Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Hélène Draux. Hélène is a Senior Data Scientist at Digital Science. Her specialties include gender analyses, geographic analyses, topic modeling, network analyses, and interactive visualizations.

This post is part of an ongoing series, the work of the Society for Scholarly Publishing’s Presidential Task Force aimed at prioritizing mental health awareness and support in the scholarly communications ecosystem. If you are interested in submitting a guest post for this series, please contact scholarlykitchen@sspnet.org.

As mental health concerns rise in global prominence, understanding the diverse landscape of research in this field becomes crucial for optimal funding and researcher support. Recent reports like “The Inequities of Mental Health Research” by the International Alliance of Mental Health Research Funders (IAMHRF) have attempted to map the global funding landscape. While valuable, this endeavor has relied on specialized features and expert interpretation, highlighting the need for more reproducible methods.

The multidisciplinary nature of mental health research, encompassing psychology, neuroscience, public health, social work, and psychiatry, inherently challenges efforts to define clear boundaries and scope. Consequently, even the broadest classification in Dimensions, ANZSRC Fields of Research (FoR), lacks a dedicated category for mental health research. Nonetheless, analyzing patterns within this vast body of publications holds significant potential, offering insights into research and funding trends, emerging topics, and key collaboration networks.

Several traditional and advanced bibliometric approaches offer pathways to chart the topography of mental health scholarship and address this knowledge mapping challenge. This analysis will be a two-part series; the first part will cover established methods, including pre-existing classifications like the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) MeSH and RCDC, as well as the UK HRCSthat offer established frameworks, while search strings and keyword analysis provide initial scoping. The second part, later this year, will delve deeper, utilizing topic modeling to uncover hidden thematic structures and employing bibliometric coupling to map intellectual connections through shared citations. Both elements of the analysis cover the five-year period, 2019 to 2023.

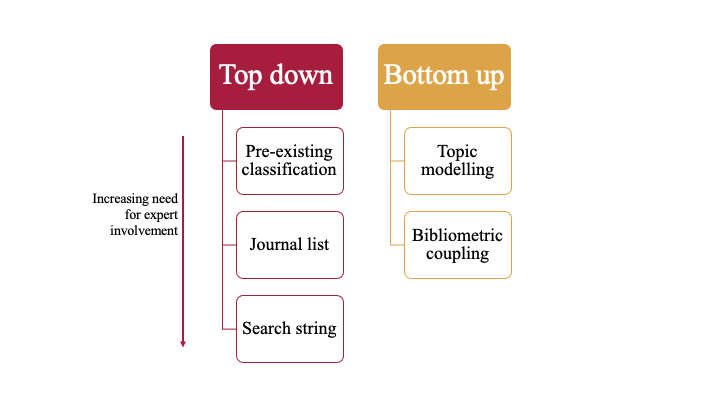

Bibliometric techniques for categorizing and analyzing academic literature can be broadly divided into top-down or bottom-up approaches. Top-down methodologies, used in this first part, start with predefined classification systems, which are often designed by subject experts, and then fit documents into these existing categories and codes. For instance, PubMed uses controlled vocabularies and taxonomies such as the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) to manually index publications under standardized terms, while some funders have created their own classifications. This expert-led approach allows for curation based on established ontologies, but can suffer from human biases and lags in updating new and emerging topics.

In contrast, bottom-up methods adopt a data-driven strategy by algorithmically detecting patterns and clusters within textual corpora. These unsupervised machine learning techniques include semantic analysis tools such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) for probabilistic topic modeling based on word co-occurrence frequencies. Network mapping of citation links and measuring bibliographic couplings can also uncover connections between documents without pre-set labels. Bottom-up analyses have the flexibility to uncover new topic spaces, but the clusters may be more difficult to interpret without qualitative verification.

Hybrid frameworks aim to obtain more granular insights by combining both manual and automated classification. For instance, pre-defined categories can provide a backbone structure for mapping new sub-topics that emerge from lexical analysis of full text contents. Bibliometric approaches stand to benefit from harnessing both human and machine intelligence to organize relevant knowledge domains such as the expansive mental health literature. The appropriate balance depends on use case goals and scope specifications when charting structural landscapes.

