Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Mark Huskisson. Mark is the Publishing Development Specialist at the Public Knowledge Project and the co-chair of the Assembly of the Commons for the European Research Infrastructure, OPERAS.

A Spanish language version of this article is also available.

Each year, the Public Knowledge Project* (PKP) posts a very large, and rather dry, dataset at the Harvard Dataverse Project. This open data provides a summary of the known installations of PKP’s open source publishing software around the world (OJS for journals, OMP for monographs, and OPS for preprints). When we released the data this year, a number of challenging questions were raised about the rapid growth of OJS in particular – quite rightly, as “open means open” and that includes being open to interrogation and challenge. But it also means, for many of us, a need for openness as we recalibrate and broaden our understanding of the current scholarly publishing landscape.

The scale of the adoption of PKP’s open source publishing software around the world may be surprising, but the numbers should be a cause of celebration, for they are a demonstrable improvement in global knowledge exchange. They reflect an increase in engagement, participation, and diversity of contribution to the global scholarly knowledgebase, in origin, language, purpose, and the generation of research and data to find solutions to local and global issues from a new perspective and through a different lens.

Ginny Hendricks (Community Director at Crossref), was quoted in Nature, “People may be so obsessed with Plan S and Europe that they’ve taken their eye off the ball on progress in other countries.” And when analyzing last year’s dataset in Recalibrating the Scope of Scholarly Publishing, PKP’s Research Team conclude that scholarly communication is more of a global endeavor than is commonly credited.

So, pull up a chair in the Kitchen and we’ll take a look at some of the numbers and try to throw some light on the shade that is cast by some of the assumptions and claims about OJS and publishing in the Global South. But of course, as this is open data, you can always interrogate the data yourself without my commentary.

