It’s now ten years since the Joint Information Systems Committee (Jisc) in the UK launched its first “transitional agreement” (TA) with Springer Nature. Since then, Jisc has negotiated and/or renewed 75 TAs with 47 publishers. (A note on terminology: I am using “transitional agreement” as this is the term used by Jisc. These are also referred to as “transformative agreements” – though, as we shall see, it’s arguable whether they have transformed anything. See my fellow Chef Lisa Hinchliffe’s primer if anyone needs a recap.) Jisc recently undertook and published a full review of TAs to understand how effective they have been in delivering an OA transition, to explore the impact of TAs globally, and to assess whether they have achieved the UK’s goals (see executive summary here; full report here).

The UK, like all countries, has its own specific history with the transition to OA and it’s important to note that it was sent down this path early on with the publication of the Finch Report in 2012. This recommended “publication in open access or hybrid journals, funded by APCs [article processing charges], as the main vehicle for the publication of [publicly funded] research” and was seen by some, even then, as a successful case of lobbying by the largest publishers. Nonetheless, we have collectively been sold TAs as a sustainable mechanism for transition to full OA, and so it’s worth diving into the Jisc report as a case study.

Have TAs achieved the UK HE sector’s requirements?

The picture that emerges from Jisc’s analysis is nuanced and complicated. There have certainly been positive developments and successes, including the following (all data is taken from the report):

- The global proportion of OA articles published has increased from 21% in 2014 to 46% in 2022. TAs have helped the UK to transition faster than the global rate with 50% of articles published OA in 2022.

- TAs have reduced and constrained costs at sector level. Jisc estimates that by 2022, HE institutions avoided costs of £42m through TA agreements. TAs have also enabled a broader section of researchers to publish their work openly.

But there have clearly been a set of less positive outcomes, such as:

- The UK’s proportion of hybrid is more than double the global average at 21% (compared with 10% globally), with a concurrent steady decline in Green (again, a more exaggerated version of the global trend). Rather than encouraging more diversity in publishing venues, TAs have helped to entrench hybrid with the biggest publishers.

- In recent years (2021 and 2022) there has been a resurgence in (or at least, retention of) Closed articles.Despite the growth in OA output, across the 38 publishers studied for the report 61% of their content was still closed.

- There are significant concerns with the longer term sustainability of APC-based models based on both accelerating costs coupled with the severe challenges faced by UK HE.

Based on the journal flipping rates observed between 2018 – 2022 it would take at least 70 years for the big five publishers to flip their TA titles to OA.

Most important is the question of whether TAs deliver on their promise of their name to be transitional and transformative. Overall, the rate of journal “flipping” is low (with the exception of some smaller publishers). Most shocking, if not entirely unsurprising, to me was the following finding: based on the journal flipping rates observed between 2018 – 2022 it would take at least 70 years for the big five publishers to flip their TA titles to OA. (In recognition of the slowness of this transition, cOAlition S booted 1,589 journals from its transition program last year.)

And while these data and conclusions are from the UK, it’s worth noting that similar analyses elsewhere have come to the same conclusions. Plan S’s Annual Review 2023 is entirely aligned with Jisc’s findings: Gold is the primary route to OA, Hybrid is growing thanks to TAs, and Green is in decline. (It remains to be seen whether cOAlition S’s decision to cease funding TAs at the end of this year will impact these trends.) A report last year from the Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions noted the risk of “getting stuck in a permanent transformation that favors large commercial publishers”. And a recent analysis based on agreements from the ESAC Registry also found that the primary shift was from closed to hybrid journals, with as yet little evidence that this would lead to “flipping the system”.

The failure of an APC-based approach

This is where I should be clear that I’m moving to my analysis and interpretation, not that of Jisc. I have always been skeptical about TAs, but I think that the real culprit is not so much the TA itself but the underlying payment model: the APC. Current models, including TAs, built on article publication are incompatible with an ecosystem founded on equitable Open Science principles in part because they further embed the article as the unit of value. This creates an article growth economy which exacerbates both existing pressure on researchers and the peer review system, and also creates a clear incentive for publishers to push for article growth in order to increase profit. (And yes, this in turn has contributed to the research integrity challenges we’re all battling. I’m not going to cover those fully here but suffice to say that the current difficulties at publishers who’ve grown rapidly through this model underlines its fragility.)

