview"

“It is those we don’t know, who are nimble and hungry and creative and will be acquired.”

That is the most sinister thing I have ever heard.

Resistance is futile.

You will be assimilated.

Sinister, unless it’s your start-up, and you’re cashing in on all your hard work. I would think that the founders of Mendeley, SSRN, bepress, Aries, etc. would all beg to differ with your interpretation.

I actually read that statement quite differently. He feared nimble, hungry, creative startups that would be acquired by competitors. That makes sense because after acquisition the nimble hungry startup would have access to greater resources.

Craig: I have to disagree. Your statement in my mind is analogous to not driving defensively which is what Chi is proposing. You seem to forget that competition is a fierce reality. I think what Chi was referring to is that one has to be aware of small startups like Amazon was and if they present a synergistic opportunity to offer to buy them. There is no mandate that the offer has to be accepted!