Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Mark Huskisson. Mark is the Co-Chair of the Assembly of the Commons for the European Research Infrastructure, OPERAS, and strategic adviser to PKP | Public Knowledge Project. He is an independent consultant, speaker, and contractor at The Husk Agency.

This is the third and final article in a guest series reflecting on the main themes and ideas gathered and discussed at The Munin Conference at the end of 2024. Part One and Part Two are also available.

In Part Two of this series, as part of assessing open science, we looked at the UNESCO International Decade, which addresses the critical issue of unequal access to science, technology, and innovation. A core aspect of ‘the Decade’ will be facing the longstanding challenge of bridging science and society.

We generally recognize that the work of scientists underpins health and prosperity, where research and innovation drive economic benefit. Nature’s open letter to the incoming US President looking to harness science for prosperity and safety identifies the importance of global collaborations, trust, and evidence-based decision-making. However, governments globally need to give scientific advice greater salience in policymaking, as it is not routinely used. Science and research have and will continue to improve our lives and global cooperation is the only viable approach to global problems

Transparency and curiosity sit at the heart of science and open science advocates claim it can provide better outcomes. But is it possible to identify demonstrable socioeconomic benefits from applying open science? Is it possible to identify causality between the application of open science policy and its promised benefits?

Identifying Impact

The shift to open access in publishing has always been heralded as holding the potential to remove barriers to knowledge and information. However, despite all the attention it has received here and everywhere else, open science’s impact on innovation, the inventive process, and societal impact is not well known.

PathOS aims to help establish causality between open science policies and real-world, material outcomes. The project has, so far, identified beneficial links between open science and academia and society, but it has yet to report on economic impact such as productivity and innovation. Without equivalent agreed measures to the widely accepted impact metrics of research evaluation, it is hard to recognize if the promise of open science and all its constituent parts are being realized.

For now and the foreseeable future and at least until we identify causal links we will continue to pursue the widely accepted impact metrics of research evaluation, with all their limitations and implications. This creates behaviors that support and continue to reinforce the existing scholarly communications industry and its stakeholders. For, as Eli Goldratt writes, “Tell me how you measure me and I will tell you how I will behave.”

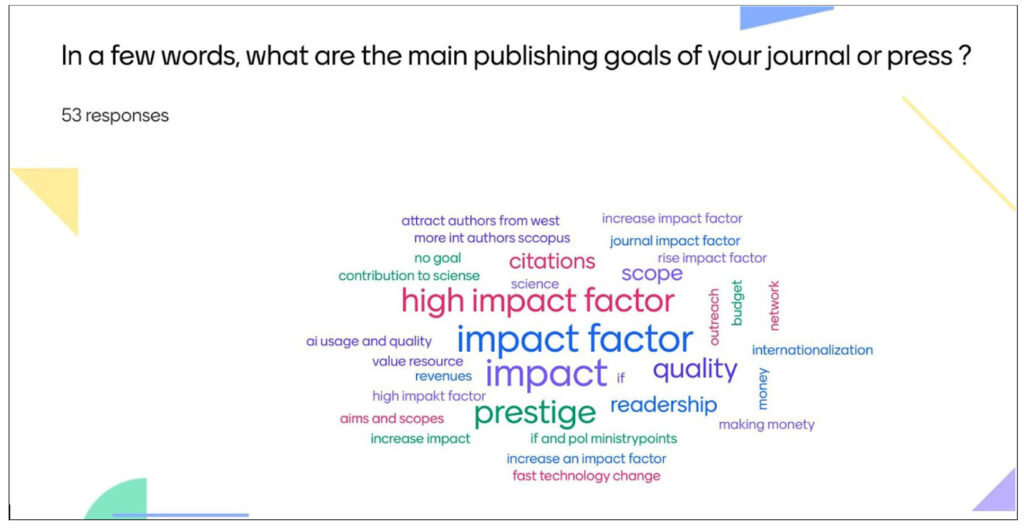

The resulting behaviors cause many stakeholders to stray into the arena of (the disputed) Goodhart’s Law – when a measure is used as a target, it becomes a poor measure. The scholarly publishing ecosystem incentivizes journals and publishers to pursue citation counts at the cost of other considerations. As a consequence it could be argued that many within this system flirt with quantitative fallacy, where decisions are made based solely on quantitative observations (or metrics) at the cost of all other considerations, such as societal or economic impact.