A second significant issue with TAs and APCs is the administrative burden. The Jisc report notes the importance of their centrally managed system for scaling OA but notes that the administrative burden still persists. The difference in TAs across publishers makes managing them resource-intensive and requires specialist staff. With library budgeting and negotiating still heavily linked to the legacy of APCs and assessed by cost per article (especially in Europe), it’s that much harder for libraries and consortia to adapt to newer and more inclusive models.

Taking a step back, reading this report reminded me of many posts and articles I’ve read over the years identifying the potential unintended consequences of how we’re managing the OA transition. I wrote one of those myself five years ago and it’s interesting to reflect back on my three primary concerns then in light of where we now find ourselves:

Many societies have felt the need to be under the “safe umbrella” of a larger publisher; market consolidation continues with the acquisition of smaller publishers, and the biggest five continue to dominate output.

The increased “marketization” of the scholarly record: My concern was that TAs “run the risk of locking in the high cost of subscriptions into an open future and of reinforcing the market dominance of the biggest players as subscription funds simply flow in full to new deal models”. I’d argue that this is exactly what we’ve seen: many societies have felt the need to be under the “safe umbrella” of a larger publisher; market consolidation continues with the acquisition of smaller publishers (F1000, PeerJ and more), and, as the Jisc report makes concrete, the biggest five continue to dominate output.

Researchers remain disengaged: Neither mandates nor TAs have changed this (the Jisc report also finds that author behaviors haven’t changed). And in fact, TAs have made it far easier for authors to comply with OA mandates without the friction of individual APCs. While there is undoubtedly a positive aspect to this, TAs are generally negotiated with the bigger publishers and so serve to entrench traditional author behavior without any need for authors to confront concerns such as affordability or equity.

Hardwiring the exclusion of research produced in the Global South: As Gold OA has taken hold as the dominant model, the inbuilt inequities have exploded exponentially, shutting out large communities – especially in the Global South. Waivers have emerged as a solution but not only are these unsustainable for at least small and mid-size publishers – including PLOS – but they fail to meet the equity standard. Simply put, they do not address the systemic structures that lead authors to need waivers in the first place. Waivers themselves are structured to ask those most in need of systemic change to jump through hoops that more privileged communities never see.

If not TAs, then what?

If TAs seem more permanent than transitional and don’t appear to be delivering a transformation any time soon, how should libraries respond? Unsurprisingly given its analysis, Jisc concludes that it’s imperative to find new ways to speed the transition that TAs haven’t delivered. In addition, they recommend:

- Alignment on additional indicators that demonstrate a commitment to equity, including support for non-APC models.

- Using the report’s conclusions and other indicators when deciding where to invest – and ensuring that those investments deliver on key goals such as reducing paywalls and increasing equity.

- Divestment from underperforming TAs to fund the above.

Those are all good suggestions, but I’d argue that we need a strategic focus on the long game here. As was noted during a panel discussion of the report at the recent RLUK meeting, the combination of the report’s findings with the serious financial challenges in the UK HE sector makes this the right time to reach for much bolder change.

As libraries grapple with that, I’d like to offer two core principles to keep in mind.

The first is to vote your values. Libraries are key partners in advocating for a shift from commercial control of scholarly communication to models that are better aligned with the core values of science. And while advocacy is important, it’s not enough. As the Jisc report concludes, it’s essential for libraries (and others) to invest in ways that align with their goals and values. One bold example of this is the MIT Libraries who have now been out of contract with Elsevier for four years and are preparing to reinvest the significant savings in line with the goals of the MIT Framework. For many libraries, this kind of decision isn’t easy (or even possible) to make. Any savings would be rapidly recouped by the Administration – or there simply isn’t sufficient institutional support. (It’s worth noting that a key reason for MIT’s success is the years of hard work of coalition building across both administration and faculty.) The librarians interviewed during the RLUK panel discussion echoed both of these themes: the need to rethink engagement with key stakeholders, especially researchers; and to expand the focus from OA to open science, equity, and affordability.

