Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Karin Wulf and Amanda Strauss. Amanda is Associate University Librarian for Special Collections and Director of the John Hay Library at Brown University.

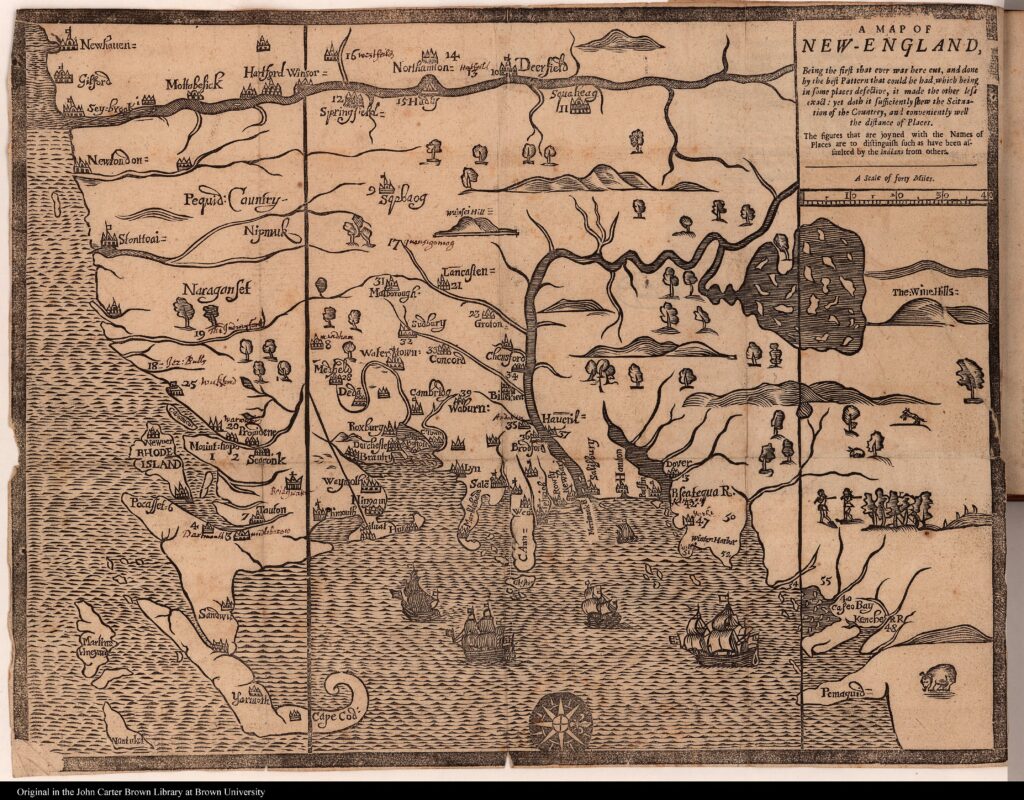

The first map of New England attributed to settlers was printed by John Foster in William Hubbard’s Present State of New England: A Narrative of the Troubles with the Indians in 1677. Both of our special collections libraries – the John Carter Brown Library, an independent library at Brown University, and the John Hay Library, part of Brown University Library – hold copies of this rare and important representation of settler ambitions and colonial imagination. This map can be analyzed and described in any number of ways that are attentive to the contexts of colonialism that produced it and equipped institutions such as ours to collect, preserve, and make it accessible. From an institutional perspective, we can consider how colonialism gave it such value, how it came to be in, and is now situated within our collections. Equally, we can consider how the perspective of the mapmaker and its intended contemporary audiences continues to influence that value and situation. As the jointly appointed curator for Native American and Indigenous Materials Kimberly Toney describes it,

“The map served as a visual guide to the book’s recounting of the events of King Phillip’s war, and is intentionally disproportionate, highlighting sites of conflict during the war between colonizers and several northeastern woodland tribal nations….The startling orientation of the map, with West at top, invites us to reflect on the place and time represented by the data points on the map, and the histories of dispossession and disorientation experienced across the Native homelands foregrounded here.”

The critical tools for this kind of analysis have emerged in the last decades from two separate and often siloed fields with distinct methods, practices, and scholarship for studying the historical materials that reside in archives and libraries. We have been surprised to find that too often the urgent work of considering archival and library materials remains likewise siloed. While some do, too often archivists and librarians on the one side and scholars on the other are not engaging one another’s work or are even aware that each has long been engaging with important issues in critical archive studies. We should more regularly join the scholarship from each of these perspectives and collaborate across professional and disciplinary positions.

To be sure, though it looms large in both of our professional lives and is reflected in our own backgrounds, we still struggle for the appropriate phrasing to describe the bifurcation between those whose professional appointments are within libraries and archives acquiring, describing, and processing the materials, and those whose professional work most often places them in the role of reading room researchers using these same materials. Surely bifurcation and siloes emerge somewhat naturally through different paths of professional training and experience, which create distinct knowledge bases and professional networks. But we acknowledge that even describing this gap has often implied that librarians and archivists are not scholars. We could purely describe training, (MLS or PhD), but that distinction too is incomplete. The preceding formulations also exclude those who work on cultural heritage outside of the academy. For the purposes of this post, we shorthand this complicated landscape as “archivists and librarians” and “scholars” even though we realize it replicates the problem we are highlighting.

