Editor’s Note: Last month’s post making the argument against paying peer reviewers sparked a lot of commentary, both on the post itself and throughout the various academic outlets on the internet. With the theme of Peer Review Week 2021 just announced, peer review has been front and center on our minds. Which seemed like a good time to revisit Jasmine Wallace’s excellent primer on reviewer best practices for the peer review process.

In my experience, the streamlined process of peer review is complicated when reviewers with good intentions do bad things. A reviewer who does bad things displays behaviors that slow down or lessen the effectiveness of peer review. A good peer reviewer displays efficient behaviors and adds value to the process. The good thing about a reviewer who does bad things is that they can change. There are quite a few ways to shift bad behaviors and habits of reviewers to become not just good, but great peer reviewers.

Mind the Time

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Seriously, good reviewers do not keep a fellow peer waiting longer than needed to receive their review. Keep in mind that your review is holding their work from progressing. Some people have been working for years to get their research “peer review” ready. Their blood, sweat, and tears have gone into the work you’ve been asked to evaluate.

When you get the initial invitation to review, make note of the deadline. Pull out your calendar and check to see if you can realistically return a fair and sound assessment of the work in the allotted time. If the deadline is not reasonable, don’t be afraid to ask for an extension.

In fact, the perfect time to ask for an extension is immediately after you receive that initial invitation. All journals have an internal turnaround time deadline which is designed to incorporate delays. So ask for an additional week if needed. Or, better yet, if you know when you’re able to return the review, put that information in your reply to the invitation. Remember: a good reviewer requests an extension (if needed!) prior to the deadline.

Here’s another great habit to help you develop into a good reviewer: read the notifications. We understand that these notifications might be annoying, but they are there to help keep you on track. We know you’re often swamped, and don’t intend to be late, but if you don’t reply to our status inquiries then we are not aware of your current needs. If after reading the abstract, you’re just not interested in reviewing the paper, then hit the decline button. Respond and don’t delay, every day passed is another day the author is kept waiting.

Be Intentional

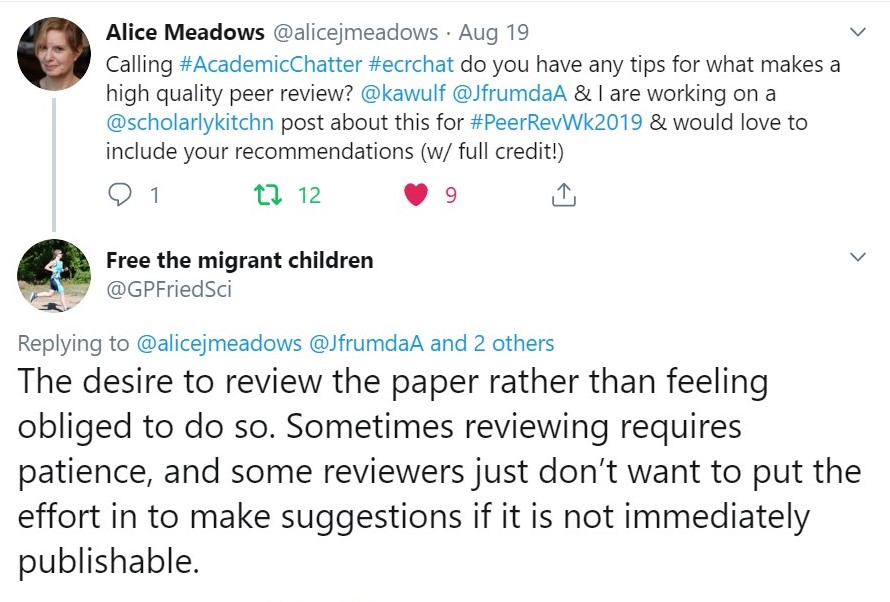

Reviewing is a voluntary task, and a good peer reviewer approaches the job with intentionality. At times, the voluntary job will require more work than you expect. Go into the peer review process with a willing attitude and a desire to truly make the work better. In fact, when we asked the community what makes for a high-quality peer review, the first response was that the reviewers should approach the review with “a desire to review.”

