Last week, David Crotty wrote about “Market Consolidation and the Demise of the Independently Publishing Research Society” in which he described the quickly converging landscape of society publishers. These societies are not merging together, per se, but rather merging with a very small group of commercial publishers.

David argues that these partnerships have accelerated in the last few years over pressures felt by society publishers to comply with complicated requirements of Plan S and other funder policies. This was well predicted and really astounding given the underwhelming number of signatories to Plan S.

Since Plan S was announced, there were predictions that it would embolden and make larger the biggest of commercial publishers. Whether this was a feature or a bug is still being debated.

As David pointed out in his post, smaller publishers and society publishers worry about complying, but also the move, particularly in Europe, toward so-called transformative agreements (TAs). Much like when “The Big Deals” started rolling out to market, independently published societies are afraid of being locked out. How do they get a seat at the table? What happens if a society with similar content is included in a TA and you can’t even get in the door?

These concerns, coupled with issues around society finances, uncertainty around open access, and general market volatility work in concert to push self-published societies into the arms of a commercial partner.

One of the benefits of moving to a commercial publisher is that you no longer have to manage (or directly pay for) vendor services — typesetting, copyediting, online hosting, enhancement features, metadata maintenance, printing, distribution, manuscript submission and review systems, sales support, etc. Further, due to the efficiencies of scale, the commercial publishers are paying less for these services than independent societies. Having recently transitioned a program from self-published to commercially published, I can tell you that this is 100% the case.

What does all of this mean for the vendor landscape? We have seen several examples of consolidation or the outright purchase of vendors and services by commercial publishers:

- Atypon to Wiley

- Aries to Elsevier

- eJournalPress to Wiley

- J&J Editorial to Wiley

I am sure there are others that I am forgetting about. I have written before about the implications to a society publisher when your vendors are all owned by commercial publishers. But what happens to the industry in general when choices are slim and getting slimmer, particularly when this comes to platforms and peer review systems — all huge expenses for society and small publishers.

One likely response is that innovation will suffer. In today’s landscape, would HighWire ever have been born? HighWire (now owned by MPS) was built in response to society publishers needing an online home for their journals. Unencumbered by the needs of a Wiley or an Elsevier, HighWire was an early partner with Google and had tight relationships with the library community. HighWire was exactly why many society publishers could stay independent during the tumultuous move to online journals.

But again, is there space for a new “HighWire”? What are the incentives of innovation when more and more journals are consolidated under very few publishing houses? Without a customer base, there is no investment. A new entrant will find it very difficult to build enough support to justify financial investors. And without that growth, likelihood of being acquired is low.

Even if you build a better mousetrap, if there are no customers, you won’t get very far. The barrier to entry for any new player seems nearly impossible. This is not good for any industry and makes us particularly vulnerable to disruptors outside our space.

Speaking of vulnerable, there are still a handful of companies that cater specifically to small publishers and independent society publishers. When a society’s journals move to a commercial publisher, it’s not likely that the commercial publisher will need to add sales staff. And their use of vendors for sales support shrinks as they get bigger.

Likewise, the many consulting services that cater to our industry will facilitate fewer and fewer RFPs and find fewer societies that want help to stay out of the hands of commercial publishers.

Typesetters that cater to smaller publishers are likewise vulnerable as the large publishers use the largest of vendors almost exclusively. If you are having trouble following the name game these past few years, you are not alone.

- Sheridan and related companies announced they would be under the parent company CJK. Then they bought Cenveo (also a mashup of publishing companies of the past, namely Cadmus and Mack), all under the name of KGL. Recently they acquired Kaufman Wills Fusting (KWF), provider of consulting and editorial services.

- The company formerly known as SPi Global is now called Straive, which acquired Scope e-Knowledge and Scientific Publication Services (from Springer Nature Group).

Clearly the name of the game is survival of the fittest. Many of these companies are also serving industries outside of scholarly publishing, which helps in diversifying their revenue streams.

It has become less and less certain that medium and small societies will continue to benefit from being self-published in the medium-to-short term. Their options for vendor services are shrinking and becoming even more dependent on commercial publishers — as a partner or a vendor.

As more independent societies make the move to commercial partnership, the smaller our industry will get, which is ironic given the massive increase in scholarly content being produced.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "The Future State of Our Scholarly Publishing Vendors"

Without disagreeing with any of the above points, I would also point out how much easier it will be to build publishing technology. XML Generation, for example, is going to become less important in the age of Inera. Just like there was originally just Highwire and now there are countless vendors, new technologies like Inera (Automatic generation of XML from a Word document) will draw out new individuals who see a gap in the market.

Some other benefits of a growing technology sector:

⁃ A strong relationship with Google may no longer be as necessary, as more and more people in the market have accurate SEO knowledge.

⁃ The low cost of cloud computing platforms may mean that custom XML processing software may become obsolete.

⁃ As existing vendors move to outsource more and more of their own services, they will become themselves an amalgamation of vendors, meaning their core code base will become easier and easier to replicate.

And lastly, neglect. As larger companies get comfortable with their big customer bases, they will stop investing in their platforms (as they don’t see new revenue opportunities) and create market gaps of their own. I’d argue that we’re seeing this already.

It’s my hope that the market forces I’m describing can overcome the market forces you have described, and the lower cost of technology means less customers will be needed to start new vendors.