Existing classifications

The easiest way to delineate a field is to use pre-existing, top-down classifications. These classifications are created by bodies of interest, often government-related in the Anglo-Saxon world. There are 10 out-of-the-box classifications and a tagging thesaurus in dimensions.ai. Publications are assigned to the categories in each classification using an AI-based model created by the Dimensions team; the MeSH terms are from PubMed. Two of the 10 classifications cover mental health: the Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) and Health Research Classification System (HRCS), while the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) thesaurus has three relevant headings.

The RCDC System

The RCDC is a classification scheme used by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) to categorize its funding in medical research for public reporting required by the US Congress; it contains Research areas (for example, neurosciences), Conditions (for example, chronic pain), and Diseases (for example, asthma). There are three relevant categories: “Mental Health,” “Mental Illness,” and “Serious Mental Illness”. The last two are subcategories of the first.

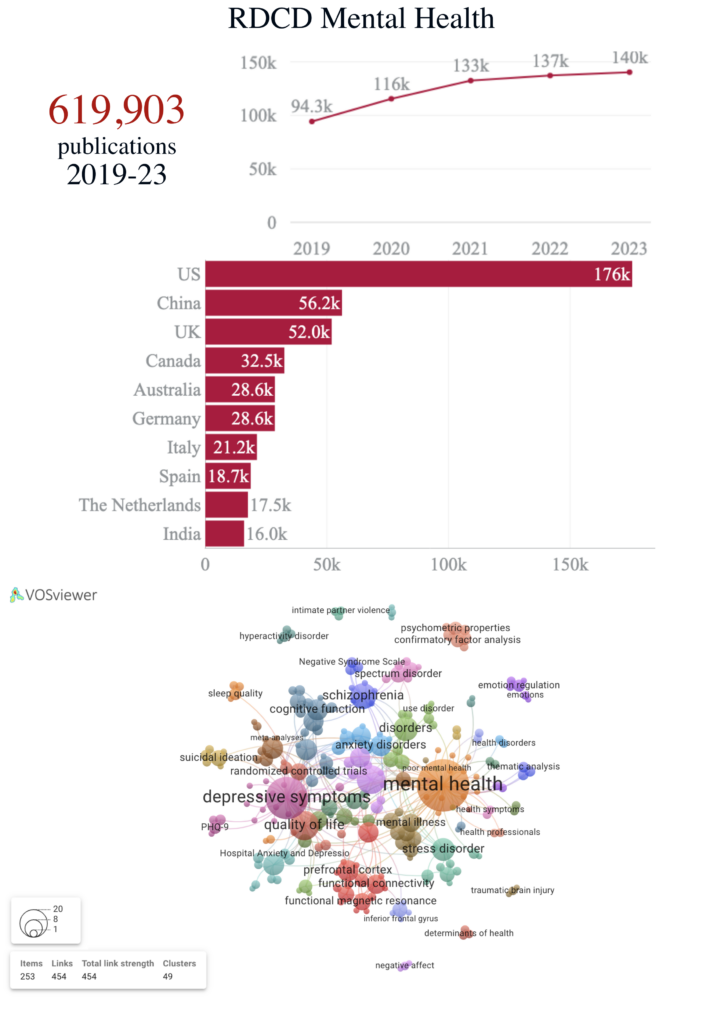

Between 2019 and 2023, 619,673 publications were published globally in the “Mental Health” category. Figure 2 illustrates the steady growth of publications in the RCDC “Mental Health” category over the past five years. While the rate of increase appears to have plateaued in 2021, it’s noteworthy that this coincides with a period of decline or stagnation in research outputs in most countries. This suggests that research activity within the RCDC “Mental Health” has remained relatively robust.

The leading 10 countries in RCDC Mental Health publications largely mirror those typically seen in research output. While the top three remain the same, China’s overall research output rivals the US. It publishes only half as many publications in health/psychology fields, and three times less in RCDC Mental Health specifically. Conversely, Japan, ranked fifth in health/psychology research, is absent from the top 10 in RCDC Mental Health.