Good reviewers really take their time to provide a valuable evaluation of the work, even if the content is not ready to be published. There is a strong focus on novelty in peer review, which is completely understandable in a world where there is an overabundance of contributors. However, make sure your feedback is helping to make the work better. If you’ve accepted the review, then honor the researcher and the research by adding value to what is given to you.

It is not your job to copyedit, but to evaluate the research for aspects such as originality, appropriateness, and relevance. Do not worry about the formatting, and read beyond language barriers. If you notice that these issues are preventing the science from being understood, then let the author know and request that the paper is allowed to be resubmitted when those problems are addressed.

Keep in mind that good content for all researchers is what we need more of for the greater community. The more research that is published, the more content contributors are reading and disseminating. This helps to diversify the areas and reach of the scholarly community-at-large.

Read the Guidelines and Scope

Not reading the reviewer guidelines definitely constitutes a habit of a reviewer who does bad things. If you’ve never read the reviewer guidelines, be it your 1st or 41st review, please do so today. These instructions were made to guide you on how to provide the best, most useful review possible. It took a team of people weeks, if not months, of carefully considering the best ways to help you succeed. Take the time to review those resources. This can be particularly important in the age of megajournals, which review for accuracy but not novelty. Try not be the reviewer who gets very angry when their rejection suggestions are dismissed by the editor because they are based on novelty for a journal like PLOS ONE. Know the policies of the journal you’re reviewing for and avoid that frustration.

You may find that certain organizations do not have reviewer guidelines. Or, it may be that the instructions are nearly impossible to find on their website, but you should always ask for guidelines if they are not made readily available. Perhaps this is your opportunity to add value for the author(s) in a way you didn’t consider. You need clear instructions so you know what is expected for your review, especially if you’re a first-timer.

And be aware of the mission of the organization for which you’re reviewing. You want to ensure that the research you’re asked to review is aligned with their organizational values. And you will provide more intentional feedback when you know and buy into the mission of the organization. You should also be clear about the scope of the journal. This often gets updated every few years to include emerging research areas, so read it at least once a year.

Educate and Grow Your Community

The primary purpose of the peer review process is to fairly provide feedback, or information on, your particular field. Keep that at the heart of your review. This is all about peer mentoring.

The ultimate goal is to strengthen your community of researchers. Ask yourself, “How does my review make my community stronger?” This is especially true in smaller, more niche fields of study. Reviewers in these types of communities should work even harder to strengthen their small group. Sometimes the smallest communities are the strongest, and larger communities can learn from them how to continue to grow and thrive.

