The announcement that Bertelsmann, the parent of Penguin Random House (PRH), has joined the hunt for Simon & Schuster (S&S) provides a good opportunity to describe that new breed of company, the 360° competitor. In the publishing world the principal entity in this category is Amazon; in STM publishing, the closest to this paradigm is Elsevier, though Elsevier has yet to recast its strategy in this direction. (Of course, there is always the possibility that ResearchGate will sneak into this coveted position under the noses of its growing number of publishing partners.) A 360° company is one whose strategy looks and reaches in all directions; unlike, say, Apple, it is not committed to totalitarian control of a walled garden or ecosystem. And while size and market dominance are a precondition of the 360° company, they are, as it were, merely the cost of admission, as the defining aspect of such an organization is that it operates as an industry nexus, where all participants, friends and rivals alike, are likely to pass through. Not all companies can aspire to such a strategy and, indeed, many companies do very well by coming to terms with the nexus. An outstanding example of this is Netflix, which operates on the Amazon Web Services cloud platform even as it competes with Amazon in video streaming. Another candidate for 360° status is Ingram, which runs much of the back office of the book publishing industry behind the scenes, but Ingram itself is bounded by Amazon, which takes an unsentimental view of its partners.

A bit of background. PRH, which was forged in a merger, is by far the world’s largest trade publisher, with global sales of about $4.3 billion, half of which derives from the U.S. The second and third largest trade publishers are HarperCollins (which has also expressed interest in S&S) and S&S itself, but PRH is bigger than those two companies combined. The sale of S&S has been bruited about for years, but now its newly merged parent, ViacomCBS, is formally shopping the company. I wrote about this previously (see item #13). It seems likely that S&S is now being sold for the simple purpose of tidying up the ViacomCBS operations as a prelude to a sale of ViacomCBS itself to a more dominant streaming media company (Netflix, Amazon, Google, Disney, AT&T/HBO, et al). No, the big cannot get big enough, and this is true in publishing as well as other media. Note how many times the word “merger” appears in this paragraph.

But if ViacomCBS is a seller, why is Bertelsmann a buyer? S&S is nonstrategic to a streaming media company (whatever value is put on a bid for ViacomCBS, it will not be one dollar higher because ViacomCBS owns a no-growth publisher, so better to sell it separately and make a few extra bucks). Bertelsmann, on the other hand, is operating in a different industry, where it can squeeze out higher profits on flat, or even declining, sales. The primary reason for Bertelsmann in doing a deal like this is to fend off Amazon, but the benefits go beyond that. PRH/S&S would be able to put pressure on all downstream market participants (Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Ingram), thereby shoring up its margins. Furthermore, as the Bertelsmann CEO notes, the sheer presence of the Amazon behemoth in the book business makes it unlikely that an acquisition of S&S will be stopped on anti-trust grounds.

With S&S as part of its operations, PRH would then turn its attention upstream with renewed vigor. Authors and agents will not be happy about further consolidation in the industry, as it will lower advances and put downward pressure on royalties; it will also add to the many “non-negotiable” aspects of a publishing contract such as the disposition of subsidiary rights and the ability of authors to revert rights after a period of time. It is a remarkable fact that publishers have succeeded over the past two decades in reaping 100% of the efficiencies from digital media and workflows and shared none of that with authors. This will continue. More authors will find their way to smaller publishers and will be forced to forego the market reach of the largest companies, not to mention the once-lavish advances. Many authors will migrate to self-publishing, which is the key growth area in the industry, but they will make less money than formerly with major commercial houses.

After pressing forward downstream and upstream, the new 360° company will look to the left and right, with an eye toward unbundling its platform. “Platform” in this instance is a metaphor for the complete set of capabilities under a company’s control. It is axiomatic in the publishing industry that you can unbundle everything except for editorial. PRH, for example, already owns a large and growing distribution business, putting it into direct competition with Ingram, its downstream partner. If and when S&S is added to the portfolio, the scooping up of even more distribution clients is just a matter of time. Such clients gain access to the PRH operations, which are among the best in the world, and may even opt for inclusion with the PRH sales offerings, instantly giving even a small publisher unsurpassed retail distribution. Over time, other capabilities will be offered a la carte, perhaps demand-creation marketing, putting PRH into competition with industry upstart Open Road Integrated Media and its Ignition platform (in some respects Open Road is evolving into a copyright-compliant version of ResearchGate for trade books), or such things as metadata management and social media marketing. At every node in the network, PRH will exact a toll. As the platform’s unbundling continues, more and more of PRH’s revenue will derive from what is not, strictly speaking, publishing, but the broad suite of services that enable publishing. Some companies will participate with both feet, selling themselves off to PRH; others will opt for a service or two, drawing on PRH’s clout and scale when it suits them, but remaining independent for other services (always including editorial). The gain for PRH in this is that it can now tap into 10%, 25%, 50%, or even more of the overall industry, rather than being stuck with the high-risk and capital-intensive operations of its proprietary publishing. It’s worth remembering that the global book business has revenue of around $150 billion.