The network at the bottom of Figure 2 shows the concepts used in the publications of the corpus, as well as their relationships. Each node, or bubble, represents a different concept or keyword found within these publications. The size of each node indicates the frequency of the concept within the dataset, while the lines connecting them, known as edges, illustrate the relationships and co-occurrences of concepts across different studies. The proximity of nodes suggests a stronger association or more frequent co-occurrence in the literature. For example, larger nodes like “mental health,” “depressive symptoms,” and “anxiety disorders” are central concepts that are strongly interconnected, indicating they are common and widely discussed topics within the RCDC representation of the field. The different colors represent clusters of closely related concepts, which can help identify sub-themes or focal areas within mental health research.

There is a clear trend towards examining the neurological underpinnings of mental health, as seen in the focus on brain areas and functions like the prefrontal cortex and functional connectivity. Furthermore, the intersection of mental health with critical social issues, such as intimate partner violence, points to a broader understanding of mental health that encompasses both biological and environmental factors. The network also emphasizes the importance of evidence-based approaches, with randomized controlled trials being a prominent method in the study of mental health interventions.

The HRCS

The Health Research Classification System (HRCS) is a classification system used by UK biomedical funders to classify their portfolio in health and research activity codes. One of the 20 Health Categories is “Mental Health.”

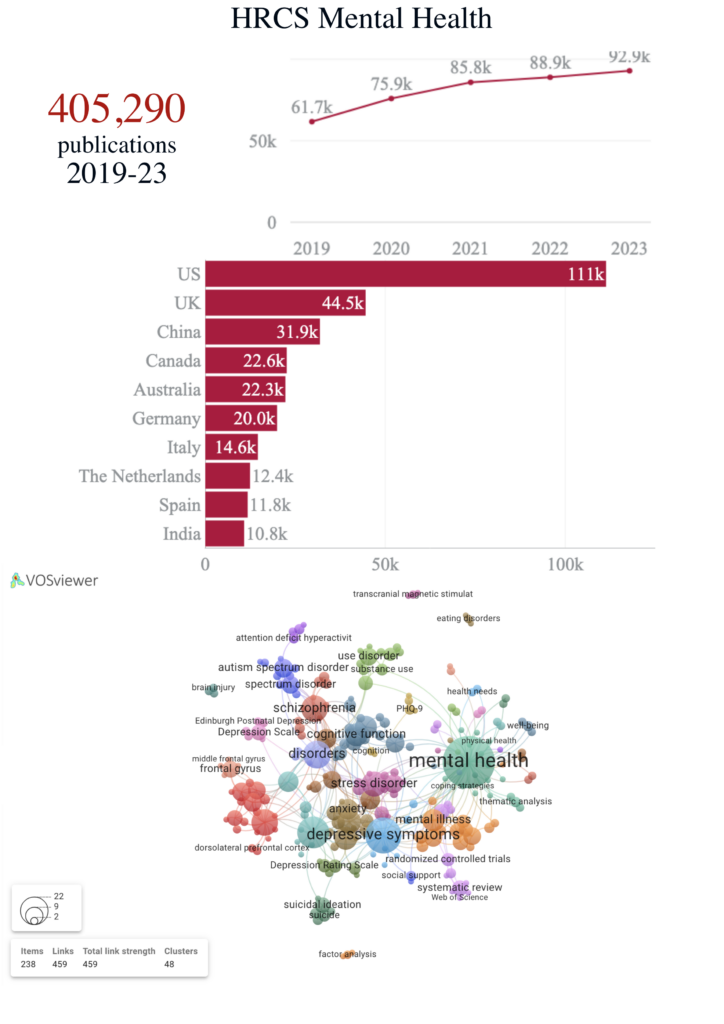

Between 2019 and 2023, 405,148 publications were published globally in the Mental Health category. A similar trend to RCDC can be observed over time for the HRCS Mental Health publications, with a slow increase. The top 10 countries in HRCS Mental Health research largely mirror those found in RCDC Mental Health. However, China dropped one position, falling behind the United Kingdom and publishing 3.5 times less than the United States.

