Last week, the educational publisher Pearson announced the release of a new app-based service that will allow college students to buy online access to its entire 1,500-title catalog of college textbooks, plus an array of value-added services such as online annotation, flashcards, quizzes, and real-time online support, across multiple devices, for $14.99 per month. (Students can also rent individual e-textbooks for $9.99 each, per month.) Called Pearson+, this product will be a direct competitor to Cengage Unlimited, which was introduced in fall of 2018 and offers students online access to a similar array of textbooks, resources, and support services at similar pricing — with the added option of borrowing a limited number of print copies of textbooks at no additional charge beyond shipping and handling. Now, calling these products “direct competitors” is a bit misleading, as each offers unique educational content and is therefore operating in a market of complements rather than a market of substitutes; in other words, if your professor assigns you a Pearson textbook, you won’t be able to substitute a different textbook on the same topic for that one, and you don’t have the option of buying the Pearson text from any provider other than Pearson, all of which complicates the concept of “competition” considerably. But that’s a topic for a different post.

Anyway. What might be the prospects for this product?

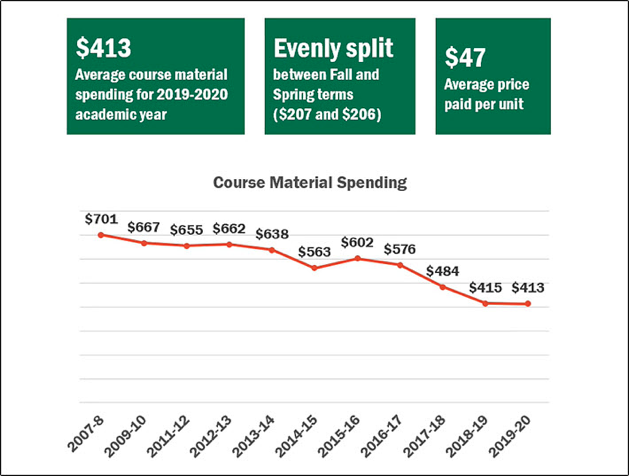

The central question for any new product or service is, “what problem does this offering promise to solve for the consumer?” In the case of Pearson+, one obvious answer to that question is “high textbook costs” — though it is interesting to note that according to data reported by research analyst Brittany Conley (via the Association of American Publishers), the amount of money college students spend on textbooks and other course materials has been falling sharply in recent years, from an average of $691 per year in 2015 to $413 in 2020 (figure 1). Market research group Student Monitor has reported similar findings.

Fig. 1 — Decline in U.S. textbook spending, 2008-2020 (Source: Association of American Publishers)

To the degree that these numbers are accurate, it suggests that the value proposition for products like Cengage Unlimited and Pearson+ may be eroding. After all, if I’m only spending $413 per year on textbooks now, how motivated will I be to get my Cengage and Pearson textbooks online for only a few dollars less — when I’m still going to have to buy my non-Cengage and non-Pearson materials separately at the usual prices? On the other hand, if spending is going down because students are increasingly unable to afford all the textbooks they need, then this would suggest that demand for services like Pearson+ and Cengage Unlimited could be growing.

This brings us to another question one should always ask about a new product: “how much value does it add?” And in response to this question, we can confidently anticipate that Pearson and Cengage will point to the rich array of supporting services and features included in their online products. Pearson+ and Cengage Unlimited are much more than just a bucket of textbooks, they’ll say; the subscription also includes features like online annotation, portability across devices, quizzes and flashcards, real-time online support, etc.

But as with any value proposition, this just begs another question: are you sure the features you’re proposing represent real value to your customers?

If this model does succeed, I suspect it will be specifically because subscribing to the service saves students money on the particular textbooks they need for their classes.

Frankly, I’m not sure that students are going to be attracted in significant numbers by the value-adds of online textbooks — I’m pretty sure the ability to annotate or highlight the books online, or take customized quizzes, or listen to a “non-robotic” voice read the text to them matters much less to them than cost savings. (I could be wrong about that, of course; when I was a college student we were listening to Erasure cassettes on our Walkmans and looking up journal citations in print indexes, and we liked it that way.) Nor, frankly, am I confident that the richness and breadth of the content itself will be as much of a draw as Pearson’s marketing team seems to think it will be. After all, college and university students already have access to far richer and broader collections of online resources than they could ever exhaust, and they’ve already bought access to those with their tuition and fees. Paying a separate fee for access to 1,495 textbooks they don’t need is probably not going to be a huge draw in itself. If this model does succeed, I suspect it will be because subscribing to the service saves students money on the specific textbooks they need for their classes.

