The community of proponents of open access to content has for many years been focused on the availability of content to the public. In large part, these efforts have been centered around removing paywall barriers to access content. To be sure, paywalls haven’t been the only focus, as reusability via license assignment has been another concern. It has taken years to settle on a rainbow of colors that describe the various approaches to describing how open an item is, in what ways the openness is achieved, and the timing of the content’s release into the open world. Despite some naysayers, the progress toward a more open ecosystem has been undeniable. However, one significant gap in this march toward openness is the comparative lack of attention to the accessibility of content. Content that is inaccessible is no more open to those who need supportive reading functionality than content that is behind a paywall. Access without accessibility doesn’t serve the goal of providing federally funded resources to the public.

Over the past couple of months, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) has been drawing attention to the need to support not just Open Access as it has been traditionally defined, but also accessibility. This important equity detail was mentioned in the ‘Nelson Memo’ of 2022, in which peer reviewed scholarly content should be available “in formats that allow for machine-readability and enabling broad accessibility through assistive devices” (page 3-4).

At a first public consultation event in September, the general state of accessibility as it relates to scholarly and technical publications was discussed, including a summary of the new guidance from the US Federal government from the Office of Management and Budget as well as new rules from the Department of Justice on ADA regulations. A subsequent meeting was also held in October to describe progress by specific agencies and organizations. During the meeting, OSTP staff issued a request for voluntary commitments to support accessibility in our community. For those interested in communicating organizational commitments or ideas, the OSTP staff welcomed information via email.

Fortunately, much of the work to support accessible scholarly content already exists. The tools for accessibility are embedded in nearly every feature of the scholarly communications ecosystem. These form a solid foundation for providing accessible content, but they need to be implemented and used appropriately to be affective in providing accessible content to users. Among the advances in providing accessible content include:

- The EPUB standard was created from the ground up to be born accessible, with features embedded that — if implemented correctly — will ensure that content is readable to those with visual impairments.

- There is already robust guidance from the W3C and their WCAG 2.2 standards, which is the current benchmark for accessible web content.

- The DAISY Consortium has a freely available, open source tool, Ace by DAISY, designed to check the accessibility of EPUB files at any point in a publishing workflow. It can be used to evaluate conformance to the EPUB Accessibility Specification.

- Mathematical expressions can be created using accessible formats, using MathML, and rendering mathematical symbols is supported in every major browser.

- There are simple tools designed to easily export content from Microsoft Word directly into EPUB.

- Content has long been possible to adapt to assistive text to speech services using the NISO/DAISY Digital Talking Book Specification (NISO Z39.86).

- A broad understanding of how to create content either directly to EPUB, in XML format using the Adaptive XML publishing specification (NISO Z39.98), or via the Journal Article Tag Suite (JATS) and its related

- There is also guidance on how best to apply best practices to the use of JATS for accessibility purposeswhich was published earlier this year in JATS4R.

- Accessibility information for describing accessible products has been available in ONIX metadata since 2018.

New Regulations Coming Into Effect

Accessibility is not just a problem within the scholarly publishing world. It is pervasive on the internet. A 2024 report on the accessibility of the top 1 million web home pages found that most web pages had accessibility problems. The report details how a staggering 95.9% of websites had detectable WCAG conformance failures on their homepages, with an average of 56.8 errors per page. The most detected accessibility issue was low contract text, which was an issue on 81% of sites.

Unsurprisingly given these issues, there has been an increase in lawsuits related to accessibility problems. In the 2023 Website Accessibility Lawsuit Report, Accessibility.com tracked 2,281 lawsuits against firms for failing to meet accessibility requirements. As regulators increase the compliance requirements and legal expectations for accessibility, one should expect more lawsuits in the US and more fines in the EU for non-compliance. In part, these widespread problems have led to more robust regulation of online content provision.

In the coming months, several rules will come into effect that will drive the need for greater adoption and use of accessibility functionality when they come into effect. First in the US, Title 2 of the Americans with Disability Act will come into full force at the end of 2025. This applies to published content that is provided to the public through government agencies in the US and more broadly to the public in the EU.