The concept network for HRCS Mental Health also has a strong focus on specific mental health disorders such as “schizophrenia,” “autism spectrum disorder,” and “attention deficit hyperactivity,” which are less prominent in the RCDC-defined network. The inclusion of “eating disorders” and “transcranial magnetic stimulation” suggests a broader scope of interest, potentially indicating more diverse treatment modalities being explored within this body of research compared to the RCDC network.

The central node of “mental health” remains significant, maintaining its role as a core concept, with “depressive symptoms” and “anxiety” closely associated, similar to the previous network. However, there appears to be a greater emphasis on the biological aspects of mental health in the HRCS network, as seen in the prominent mention of brain regions like the “middle frontal gyrus” and “dorsolateral prefrontal cortex,” which are not as evident in the RCDC network. This points to a possibly more neuroscientific approach within the HRCS classification.

Overall, the HRCS network suggests a more varied and perhaps more mechanistic and evaluative approach to mental health research, with a notable inclusion of specific disorders and treatments not as prominent in the RCDC network.

MeSH

The Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) is the US National Library of Medicine (NLM) controlled vocabulary thesaurus used for indexing articles for MEDLINE (articles appearing in PubMed from other sources such as PubMed Central are not indexed via MeSH terms). There are 10 MeSH headings containing “Mental Health”:

- Mental Health Recovery

- Community Mental Health Centers

- National Institute of Mental Health (U.S.)

- School Mental Health Services

- United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

- Mental Health Associations

- Mental Health Teletherapy

- Mental Health

- Mental Health Services

- Community Mental Health Services

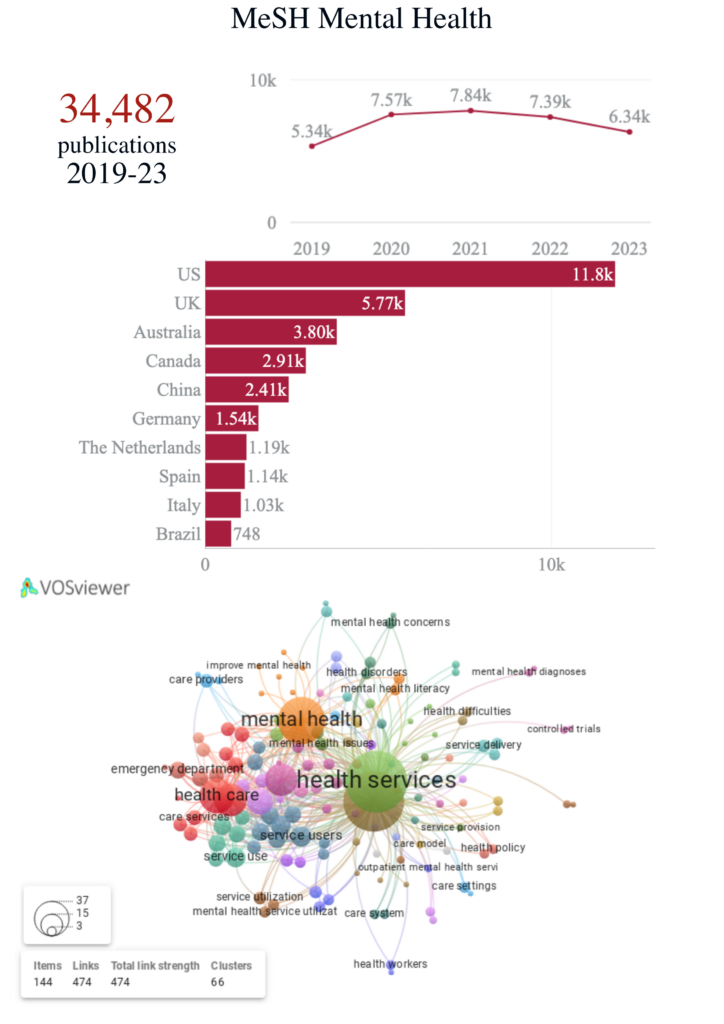

Between 2019 and 2023, 34,447 publications were published globally with the terms Mental Health and Mental Health Services. This much lower number is likely related to the MeSH terms being only available for MEDLINE indexed articles. The number of publications is also going down in 2022 and 2023. Brazil enters the top 10 leading countries.