A quick insight into the current hold of citation metrics on journals or publishers could be seen at a recent Paradigm Services event in December, where the audience was asked, “What are the main publishing goals for your journal or press?” The most common answers were, predictably and unsurprisingly, impact factor and citations. The reasons may be manifold but the goals, objectives, and resulting behaviors are remarkably consistent.

This powerful and pervasive research evaluation culture continues to compound the inequalities of the international knowledge system that enjoys “strong institutional support and significant historical roots” that Philip Altbach identified 40 years ago. The dominance of the research evaluation culture serves the separate but umbilically linked industrial complexes of academia, publishing, and academic libraries with a widely agreed, consistent, and simple set of metrics on which tens of thousands of decisions are made.

Considering it was four decades ago, Altbach was remarkably prescient when he wrote, “It is unlikely that even the best intentions, buttressed by resolutions of the United Nations or the programs of UNESCO, can dislodge the basic power relationships among nations, especially when those in the industrialized nations, who hold power, have shown little inclination to yield it in the past.” This could well be a contemporary opinion and brings us back to the extensive current activity of UNESCO and the best intentions of many across the industry and the scholarly communications ecosystem.

Identifying Societal Impact Through Policy Making

Information is critical in the global digital knowledge economy where it has attained the materiality of capital and commodities. And, as innovation is the cornerstone of societal progress, advancing technology, economies, and scientific understanding, mapping the global influence of published research on industry and innovation should help give us an insight into the impact of information and knowledge on society and economies.

Research and innovation have been identified as key areas to reignite sustainable growth and drive productivity and small firms (SMEs) are key to innovation in many economies but 68% reported difficulties in accessing scientific research, limiting their ability to exploit relevant scientific knowledge. A study seeking to assess the impact of the Department of Energy’s (DOE) open access mandates on research and technological development in the U.S. found that the mandated OA articles were utilized 42% more in patents. With resource-constrained SMEs particularly benefitting from the open access mandate, citing research about 50% more than enclosed articles.

At around the same time as the Munin Conference in November, Abdelghani Maddi (Sorbonne Université) gave a talk on “Open Science as a Catalyst for Invention: Evidence from Patent Data” at the Nordic Workshop on Bibliometrics and Research Policy (NWB2024). Maddi identified that open access (OA) publications are 38% more prevalent in patent citations “It presents a novel insight into the utilization patterns of OA literature by inventors, reflecting a paradigm shift towards leveraging openly accessible scientific knowledge in the inventive process.”

Maddi found that the majority of sources within Non-Patent Literature (NPL) are Scientific Non-Patent References (or SNPRs) that identify the information and inspiration that drives invention and innovation. Identifying these NPRs gives us an insight into how information, refined into knowledge, attains materiality in the modern knowledge economy through the inventive process of creating patents and technology.

Therefore, one way to assess impact is to measure innovation through patent activity we can identify a great deal of correlation between science output and inventive processes. Potentially allowing us to get one step closer to identifying evidence of causality between scientific activity and socioeconomic impact. Of particular interest could be the measures of university-industry R&D collaboration and intangible asset intensity as published by WIPO in the annual Global Innovation Index.

For those of you who avoided business school (well done, I am envious of you), intangible asset intensity is the critical measure of the shift toward knowledge-based industries where intangible assets, rather than physical capital, are the key value drivers. Intangible assets result from intellectual property and hold a huge amount of potential to create value for companies, economies, societies, and individuals. It is an excellent indicator of how well science and research are providing a scaffolding structure for technological innovation.

In the modern digital economy competitiveness is derived from intangible rather than physical assets. WIPO writes, “Intangible assets, while not immediately apparent to the average person, profoundly impact daily life by fostering better economic prospects, generating higher-paying jobs, improving product quality and innovation, and delivering more reliable products.” Therefore, intangible asset values are an excellent measure for grasping the drivers of economic growth and for formulating policies.

The research identifies the value of OA content in driving innovation, particularly in biology, medicine, chemistry, and computer science, and “…the symbiotic relationship between open science and inventive activity [and] highlights the transformative potential of open access resources in driving technological innovation.” This suggests that policymakers would do well to identify the growing importance of open science to innovation.