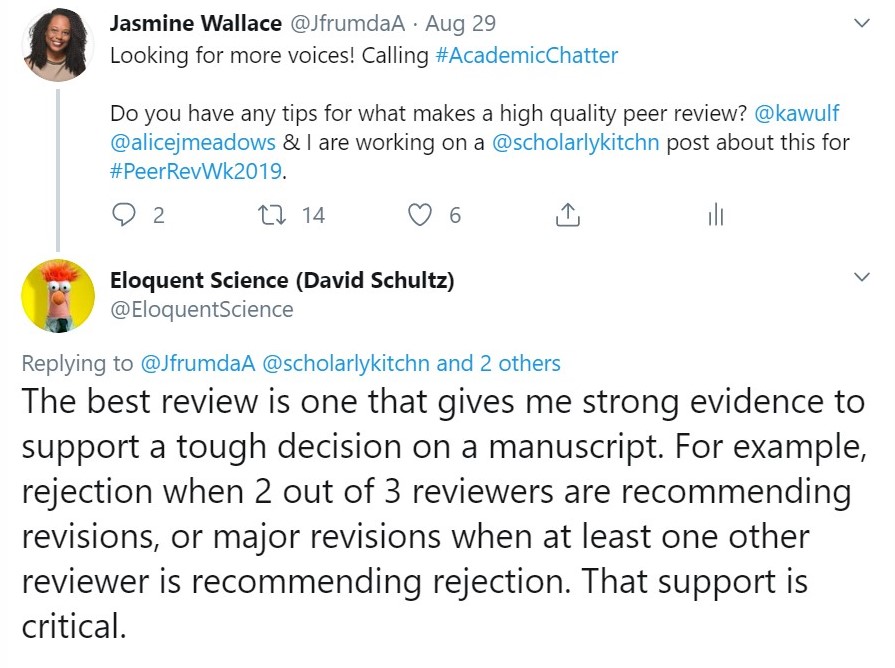

It may be difficult to see how some work helps to strengthen the community, and all you can think to do is reject the work. And that’s okay because, as @EloquentScience says, at times, “the best review is one that gives me strong evidence to support a tough decision on a manuscript.” Rejections also help to change the field if done well, because constructive feedback has been proven to be an effective way to improve research. Remember that the journal is soliciting your review precisely for your expert feedback. One major goal of your feedback in peer review is to help your fellow peers improve, which helps to promote a culture of growth and learning.

Be sure that your review is detailed and specific. You agreed to review this paper, so take time to make sure that your review is helping to educate. Do not write a few simple statements filled with your opinions, rather make sure your feedback is robust and informative. If you know additional research will make the work better, tell them where to start to look for that research. Make sure that your feedback is corrective so that you are adding value to your larger community one review at a time.

Say No (and recommend others)

Stop agreeing to reviews that you really cannot or do not want to handle. Feel free to say ‘No’ to the initial invitation. Keep in mind that, if your review is truly needed, then you will know upfront; otherwise, your occasional ‘No’ is okay and not frowned upon. You should not turn down almost every invitation you receive, but if you truly know you don’t have the time to do the review, then don’t.

When you are asked to review, the inviter may not be aware that you are working on the final stages of your own research. Or that you recently agreed to spearhead a new clinical trial. Or simply that you just accepted two other invitations right before you received their invitation. Do not overburden yourself, remember that the goal of your review is to provide useful feedback and you are less likely to do that if you’re tired or overworked.

And if you can’t do the review yourself, recommend another colleague who might be able to. When thinking about ways to be more inclusive, recommendations are an excellent way to help support newer reviewers. Think about your ‘No’ as an opportunity to include these new reviewers in the often closed reviewer pool. Recommendations are usually the way new reviewers are discovered. The validation you provide might just be what helps to reshape the system of reviewer selection.

Saying ‘no’ is also great opportunity to help train your students and postdocs as peer reviewers. If you can’t do the review yourself but have a student or postdoc you think could do the manuscript justice, then by all means suggest them to the editor. In my experience, students and postdocs are capable of doing excellent and thorough reviews, and as a mentor, you can oversee the process and help them learn to be contributing members of the community. Just be sure to run this through the journal editor — send along the contact information of the person you’re recommending and let the editor take it from there, rather than accepting and having someone else in your research group do the actual review.

Sometimes you want to handle the review but can’t do it when you’re asked. Feel free to say no, but also let us know when you can do it. We are willing to work with willing reviewers. When you want to handle a review, we know that means you really want to add useful and valuable feedback. Again, these types of problems were considered beforehand and we understand, just let us know.

Be Bold and Constructive

One concern I’ve heard from reviewers is not wanting to provide constructive feedback when the authors of the work are their superiors. Be bold and constructive with your feedback. Peer review is about peer-to-peer assessment, which means that in the game of peer review, every player should be seen as a peer — someone who’s on an equal playing field with you. An author’s credentials should not be the reason you don’t suggest that work needs to be made better. Do not back down on your opinions if they are going to make the work better, experts need corrective feedback just as much as early career researchers. In fact, they likely know better than anyone how a good rejection makes your research stronger.

Please don’t give any feedback you would not want to receive. Do not make dogmatic, dismissive, or blatantly rude statements about the research. Not only is this type of feedback unprofessional, but it’s also useless in the attempt to make the research better and stronger. Again, even if the paper should be rejected try to give corrective feedback that adds value.