The network based on the MeSH interpretation of mental health research focuses significantly on the service delivery aspect of mental health, a theme that was less pronounced in both the RCDC and HRCS interpretations. The central nodes of “mental health” and “health services” suggest that research in this area is deeply concerned with how mental health care is provided, accessed, and utilized.

Terms like “health system,” “care providers,” “service use,” and “healthcare system” indicate a robust investigation into the infrastructures of mental health care. There’s also an emphasis on the roles of various health workers, including “nurses” and “general practitioners,” showing an interest in the personnel dimension of mental health services.

Moreover, the presence of “severe mental illness,” “mental health problems,” and “psychological distress” alongside service-related terms reflects a concern with the practicalities of treating and supporting mental health at various levels of severity within the healthcare system.

Comparatively, the MeSH network seems to be less focused on the clinical and biological aspects, which were highlighted in the HRCS network, and more on the systemic, policy, and operational facets of mental health. This suggests a perspective of mental health research that is not only interested in conditions themselves but heavily oriented towards their management within the health service ecosystem.

Journals

Most journals tend to be topic focused, so an alternative to classifications is to take all articles from a specific set of journals. The selection requires some expertise, and therefore it is best to rely on an existing pre-curated list of journals. In the case of mental health, it is relatively easy to find such lists. For instance, Scimago categorizes its journals in subject areas, although it aggregates Psychiatry and Mental Health, so it is likely to encompass research that does not solely deal with mental health. It also excludes articles that are published in generalist journals (for example, Nature and Science). And finally, it is built on Scopus, which means there are fewer journals than those found in Dimensions.

