Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Camille Gamboa. Camille is Associate Vice President of Corporate Communications for Sage. Sage has recently launched Sage Policy Profiles, a free tool that let’s researchers discover where they have been cited in policy documents across the globe, visualize, and share what they find.

I recently sat down with Euan Adie, the founder and managing director of Overton, a company that allows users to discover how academic research is cited from a pool of more than 10 million policy documents. Euan’s journey – from his early days as a researcher in medical genetics to founding Altmetric (now part of Digital Science), and finally establishing Overton – reflects his – and our – fascination with improving and measuring research impact.

Could you describe your journey from the University of Edinburgh through Altmetric through to today?

I started out in medical genetics, doing computational biology, in a lab that was otherwise mostly bench science. There weren’t many of us doing just bioinformatics, so I ended up reading a lot of science blogs online and from there got interested in other ways of thinking about impact: how you might be focused on patients, or patents, or helping to build datasets or on spreading knowledge through blogs or seminars, and how none of it was captured by citations in journals.

That led to a job in 2007 at Nature for Timo Hannay who I think more than anybody was really pushing to explore how publishers could innovate to serve researchers more broadly, be it through preprints, shared reference management, living reviews or otherwise. It was an amazing environment. I eventually left to found Altmetric, which was a way of trying to collect alternative metrics — things beyond scholarly citations — as a way for researchers to prove that what they were doing was having a positive effect.

We’d done some policy citation tracking work at Altmetric and I’d always enjoyed it, so when the time came to move on I knew what I wanted to do next.

What inspired you to found Overton? What was your ultimate goal?

I was always really interested in what goes into policy: How many decisions are backed by evidence? Who is influencing how that research is found and interpreted? We might imagine government experts, think tanks and corporate lobbyists all somehow interacting – but how do you get involved as an academic? So one goal behind Overton is to make it all a bit more transparent.

If you ask as a researcher how you can best engage with policymakers, you’ll get a very unsatisfactory answer about having to be very patient but also ready to suddenly drop everything and put in lots of effort for potentially little return. All of which is correct but the other goal behind Overton was to try and make this process a little less painful for both sides.

I love that it’s an area full of tricky challenges. COVID showed most people that it was useful to have relevant experts contributing to big policy decisions, and laws like the Evidence Act in the US show that lawmakers want that, too. But how do you translate the nuanced answers we’re trained to give as academics into something more pragmatic that can actually be used by a policymaker? That’s an exciting question.

Could you describe the process of gathering and indexing this data? How do you ensure quality and accuracy?

It usually starts with a source – a government department, or an agency, or a think tank, really anybody in the policy sphere. We’ll add information about that source to the database, what country it is from, what kind of organization it is, that kind of thing, and then try to collect any publications that they might put online.

We check most sources for new documents once a week, though it can take much longer in some cases where publications are spread out across a very large government website.

When we see a new publication, we scan through the text looking for references to other policy documents or to scholarly research. We also look for people’s names: often contributions to policy are from a person having a phone conversation with a policymaker, or being on an expert panel, or submitting written evidence. It’s often not about the papers they produce but about their individual expertise.

Generally, we prefer accuracy over completeness — that is to say we’d rather the things we showed you were all correct at the expense of keeping back the ones we aren’t sure about — though we’ve been able to give users a bit more freedom to decide on this balance for themselves with Sage Policy Profiles.

What’s something that you’d like to make discoverable that’s currently out of reach, whether for technical or data collection obstacles?

Policy has its own negative results problem and I’d love more visibility into that.

If you’re the expert that tells a policymaker NOT to do something, then you’re not getting cited anywhere near the final legislation – you’ve clearly made an impact but it’s the “wrong type” of impact.

Similarly, in lots of places the early, exploratory stuff is the most politically risky and isn’t initially made public… so if it dies on the vine there’s no public record of why.

But by the same token, could fear of discovery reduce taking some creative leaps?

I think there are really interesting questions around where policymaking *shouldn’t* be open and transparent, not a million miles away from some of the arguments for and against open access in publishing years ago.

Policy is obviously relevant to the general public and they’re the ones paying for its research and production, so why not make the whole thing open? They want the best evidence to be used and the best experts to be consulted.

Unfortunately, they also don’t agree on who the best experts are — or if you should trust experts at all. There’s some great early work from Alexander Furnas at Northwestern on this, showing how little overlap there is in the science cited by Democrat-leaning vs Republican-leaning congressional committees and think tanks.

It’s easy for academics who’ve consulted on a controversial area – or had their work distorted and misused – to be targeted personally and end up a political football, like in the debates over school reopenings and mask mandates during COVID.

Could you provide some examples of how researchers have used their policy citation data?

A lot of users log in to help collect data for grant proposals or promotion and tenure committees, it’s a quick way to get some objective evidence that your work is being used in a policymaking context.

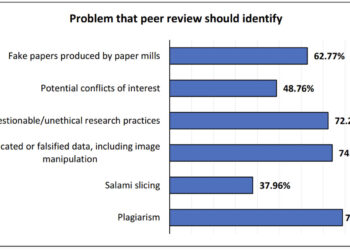

There’s also been a lot of published research that uses data for discovery or to help shine a light on how policymaking works. Two of my favorites look at how often retracted research ends up being cited in policy (distressingly often) and how governments used research when setting education policy during the pandemic.

Can you tell us a little bit about how academic publishers and librarians can use the tool?

We work with lots of academic libraries in three big areas: discovery, impact, and engagement. Discovery is all about researchers being able to search the full text of the more than 10 million policy documents we’ve collected and the curation work we do finding and adding new sources. Impact is being able to track citations and name mentions in policy at both the individual and institutional levels, and to be able to understand and export that data in a form that’s useful. Finally, engagement is around helping researchers who want to engage with policy to get started by finding what opportunities are currently active, which organizations they might want to approach and which of their peers might be open to collaborations.

Part of policy engagement is getting the right research to the right people at the right time, and I’d suggest publishers can and should play a useful role in that, be it proactively like Sage or The Lancet already do or more generally by finding receptive audiences for specific journals, commissioning or soliciting submissions from policy oriented academics, or monitoring how what they publish lines up with where the gaps in evidence required by policymakers are.

You’ve heard of Goodhart’s Law, right? The idea that once you create a measure, it ceases to become useful because it distorts behavior. How do we make sure that tools like Overton and Sage Policy Profiles don’t help to create new, unhelpful metrics?

It’s inevitable that they will! Unintentionally, not by themselves, and hopefully at a small scale, but it’s the flipside of the coin of policy citations becoming more available.

Don’t get me wrong, I think the data will do much more good than harm, but there’re always bad actors and unintended consequences.

Accepting that, I think the first key thing to do is to frame the data properly from the start: to be open about biases, caveats, to recognize that qualitative measures are more likely to be indicators — useful for direction of travel — than they are metrics.

The second is to properly engage with whoever is using the data as a measure: publishers have done this pretty succesfully (eventually) with DORA, I’d say, as have bibliometricians with the Leiden Manifesto. It’d be hard to sketch out the story of responsible metrics without mentioning them.

We have thoroughly enjoyed working with you to create the Sage Policy Profiles, and are excited that it is free-to-access. How is it different than the flagship Overton product?

We spent much more time on this app thinking about the user experience for individual researchers, partly after seeing how much Sage cares about the same thing, which I think has really paid off.

Being focused on one person’s data at a time was also new and actually opened up some opportunities that we couldn’t do otherwise, like being able to let the user curate their citations and mentions.

Thanks, Euan. Our hope there is not that it will become used by as many researchers as possible and help shift the research impact conversation, as you say, beyond scholarly citations.