Peer review has a rich and storied history dating back centuries. Its roots can be traced to the early scientific academies and societies of the 17th century, where scholars came together to evaluate each other’s work. This paper suggests that peer review in some form existed even earlier. However, the term “peer review” and the process the way we know it today evolved much later and was not seen as a central part of science until the late 20th century.

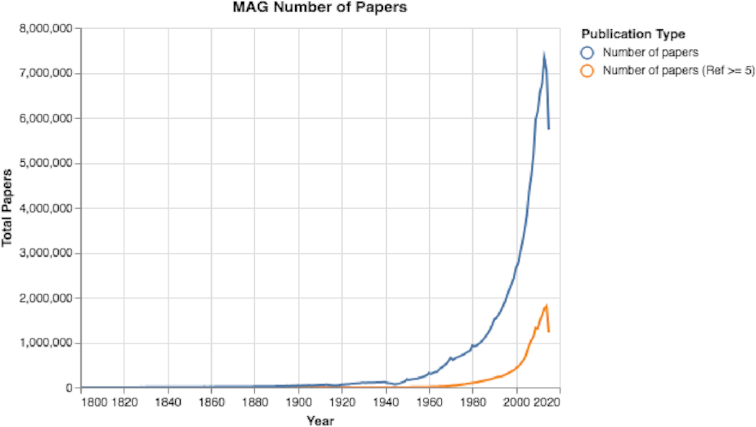

The academic environment has also transformed significantly, marked by a consistent increase in the volume of published papers.

Are there enough reviewers though to meet this demand? And is the peer review process efficient enough to handle the sheer volume of papers being published?

International research collaborations are also steadily increasing, having grown from 22% to 24% between 2015 and 2019, and we have also seen an increase in interdisciplinary collaborations. Are peer reviewers adept at grasping the cultural subtleties involved in reviewing such research? Furthermore, do they possess the expertise to evaluate interdisciplinary research domains?

The emergence of platforms like eLife and F1000, not to mention preprints, have ignited conversations about the fundamental nature of peer review. Some express concerns regarding research integrity, while others appreciate the accelerated publication timelines.

There are thus many differing views on the value that peer review adds to the publishing process. On one hand, there is conversation about peer review failing especially in doing what it is supposed to do, i.e., maintaining the quality and integrity of research and on the other there is evidence that peer review not only helps to improve the quality of the manuscript but also helps in selecting highly cited papers.

The Critics

“If peer review was a drug it would never be allowed onto the market,” said Drummond Rennie, deputy editor of the Journal Of the American Medical Association and the key figure behind the International Congresses of Peer Review held since 1989. According to him, peer review would fail to secure market entry due to the lack of convincing evidence supporting its benefits and a lot of evidence pointing to its shortcomings.

To add to this, Adam Mastroianni, in his article “The Rise and Fall of Peer Review,” questions why reviewers often overlook fundamental errors and blatant fraud. One reason is that they probably never look at the data underpinning the papers that they evaluate, which is exactly where the errors and fraudulent practices are most likely to surface. In fact, in his view, the introduction of the peer review system might have inadvertently encouraged questionable research practices. In a research context where you’re striving to publish a study and a reviewer requests modifications or additional investigations, it can introduce substantial pressure. This pressure may potentially result in adjustments to the study, such as data manipulation, the omission of unfavorable findings, or an extensive exploration of various aspects or conditions until a desired outcome is achieved, often at the expense of disregarding less favorable results.

Resonating these opinions about the peer review process, Fabio Casati, a computer science professor at the University of Trento with 20 patents to his name and the originator of a ‘liquid journal’ that eliminated prepublication peer review, also expresses the view that their research has revealed shortcomings in the traditional peer review system. According to Casati, numerous papers receive favorable evaluations from peer reviewers but ultimately have limited influence on their respective fields. Conversely, many papers with average ratings manage to make a substantial impact.

In addition to this, peer review has been criticized for the time it takes to review and publish a paper — sometimes more than a year. The costs involved are also very high. It is difficult to obtain data on the actual cost of peer review, mainly because reviewers often work without compensation. However, the opportunity cost is high, namely the considerable time spent on reviewing that could have been more productively utilized for activities such as conducting original research.

Also, peer review comments are not always consistent. Despite the common perception of peer review as a highly objective process for providing commentary on someone else’s work, it ultimately hinges on the reviewer’s subjective viewpoint, which can seldom achieve complete consistency. Just as people may have diverse opinions when rating or reviewing a movie, with one person loving it and another disliking it, peer review is no different in this regard. These inconsistencies in feedback can often prove perplexing for authors.

Peer review is also susceptible to status bias, where established authors receive more recognition for the work compared to lesser-known authors, regardless of their actual contributions to the study. Since we are discussing biases, we should not ignore experiences of non-native speakers of English as they strive to publish in international journals of their choice. Critics have also accused peer reviewers of forming assumptions about a paper’s quality based on the names or affiliations of the authors.