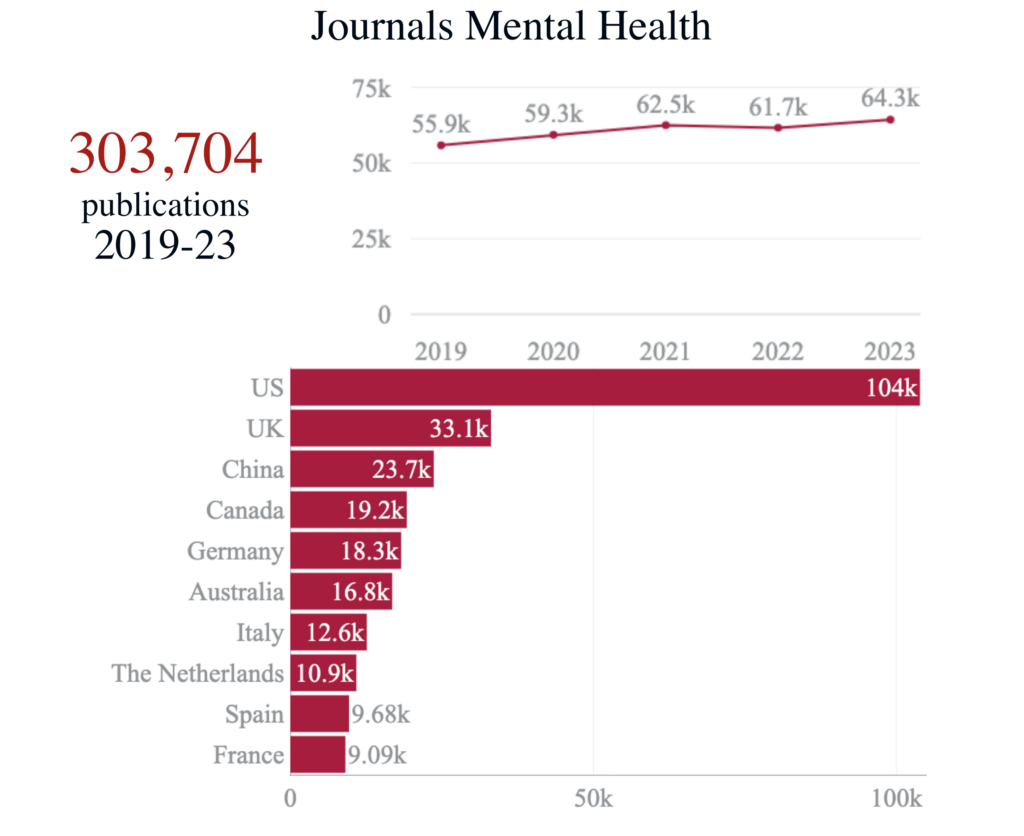

Between 2019 and 2023, 303,704 publications were published in the list of 562 journals identified in Dimensions.

Search strategy

Guo, Zhang, and Liu’s analysis of mental health and problems of children during the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, includes the search string they used in their study. I used the first part of their search string, related to mental health, and removed the terms such as “depressed” or “stress,” which are also used in different contexts. I cleaned out the terms that were ambiguous or redundant, and obtained:

(“mental health” OR “psychological” OR “psychiatry” OR “psychiatric” OR “emotional” OR “anxiety” OR “anxious” OR “anger” OR “angry” OR “loneliness” OR “lonely” OR “burnout” OR “insomnia” OR “worry” OR “frustration” OR “post-traumatic stress” OR “posttraumatic stress” OR “PTSD”)

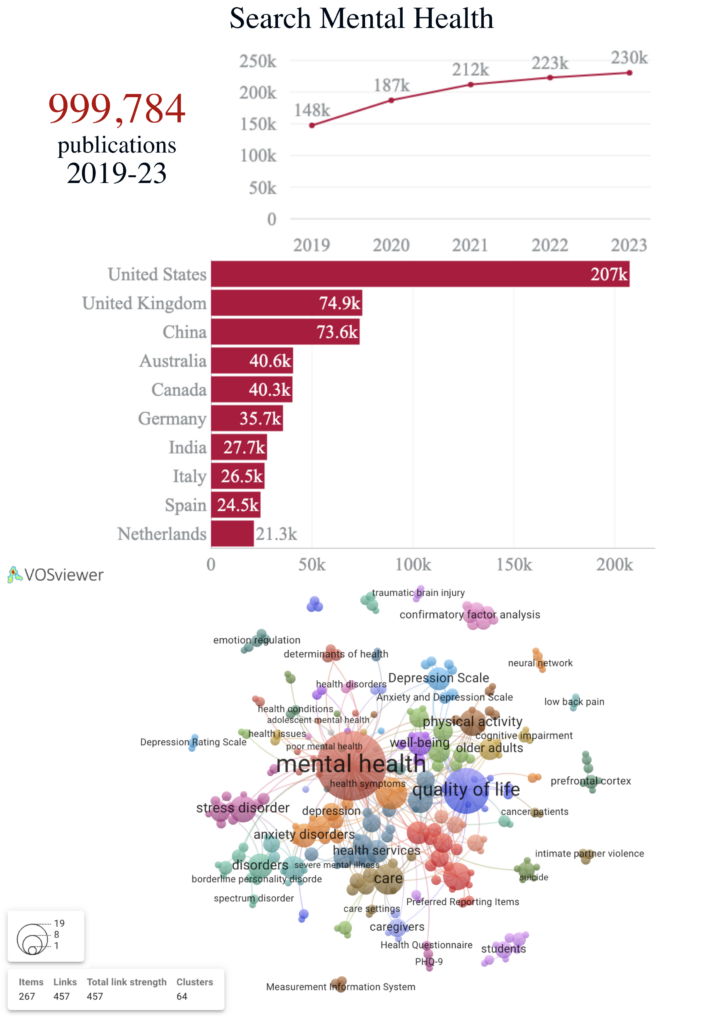

The search string gives 999,784 publications, which is the highest number of articles in these approaches. Overall, the number of publications in this corpus has steadily increased every year of the period. The 10 leading countries are similar to previous classifications, although the UK takes the second place, with China just behind.