In April, the Department of Justice issued a final rule for federal and state agencies that updated regulations related to Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). This rule describes the specific requirements federal and state agencies should apply for ensuring web content and mobile applications should be made accessible. A fact sheet describing the rule is available on the ADA.gov website.

Particularly relevant for the publishing community is Title II, § 35.200 Requirements for web and mobile accessibility, which reads, in part:

(1) Beginning April 24, 2026, a public entity, other than a special district government, with a total population of 50,000 or more shall ensure that the web content and mobile apps that the public entity provides or makes available, directly or through contractual, licensing, or other arrangements, comply with Level A and Level AA success criteria and conformance requirements specified in WCAG 2.1

Content providers, such as scholarly publishers should be aware of this guidance and the rule, which enters affect in April 2026. While it applies most directly to federal and state agencies, it has a cascading affect to those businesses that are suppliers to government agencies. Publishers who provide content or tools to the community that is licensed through public institutions, such as state universities, colleges, public schools or public libraries will need to be compliant with the WCAG 2.1 (or higher) benchmark.

Based on the election outcome this week, it might be reasonable to ask whether these rules will remain in effect or could change depending on the outcome. Of course, no one can foresee the future or the actions of the incoming administration. However, while the regulations might change, the ADA is more than a regulation; it is a law establishing a requirement to provide accessibility accommodations. In addition, the ADA now will also have a mirror in many respects to the EU Accessibility Act. For most publishers selling content to a worldwide audience, the regulatory space around accessibility will become much more stringent beginning in 2025, regardless of which party controls the US White House.

In Europe, the EU Accessibility Act is set to come into full force throughout the EU in June of 2025, having been adopted in 2019. This directive guides all EU countries toward consistent regulations across the EU related to accessibility. E-books, ebook platforms, discovery tools, as well as customer support pages are all defined as services under the regulation and therefore must comply with standards for provision of services, platforms, DRM, related metadata. One may not use a lack of priority, a lack of time, nor a lack of knowledge as permissible excuses for non-compliance. At a most basic level, content should include navigation via a table of contents, structured content with tagging, print-corollary notation, a clear reading order, and alt-text. In April, Laura Brady, an inclusive publishing expert wrote describing the regulation “is poised to have a seismic effect on digital publishing by influencing both emerging and developed markets.” The SSP Accessibility Subcommittee produced an excellent summary about the back in January.

Scholarly Publishers Can Improve Accessibility Conformance

Despite the progress noted above, quite a few issues remain to make the scholarly process more accessible. Some will become requirements because of the regulations noted above, while others are simply important features of the scholarly publications process that should be more accessible. Here are just three from among the suggestions that were made during the two OSTP webinars I’ll dig into more detail on:

- The process of manuscript submissions is not as accessible as it could be.

- The use of accessibility descriptive information in is lacking in information about products.

- The presence of alt-text does not necessarily mean that alt text is meaningful and helpful to those needing accessibility.

Manuscript Submission Tools

An important component of accessibility service is access to the scholarly process, which includes authorship. Several people who are print disabled have expressed to me the problems that they have had trying to use screen readers to submit articles. Their experience, as related to me, has all been disappointing. To confirm this, I reviewed the basic submission pages for three of the main manuscript submission systems. Using an accessibility assessment tool, accessibilitychecker.org, I found that none was exemplary, even on the basic portal pages. The further one digs into these systems the more challenging the process can become.

ScholarOne – Accessibility audit Score 46 on submission page

AtyponRex – Accessibility audit Score 85 on submission page

Editorial Manager – Accessibility audit Score 63 on submission page

The purpose of highlighting this is not to claim a definitive assessment of the conformance of these tools to WCAG standards. I certainly have not gone through the process of reviewing these tools in a systematic way to say one is doing better than another or that any tool is failing in a particular way. However, even at a cursory, anecdotal level, it is important to note that none reaches the 90%-conformant level that the ADA Title II guidance is demanding. This is one area that certainly deserves a more thorough analysis, not to call out bad behavior, but to draw attention to the issue in hopes that every provider will improve their conformance with best practice. Importantly as well, accessibility of submission systems isn’t covered under accessibility regulations because they aren’t public facing in the same way that products are, but it is important that they be accessible as well.