Lastly, there is a belief that peer review discourages the publication of negative results. However, if the research question is valid and the answer is present, the significance of the finding should not be contingent on whether it is positive or negative.

Has the peer review process become obsolete?

So, in light of all this criticism, let’s address the question “Has the peer review process become obsolete?” – the answer is a resounding no. It couldn’t be, considering its indispensable role — maintaining the quality and integrity of research.

Peer review’s significance lies in its role as a quality control mechanism for knowledge dissemination. It’s like a tea strainer. Imagine a cup of tea that hasn’t been strained. It would be difficult to drink it. In an era when information was scarce and often unreliable, peer review emerged as a means to ensure the accuracy and credibility of scientific discoveries. Much like the tea strainer, it sieves out the errors, the biases, and the unsubstantiated claims and leaves you a paper that can be readily consumed. However, just as a tea strainer may not catch every single stray leaf in your cup of tea, peer review might not identify every minor error or potential flaw in a research paper. Nevertheless, it significantly diminishes the likelihood of encountering papers riddled with inaccuracies or ethical concerns.

While the tools or methods employed may become obsolete with time, peer review’s underlying goal or purpose remains unchanged. Yes, the academic landscape will evolve further as technology advances, societal expectations change, and research practices adapt to new challenges. Hence, the peer review process too will need to evolve with the changing times.

This evolution requires a commitment to adapt, innovate, and learn from experiences. By embracing change, we can ensure that peer review remains a robust and trusted pillar of the academic and scientific enterprise for generations to come. In whatever form it exists, it needs to continue to serve its purpose of maintaining the quality and integrity of research. This peer review transformation will need to be conscious so that the impact is high.

The Peer Review Renaissance—what we should work toward

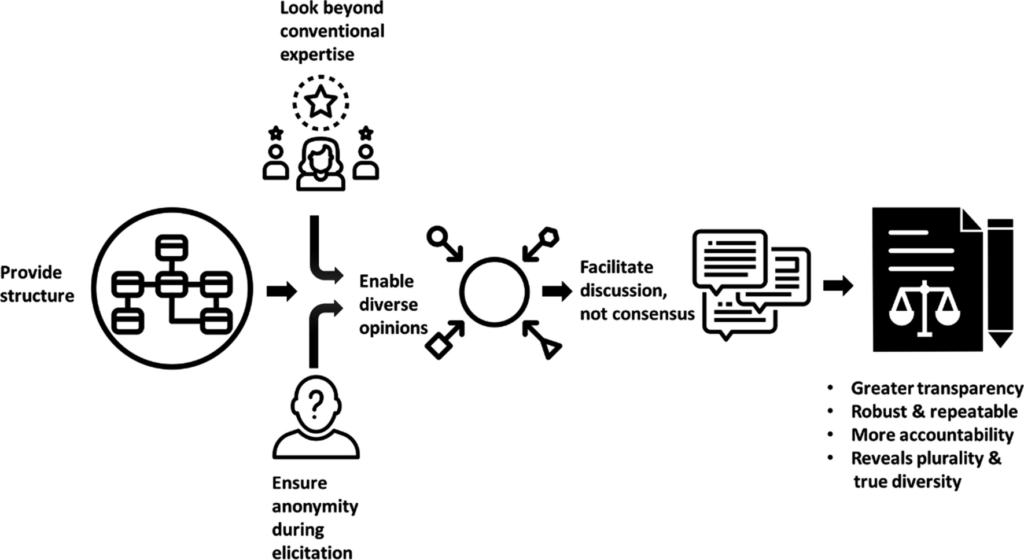

There is a lot being done to make peer review more transparent. But what we need is a process that is inclusive, diverse, and collaborative as well — a process that is designed to serve the purpose it is meant for.

For me in an ideal world, every researcher would get equal opportunities to peer review. We’d see an equal spread of peer reviewers in every country across the globe. Perhaps AI reviewer matching systems will enable this?

Moreover, researchers in Western countries find themselves in exceptionally high demand as reviewers for research papers. A survey conducted by IOP Publishing, encompassing over 1,200 researchers worldwide, reveals that even the most seasoned reviewers in Western nations express fatigue due to the sheer volume of review requests. Notably, the survey indicates that a substantial 40% of reviewers in Germany, the United States, and the United Kingdom believe they are inundated with review solicitations. In stark contrast, only 12% of Chinese reviewers report feeling overwhelmed by review requests, while 28% of Indian reviewers express that they have more time available for engaging in peer review activities. These statistics reflect on the lack of diversity in reviewer selection. How can we work toward a future where journal editorial boards would embrace a global and gender-inclusive approach?

This will not just give equal opportunities but will also allow for different perspectives, which will help improve the quality of papers.