The second is to play through all of the potential consequences. This is something our industry isn’t very good at and we’re today living with the consequences of our failures in this area. I include my own organization in this – back when PLOS was launched and focused in the biomedical sciences where large grants were common, charging authors a fee to publish seemed fair and reasonable if it meant that anyone could read and reuse the paper. But we failed to anticipate how successful APCs would become, how commercial publishers would exploit this space, and how inequitable they would become. In a similar vein, there is a risk under the “refreshed” Gates Foundation policy that, without established alternatives, their grantees will revert to publishing their research behind paywalls. That’s why the work PLOS is doing with the working group we established with cOAlition S and Jisc is important to facilitate discussions with relevant stakeholders to try to drive change across the industry.

Of course, the responsibility doesn’t only fall to libraries. I’ve often argued that publishers have more agency than we’d like to admit and that while we can’t deliver broad systems change on our own, we can point the way and do a lot to halt further deterioration. We do, after all, have some culpability for getting us to this point.

We must pull back from the current focus on relentless growth of article output to maintain and grow profits. It’s bad for science and for researchers.

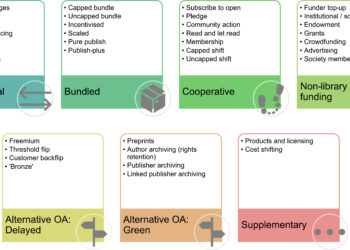

As a starting point, we must pull back from the current focus on relentless growth of article output to maintain and grow profits. It’s bad for science and for researchers. We’re not solely responsible for the article’s place as the currency of scientific productivity but we can stop fueling the fire. It adds to pressure on scientists and the peer review system and has given rise to the proliferation of low quality and predatory journals. While I think that this is entirely plausible right now at most, if not all, larger publishers, the shift to OA has been more challenging for smaller publishers, especially societies. Yet arguably the almost exclusive focus on the APC model is what’s making this much harder. There are a growing number of better suited alternatives (helpfully classified here by Tasha Mellins-Cohen), alongside opportunities for at least some societies to build new revenue streams (such as monetizing existing content in new ways).

In the longer term, we need to be thinking about much bigger transformations ahead. AI is going to fundamentally change how research is conducted and so we should expect similar shifts in how research is read and shared. The old paradigm developed decades ago based on print won’t survive this. Changes in the research lifecycle will accelerate the need for a more flexible system focused on a broader series of research outputs, appropriately shared and assessed at different points in the lifecycle. And I don’t think that unit-based pricing is even a feasible option to support this future.

I know that many of my colleagues share many of my frustrations – and have done for years. And yet the rate of true innovation in scholarly publishing remains pretty low. Transitional/transformative agreements were supposed to be just that, yet (as the Jisc report also recognizes), most publishers have done little to articulate what a “transformed” world looks like. It’s time for us to clearly articulate how we’re going to meet the demands of the future, along with a roadmap to get there.

Discussion

27 Thoughts on "Transitional Agreements Aren’t Working: What Comes Next?"

The OA movement spent over a decade spinning its wheels until the idea of read and publish agreements gained traction as a viable method of transition. At the time, those who pointed out the concerns about perverse incentives and inequities for authors were shouted down as naysayers. Now, those same concerns are de rigeur. Maybe “play through all of the potential consequences” should include “listen to your critics”.

If the scholarly communication brain trust has not come up with something better than read and publish agreements in twenty years, I am not sure we should expect something better in the next twenty. But maybe AI will help. Yes, that’s it.

exactly, Anonymous. My beat is the pathway to and land of unintended consequences. Its also a lot like Dorothy on the Yellow Brick Rd, except we dont have Ruby Slippers and our comraderie could improve….if, like the lion, tin man, scarecrow with Dorothy, we are in it together…its not a transactional deal to get a ride home….

I’m so puzzled every time I see a claim that TAs aren’t working. Especially when made alongside data points like: “The global proportion of OA articles published has increased from 21% in 2014 to 46% in 2022. TAs have helped the UK to transition faster than the global rate with 50% of articles published OA in 2022.” and “TAs have reduced and constrained costs at sector level.” How much more success was Jisc (or others) expecting in a decade?

I suppose it depends on what your goals are. The Jisc report analyzes whether or not TAs have met the goals of the UK HE sector, as defined post-Finch at the beginning of this process. While some of those goals have been met, some more fundamental ones (that TAs are a temporary transition route to a fully OA system) are clearly nowhere near making the progress they imagined. Yes, it’s only been a decade, but is it reasonable to expect 70 years for this transition?!