But that value proposition alone could be quite compelling in many cases. Here’s a thought experiment: put yourself in the shoes of an incoming college freshman. Imagine that three of your first-semester classes are introductory courses in human anatomy, chemistry, and calculus, and that these Pearson titles are the required texts for those three courses:

- Human Anatomy & Physiology (11th edition) — $160 from Amazon (used)

- Chemistry: The Central Science (14th edition) — $100 from Amazon (used)

- University Calculus: Early Transcendentals (4th edition) — $129 from Amazon (used)

You could buy used physical copies of these three books for $389. Or, for $300, you could buy online access to them from September through May via Pearson+. Or, for $135 — less than half the price of online access to those three titles, and about a third the price of buying used print copies — you could subscribe to Pearson’s complete e-textbook service during that same period.

Now, those numbers may sound high in light of the research I cited above. I’m now putting my third child through college, and I can attest that students buy fewer textbooks — either new or used, in print or digital formats — than they used to. Every semester my son and I sit down and go through the ISBNs of the required texts for his classes, and we investigate the cheapest access option for each one, sometimes renting a printed copy, sometimes buying an e-copy, sometimes renting an e-copy, etc., depending on whether my son expects to want permanent ownership of the content. (He’s a physics major, so we actually end up spending quite a bit more than $413 per year on his course materials.) If only one of his textbooks is from Pearson, then a Pearson+ subscription would not likely be worth it, despite all the additional bells and whistles it offers. If, say, four of his six textbooks are Pearson titles, then a subscription becomes much more appealing. And here it’s worth bearing in mind that I’m a relatively well-off college parent; if our family were less fortunate, the prospect of saving several hundred dollars per school year would be even more of a decision driver.

What this all means is that the market dynamics of the landscape that services like Pearson+ and Cengage Unlimited have to navigate are complicated at best.

In a recent interview with Inside Higher Education, Pearson CEO Andy Bird expresses confidence that “many will buy” Pearson+. After all, he says, “we reach 10 million students a year” with Pearson products already.

But this logic should give pause to anyone with a stake in the success of Pearson+. While I have no reason to doubt that Pearson’s current products “reach 10 million students a year,” it would be unwise to infer from this fact that students feel anything approaching brand loyalty to Pearson, or any other textbook publisher. Students don’t select their own textbooks; they don’t say to themselves, “Let’s see, I’m taking an intermediate biology class — should I buy a McGraw-Hill text or a Pearson one?” Their class texts are assigned to them. I would be shocked to learn that more than a handful of students in the US could even tell you, without looking, who publishes any of the textbooks they are using. In other words, no student is sitting in her room right now asking herself, “How can I get access to more Pearson content?” I also doubt that many, if any, care much about access to online flash cards or the ability to highlight their online textbooks or ask questions of their peers online through a publisher’s platform. (It would be interesting to see some solid research on that question, though.) What I know for certain is that many are wondering how they will pay for college — and some are wondering more specifically how they’ll afford access to the course materials assigned by their professors. Now, the data do suggest that fewer and fewer are wondering that every year. If that’s the case, then the prospects for products like Pearson+ and Cengage Unlimited are likely dimming.

It would be unwise to assume that students feel anything like “brand loyalty” towards Pearson, or any other textbook publisher.

But this suggests another question: Cengage Unlimited rolled out for fall semester 2018, and has been in the marketplace for three academic years now — how is it doing? While Cengage hasn’t publicly provided detailed performance data for this product, it has made public statements at various points. In February 2019 it claimed to have sold one million subscriptions to college students since its rollout in summer 2018. In a conference call with creditors in November 2020, Cengage apparently presented evidence of further strong uptake for Unlimited (though the specific numbers were not made public), and last month it claimed in a press release that “more than 3.3 million college students have subscribed to Cengage Unlimited” — though how many of those have been continuous subscribers since rollout, and what percentage of that 3.3. million represents unique students (as opposed to the same students resubscribing), remains unclear. If we assume that “3.3. million students” represents unique headcount, that tells us that Cengage is adding 850,000 new unique users on average each school year. (For context, there were roughly 20 million students enrolled in US colleges in fall 2020.)