An important consideration is to understand the ways academia can disrupt the traditional concept of expertise. The objective is to promote geographic and gender inclusivity, thereby expanding the talent pool to enable individuals to engage in reviewing and contributing to the field of science.

How can a combination of human expertise and AI make the peer review process more efficient? I envision a future where AI is not a threat or a cause for worry but a tool for enhancing efficiency.

What about post publication peer review? Will it come to replace peer review in its traditional form? This paper, proposes that with a sufficiently large group of post-publication readers providing feedback, the accuracy of review could surpass that of traditional peer review. The obvious question for such models is how to ensure that the review actually takes place rather than being left to volunteerism and chance.

Finally, how can authors and reviewers unite and work together as a team instead of being on opposite sides? How can reviewers have ongoing discussions and conversations with the author during the review process itself? And what measures can authors and reviewers take to harmonize their efforts with the common aim of refining the paper to its highest potential?

This peer review renaissance is not merely a destination but a journey of continual improvement. There will be a lot of failed experiments as the process evolves. But every experiment will take us one step closer to our goal of making the process more robust, efficient, diverse, and collaborative.

Discussion

5 Thoughts on "The Peer Review Renaissance: An Urgent Call for Transformation"

something to consider is also doing peer review from the earliest stages of research (e.g. starting from the conceptualization of a study/experiment).

back when i though i had this one brilliant idea, i whipped up a quick proof of concept so to speak, put it online and reached out to a couple of people in the field asking for their feedback. one person responded and even went so far as to schedule a video call and explained to me why they thought it was a bad idea. couple weeks later seeking a second opinion i presented the idea to a different person in the field (this time in person) and they tore my idea into pieces on the spot.

i thought that was great and saved everyone a lot of time and effort. like i could’ve collected more data, done an extensive study, written it up, submitted it to a journal — even get it published! — but by doing this sort of informal peer review at the earliest stage a bad idea was averted and i was able to focus on other ideas.

i suppose plenty of academics already do it in some way or other, but it would be beneficial to formalize the process — and reviewers would be more likely to volunteer their time and expertise if they’re not facing a 15-20 page dense behemoth of a paper.

I agree! Your experience highlights the significant benefits of early-stage peer review. Many academics tend to be hesitant to share their ideas in their infancy for fear of criticism, but your story shows how valuable constructive feedback can be in refining and redirecting research efforts. By creating a structured framework for this kind of peer review, researchers could receive guidance and insight that helps them shape their research in more meaningful and impactful ways. This proactive approach not only saves time and resources but also helps researchers avoid pursuing ideas that might not stand up to scrutiny or that are unlikely to contribute substantially to the field.

While this will definitely save a lot of heartache for authors and time for reviewers, the only flip side would probably be if the research were very sensitive, and the author did not want to put it out there for confidentiality reasons. In cases where research involves sensitive information or data that should not be disclosed prematurely, a solution could be to establish a secure, confidential platform for early-stage peer review. This way, researchers can maintain control over who has access to their ideas and data while still benefiting from valuable feedback. Striking a balance between openness and confidentiality is essential, and it’s a challenge that could perhaps be addressed in the formalization of this process.

This is a well-written, even-handed look at the situation. Did your research give any insight into how someone interested in peer review would go about lending a hand in the peer review process? Particularly someone new to scholarly publishing?

Thank you Josh. I am glad you enjoyed reading this. Although I didn’t specifically encounter this idea during my research for this article, I believe that everyone brings a fresh perspective to the table, whether they are newcomers to the world of scholarly publishing or seasoned veterans. As the saying goes, teaching is one of the best ways to learn. Therefore, providing feedback could potentially motivate early career researchers to surpass their current abilities and enhance their skills.

I sense that the industry is gradually progressing towards a more inclusive culture, with increased opportunities for researchers worldwide to participate in the review process. One effective approach could involve composing a letter of intent to the journal editor, in which individuals can share their interests and experiences, while expressing their desire to become reviewers. But before that, another feasible starting point might involve engaging in informal peer reviews for friends and peers before officially taking on the role of peer reviewer. As Sasa suggested in her comment to this article, informal early-stage reviews are probably already taking place informally. Such reviews can potentially empower those who are new to the industry, giving them the confidence to contribute to the formal peer review process in due time.

If there is a shortage of reviewers in a field, it is likely that the volume of publications in that field should not be expanding rapidly. This is the negative feedback that publishers should receive as a sign of slowing down. Continued expansion requires publishers to pay for an increase in reviewer resources: paying reviewers, spending money to train researchers to become reviewers, spending money to build the infrastructure to match reviewers, etc. I’m surprised the authors didn’t mention the option of paying reviewers at all. An important reason why reviewers are overwhelmed is that in most cases their contribution to peer review is unpaid work for commercial publishers. Publishers, despite benefiting from the unpaid work of reviewers, find that this limits their further unjustified expansion. I’m sure there will be publishers who change their peer review process with such insatiable motives.