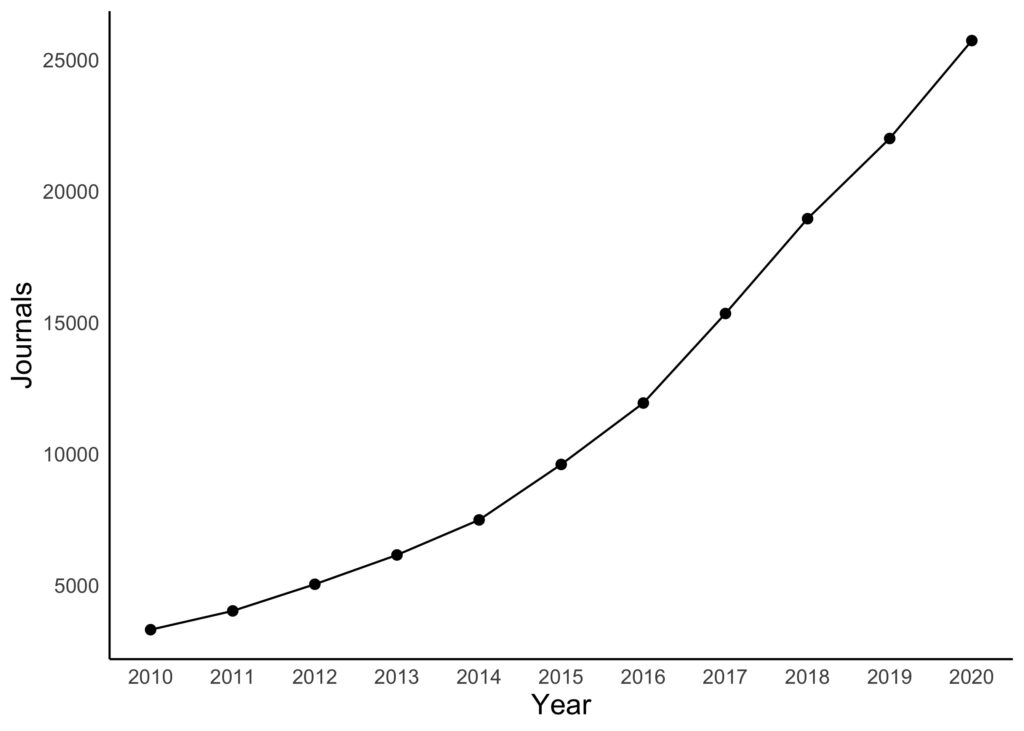

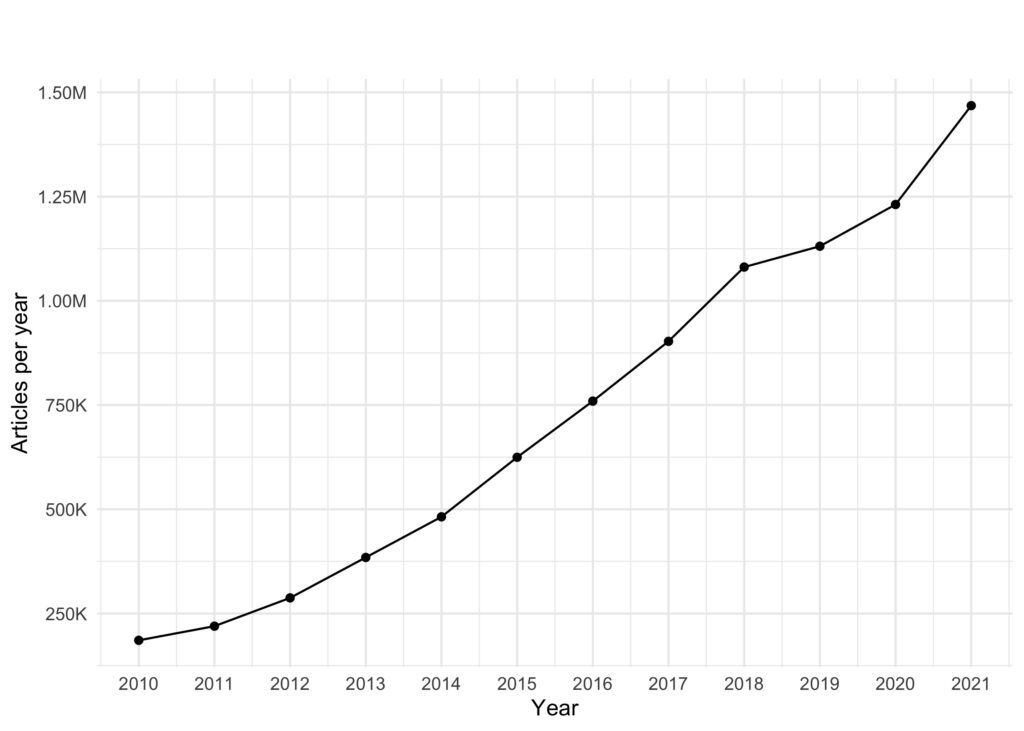

The headline numbers for OJS in 2021 indicate that 1.46m articles were published by 34,071 active journals on approximately 12,000 publisher and institutional installations. To give context to these numbers, Elsevier’s portfolio published ~600,000 articles in ~2,700 journals in the same year. These past few years have seen a significant acceleration in the proliferation of the number of journals and the number of articles published on open source software.

The growth in journal and article output, in itself, is not indicative of anything other than an increasing quantity of output, so a better understanding of what underpins these numbers is essential. What becomes increasingly clear and apparent as one interrogates the data is the development, fostering, and nurturing of bibliodiversity through this rapidly growing global ecosystem of open source tools developed and used by locally published journals.