So: students are spending less and less on textbooks and course materials each year, but Cengage Unlimited seems to be achieving reasonably strong growth for its online textbook package each year. This suggests that Pearson (which currently enjoys a roughly 40% share of the textbook market by revenue) has good reason to expect some degree of success with Pearson+. Time will tell, and it will be very interesting to watch. Certainly my son and I will be keeping track of how many Pearson titles he’s assigned during this coming academic year, and who knows — maybe he’ll end up subscribing to Pearson+. It all depends on how the cost/benefit lines up.

Discussion

34 Thoughts on "Pearson Launches a Comprehensive Textbook Solution for Students. What Are Its Prospects?"

I agree that no student cares that much about the add-ons … unless they are quizzes and homework that must be done to pass the course. Which is why I wonder if this as their move into the CMS market vs just a textbook development?

This is why there are people like Ron Vale, who imagined and created XBio (https://explorebiology.org/) as the free learning resource for the students and educators alike!

I’m a bit disappointed that I wasn’t warned this is written solely from the US perspective. I’m actually uncertain if Pearson+ is available outside of the USA, and this is something that I would like to learn from this article. I didn’t learn. In principle, I have nothing against posts for US readers, I think they are the bulk of your readership, but could you warn at the beginning that there is nothing here for me?

Apologies for wasting your time! I guess you can console yourself with the fact that you got your money’s worth. 🙂

I wonder what happens to all the middle dealers in this equation? Where is the bookstore in all this? What kind of institution would be likely to negotiate with either Cengage or Pearson? Or will there even be a second hand market?

As for the middle dealers: cutting them out of the equation is, I’m sure, one of the purposes of offerings like Cengage Unlimited and Pearson+.

As for second-hand markets: it’s hard to imagine what that might look like in an online environment — unless customers are allowed to download digital textbooks and the books aren’t locked into strict DCM regimes.

“Or, for $135 — less than half the price of online access to those three titles, and about a third the price of buying used print copies — you could subscribe to Pearson’s complete e-textbook service during that same period.” Or for free you could probably download them all from an illegal web site. Not something I recommend, but when talking privately to student assistants working in our library, I find that most of them know all about those sites. The publishers must know that they’re competing against “illegal free” and different students (eg rich vs poor ones) are going to have different tolerance levels for costs versus their consciences. And that’s not even taking into account the sharing that happens mostly-legally among students in the same class, and now, we libraries are getting into building print reserve collections of required textbooks in response to overwhelming demand (and willingness to tolerate the inconvenience of it) from our public university students.

Yes, the existence of pirate sites definitely does complicate the marketplace for offerings like Pearson+ and Cengage Unlimited. Library Genesis appears to be down (for the moment, at least) and Pirate Bay no longer seems to offer books at all (let alone textbooks), but I’m sure others like them are popping up all the time.

Many of the pirate sites are in Russia or other countries that don’t enforce US copyrights. They appear and disappear frequently, but Google diligently indexes them all, so that they are easy to find. Google is definitely assisting the pirated-book industry!

I’m interested to know whether US students have access to textbooks through their college libraries? I’m currently a Masters student in the UK and my university provide all necessary books through the library, including physical and e-book editions of compulsory texts and the ability to download the books to read offline. If we require particular books for our assignments we can just make a request to the library and in most cases they will purchase the book if they don’t already have it. It surprises me to think that students would pay to be able to access textbooks online when I would expect that service to be available through their institution.

In the U.S., it is standard practice to leave the purchase of textbooks and course materials up to students. I’ve argued previously in the Kitchen that it’s time for the U.S. to become more like the UK (and, I think, continental Europe?) in this regard, and there has been some movement in that direction in recent years — but the movement has been halting and, frankly, pretty marginal.