One simple way that anyone can use is simply to use the text-to-speech functionality that comes with every browser. This is a useful test to consider whether your site can be meaningfully navigated by someone with no, low, or impacted vision. Anyone can undertake this simple gauge as a place to start, regardless of your company’s size of complexity.

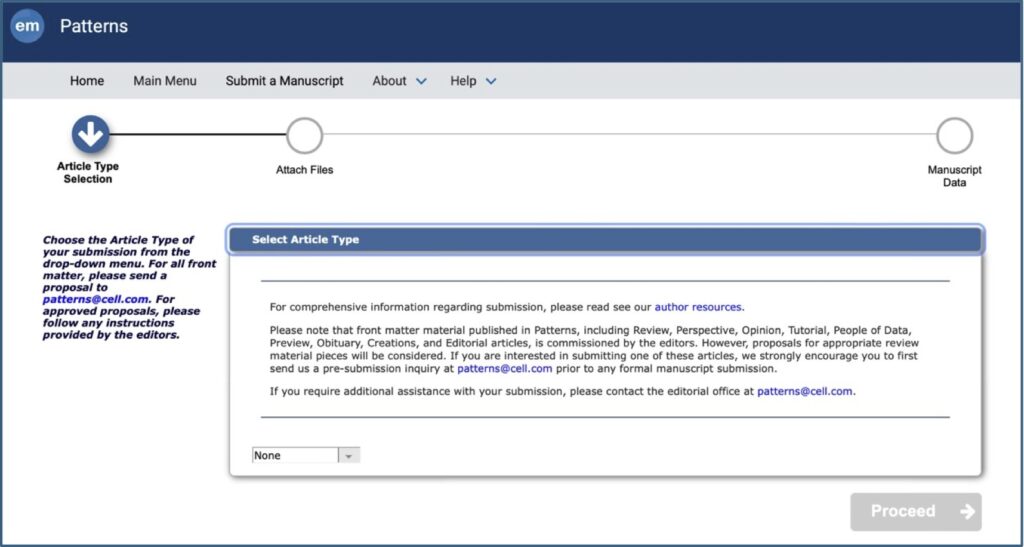

I’ll highlight the submission page for one journal that I’ve been on the advisory board for many years, Patterns, a Cell Press journal, which uses the Aries product Editorial Manager as noted above. The image below is the entry page when one attempts to submit a manuscript. As the machine-generated voice reads through the page, it seems reasonable at first, giving one a reading out of the text that appears below the header (though one might need to use the header bar to get back to the account page, that isn’t the purpose of this page, so I’ll let that slide). The problem arrives when the text-to-speech tool reaches the end of the paragraph.

To move forward in the process, one must select an option from the drop-down menu to pick the type of article to be submitted. In this image, this drop-down box list below it reads “None”. The screen reader didn’t even acknowledge that this box exists, simply ending on the word “Proceed”, which won’t work if you don’t select an article type from the list. If one doesn’t know that box exists, where it is, or what to do with it, it is impossible for them to submit their article, review, opinion or perspective for consideration. The visually impaired are left out of the process even before the process begins, unless someone is there to hold their hand throughout. This is but one of the challenges throughout the process of getting to the final “Submit” button.

Product Metadata

Another issue is the inclusion of distribution metadata about digital products. Again, much like the availability of tools to provide this information, they are underutilized. This summer, EDItEUR, which maintains the ONIX metadata model for book content distribution information, released a new Application Note for the ONIX system, Accessibility metadata in ONIX (Advanced). This Note is quite a bit more detailed than the existing application note on Accessibility metadata in ONIX, released back in 2017, which the new note expands upon and supplements. The note details how and why product accessibility information is vital, where it should be encoded, as well as how this applies to different variants of content such as audio books, PDFs, and accessible physical versions. The note also gets into technical details about relevant ONIX code lists, samples, Xpaths and crosswalk to schema.org terms.

