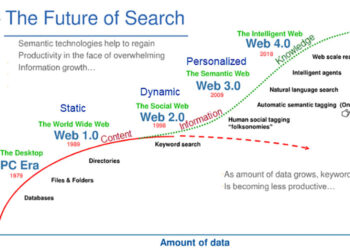

The past year has seen remarkable development in the AI-enabled services embedded in information tools across the scholarly communications industry. Looking at library-licensed content and tools, AI is powering a wide range of services for our users. Retrieval-augmented generation technologies are particularly prominent, powering experiments in search and discovery. Other applications assist readers by integrating information from multiple sources into a single synthesized text. Yet others support readers in investigating a single text, particularly longer documents, to gain understanding, perspectives, and insights. Finally, tools are emerging that leverage AI as a coach, scaffolding and supporting readers – particularly students – to foster growth in knowledge and skills as they engage with content.

From Information Object to Learning Object

I find these latter two – AI for insight and AI as coach – particularly intriguing. By transforming information objects into learning objects, these tools unlock the contents of articles and books and expand their reach beyond experts who can already relatively easily make sense of what they are reading.

In this post, I’d like to share my experiences with and thoughts about these tools by exploring three examples: Alethea, Papers AI Assistant, and the JSTOR interactive research tool.*

Alethea

Alethea from Clarivate is a teacher-driven learning environment that aims to unlock student “ability to critically read and understand scholarly content” with the goal of “turning reading-averse students into critical thinkers.” Access to Alethea is through an institutional license. Individual accounts are not available and learner access is predicated on an instructor using the tool in their course. As such, my experience here is through demonstrations and documentation.

Alethea guides students through a structured process for critical reading and deepened understanding, starting with instructor-developed questions. Alethea is integrated into a campus learning management system (LMS), which includes single sign-on, and assignment and gradebook integrations. Instructors upload reading materials into Alethea and then develop assignments around those materials aligned with course learning outcomes and goals. Instructors may also use Alethea’s AI Instructor Assistant, which supports the assignment creation workflow, leveraging instructor’s input to generate effective questions. In addition, the course instructor has access to heatmaps and dashboards that reveal the engagement and performance of the students in their course and identify where students are struggling and may need further assistance.

When a student accesses an assignment, Alethea prompts the student to read the text and highlight which parts relate to a particular question from the instructor. Alethea then presents those excerpts in context of conversational questioning with the Alethea AI Academic Coach that encourages analysis and reflection as a precursor to prompting the learner to write their own answer to the instructor’s question. Alethea AI Academic Coach acts as a kind of “Socratic interlocutor” that pushes the student to engage critically and deeply with the readings. This kind of scaffolding supports a novice in working through unfamiliar content and developing their understanding. Through this process, learners become better prepared for class discussions and incorporating resources into papers and presentations.

Publishers may be concerned about PDFs being uploaded to Alethea, as they sometimes are with respect to uploading into campus learning management systems already; however, use rights, limitations, and licensing terms that apply to courseware and other learning environments apply to Alethea as well and librarians licensing Alethea will be well-versed in such contractual parameters. Publishers that already deliver textbooks and other materials through the learning management system will likely see a strategic partnership opportunity here.

Papers AI Assistant

The Papers AI Assistant from Digital Science “is designed to enhance research efficiency by providing real-time, in-depth analysis, summarization, and contextual understanding of scholarly articles.” Papers AI Assistant relies on the end-user to generate questions for the AI to use in interrogating the document. The AI Assistant was originally released as a beta and, though you can apply to the waitlist for access, I’m told it is going to be available to the market widely in the coming weeks.

When exploring the functionality as a beta tester, I was curious how the results compared to my pre-AI tool practice of making heavy use of CTRL-F to locate keywords in lengthy texts. I found that, not only did the Papers AI save me a great deal of time by providing me with an overview annotated with links to specific sections of the text, it also often alerted me to places in the text where my topic of interest was conceptually discussed without the use of the specific keywords I would have searched. Most valuable to me is that Papers operates outside the confines of a particular content platform. Acquire or make a PDF, add it to your Papers library, and the text can be interrogated.

As with Alethea, I imagine that some publishers will immediately be concerned about PDFs being uploaded to Papers so someone can interrogate it with AI. It is useful to note though that Digital Science’s terms with AI providers do not allow re-use of any inputs for model training. Regardless, I anticipate we will see attempts to develop some sort of DRM-like technology blocks to prevent end-users from uploading PDFs into AI tools; however, I would suggest the more savvy publishers will develop a strategy to instead capitalize on this user desire path to deliver value to authors in the open access publishing ecosystem.

JSTOR Interactive Research Tool

The JSTOR interactive research tool from ITHAKA aims “to help people work more efficiently and effectively” by using AI models “to solve common problems JSTOR users face: evaluating, finding, and understanding content.” Also only available in beta at this time, those with access to JSTOR through an institution and a free JSTOR personal account can sign up for the beta.

JSTOR’s AI tool activates when the user selects an item from their search results and displays the full text. A brilliant feature is that the AI immediately and automatically asks the question: “How is “the-search-word-or-phrase” related to this text?” In my experience, this is the only AI tool that proactively demonstrates asking a specific and meaningful question to the AI rather than providing examples of the kinds of questions that could be asked.

Having demonstrated the conversational interface, the JSTOR AI then offers three buttons for queries that can be asked of every text – “What is this text about;” “Recommend topics;” and “Show me related content” – as well as an option to “Ask a question about this text.” As a beta tester, I was particularly taken with how these prompts reflect the kinds of thinking I’ve been suggesting to students throughout my career as a librarian when they encounter a text in their search results: what does it say, is it relevant, does it connect you to other information, etc.? Experts in a field make these assessments easily. Novices need scaffolding and prompts for support as they build up sufficient habits and knowledge that support fluency in evaluating and comprehending scholarly texts.

