Today, the scholarly publishing sector is undergoing its second digital transformation. The first digital transformation saw a massive shift from paper to digital, but otherwise publishing retained many of the structures, workflows, incentives, and outputs that characterized the print era. A variety of shared infrastructure was developed to serve the needs of this first digital transformation. In this current second digital transformation, many of the structures, workflows, incentives, and outputs that characterized the print era are being revamped in favor of new approaches that bring tremendous opportunities, and also non-trivial risks, to scholarly communication. In a new report published today, Ithaka S+R reviews this strategic landscape as part of a broader analysis of the shared infrastructure that supports scholarly communication. Here, we provide an abbreviated summary of seven key strategic pillars of this second digital transformation.

Transitioning towards Service Provision

Scholarly publishing is in the midst of a substantial transition, from a model that was more centered on selection functions and editorial work, and towards a model in which funders and research producers seek services to distribute their research. In the most complete version of such a transition, one can imagine a publishing organization that serves essentially as a “white labeled” service provider for a research producer, but such a complete outcome may not be an end state we will see very often. Repository models are also another way to understand directionally where we might be headed. Today, publishing organizations fall into a variety of places along the spectrum of moving towards service provision, and the transition is occurring at a different pace in different parts of the sector.

There is a rich complexity of factors driving this transition. Broad changes in consumer models for content distribution and access have begun to influence scholarly publishers’ thinking about their own strategy. Open access is now a factor for a growing share of scholarly publications. And, business models that provide fairly direct rewards for growing the volume of articles have yielded a growing strategic focus on the author experience, provided an opportunity for new entrants into the marketplace, led to the publication of articles that might not otherwise have been solicited or accepted, and generated the need for new platforms, skill sets, and organizational structures.

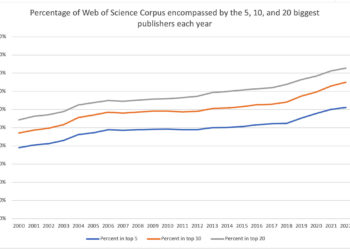

Consolidation and Competition

We are currently seeing two major forms of consolidation sweeping the marketplace for traditional publishing activities. The result is that some observers forecast a much more concentrated marketplace than we have today, with less than a dozen independent publishers and far less of a long tail remaining. At the same time, there are several important new market participants and vectors of competition, bringing renewed competitive vigor

Actual acquisitions of one publisher by another today appear to focus either on bringing scale to open activities or in non-STM fields. In addition, a growing number of independent societies have housed their publishing with some of the largest publishers, not only to gain access to services such as journal hosting and other infrastructure as well as to a global sales team, but increasingly to access the umbrella of global transformative agreements that large publishing houses have negotiated.

Recognizing these forces of consolidation, there are also new categories of competition. The transition to gold open access models created an opportunity for a new group of pure OA publishers, several of which experienced skyrocketing growth rates and took real market share. And, as several of the largest publishing organizations have sought to diversify their lines of business, a new category of competition has been developing in platform, analytics, and services businesses.

Humans and Machines

The longstanding purpose of scholarly communication — to support the dissemination of knowledge through human readership and authorship — is itself in transition as we move to a future where more and more creation and consumption of the scholarly record involves machine-to-machine communication and artificial intelligence.

The scholarly record may be atomizing into component elements such as data, code, and research methods, and a publication may over time be understood to incorporate the article identified as the version of record along with these other elements. The atomization of the scholarly record raises questions about assessing the quality, integrity, and impact of research at various levels beyond the version of record alone. How to bring the scholarly record into appropriate environments where text and data mining techniques can be utilized, or fitted together as parts of large language models, are among the dilemmas that publishing organizations face.

Generative AI grew in significance while we conducted this project, and we are conducting separate and additional analysis on this topic. Even so, there are clear considerations on the product and monetization side, as well as impacts regarding authorship, fraud, review, and integrity.

Scholarship as a Trusted Global Public Good

Scholarship is said to be a global public good insofar as increasing access to knowledge globally does not diminish the value of knowledge to anyone else, and it is expected to be high quality and trustworthy, generating broad public support for the expertise that it reflects. It has become clear in recent years how far away we are from the ideal.

Sadly, some of the challenges, particularly in terms of fraud and misconduct, come from within academia. Although serious, fraud and misconduct are probably not the primary drivers of growing public mistrust in science and scholarship. In the polarized political environment in the United States and other countries, higher education and scientific institutions are among the organizations that are no longer uniformly trusted. It is in the common interests of universities and publishing organizations to bolster public trust in scholarship and scholarly institutions.