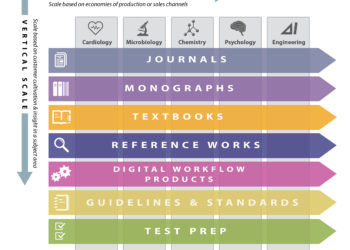

The strategy for the 360° competitor is akin to that of the network model of publishing, but the differences are crucial. In the network model (which I advocate to anyone who will listen to me), a publisher adds new media types and links them together in various ways. A traditional journal publisher, for example, adds an open access service, and then moves into books, databases, conferences, conference proceedings, webinars, podcasts, and any media type that will find an audience. The common glue of all these media types and formats is the usage data, which informs each node on the network. The 360° organization, however, goes beyond this, adding operations that it does not necessarily control and also nodes that prohibit pan-network data-sharing. Atypon, for example, though a unit of Wiley, segregates its clients’ data from that available from Wiley’s proprietary publications. If Wiley aims to become a fully 360° company, it will have to add many more infrastructural services like Atypon.

To become a 360° company, at a minimum a company must have the following characteristics:

- Scale. Only a company with a dominant position in its market need apply. Smaller companies that pursue this model will end up getting acquired and broken up for parts.

- A nuanced view of the place of editorial in an organization. No business person should ever interfere with editorial decision-making, but even publishing companies are not purely editorial in nature (see this argument). As new operations are added to the 360° competitor, fewer and fewer of them are likely to be editorially based. For example, think of Elsevier’s acquisition of Mendeley or Wiley’s purchase of Authorea, which, despite its name, does not make editorial judgments.

- An appetite (and capability) to acquire other services. Scale is typically required for this, but there is also the psychology of acquisitions to take into account, where a management team is comfortable working with assets that were not invented here.

- A willingness to unbundle the platform. It is one thing to acquire a service (like SSRN or Atypon) that already has third-party clients, quite another to take proprietary infrastructure and make it available to third parties.

It is an apparent reluctance to unbundle its platform aggressively that has stood in Elsevier’s way toward full 360° status. That could change, however, if the company’s plunge into data analytics fails to have the promised payoff. Or even if data analytics proves to be wholly successful (adding revenue even as it serves to lock in content — that is, publishing — revenue from existing customers), an unbundling strategy could unlock more revenue and higher margins. Elsevier’s position is much more complex than PRH/S&S’s would be, as PRH only has to worry about Amazon (did I say “only”?), whereas Elsevier has to wrestle with a market that is not purely commercial (e.g., the many not-for-profit participants, the role of third-party funders, the policies of some governments). Now that the metaphor of pure content aggregation (the Big Deal) has run its course, academic and professional publishing is seeking a new metaphor, and the 360° competitor just may be it. Keep an eye on Amazon and PRH for their next iterations.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "The 360° Competitor"

The conclusions here leave me feeling that the machinations started by Robert Maxwell from the 1970s (via Pergamon Press) in STEM publishing have not reached their zenith! Maxwell realized that brilliant scientists could be brought to serve journals for nothing but a bit of recognition, and then every government (via Universities) would need to pay whatever was asked. Mergers, as noted by Joseph Esposito for book publishers, kept costs down, increased demand from the taxpayer who paid both authors and for access to read, and improved the monopoly on distribution (as with the book publishers above). About year 2000, Open Access and the internet looked set to destroy the model overnight, but it turned out the nobody could replicate the combination of quality control (review and redactory services) and distribution, for any less money than the commercial STEM mega-publishers. Both the authors (recognition again) and the business models of the funding agents turned out to want to pay as much as ever to publish their work to not compromize distribution. The author’s 360 degree concept certainly seems the likely direction for the big STEM publishers, with added value around the published manuscripts that grant-bodies will continue to want to pay for handsomely.

Very little of the $150 billion global book industry is paid for by governments. This argument is a red herring.

Just to note, however, that this trend is actively resisted, by academics [some of whole DIY publish], small publishers, librarians, and OA database curators with thousands of journals, like SciELO and Redalyc (and smaller ones offering Small Deals – eg OLH, freejournals.org). These moves are highly politicised battles for the soul, and control, or academic publishing. Market forces in publishing leading us towards 360 degree companies need to be recognised for what they are – profit-driven. Not driven by ethical behavior or a justice mission [unless those pay]. Any efficiencies or better services gained by merging and buying out, need to be balanced against these concerns. Resistance is also enabled in a small way by universities signing up to DORA, because articles and other outputs published in less mainstream outlets should be recognised on merit, not place of publication in hiring and promotion decisions. My university just signed.

[I have been staying off these debates during lockdown, but we clearly need to redouble our efforts if new corporate maneuvers are beginning]

I agree about the “book industry”. However, your blog appeared in “Scholarly” kitchen, and the last paragraphs of your piece, that I write about, are about “scholarly” publishing. Scholarly publishing is virtually all paid for by governments/taxpayers (directly or indirectly via Universities, Research ministries etc) with a smallish proportion (mostly biomedical) by not-for-profits.