Though the beta is currently only available to individuals, this fall the beta program expands to institutions. It will be interesting to watch how the JSTOR tool develops over time. For example, might JSTOR leverage its integration with Hypothesis to develop an AI-enabled social reading and annotation experience in the learning management system that would allow groups and not just individuals to benefit from the conversational insights process?

Concluding Reflections

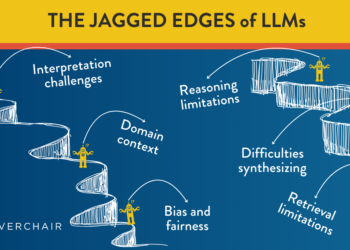

Across just these three examples are a variety of approaches to how much agency the reader has, how constrained the AI is, and which texts the AI tool interrogates. These reflect both pedagogical perspectives as well as realities and uncertainties related to content licensing, copyright, user data, and LLM services. In my conversations with the industry pioneers leading these efforts, they are both bold and cautious as they navigate the possibilities AI presents while also recognizing the very real concerns and objections raised by these technological advances.

Personally, I am excited by the possibilities these AI tools offer for moving the focus from access to information to comprehension of it. And, while students and scholars are obvious beneficiaries of these tools, other potential audiences include journalists, policymakers, business people, politicians, and the general public. I see here a glimmer of possibility for addressing what fellow Chef Roger Schonfeld termed “The Problem at the Heart of Open Access” – that, even when people have access to the scientific literature, they may struggle or be unable to make sense of it. To be clear, I’m not saying any of these tools are sufficient as they exist today to address the full set of challenges in solving this problem. Nonetheless, I’m optimistic about the possibility of at-scale environments that support understanding and comprehension and not just access.

___

* My thanks to everyone who took the time to meet with me, prepared a demonstration, facilitated access, provided a beta test account, responded to my questions, chatted with me after their conference presentation, etc., and helped me better understand how AI is developing in the industry generally and the details of these three tools specifically:

- Clarivate: Oren Beit-Arie, Senior Vice President, Strategy & Innovation, Academia and Government; Guy Ben Porat, Vice-President, Academic AI; Rachel Scheer, Director of External Communications, Academia & Government

- Digital Science: Daniel Hook, CEO; Simon Linacre, Head of Content, Brand & Press; Robert McGrath, Founder and CEO of ReadCube; Martin Schmidt, Head of Innovations

- ITHAKA: Kevin Guthrie, President; Alex Houston, Senior Marketing Manager; Beth LaPensee, Senior Product Manager; Roger Schonfeld, Vice President, Organizational Strategy and Libraries, Scholarly Communication, and Museums

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "AI-Enabled Transformation of Information Objects Into Learning Objects"

Thanks for the great summary of these tools Lisa. This is getting into the weeds a bit, but it would be nice to know what model they are using to analyze the texts. I don’t know if it’s in their documentation or not. To some extent, I guess I’m not sure how easy it might be to convince students to use one of these tools if they are just leveraging a more foundational model like ChatGPT. Students are probably going to just use the original ChatGPT interface with the pros and cons associated with that.

There’s also an element of understanding the reasoning behind a particular strategy that one might use to analyze a document. I’m thinking of your example of using Ctrl-F to find keywords in the document. You don’t just do that for the heck of it. You’ve been taught or discovered that this can lead to the parts of the paper you might be the most interested in. Will chatting with an AI tool help students understand similar strategies (It sounds like the tool from JSTOR might be good at this)? I’m not sure, but it will be interesting to see how things play out in the coming months and years.

Thanks for reading and the thoughts. It is a good question – Why would a student use these tools? A flip answer might be that they are told they can’t use ChatGPT (perhaps ChatGPT is even blocked) but can use these.

But, let’s take the question a bit more seriously. I think the answer is it varies. With Alethea, completing your course assignments and getting your grade on them is done through the tool so I think it won’t be hard to convince students to use it!

ChatGPT is perhaps closest to the kind of functionality you get with Papers AI; however, to me there is a significant difference between having a dashboard of the places in the text and being able to click to them and skim around — essentially working through an annotated PDF — vs asking ChatGPT questions about what it finds in the document/where and then getting back the page number or perhaps an excerpt of text out of context. To see the context you’d then have to open the document in another tool and scroll to that page. ChatGPT also won’t build a library of PDFs you’ve uploaded with metadata. (I’m not an expert on ChatGPT so if there’s functionality I’m missing that does do PDF annotation let me know!)

I suppose a student could take the questions that JSTOR programs and type them in to ChatGPT after uploading the PDF of an article. But, that assumes the student has already acquired the PDF to upload so on convenience it seems then why not just query it in JSTOR? I’ll also note that JSTOR has a fanbase like no other library database … even without the AI! So, for many students this would be an add-in to a tool they already really like to use.

Additionally, I’d add that none of these tools are just prompting an LLM directly with nothing more than the user’s input. They are sending the prompt to the LLM having run it through an prompt engineering process. (Similar if you will, for example, to how my library’s discovery layer does post-input processing of author name searches, for example, before submitting them to databases that only use initials and not full first names.) Long-term, it may be is less the LLM model and more the prompt engineering that creates competitive advantage in addition to other factors.

The LLM models available and in use are evolving and sometimes providers are using more than one. In all three cases, my conversations with the staff have been repeated over many months; I didn’t seek out the current information on the tech stack in writing this piece so I don’t feel like I can be confident in the data I have about which model(s) are in use. For current information, I’d reach out to the respective company for the tool that interests you.