Thank you for the counter points, Andrew. I don’t doubt that what you say above could happen. I don’t think it will benefit self-published societies. Here is why: reduction in costs to the output of digital content will require an expertise on staff that may not currently exist. The conversion of word to properly parsed XML has been a dream, but has not worked yet. We should note that Inera is now an Atypon company, which is a Wiley company (I know you know this as you work there:). So amazing advances that could be made by Inera to streamline the workflows will allow Wiley a better end-to-end solution. Now before I get too far, the conversion part is but one piece– there is QA, custom tagging, proofreading, print layouts (yes, still), author corrections, etc., that require people. This does not currently exist within Atypon. So the solution may be elegant, but will require the journal to have expertise on hand to do all the things that a typesetting vendor might do today. That would be a hard sell for all but the biggest self-published societies.

I will keep an eye out for the up and coming vendor that might show up and sweep us all off our feet!

Angela I am not sure even the large society publishers will remain independent. Cost analysis will move them to signing with the large commercial publishers. Their costs will drop dramatically and make up for dwindling membership and meetings. After all, not for profit does not mean profitless!

I think I agree with you. The librarians who are basically the society’s customers are not concerned about this. The only group who may have reservations could be the EU or the Justice Department if too much of the market is dominated by too few vendors, but I can see the argument made that if the academics don’t complain and it’s saving money, it’s fine to allow (see book publishing).

Perhaps we shouldn’t wait on new vendors, but instead accelerate collaboration and partnerships between society publishers. Both your piece and David Crotty’s post a couple of week’s ago (see Market Consolidation and the Demise of the Independently Publishing Research) present only two options for independent society publishers’ survival – either merge or move to a commercial publisher. However, there are viable alternatives such as nonprofit cooperative enterprises such as GeoScienceWorld (GSW) and BioOne.

Following the model of BioOne, GSW was founded in 2004 with a mission to enable geoscience society publishers to better serve their discipline, their members, and the larger geoscience community through collective action. The GSW collaboration has been successful in part because of these key factors:

1) A founding vision of a nonprofit aggregate that benefits both small and large geoscience societies,

2) A business model that distributes more than 90% of earnings back to our partners, which get reinvested back into the discipline and the community,

3) A deep understanding of the geoscience research communities in which we serve,

4) An unbiased, independent staff with a mission to sustain all partners, and

5) Board representation from libraries, the research community, industry, and small and large societies, all of whom support the founding mission.

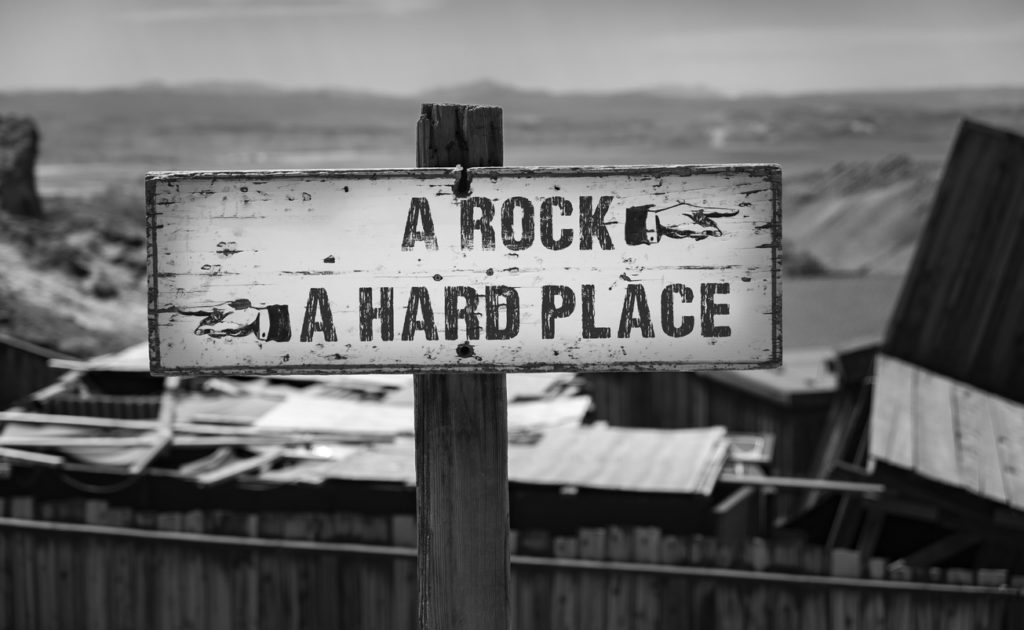

The acquisition of vendors by commercial publishers has accelerated and the consolidation certainly provides an opportunity for new vendors to emerge. However, I can’t help but think of the opportunity that is emerging for society publishers that share similar missions and goals – is it possible that the cooperative model like that of GSW and BioOne may offer an alternative to the rock and the hard place?

Hi everyone –

cOAlition S and ALPSP are jointly sponsoring a third phase of the SPA OPS project, to support scholarly society publishers to accelerate their transitions to open access. The focus of phase 3 is to facilitate OA agreements (e.g. Read & Publish, Subscribe to Open). Working groups of library/consortia representatives and independent society publishers have worked closely to develop shared principles, model licenses, data templates and workflows.

Automation will enable more society publishers to embrace these opportunities. Platform and system providers are invited to a free webinar to find out more. If you would like to attend, please register here: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/towards-greater-automation-of-open-acess-agreements-tickets-239920668177.

Automation will be