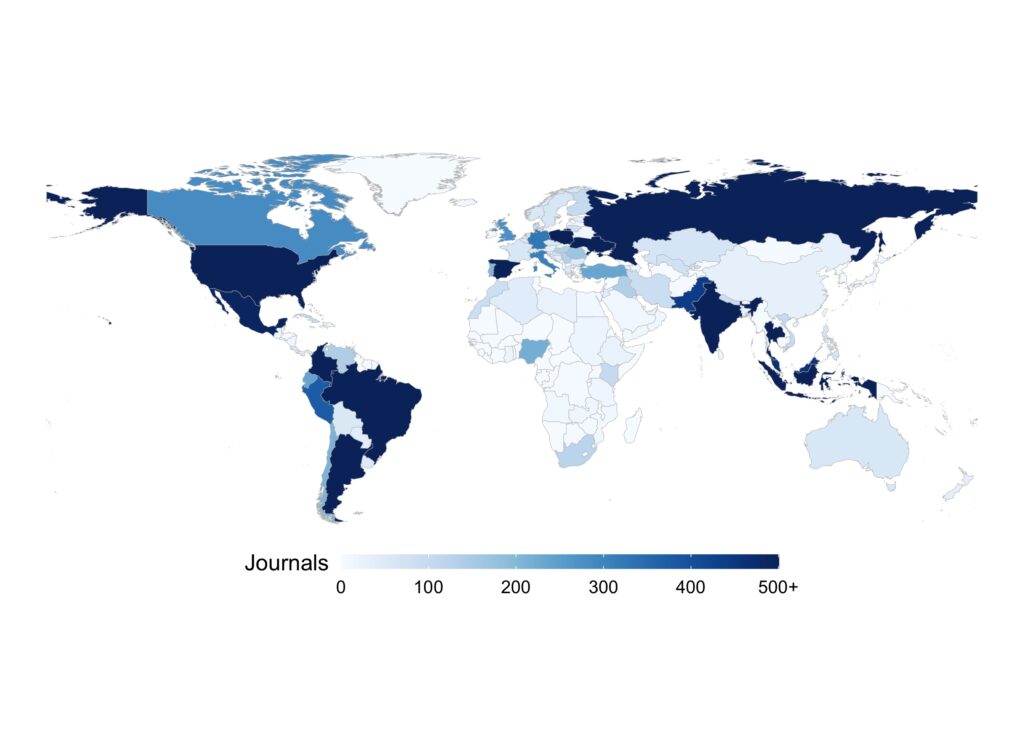

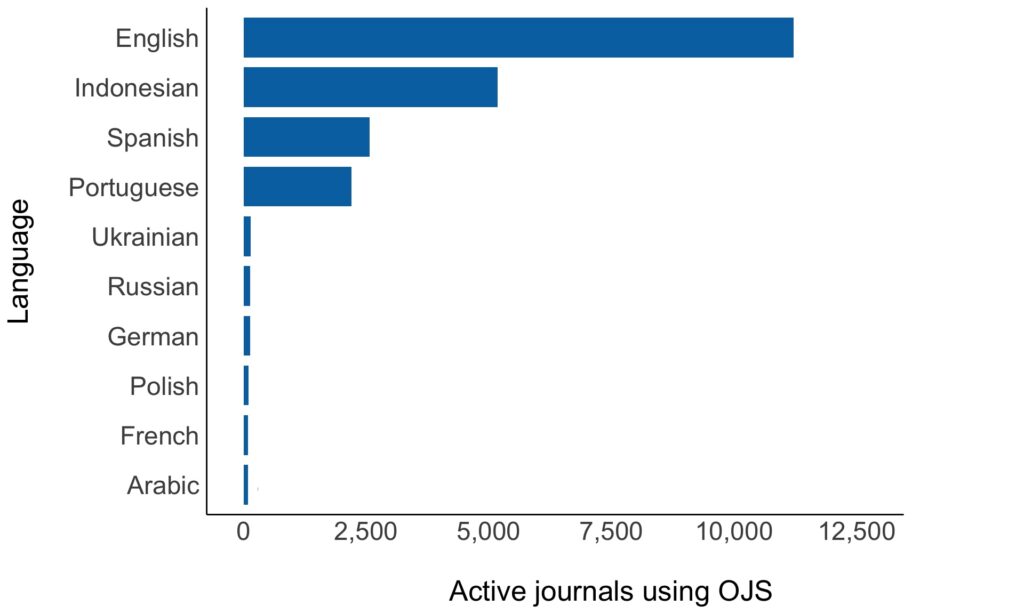

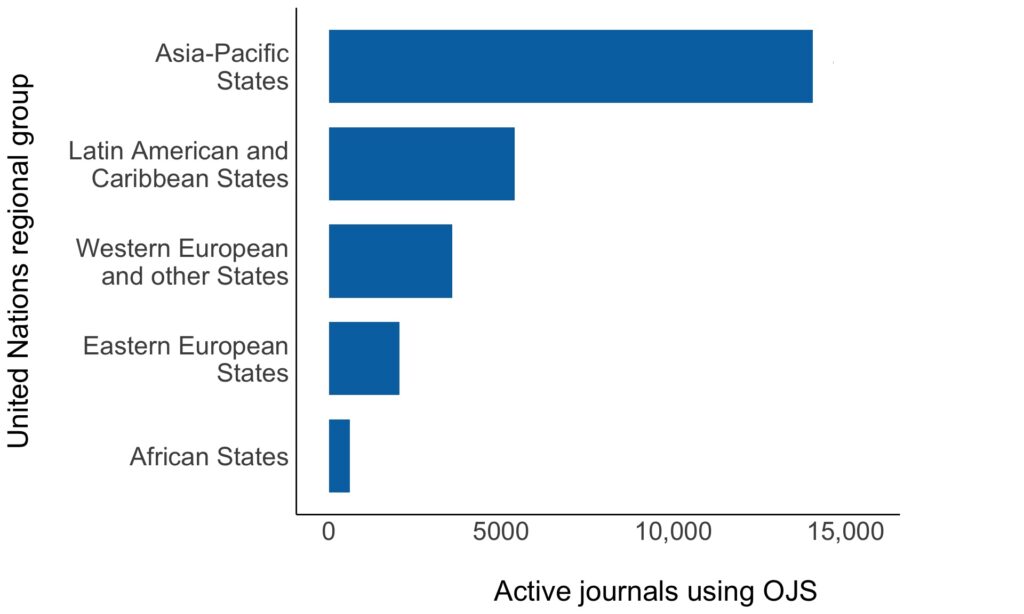

For the users of OJS, this is research published in 60 languages from more than 146 countries (~80% are from the Global South). Aligning with the international array of signatories to the 2019 Helsinki Initiative on Multilingualism to create diverse communicative spaces, a substantial proportion of these journals operate in more than one language.

This dataset begins to cast light upon another world of scholarly communication that is more broadly global, diverse, and inclusive. This world is evolving concurrently to the commercial publishing context that is normally discussed and assumed as our institutional norm at our conferences in the Global North or over our coffee in the Kitchen.

In the twenty years since the Public Knowledge Project (PKP) first released OJS, it has grown to become, by some measures, the most widely used journal management and publishing software in the world, enabling hundreds of thousands of researchers to publish their research, in their own language, and made fully discoverable by global indexes. But this rapidly developing world remains largely invisible to the majority of us who work in scholarly communications in the Global North. The data would seem to indicate that this vast and growing ecosystem has flourished beyond and outside the hegemony of commercial publishing and, as such, challenges many of our basic understandings of the scale and activity of academic publishing as a scholarly endeavor.

I suspect that the significance of output outside of the publishing centers of Europe and North America goes largely unheeded due to a shared reliance upon commercial indexing services that only harvest and report upon a fraction of the output from the Global South. For example, the Web of Science indexes and reports on only 1.2% of journals that use OJS, Scopus 7.2%, and EBSCOHost 3.4% of journals on PKP’s software (by contrast, Google Scholar indexes around 90% of journals using OJS).

This lack of indexing translates into a severe lack of visibility in the commercial mainstream and allows doubt and shade to be cast upon the value of publishing in the Global South. Some commentators extrapolate this absence of indexing, and the subsequent lack of inclusion in our conversations, as a reason to question the credibility and validity of research outputs.