I still come back to the question of what they were expecting re timeline. What analysis had they done to predict what the transition time would be for a full flip accounting for TA offering/uptake? Only then could we know if it has fallen short? We might not like a 70 year timeline for a full transition but that doesn’t mean it isn’t reasonable given the level of offering/uptake of TAs?

The problem is the escalation in APC that have accompanied the TAs.

Commercial publishers are exactly that – commercial. To expect them to change their business model in the absence of any commercial imperative to do so would fly in the face of everything we know about how commerce works. I spent years trying to persuade members of the society whose journals I managed to publish with us rather than with commercial journals (with higher impact factors), without success. Unless the author community puts its publications where its mouth is, the grip of the commercial publishers will only strengthen. I would argue that, in the absence of a change in author behaviour, the current situation was entirely predictable and was, indeed, predicted by voices that were shouted down at the time.

I agree with many of your points, Robin (and was indeed one of those voices expressing concern when we started down this route). But I think our current predicament is a little more complex. Publishers – including the large commercials – “sold” libraries TAs as a temporary, transitional route to OA and they haven’t delivered on that. I agree with you about the motivations, but it’s also understandable that some funders and libraries feel that this has been a bad faith effort on their part.

My funder (a CoalitionS member, but severely underfunded) requires OA even after my contract with them has ended. This is outrageous – especially for ECRs in between jobs. CoalitionS and all the initiatives around OA have only succeeded in one thing – that the big five get even more money, not only from libraries but now also from grants.

Maja, I think you’re highlighting exactly some of the problems that I – and Jisc – are drawing attention to. One of those is very much about the inequities of the current system. In the UK experience, use of block grants to support TAs has expanded access to OA options but, as you say, this is too often focused on the bigger publishers. In my view, the APC business model underlies these challenges and we need to get serious about replacing it.

Great post. I too read the Jisc report with great interest and was not at all surprised to see that Gold OA was on the rise. All of this was very predictable and concerns were raised as far back as when PLOS launched PLOS One, to be honest. But alas, we move forward. On the cusp of the US government asserting that grantees must make the journal peer reviewed and accepted papers free with zero embargo, more and more journals will actually flip to OA (I predict in way less than 70 years) and it will be under predominantly Gold OA models.

I also watch with interest what MIT Press has done, but it is not scalable and I assume MIT is not at all dependent on MIT Press being a revenue generator.

I agree with Alison that TAs were billed as a temporary transition. But to what? More Gold OA?

Incidentally, Jisc told me that our 5 journals were not worth the administrative burden of setting up a TA. They said my choices were to allow authors to share accepted papers with zero embargo or not receive papers from UK cancer researchers. In spite of no TA and no allowance to share without an embargo, we still publish UK research via the Gold OA options.

The horse has left the barn.

Thanks, Angela. I agree that much of this was inevitable as the APC model really took off – and when it became clear that it was possible to run a profitable business this way. And while the current iteration of new models – whether MIT, PLOS or others – may not be fully scaleable, I don’t think we’ll ever figure out what could scale sustainably unless we try new things. That said, I share what I think are similar frustrations, notably the lack of coordination between key stakeholders. Too many of us act in the interests of our organization/stakeholder group without really thinking through the systems impact. If we could solve that one, we’d really be getting somewhere.

Thanks for the call to action Alison! I couldn’t agree more about the need to do more scenario-planning to think through the potential consequences of OA business models. While TAs have benefitted large for-profit publishers, they’ve also been a helpful tool for OA transition for publishers with programs where there isn’t much APC funding. However, one of the biggest unintended consequences of TAs has been moving the barrier to access to a barrier to publication. I wrote about this in the Scholarly Kitchen here (https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2021/10/20/guest-post-transforming-the-transformative-agreement/). Years have gone by now since I wrote this post and its been heartening to see the rise of models like S2O and the interest in Diamond OA but you’re right that there needs to be more experimentation to actually evolve and innovate on TAs (or institutional OA models) in order to deliver more fully on the transition to open.

Brigitte, you’re right that TAs have been a genuinely useful tool for some small and mid-size publishers – and societies – enabling what would otherwise have been a challenging transition. I know that CUP is one of these – and Jisc acknowledges these publishers in their report. It’s good to see other models such as S20 and Diamond gaining traction (though I do worry about the sustainability of Diamond over the long run). Another society publisher was telling me that their decision to focus on their community’s needs had led them to focus on Green and Diamond which is working for both them and their library customers. The big question is still how we scale enough of this to tip the system.