As a publisher said years ago: “if you’ve seen one library, you’ve seen one library”…What you wrote as “current standard practice” may apply in many general academic libraries. Special academic libraries (eg. medical) probably not since they’ve acquired reserve copies of textbooks, tried to license online access for required titles, and some (mid-size) medical school libraries now are even reporting that they are managing VitalSource accounts (designed for individual users) and charging back to students’ accounts…All so students have access to the textbooks they need. And OER isn’t common in all health sciences curricula- yet…

There are a growing number of higher ed libraries that are trying to get involved in collecting required texts on behalf of their students, to put on “reserve”. But in most states, this tends to be an ad hoc effort (eg. like my own library, getting what copies we can get for free as donations), as libraries can’t afford to spend their meager book budgets on books that become obsolete every couple of years. In my own case, our entire book budget wouldn’t even cover purchasing one of every required textbook for that year. I know some institutions have prioritized this enough to give the library a separate budget line specifically for this so it doesn’t deplete the regular library book purchasing program. But that’s not common yet in North America.

I am surprised, Rick, that you included no mention of the open educational resources (OER) movement and the pressure it is bringing to bear on textbook publishers in your piece. In particular, the most recent big news out of the OER world is the $115 million investment that California will be making in OER and zero-textbook-cost (ZTC) degree programs at public universities and colleges. California Gov. Newsom signed a budget deal on July 27 that allocates this funding for ZTC programs.

Per Business Wire, “The expansion of ZTC will profoundly impact students across the state and those most in need. Recent surveys have shown that 25% of college students needed to work extra hours to afford course materials. 19% said that they decided what course to take based on the cost of materials. Those costs forced one in nine students surveyed to skip meals. These stresses are only greater since the onset of the pandemic.

“California community college students spend about $700 per year for textbooks. The ZTC program allows students to start and finish their degree programs without paying anything for costly textbooks and other instructional materials.” (https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210728006110/en/Education-Leaders-Students-Praise-Bold-Action-to-Expand-College-Affordability-and-Lower-Textbook-Costs)

The recent surveys this article mentions may refer to the U.S. PIRG report published in 2020 in which ~4,000 students were surveyed regarding their views on textbook costs as well as their buying habits (https://uspirg.org/feature/usp/fixing-broken-textbook-market).

Also not mentioned in this SK post is the fact that commercial textbook publishers’ subscription and digital access platforms used by students come with an unknown amount of data collection, surveillance, analytics, and possible selling of student data that is completely out of the hands of educational institutions because the EULA is between the publisher and the student. In short, some faculty at colleges and universities are requiring students to use publishers’ digital platforms to access their learning materials, and these same platforms are doing who-knows-what with all that data. For more info see this Inside Higher Ed article: https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2019/04/29/report-gauges-potential-risks-scholars-and-universities-if or this post by Billy Meinke: http://billymeinke.com/2018/03/26/signing-students-up-for-surveillance/

It’s great that as “a relatively well-off college parent” you are able to help your son with the cost of his course materials, Rick, but many, many students are not as lucky as your son, and some are even going hungry at times in order to pay for their course materials. With our society’s renewed focus on DEI, I am happy that California’s OER/ZTC initiative along with similar ones in other states will increase equity and inclusion for less well-resourced students by expanding access to and affordability of higher education.

Jody, you’re absolutely right to point out that there are many aspects of the current textbook economy that are not addressed in this piece. My purpose here was to focus specifically on the general model shared by Pearson+ and Cengage Unlimited, and it ended up being a pretty long piece as it is. In case it’s of interest, I’ve written several times about OER, including here, here, and here.

And I hope it was clear that by acknowledging my privilege as a “relatively well-off college parent” in the piece, I was implicitly signaling my awareness that others are much less well off. (Indeed, I pointed to that reality much more explicitly later in the essay.)

I know of at least one community college in Massachusetts, Bristol CC, that has already been offering for years the possibility of completing at least some degree programs with only courses that have no additional materials costs. Students can even, when using the web functionality for searching for courses to register for, filter their searches to courses without such costs (which mostly means courses using OER textbooks). It doesn’t include all of the degree programs, however.

It would be interesting to see the purchase/usage statistics offered in this article compared with usage statistics of open educational resources. I suspect that increased use of open educational resources is part of the reason why students and their parents are spending less on textbooks.

This data would indeed be very, very interesting. Pam, are you aware of anyplace where such data are aggregated?

This is highly doubtful. Piracy and simply going without are probably much bigger reasons. OER is still a niche activity, requiring highly motivated instructors. So many students are taught by adjuncts and graduate assistants.

OER is also generally limited to huge courses that are highly standardized, which means 1st or 2nd year courses. There is little in the way of usable OER for upper-division courses.

This is the free online resource in India..National Digital Library, IIT Kharagpur…will any of you be able to access it and pass it on to those in need?