On this last concept network, there is an emphasis on specific mental health conditions such as “anxiety disorders,” “stress disorder,” and “depression,” indicating detailed research interest in these areas. The inclusion of “quality of life” and “well-being” along with “physical activity” and “cognitive impairment” suggests a holistic approach to mental health, considering lifestyle and physical health factors as well. The terms “caregivers” and “students” indicate research attention to the social contexts and demographic specifics of mental health. Compared to previous networks, this one reflects a multifaceted perspective that spans clinical, social, and personal wellness dimensions, emphasizing the interplay between mental health and everyday life experiences.

Field comparison

The analysis generated five publication datasets using the top-down methodologies, from 34,447 to 1,209,327.

- RCDC: 619,903 publications

- HRCS: 405,290 publications

- MeSH: 34,482 publications

- Journals: 303,682 publications

- Search string: 999,784 publications

Each approach has inherent limitations in precisely delineating the field of mental health research, as most experts would disagree with the precise boundaries of any research field. Therefore, each will come with its own biases. The ANZSRC Fields of Research (FoR) classification, despite not having a mental health research category, helps here to identify the type of bias that is introduced with each approach.

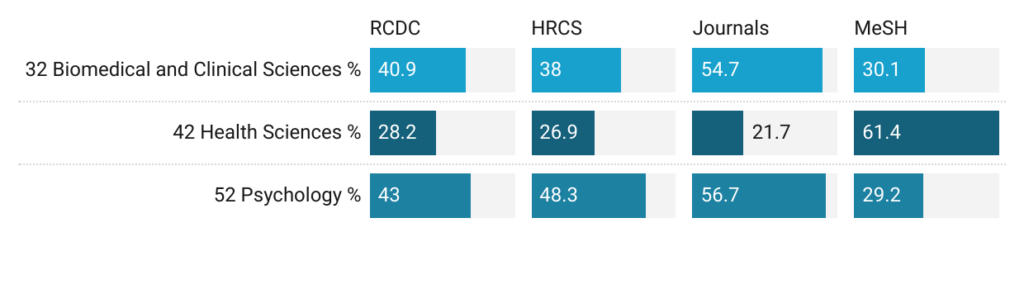

Figure 7 below shows the distribution of the four first approaches in the top three FoR of interest: 32 Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, 42 Health Sciences, and 52 Psychology. Each publication can have more than one FoR, so the percentages add up to more than 100%. RCDC and HRCS, which had the highest numbers of the pre-existing classifications, have relatively similar results, although the HRCS has a higher percentage of 52 Psychology publications and a little less in the remaining two. The journals would exclude many of the 42 Health Sciences publications, which are likely published in less specialized journals, and the MeSH terms, already restricted in terms of number, give a very large representation to 42 Health Sciences.

Conclusion

In this article, we have examined different methodologies to map mental health research, showing how contrasting yet complementary perspectives emerge. Top-down classifications like RCDC, HRCS, and MeSH provide frameworks reflecting established expertise, central issues, and the current state of the field, with a focus on clinical disorders and service delivery. Meanwhile, the search string method casts a wider net, capturing a more holistic view spanning from clinical conditions to societal impacts and well-being.

The analysis shows there is no one approach to classifying mental health research, but each methodology provides a unique lens. Expert-driven RCDC and HRCS frameworks gravitate towards a traditional, clinically and biologically rooted scope of mental health, while MeSH adds a layer emphasizing service delivery. In contrast, the search string approach encompasses a broader, more inclusive view, reflecting the evolving nature of mental health research.

Our exploration underscores the need to consider methodological frameworks when interpreting bibliometric analyses in mental health research. The choice of methodology not only shapes the dataset but also reflects inherent biases and focus areas. As we await insights from topic modeling and coupling, it becomes clear that mental health research is as complex as the human mind itself. By utilizing various bibliometric tools, we can better understand this complexity, ultimately contributing to more informed decisions in funding, policy, and research direction in the vital domain of mental health.