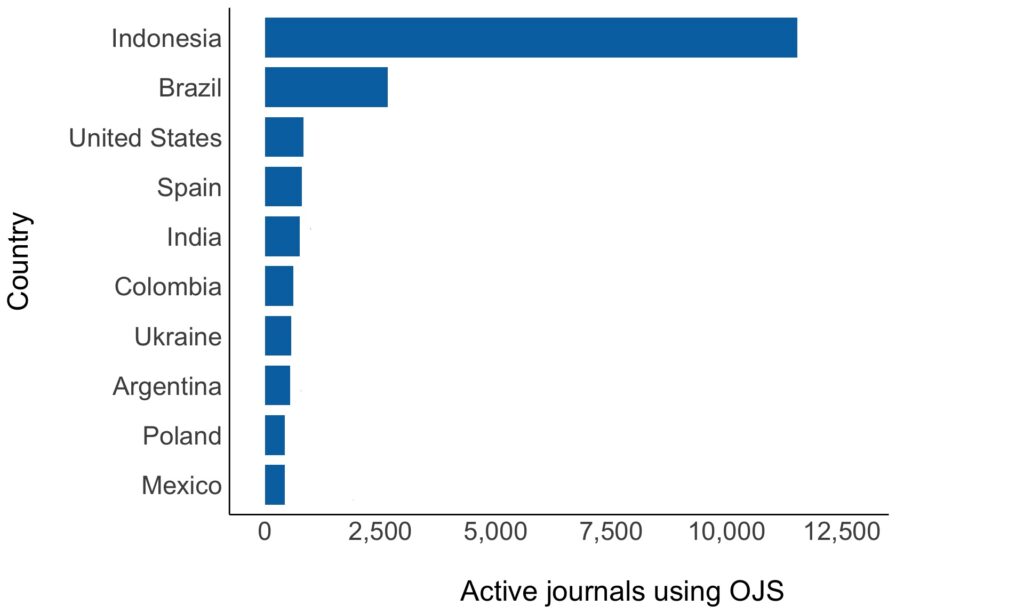

When looking at the above chart you can’t help but be drawn to Indonesia with 11,536 active journals on OJS. We should not be surprised – not only is Indonesia the fourth largest nation in the world, but it is also the world leader in the number of open access (OA) research journals. This rapid growth is a consequence of Indonesia’s 2019 Law on National Knowledge System and Technology which requires the implementation of (OA) licenses to ensure the public can access and use research results, hoping to not only encourage transparency on research processes but also to disseminate innovations and findings that benefit the public.

Elsewhere, the success of SciELO, Redalyc, and other Latin American initiatives have championed a huge growth in publishing from within Latin America since their inception more than twenty years ago, improving the overall quality of science in Latin America and solving problems relevant to the region – much in Spanish and Portuguese. Hebe Vessuri [CIGA-UNAM] states that “Latin America is using the OA publishing model to a far greater extent than any other region in the world … because the sense of public mission remains strong among Latin American universities … these initiatives demonstrate that the region contributes more and more to the global knowledge exchange while positioning research literature as a public good.”

As with SciELO, commercial partners that turn to open infrastructure projects such as PKP can serve the long-term sustainability of software in open infrastructure. The recently acquired Ubiquity Press is a case in point. Hosting over 700 journals on OJS, Ubiquity is one of a growing number of for-profit commercial publishers and content platforms that are increasingly aware of open source publishing solutions, benefiting from developing shared code that is outside the control of a commercial competitor.

Open source platforms are used extensively in industry sectors that rely upon technology, so it is somewhat unusual that academic publishing has largely bucked this trend to date. It is common to see competing enterprises contribute toward developing open source infrastructure to their common benefit, from which they develop solutions on top of this infrastructure – quite often for profit. It is something people such as Katherine Skinner, formerly of Educopia and Next Generation Library Publishing (NGLP), has long championed, the adoption of open source tools that align publishers and libraries with the larger scholarly mission – but not to the mutual exclusion of commercial resilience.

So it isn’t unusual that OJS, as with many other open source tools in scholarly communications, has begun to attract a growing number of commercial partners. PKP has established a role of community development for the shared common benefit for its users, who contribute development, resources, and support for the open source software upon which they themselves then build services and solutions. Outside of commercial solutions are a growing number of initiatives such as Scottish Universities Press based upon PKP’s OMP, which share an “appetite to explore alternative approaches to academic publishing, that are of the academy and have the needs of the academy at the core.”

The surprise is that there is so much surprise at all. The rapid growth of OJS as an open source solution in publishing is attractive to thousands of researchers and journals who require a low-cost, high-quality solution. For commercial publishers and platforms, it is a solution that will remain outside of the control of competing commercial publishers and benefits from shared and unified resource development at scale. These same solutions work well in parallel industry sectors where open software platforms have been built in common and from which commercial solutions are built, whether for profit or for the public commons.

The growth we see in this year’s numbers is not exclusive to the software from PKP. We see similar percentage growth for multiple open source solutions. And growth is expected to continue as open infrastructure is invested in heavily by both commercial and national funders, such as new funding for Redalyc at the Autonomous University of Mexico State in Toluca, for Érudit to build open, non-commercial infrastructure for sharing research at institutions across the world, for initiatives to support institutional OA publishing such as DIAMAS, CRAFT-OA, and future collective publishing enterprises by the European Commission, as well as initiatives like CRKN’s structural support for Coalition Publica to support to Canadian journals in the transition to a fully open access model.

For those who support and contribute to PKP’s global work, the scale and the achievements of the project over the past two decades are quite humbling. Since OJS was first released in 2002, it has become the most widely used scholarly publishing platform in existence. It has enabled researchers around the world to participate, engage, and enrich the bibliodiversity of a publishing system that was – to the global detriment – framed by and largely focused upon research and institutions of the Global North, where English became the lingua franca of research and heightened the barriers to participation and access to knowledge for the vast majority of the world’s population. That has begun to shift, and rapidly, beneath our feet.

[*Note: Founded in 1998, PKP (https://pkp.sfu.ca/) is a research and development initiative at Simon Fraser University and Stanford University]