As in any other system, trust in scholarly publishing is shaped by how actors interact with each other. These actors are mostly part of the inner core of the system, such as authors, editors, peer reviewers, publishers, and publishing infrastructure/service providers. In the outer core, we find researchers’ host institutions, including their libraries, indexing agencies, scholarly policymakers, research funders, and publishers’ societies as important actors directly supporting the inner core. And, outside the core is the area where research use takes place and research impact happens, which thus includes public and private sectors uptaking research, including businesses, practitioners, and public policymakers, and the general public at large.

We often talk about trust in the publishing system or in publishing processes; but it’s really the individuals playing specific roles to make the system or process work, that determine if it is trustworthy. To me trust in academic publishing is all about how a type of actor (e.g., publishers) is acting as per the expectations of the other actor types (e.g., authors). Since such expectations vary a lot from actor to actor, trust remains quite fluid, sometimes unpredictable, and always evolving over time. That’s why many of us may see the so called ‘predatory journals’ posing an obvious case of breaching the trust of authors, while big journals showing serious anomalies may remain uncategorized. While publishing fraudulent data is an abuse of trust, retraction of an article by a journal hardly gets recognized as restoring that trust. Double-anonymized peer review, which represents a strong sign of trust in the review process, also highlights the fact that reviewers can’t be trusted to be unbiased if they know the authors’ names, genders, or affiliations. Since there are no set standards, as in publishing ethics or in Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Accessibility, it is difficult to define, track, and measure trust in scholarly publishing. Nevertheless, let me give it a go using three examples.

Example 1: Delisted Journals — delayed actions, ignored justice

Fifty journals from well-known publishers were delisted from the Web of Science (WoS) by Clarivate in March 2023. Like many, I see this as an effort from the Clarivate’s side to reinforce clients’ trust in the WoS. But this case has two other trust issues. First, in that delisting announcement, Clarivate stated that another 450 journals were under scrutiny — 2 percent of WoS’s 24,000 peer-reviewed journals. During May-December 2023, 94 more journals were delisted by Clarivate. Of these, 36 journals faced delisting for not meeting one or more quality criteria upon re-evaluation, which is only 8 percent of all the journals stated to be under investigation. This sluggish progress in delisting of unqualified journals raises a question: Does Clarivate’s ‘slow’ pace of delisting mean that Clarivate is allowing these potentially low-quality journals to continue earning revenue by using their WoS affiliations and Impact Factors? I emphasize the word ‘slow’ because over the same eight-month period, 368 new journals (or on average 46 journals per month) were added to the Web of Science Core Collection.

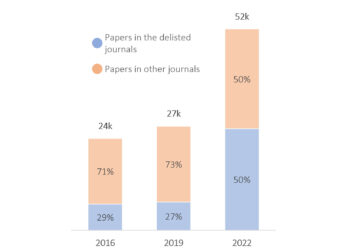

Of course, Clarivate’s delisting decisions hit some journals very hard, causing them to lose huge sums of revenue. But the second aspect of this case is that, despite having seen their trust breached, authors continue to publish in those delisted journals and other journals from the same publishers. And nobody is talking about the retrospective impact of this ‘Delisting-gate’. Over the years, authors paid millions of dollars in article processing charges (APCs), believing that these journals invested in quality to maintain their Impact Factors, which they failed to do so badly. I’ve yet to hear anyone talking about compensation for the authors’ scholarly damage.

Authors are so powerless in the publishing ecosystem that they can’t even challenge those entities who break their trust.

Example 2: APCs — trusting without transparency

Some journals charge up to 52 times more for their APCs than their sister journals from the same publisher. Open access (OA) and hybrid journals do not openly state exactly how their APCs are calculated to cover infrastructure building and maintenance costs, human resource expenses, R&D costs, communications and promotional expenses, the waivers/discounts offered to authors from Research4Life countries, costs incurred due to articles rejected after peer review, and management and overhead costs, for example. We also don’t know how much of an APC actually goes toward paying for a journal’s ‘brand’ and how much goes toward profit for the publisher.