Despite the availability of the structures to communicate this information, many publishers either don’t include it, or the data gets lost in the product distribution channels. For many print-disabled users, these data aren’t readily available when considering whether to purchase a book product. Similarly, these data often aren’t included in library records, making it difficult for users who need to know these details to understand whether content is accessible before they try to access it.

Alt Text for Images

Another significant problem in scholarly publishing is the quality of alt-text for images in scholarly publishing. Alt-text is a metadata structure for describing an image in a digital work. Far too often, content that is distributed lacks quality alt-text that describes an image.

A study published in The Lancet last December by a team led by Matthew A Crane at Johns Hopkins examined the alt-text in 1,250 academic articles from 250 different journals published between 2021 and 2023. The results of the survey are extremely problematic.

The most common alt-text practice observed across journals was replication of figure position, such as by listing “Figure 1” or “Figure 2” (150 [60.0%] of 250 journals). It was also common for alt-text to be absent (37 [14.8%] journals) or to contain no meaningful information, such as “Figure” or “Image” (24 [9.6%] journals). In some cases, alt-text replicated the figure title (14 [5.6%] journals) or figure caption (10 [4.0%] journals).

Importantly, the survey found that none of the 250 articles “Provides meaningful interpretation” of the images in the alt-text field. Only three of the 250 provided “limited interpretation”. Meaningful interpretation, as defined in the WCAG standard means that alt-text should serve the equivalent informative purpose of non-text content. For example, if an image exists, say to provide examples of stained cell images that show cancer growth abnormalities, and it exists to show what those abnormalities are, then the alt text should describe the image, what the image shows, and what important features drove the inclusion of the image in the article. Far too often the alt text field includes meaningless text, such as a file name or redundant information such as the title or location of the image. In more than 25% of the cases, the alt-text field was either empty or contained things like a file name, which is useless at best and harmful at worst.

If one were to use a tool that checks the conformance with WCAG 2.0, the tool will check the presence of alt-text. Unfortunately, these tools do not assess the quality of alt-text. If one processes an article or a web page of one of the journal articles in The Lancet study noted above, the alt-text would be present in 85% of the articles. However, that does not mean that the information in that field is useful in any way.

The process of checking the conformance with WCAG should not simply be a box-checking exercise. As described in the article, nearly every publisher has a public commitment to provide content that is conformant with WCAG standards, but the performance to these standards comes up woefully short.

The process of checking the conformance with WCAG should not simply be a box-checking exercise.

We should collectively resist the desire to feel good about conforming with the bare minimum and the letter of the law, but not embracing the spirit. Having spoken to several leaders in our community about the need to improve and adhere to accessible requirements. As noted in the Crane, et al. survey, nearly every publisher has publicly stated a commitment to conform with accessibility best practice. In general, there is a recognition of the value and its importance, and many large publishers invest in improving their accessibility efforts. In practice, most are failing to deliver on their commitments. In the coming months, the voluntary commitments will shift to becoming legal requirements for many markets.

We need to collectively question whether we are doing all we can do to support those with reading disabilities. Leadership at scholarly publishers should collectively resist a feel-good box-checking exercise and ensure that conforming with existing commitments means doing the right thing, not just appearing to do the right thing.

Publishers should be transparent in their commitments as well, as companies like Elsevier have done. There are reasons to embrace accessibility beyond it being “a nice to have service”, or even as an “unfunded regulatory mandate”. Accessible content is also good for business. According to the United Nations, more than one billion people need some form of assistive technology, but lack access. This underserved market is massive. Beyond this, born-accessible content is easier to search, discover, and be integrated in machine-processing tools like artificial intelligence. With born-accessible content, doing the right thing is also the best thing from a business perspective too.

Note: Thanks are due to Simon Holt, Senior Product Manager, Content Accessibility at Elsevier and a member of the SSP Accessibility Subcommittee, for his contributions to these issues, for his time during the Frankfurt Book Fair where these topics were discussed, and for reviewing a draft of this post.