The peer-review process has been widely criticized for perceived bias by editors and/or reviewers. Therefore, be bold and opt-in if you’re ever presented with the opportunity to participate in open peer review, or other new peer-review workflow models. Open review is designed to increase transparency in peer review and give power back to the community by opening up an otherwise closed process. With this particular model a reviewer can choose to identify themselves by signing their reviews. In addition to making sure reviewers are given credit for their work, open peer review can help reduce and diminish those negative critiques about the peer review process. In some ways it’s bringing back the heart of peer to peer review.

Get Credit

Peer review is thought of by many as an academic duty. Others see it as a way to keep up-to-date with the latest developments in their field, or, to be active members of their community. Duty or not, good reviewers make sure to get credit for their work! Reviewing is a volunteer job, which requires a considerable amount of time and effort to perform. And, while you may not typically get paid to do it, there are a few other ways that you can be acknowledged for your contribution.

One quick and easy way to ensure you get credit for your research contributions is to sign up for a Publons account. Publons is a free platform powered by Web of Science. It was built to help reviewers keep track of their reviews, verify that they are the ones that performed the review and measure the impact of their work. If you don’t have an account, go sign up for one today.

After you get credit for your review in Publons take it one step further and connect your Publons account to your Open Researcher and Contributor ID record, or ORCID for short. Or give your publisher permission to do so directly if they offer to do so. ORCID provides a persistent digital identifier for researchers and, similar to Publons it helps researchers to get credit for all their work and professional activities. This is useful to tool to ensure you are recognized for your research, and again if you don’t have one sign up for an ORCID iD.

Many publishers already partner with Publons and ORCID. They understand that peer review activities are often used when assessing a researchers’ performance for promotions, and they want to help ensure their reviewers are receiving proper recognition. Therefore, if you don’t see that Publons or ORCID is offered by a publisher or you can’t add the work to your account on your own, be sure to ask them how to obtain credit for your work. They should be able to provide a record of all your contributions to their journals.

Aside from the content, the peer(s), whether “good” or “bad”, are practically the most important component to the peer review process, so this is a role that should not be undertaken lightly. Do your due diligence to get the review back in a timely manner. Take time to really assess the work and, when you don’t have the time yourself, recommend a colleague. Consider the review process as a way to help advance your field, and provide feedback that is both deliberate and constructive. And don’t forget to make sure you are recognized for all your contributions.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "Revisiting: How to Be A Good Peer Reviewer"

A good reviewer is one who demands her review to be published.

Thanks for sharing!

This is a good article providing a lot of common sense to potential reviewers. While many of the recommendations are generic, there are lots of subject-specific differences in the review process. For a great article on business and economics publishing check out “How to Write an Effective Referee Report and Improve the Scientific Review Process” by Jonathan B. Berk, Campbell R. Harvey and David Hirshleifer in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 31, no. 1, Winter 2017

(https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.31.1.231.}

Thanks for sharing this resource!

As a working scientist who does a lot of peer-reviewing, I feel deeply insulted by this barrage of platitudes. As if we wouldn’t know how to do our job.

One of the issues I sometimes run into in working with academic researchers is an inability to see things from any point of view other than their own. You may indeed be quite skilled at peer review. You may have received superb training in this activity throughout the course of your career. However, others may not be as brilliant and effective as you. Perhaps someone who oversees and manages the peer review process for thousands (tens of thousands?) of manuscripts annually may have insights to offer that are beyond your own limited view of the small number of times you are part of such processes. Perhaps the problematic behaviors described in this blog post actually happen sometimes (never from or to you, of course). Perhaps they see levels of understanding and experience from peer reviewers that may be different from your own superb practices, and may wish to help those individuals live up to the high standards that you present. I apologize if you find this insulting. It must be disappointing to find out that others have not yet reached your level of perfection and perhaps might need guidance to reach that point.

Touche.

Boom! Mic drop.

Well said, David.