A profusion of scholarship has emerged from scholars in history, literature, and other humanities disciplines taking libraries and archives themselves as their subject of study. The institutional histories of private familial, corporate, and government archives, as well as the nature of private and public libraries, show us a remarkable story of how information ecologies and priorities emerged out of specific contexts. One of those contexts is colonialism, both the institutions that emerged to serve colonial interests (government and company entities in the early modern west, for example) and to serve colonial presumptions and values (about collecting, for example). Other scholars have examined how specific types of archival or library materials reflect historical contexts and the presumptions and values of their creators, and have offered methods for how they should be analyzed as such. From Marisa Fuentes and Ann Laura Stoler to Ann Blair and Jennifer Morgan, scholars of the early modern world and specifically of empire and colonialism have pushed to the fore questions of how we understand these periods and subjects as inextricable from an accounting of the historical materials they produced and the repositories that hold them.

For archivists and librarians, the turn to critical archives accelerated twenty years ago when Dr. Terry Cook published in close succession two articles that would permanently reshape the field: — “Archival Science and Postmodernism: New Formulations for Old Concepts” and “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory.” Cook was one of the first to offer an alternative to the waning but still tenacious notion of archival neutrality. By the early 2010s, another formative wave of archival scholarship emerged — the social justice turn. The long list of influential work that urged the field to embrace its influence with a purposeful, justice-driven agenda and firmly placed archivists in the U.S. in a global conversation includes scholarship by David Wallace, Michelle Caswell, and Joel Blanco-Rivera. Contemporary critical archival theory intersects with the ethics of care, memory studies, Indigeneity, Blackness, liberation, and a reckoning with racism and colonialism. This theoretical work deeply influences archival practice. In meetings within our own libraries as well as at local, regional, and national gatherings, descriptive work, processing and cataloging, reference services, and more are evolving as archivists and librarians grapple with the history of our profession and the imperatives of the present moment.

These two approaches to essentially the same sets of questions – how do we study not only the artifacts within a repository, but the nature of its production and appearance in our institutions – can obviously benefit from the scholarship of both fields. To return to Foster’s map in Hubbard’s Present State of New England, a traditional source about a place with a long tradition in libraries and scholarship, we might bring these two perspectives to bear. In our libraries, the book is cataloged in a particular way, reflecting classifications developed in the early twentieth century that privilege, for example, the author and title. It is held as an item of high value, not sitting on open shelves, but cared for by professional curators and conservators within climate-controlled stacks behind secured doors. The way it is classified, and the value accorded the map and the book that holds it reflect the high status of early New England’s histories and the explanatory value it is presumed to hold for the United States. A long history of that status and explanatory value is embedded within scholarship, both historical and literary.

We are not arguing that the item is not valuable or that early New England does not explain important aspects of the United States that emerged out of revolution, but that this context needs to be noted not assumed. The map is not a transparent representation of “New England” but an assertion about a place with different names, that was the homeland for Native peoples, had been claimed by settlers, and was deeply contested. For archivists and librarians, whether to acquire, how to classify, and when and how to make available such an item now raises questions about the privilege of colonial collections and who can access them. This volume and others like it in fact have deep patrimonial value for Indigenous peoples in New England, further nuancing questions of care, access, and stewardship.

Perhaps more obvious are materials that more starkly reflect how they were produced and collected in the context of violence. Records of enslavement, such as log books of slaving ships or plantation records show us in no uncertain terms that they were the work of enslavers – people who violently enslaved others, and whose records reflect their presumptions and practices, but also whose materials have been important for libraries to hold to allow a fuller understanding of this history. The same is true for records of the U.S. prison system, which until recently were the authoritative source for understanding the history of mass incarceration. Absent from collections were the individual voices and community stories of those directly impacted by the carceral state. Consider the issue of solitary confinement; records produced by the Federal Bureau of Prisons portrays a necessary punitive measure, but documents from incarcerated individuals as well as psychiatric and medical professionals point to torturous conditions that have a starkly deleterious impact on mental and physical health. The issues of power and privilege in the creation and preservation of rare materials are not limited to materials related to settler colonialism, slavery, or incarceration, but rather pervade all manner of materials that are now “archival.”

Surely there are so many areas where collaboration will be essential but for subjects of urgent attention right at our libraries now, namely colonialism and carceral collections. Without the nuanced background that these different fields and professional training provide, we risk missing out on key interventions or at least not advancing the work on these tender and complicated questions. We don’t need to read the daily news to know that the cultural and political stakes are high.

One path to mutual work may lie in simply more and fuller awareness of one another’s work. To this end, we have created through a set of projects we are involved with, a Zotero bibliography. It is a starting place, and we invite you to peruse and even contribute. For our own work, whenever possible, we bring together interdisciplinary groups — both in the traditional sense of including a variety of academic disciplines – and also in the purposeful sense of mixing together scholars, archivists, and librarians and often individuals working in public contexts. We have benefitted so much from our own collaborations, and we see this approach as a necessary start, though certainly not a final endpoint.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Critical Archives"

Dear both

Thanks very much for this.

You might be interested in a discussion of these themes coming from anthropology: ‘Anthropology In and Of the Archives: Possible Futures and Contingent Pasts. Archives as Anthropological Surrogates’. 2012. Annual Reviews in Anthropology 41, 461–80. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145721

There’s also an annotated bibliography:

‘Archives (revised version).’ In Oxford Bibliographies in Anthropology. Ed. John Jackson. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023. https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/display/document/obo-9780199766567/obo-9780199766567-0198.xml?rskey=jSOQm3&result=1&q=archives#firstMatch

You might be interested in my recent piece: Henchy, Judith. “Tracing a cosmopolitan subject: dislocation and haunting in the Southeast Asian archive.” In Browndorf, M., Pappas, E., & Arays, A. (Eds.). (2021). The collector and the collected: decolonizing area studies librarianship. Library Juice Press.