Discussion

3 Thoughts on "Paywalls are Not the Only Barriers to Access: Accessibility is Critical to Equitable Access"

Todd, this is such an important issue to highlight. We’re committed to improving accessibility in Editorial Manager and ProduXion Manager, and have made meaningful progress in recent years, including:

– Complying with Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.2 for all new and refreshed user interfaces we develop

– Collaborating and sharing through an Elsevier accessibility guild, including learning from team members that are leading the industry on accessibility such as at ScienceDirect

– Training accessibility champions in industry best practices

– Gathering direct end-user feedback to inform data-driven decisions (i.e. ensuring actual usability, not just compliance)

– Considering auditory, cognitive, physical, speech, and visual needs

While we’ve made significant strides, especially with our User Experience and User Interface (UX/UI) redesign initiative, there’s still a lot of ground to cover given the volume of pages and workflows in our products. We’re continuously and iteratively reviewing accessibility compliance and welcome feedback on how any page or workflow could be improved. We’ll work diligently to address those areas as we advance our UI/UX initiative.

Nathan Westgarth

VP Product Management, Aries Systems

Todd, thank you for this expansive overview of accessibility in scholarly publishing. As you rightly note, accessibility needs to be viewed through an equity lens. I appreciate you highlighting the importance of the updated ADA Title II regulations that academic libraries are preparing for: https://www.arl.org/news/arl-ada-title-ii-resources-encourage-licensing-born-accessible-content/. I also wish to call out the work of the Library Accessibility Alliance (LAA), https://www.libraryaccessibility.org/. LAA is a multi-consortial organization that advocates for improving library e-resource accessibility. We welcome publishers and vendors to engage with us in our independent accessibility evaluations and adopting model licensing language on accessibility.

*Full disclosure: I currently serve on the LAA Steering Committee.

Hi Todd,

Thank you for this comprehensive and fair reflection. I’d like to share some brief insights into the Public Knowledge Project (PKP) and our ongoing efforts to enhance web accessibility across our software platforms—OJS, OPS, and OMP.

Accessibility Audit: We recently conducted our first comprehensive accessibility audit, which included users relying on assistive technologies such as screen readers and braille keyboards. This audit resulted in significant improvements to the Default Theme[1] and the development of an Accessibility Statement[2] as well as an Open Accessibility Conformance Report (ACR)[3].

Inclusive Usability Testing: PKP has been conducting usability testing sessions for some time, and we’ve incorporated users with disabilities into past sessions to ensure our platforms meet diverse needs.

Permanent Accessibility Project: Accessibility is a core priority at PKP. We’ve established a permanent accessibility project to address issues promptly and effectively. This includes a dedicated accessibility issue template in our GitHub repository[4] to streamline reporting and resolution.

PKP develops the world’s most widely used open-source journal publishing platform, with over 50,000+ active journals[5] relying on our software. Our community-driven approach emphasizes inclusion, ensuring that accessibility is not just a compliance checkbox but a genuine effort to make knowledge more open and accessible to everyone.

As you rightly point out, accessibility is fundamentally about people. It’s about ensuring that everyone—including individuals with disabilities—can access and contribute to knowledge. We’re committed to going beyond minimum compliance by involving real users with disabilities in shaping our solutions.

Your post is an excellent milestone in this ongoing journey. After all, how can we truly claim something is open if it isn’t accessible?

Best regards,

Israel Cefrin

Digital Accessibility Specialist – Public Knowledge Project (PKP)

[1] https://docs.pkp.sfu.ca/pkp-theming-guide/en/theme-default

[2] https://docs.pkp.sfu.ca/accessibility-statement/en/

[3] https://docs.pkp.sfu.ca/acr-vpat/en/

[4] https://github.com/pkp/pkp-lib/issues?q=is%3Aissue%20state%3Aopen%20label%3AAccessibility

[5] https://rpubs.com/saurabh90/ojs-stats-2023