I haven’t found anything definitive, though haven’t done a thorough search. This article in International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning (https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1163189.pdf) has a section on costs and cites other articles:

International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. November – 2017Volume 18, Number 7. Assessing the Savings from Open Educational Resources on Student Academic Goals.

I Googled “open educational resources impact on textbook purchasing” to find the above article. Most of the results appear to be focussed on positive student learning outcomes and student retention. There are a couple of Inside HigherEd articles that include financial figures (eg, https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/article/2018/07/16/measuring-impact-oer-university-georgia). I’d need to do a more thorough search which would need to be later this week. Perhaps there is a publisher who has done some market research on this.

Good article Rick… like you, I have several college age children and we follow the same process in terms of pricing out textbook costs. I will say with Cengage’s model, the cost for a student per semester is typically $120 or so for unlimited textbooks, and so is probably a bit cheaper than you describe in your example. In a number of cases, particularly in community colleges where there are often more pressing financial needs that students have than paying for textbooks, there is often no cost to the student: https://corporate.cengage.com/news/press-releases/2020/cengage-and-ivy-tech-community-college-partner-to-save-students-money-on-textbooks-and-course-materials/ It would also be interesting to look at the data behind the drop in average textbook cost over the last several years that you mention from AAP and Student Monitor to see if these types of publisher programs have been a factor in contributing to this decline in cost. The $1 million question around textbook affordability is What are you giving up in the way of tools/integration/course alignment/faculty-librarian time in creating more affordable solutions that may affect student success and outcomes?

The $1 million question around textbook affordability is What are you giving up in the way of tools/integration/course alignment/faculty-librarian time in creating more affordable solutions that may affect student success and outcomes?

I agree. In the real world, no economic decision is made with perfect information. And it would be both interesting and important to know what percentage of the foregone textbook purchases arise from indifference (“Eh, I don’t think I need this textbook really”) versus economic forcing (“I wish I could buy this textbook, but if I do I won’t be able to buy groceries for three weeks.”).

This is not a $1 million question. It is a $10 billion question.

The launch of Pearson+ and Cengage Unlimited should be understood in the context of the industry’s “end game,” which is courseware, not ISBNs, and disintermediating all middle vendors and aggregators. There is as much marketing of these “all you can eat” solutions to the universirt adminsitration as therre is to students. Pearson, Cengage, McGraw Hill, etc. envision a world where students purchase access to courseware (with text integrated tighgtly with other media and adaptive technology) either directky from the producer or access via an LMS embed with the fee embedded in tuition and fees.

Like David Parker above, I wonder how much of this is a play for faculty and/or administration, but from a different angle. I know that many faculty members consider the cost of the textbook they are looking at assigning to students as a factor in textbook adoption. Might these kinds of offering push more faculty to select the same publisher as their colleagues? Are Pearson and Cengage marketing these offerings at the professional meetings as a selling point?

Marketing seems to be entirely to administrators—faculty either select books on fit to their course or on price. Administrators are much more attracted to all-you-can-read buffets.

It seems like getting students to obtain accounts and apps from a vendor that in turn collect huge swaths of data from student devices — none of which is controlled, managed, or particularly well understood is a big business opportunity. The students are the product and the market. It sounds like a path to cutting out a lot more than the “middle vendors.”

don’t know if this has been referred to before but a couple of faculty from San Jose State have done a fair job of piecing this all together.

see: The case of Canvas: Longitudinal datafication through learning management systems Roxana Marachi & Lawrence Quill To cite this article: Roxana Marachi & Lawrence Quill (2020) Teaching in Higher Education, 25:4, 418-434, DOI: 10.1080/13562517.2020.1739641 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1739641 Published online: 29 Apr 2020.

ABSTRACT The Canvas Learning Management System (LMS) is used in thousands of universities across the United States and internationally, with a strong and growing presence in K-12 and higher education markets. Analyzing the development of the Canvas LMS, we examine 1) ‘frictionless’ data transitions that bridge K12, higher education, and workforce data 2) integration of third party applications and interoperability or data-sharing across platforms 3) privacy and security vulnerabilities, and 4) predictive analytics and dataveillance. We conclude that institutions of higher education are currently illequipped to protect students and faculty required to use the Canvas Instructure LMS from data harvesting or exploitation.

Thank you for the article — it is very concerning.