We may estimate broad expense line items to a limited extent though. For example, the American Chemical Society (ACS) recently announced that they are going to allow green OA (i.e., allowing peer-reviewed manuscripts to be made openly accessible by authors putting them in a self-archived repository) and will charge $2,500 per manuscript as an Article Development Charge (ADC) for their hybrid journals. This amount is 56 percent of the Gold OA’s APC ($4,500) for the same journals. So, most of the article processing expense is associated with managing the peer-review process.

Despite an absence of transparency towards their clients (authors), authors still trust these journals, and pay the listed APCs without question.

Example 3: A case of deceptive journals

Scopus is one of the most trusted databases used for diverse purposes, such as running university rankings. Publishing an article in a Scopus-indexed journal is also an important criterion for academic staff recruitment, promotion, and annual evaluation; such articles would qualify for an APC-support from the host institutions; and even get considered for publication rewards. Such a high regard towards Scopus indicates academics’ and their institutions’ trust in Scopus for maintaining a quality database.

Research published by Anna Abalkina on November 27, 2023, however, shows that 67 journals in Scopus are hijacked journals. In these cases, hijackers are using an authentic journal’s identity to deceive potential authors. Scopus has failed to take proactive actions against such an ill deed, and remained slow in responding when complaints were made. Such a revelation is not new for this database. A 2021-article, for example, analyzed another publishing deception, predatory journals, in Scopus. That article was, however, retracted seven months after its publication in Springer’s Scientometrics. The reason for retraction was unreliability of some results due to some serious gaps in the methods used, which was realized only after a “post-publication peer review.” Whether correcting such a lapse in the methodology would still result in revealing Scopus’s weaknesses is a question yet to be answered. But given their significance, both of these peer-reviewed articles were quickly picked up by the commentators of reputed journals, namely Science and Nature, respectively, and attracted significant attention.

These studies may show that the academics’ confidence in Scopus that it will not tolerate any deceptive journals is apparently not fully being matched, but it does not seem to be weakening their trust in Scopus either. A recent quote from Stefan Tochev, CEO of MDPI highlights the complex relationship between journals and indexing agencies, and also between other actors of publishing ecosystems for that matter. Responding to news published on Retraction Watch that MDPI’s Sustainability was going through Scopus’s re-evaluation, Tochev noted, “While we acknowledge Scopus’ re-evaluation process for specific journals, it’s crucial to understand the scope and depth of our presence in this indexing database.” Scopus completed its re-evaluation of Sustainabilityand will continue to index the journal.

In the above examples, trust is directly linked with publishing integrity. But there are other dimensions of trust as well, such as transparency. That’s why we appreciate practices, such as transparent review by publishing a full peer review history of an article, or authors declaring use of AI in writing a manuscript. Equity could be a dimension of trust as well, where we would see journals making honest efforts to create opportunities for researchers lagging behind, for example, by applying consistent and clear waiver/discount rules for authors that need them.

In addition to the fluid aspect of trust, as mentioned at the beginning of this article, time is probably another crucial aspect of trust. Megajournals and their special issues, which have changed the face of scholarly publishing over the last few years, are now being criticized for breaching the trust by giving space to papermills. Non-peer-reviewed preprint servers, which took years to find their place in biological and medical sciences and were put between fast science and fake news are now part of many peer-reviewed journals’ workflows.

Despite our hopes that scientific research published in peer-reviewed journals is guiding our actions to fight global climate crisis, the president of the 28th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP28 in Dubai), Sultan Al Jaber of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) recently said something very concerning. He claimed in a live event on November 21, 2023 that there is “no science” indicating that a phase-out of fossil fuels is needed to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degree Celsius — a temperature threshold the world agreed in Paris in 2015 after a decades-long negotiation. Al Jaber, also the chief executive of the UAE’s state oil company, seemed to prioritize business and profit over science by undermining the world’s trust in him as the COP28 leader. Scholarly publishing industry leaders are often heavily criticized for their exorbitant profit margins. I wonder how much we can trust many of them in genuinely contributing to an equitable, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable scholarly publishing ecosystem with the conflict of interest that comes with prioritizing profit over integrity.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Trust in Scholarly Publishing"

I would like to join Peer Review Group.

Thanks