Moreover, the contemporary expectation that all scholarship will be shared freely, as a kind of global public good, needs to be situated historically within the era of globalization beginning in the 1990s. The era of globalization has been winding down for several years, particularly given splits that have taken place with China and Russia. Even without the emerging national security and other regulatory limits to globalization, there are several different “geographies” for scholarly communication, for example the US, Latin America, Europe, and India, as well as China. Within each “geography,” there is a discrete package of funding models and levels and the associated policy that incentivizes and shapes scholarship and scholarly communications. Open access has reduced the barriers to distributing scholarship across “geographies,” but it has had less of an impact in integrating scholarship from across geographies into a single global and trustworthy scholarly record.

The Academic Reward System

The academic research system is organized to a very great degree around competition — for research positions, for grant funding, among universities, and so forth. This competitive system, reliant in certain disciplines to a great degree on citation metrics, establishes journal hierarchies (publishers in the case of books) that serve as measurements and signals of excellence.

The existing system reinforces the value of traditional publications. Various stakeholders have been calling for revisions to the traditional tenure and promotion process and indicators to build greater equity and flexibility in the rewarding system. This would require a direct assessment based on the scholarly content of an article rather than publication metrics at the journal- or article-level.

Efforts to incorporate other signals that might indicate the impact of research, for example media mentions and social media engagement, have developed, sometimes termed “altmetrics.” However, these have generally served to complement rather than replace traditional impact metrics.

Publishing Organizations

The publishing landscape remains rich with divergent organizational types despite the compact nature of the field. The field is dominated by several large publishers, many of whom have built their own underlying technological infrastructure to manage internal processes. Midsize and university presses can’t utilize the functionality of these systems, and the market isn’t robust enough to warrant extensive commercial investment and innovation for the needs of smaller publishing organizations.

Because serial publications command more market share than single titles, functionality for journals drives innovation more so than monographic publishing. STEM publications also command a larger market share, so their needs currently drive change more so than those of humanities or social science publishing.

Smaller, university, or mission-driven publishing organizations have various constraints that often force a competitive rather than collaborative environment. Branding, especially for university presses, is critical to their success in ways that inhibit consolidation.

Divergent Perspectives

In our work, we interviewed roughly 50 individuals, seeking divergent perspectives that could inform our work, and we were not disappointed. That said, today we do not find a major fissure between promoters of open access versus subscription models. And ultimately, we did not find so much a clear set of coherently differentiated schools of thought as we did a series of spectra on which perspectives varied significantly.

To take a few examples: In our interviews, a real tension emerged between those who believe that publishing should primarily be a truly open system that maximizes inclusive participation and those who believe that publishing should primarily be responsible for securing the boundaries of the scholarly record to ensure that it is validated and trustworthy. We heard several different perspectives on privacy and anonymity in terms of data practices. Several interviewees take a decidedly globalist perspective, believing that science cannot respect borders, while others expressed concerns that, whatever their own preferences, global science and scholarly communication may be fracturing. Several interviewees used the term “open science” but hold different definitions for the term.

Implications for Shared Infrastructure

This second digital transformation summarized above requires shared infrastructure that is fit for purpose, and the report we published today examines the needs for this shared infrastructure. Our report contains analysis of the existing infrastructure as well as the needs for new kinds of shared infrastructure, providing recommendations that address both immediate and long-term opportunities. Between the report’s narrative and these recommendations, we hope to have provided an analysis of the current landscape and projections on how to build on, protect, and improve the current shared infrastructure and opportunities for creating new infrastructure.

(Full disclosure, the authors of this post are employees of Ithaka S+R)

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "The Second Digital Transformation"

Sponsored by “STM Solutions and STM members, including the American Chemical Society, Elsevier, IEEE, Springer Nature, Taylor & Francis, and Wiley,” holds all the pertinent information you need. The funders and authors provide a defined strategic terrain that revolves solely around the market and each global company’s capacity to sustain and enhance profit margins. Curiously, the authors don’t appear to feel uneasy about presenting this as a ‘second digital transformation,’ overlooking the fact that the very market and its participants who fund this study have played a significant role in fostering skepticism towards science and the issues outlined in the report. The report is constrained by its sponsors and the narrow perspective of its authors, who only know the realms of the market, finances, rankings, and metrics. There seems to be a lack of ability to recognize the significance of shared infrastructure in contrast to proprietary systems that merely facilitate basic interoperability while upholding entry barriers.

Perhaps you missed this report by these same authors “Common Scholarly Communication Infrastructure Landscape Review” (https://sr.ithaka.org/publications/common-scholarly-communication-infrastructure-landscape-review/), suggesting perhaps more of a grasp of shared infrastructure than you grant them.

Hello, thanks for this report. In the Discovery, Collaboration, and Trust section there is an observation that “a key element of this gap is perceived to rest in the need for a secure digital identity for legitimate scholars”. I agree there is certainly a need for secure digital identity.

In Australia, the Australian Access Federation https://aaf.edu.au/ is a not-for-profit federal and member funded organisation that specifically works in the area of trust and identity for researchers through federated identities that establish trusted relationships between separate organisations. This solution is being embraced worldwide yet does not appear to have been surfaced in the report (unless I have missed it). Something to consider?