Transitional agreements have not been totally effective in delivering an open access (OA) transition. Agreed, and it was unsurprising. Now do the real aims.

We were assured by philosophers of OA that the movement was about science: It would help fix the problems of social inequality allegedly caused by restricting access to academic research.

With OA making articles free to read, taxpayers would now own the research they paid for. What have taxpayers done with that access?

OA was supposed to be especially impactful in developing countries. Has health equity been improved? Have economically disadvantaged researchers made important contributions to science because of OA?

What important pieces of scientific knowledge have been produced that would not have existed but for OA?

A really good post. But please, when you’re discussing scholarly publishing/research in general, don’t refer to it as ‘science’ (including ‘open science’). Researchers and publishers in the humanities are also affected by these issues.

yes, and…what are the ramifications? share your voice because it does add to the chorus

Any journal that flips to OA will need to publish more papers if it hopes to maintain profitably or simply break even. Or instead of being a money-making enterprise it will need to be subsidized by a society or some organization which could stress the society to the breaking point. So when Journal X at the top rejects only 50% of the articles coming to it and not 80% what happens to the journals who received those rejections? And so on and so on. Journals will fold, societies will fold and many jobs will be lost – all unintended consequences, though some people did say this would happen. I also worry quality will drop considerably – there won’t be the revenue to pay for the quality. So when we use words like “experiment”, “transform” and “innovate” I can’t help but think those are all ways of saying a lot of people are going to lose their jobs and a bunch of societies are going to be in real trouble because their journals that relied on papers rejected from other journals are going to see that source dry up once a journal is OA.

Glenn, looking at the land of unintended consequences is absolutely my beat. Sadly, I recall in the early oughts wondering how humanities researchers would pay their way….tin cup, grandparent bequest? Sadly, priviledge continues to prevail. My fervent goal is to keep professional associations healthy as they adapt to encourage the next generation. Every community needs a ‘place’ to gather, and in the research domains, a thriving community helps us all. What are our best ways forward?

I found that our transformative agreement with Elsevier only covers hybrid journals not fully open access journals. We still need to pay an APC for those, so of course as researchers we are going to prefer hybrid. No idea why this is the agreement. With Springer-Nature, Nature titles aren’t covered. So, we’re going to publish non-open access in Nature titles if we are so lucky…

Transformative agreements are so named because the idea was to transform a subscription journal to an OA journal. Pure OA journal are already transformed, so to speak, and so are not part of the agreement.

When we flip a hybrid journal to gold-OA we are excluding all authors from countries (e.g. Global South) where a TA is still far from being affordable, I know many journals that would simply not survive.

Exactly. Our Diamond OA journal has been open to all for 30 years, free to publish, has no budget, run by volunteers, and is indexed. This is really not so hard.

If you’ve got a steady (and wealthy) source of funding that’s not so hard indeed, but I don’t think this is the case for most of diamond-OA journals. Which journal are you talking about? Just curious.

This is an excellent and important article Alison, thank you for your accuracy of the issues and advocacy for change. Among researchers, there is fear to embrace change for what the consequences may mean for their promotion, grants, and livelihood. Change that is slow is generally for the best as it allows being able to ‘nip issues in the bud’ or at least make them as small as possible before they become riddled throughout a highly interconnected and high-stakes system, but even getting that going is hard because of how conservative academia is. Again, thank you for your on-point reflections.

Alison,

I offer up a bold idea that is singularly focused on Open Access for society publishers in the humanities and some social sciences. I call it both a business model and an attitude and give it the name “Maximum Dissemination”. The basic idea is to have the publisher make the article of record and the author’s accepted manuscript fully fungible. The knock-on effect of that is to reward innovation by the publisher but at the same time give some market power to librarians who can then choose whether all the bells and whistles are worth it; all that without compromising the world’s access to the author’s ideas.

Just Google “Maximum Dissemination” and you’ll see it described. Pay particular attention to the favorable comments and video critique given by two leading academics and a librarian. To be fair, one person who saw this presentation at the Charleston Conference in 2019 was eager to be the first person to comment from the audience. In his words, “This idea is so naive, so incredibly naive that it’s actually dangerous.”

Thank you, Alison. Great analysis.