Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Jess Ludwig. Jess is Director of Product Management-Digital Humanities at Gale.

In Jorie Graham’s poem “The Way Things Work,” she uses the language of engineering (“Wheel, kinetic flow, rising and falling water”) and faith (“I believe in you”) in her exposition of the world. She invokes numerous tools including keys, ingots, levers, and in Graham’s anthropomorphic crane (“your head is the horizon to my hand”), the machine becomes an exalted extension of the human body.

I have led product management teams that create educational research and instruction products in close readings of Graham’s poem. Our conversations cover diction and form (many of us are humanities students, after all!), but we primarily talk about the poem as it relates to digital product management best practices — transparency, awareness of and advocacy for user needs, data-informed decision-making.

Artificial intelligence, or machine learning, systems that are trained on data to describe, predict, prescribe, or create have arguably made an awareness of how digital tools, platforms, and services actually work even more essential. We must consider how these models and tools are built, including the data and data sources on which they’re trained, the limitations of those sources and data, the ethics involved in training models, and many more questions. Within this context, the data literacy skills to interrogate all of those areas and navigate both academic and professional careers that are increasingly data-focused become even more important.

Data literacy emphasizes how to access, evaluate, manage, analyze, and ethically use data, and scholars and librarians often fold data literacy within ACRL’s Framework for Information Literacy. Given the prevalence of data in our daily lives and the likelihood that both the volume of data and the use of artificial intelligence will only increase, new data literacy and artificial literacy standards are necessary and emerging.

The digital humanities, with its focus on digital tools, texts, and computational methods, requires students to work with data in a variety of ways, largely through the artificial intelligence subfield of natural language processing. Undergraduate and graduate courses typically have assessments and capstone projects that invite students to sharpen their data literacy skills by performing both qualitative and quantitative research. The workflows and iterative mindsets these digital humanities projects involve must inform future data and artificial intelligence standards and competencies. Here are just a few areas that deserve attention and emphasis:

Access, Evaluate, Use Data

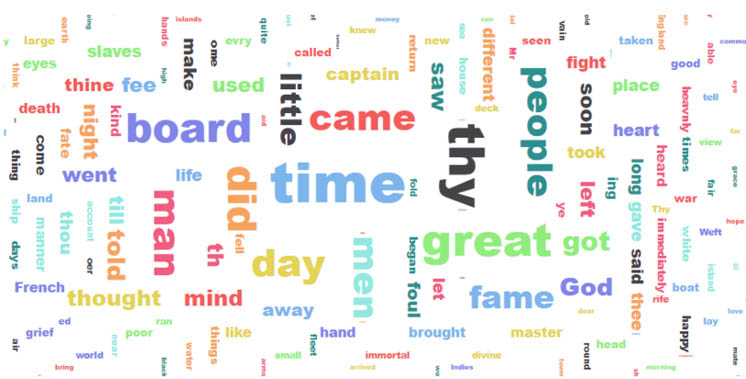

- When students consider text computationally, they need greater awareness around data’s possibilities and limitations. For example, how different editions of texts, newspapers, and poems can vary not only based on edition, publication year etc., but also based on the digital technology used to scan collections. As optical character recognition technologies have changed, so have document transcriptions and potentially the resulting research conclusions from this data.

- Students need to understand different file formats and why and when they should use them based on their research needs.

- Students also need to know the questions to ask around copyright and fair use, ethics, and privacy. Are additional permissions needed to perform text and data mining and create visualizations of collections? Once data is uploaded into a platform or repository, what happens to that data?

Manage Data

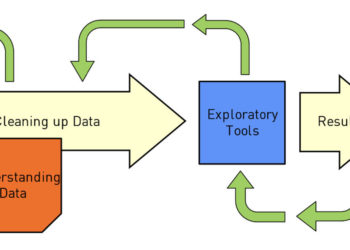

- Preparing data for analysis is often an inscrutable process for people new to text and data mining and visualization. It involves understanding the structure and information contained in the data and usually requires iteration and problem-solving skills. What happens when you remove certain terms from a text analysis? Whole sections of text?

- How much information should you provide your audience about the choices you’ve made about your data? The tools you’ve used to process data?

Analyze Data

- The stories that can be told with data and the claims that researchers can make are often in dialogue with the decisions that tools developers have made about a program or platform. How are the tools you’re using to analyze data built and by whom? What are the benefits and limitations of these tools from user experience, data processing, data replicability standpoints?

- A digital humanities capstone project may require students to create highly interactive digital exhibits that explore a research question. These project-based exhibits often involve managing data across multiple digital tools and platforms, which develops technical competencies and an awareness of the strengths and limitations of a platform’s user interface, metadata descriptions, and data representations, among other elements. Or more advanced students may write new or use pre-existing Python programs to parse data, which also raises evaluative and creative questions.

Working with data in these ways develops analytical thinking skills that encourage students to question how digital tools interact with data and how their decisions — as well as the decisions made by data curators and digital product developers — influence research results. A digital humanities critical mindset that includes understanding how digital tools, products, and services work is important to understanding artificial intelligence and is useful for practically all professions that students enter after they graduate including teaching, marketing, communications — and digital product development.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Digital Humanities, Data Literacy Skills and AI: Understanding the Way Things Work"

Great reasons why we need to demand transparency from AI makers. Right now most of them don’t allow us to scrutinise their solutions and they even’t won’t allow AI chatbots to ‘know themselves’ or report any issues back to their makers. Meta seems to be walking a different path, which looks promising: “The public experimentation aspect of open source technology allows for greater scrutiny, providing an opportunity for a community of users to assess Llama 2’s strengths and weaknesses, including its vulnerability to attacks. The public’s watchful eye may reveal flaws in LLMs, prompting the development of defences against them.” https://theconversation.com/why-meta-is-allowing-users-to-see-the-inner-workings-of-its-new-ai-chatbot-210079

Excellent questions posed throughout this article that should be considered when selecting, sorting, creating, storing and especially when sharing data. Transparency and source citing are key – and the source investigated for authenticity.

Important point you are making here: “… awareness around data’s possibilities and limitations.”

Data can lead you to text. But once you are there, you have various options for its reception. You may call it “reading” on the surface, but it can differ in many ways: Scanning for keywords, scrolling through long lists or text, browsing through an article, reciting loudly with a focus on language patterns or sheer beauty, proof-reading etc.

“Text” still covers many different levels of information beyond mere semantics.

• visual appearance: fonts, alignment, material used to print/write on etc. (compare e.g. the html-version of the poem you referred to with printed or PDF versions. And of course, the etymology of “text” – derived from Latin “to weave”.)

• non-linear information: footnotes, images presented in context, comments on the side (think of Talmudic literature, or also some of Max Weber’s works, or of Friedrich Nietzsches’s autographs.)

• quotation and insinuation, irony, ambiguity…

And that leads to the notion that besides the importance of digital data and text – print is far from being “dead”.

• Especially in the Humanities of course – it is more than just an archival copy.

• And in today’s language the old usage patterns of “print” stay alive – both literally and figuratively. “Scrolling” through a long text on screen today can be equally annoying as it probably was 2000 years ago, when you wanted to read again that first paragraph after having rolled up a meter of your “scroll” …

• … which lead to the invention of the codex, where you could finally “browse” through pages and get to that first paragraph quicker… (And as PDF downloads still have a big share in COUNTER reports, people still seem to be producing their personal “codices”)