As one such policymaker, the European Commission’s Think Open strategy sees open source infrastructure as core to this policy including the development of an open source platform. As part of the EC’s policy shift to open science, it announced that the Open Research Europe publishing platform will move to an open source, open access, open peer review (PRC, “publish, review, curate”) initiative in 2026.

Whilst access to OA resources helps inventive activity, they do not build the local capacity to undertake and share that research which is critical to that country or region. Reiterating the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science that science needs to move beyond just sharing to make sure that “not only that scientific knowledge is accessible but also that the production of that knowledge itself is inclusive, equitable and sustainable,” it is about equitable production and engagement in the creation of knowledge and the ultimate desire to democratize science.

Indonesia – Observing Societal Impact from Open Science

As a case study, Indonesia offers data and conditions that can help illuminate whether open science can drive impact. Importantly, it is a country that has operated with a far lower level of influence from the heavy burden of the research evaluation incentives evident in the scholarly publishing industrial complex. As the fourth most populous country in the world, Indonesia has seen extraordinary growth in scholarly publishing over the past decade, first appearing on the industry’s radar due to topping open-access publishing charts in an article in Nature in 2019.

The continued growth in output since this 2019 article has been no less extraordinary. PKP’s data on Harvard Dataverse identifies nearly two million articles published in more than 20,000 journals in these five years. This rapid dissemination of scientific research, and the collaboration in and the sharing of knowledge, has been achieved through government policy and leveraging of open-source publishing software such as Open Journals Systems (OJS).

Government legislation is critical in generating a massive growth in publishing. These decrees have driven the massive growth of multilingual, local, and contextual science publishing:

- 2014 – universities were obligated to make all scientific publications openly available;

- 2017 – undergraduates, masters graduates, and doctoral graduates had to publish their work in a scholarly publication;

- 2017 – Bahasa Indonesia made the mandatory language in all scientific contexts.

These decrees were followed by Indonesia’s Law Number 11 in 2019, a comprehensive 25-year plan with direct policy to improve the quality of research and education and to foster innovation to address contextual societal challenges and to increase Indonesia’s competitiveness on the world stage. This was a centralized attempt to drive impact through the combination of policy making and open science.

With very little evidence of influence from industrial activity such as APCs, BPCs, or commercial enclosure in this enormous growth in journals and articles, it is probably the best example of a non-industrialized publishing ecosystem, at scale. It has thrived on extremely low overheads, aided by central policy, and primarily utilized Diamond Open Access.

By examining WIPO’s Global Innovation Index to see whether these policies have delivered real world impact. If not evidence of direct causality there seems to be a real correlation in outcomes as Indonesia has advanced most of all nations over this past decade, moving from 85th overall to 54th, developing “similarly to China and India,” and “performing above expectations on innovation relative to their level of economic development.”

Within this overall improvement, the two key indicators Indonesia excels in are University-Industry R&D collaboration, where it has risen rapidly from 38th to 5th in the world over the decade in question and in the critical Intangible Asset Intensity. Indonesia is now 13th in the world (up from 19th in 2023), with a rapid increase in the creation of patents and proprietary technology.

Observing Intangible Asset Intensity in this way measures an economy’s shift toward knowledge-based industries and innovation-driven businesses like technology and pharmaceuticals that depend on the development of intellectual property and innovation. Innovation itself is not the goal, it is a tool to impact change. Or, if you are a business or organisation, a tool to increase value to our stakeholders (or shareholders).

The extensive open data from Indonesian scholarly publishing allows us to study what open science might look like without the widespread behaviors inherent in the publishing industry, where quality information that is contextual to Indonesia’s circumstances is accessible and not held behind paywalls and made freely available to all citizens, institutions, and corporations in their language. This openness and relative lack of commercial enclosure has been enabled by open source software and infrastructure and appears to have driven research that has benefited Indonesia’s economy and society as seen in the Global Innovation Index.

As Altbach wrote back in 1981, “…knowledge has no national boundaries” we need to acknowledge that Indonesia’s economy has benefitted enormously from increased access to research undertaken in the Global North. The shift to OA, mandated or otherwise, or shared through agency agreements by EIFL or Research4Life has led to hugely beneficial knowledge spillovers to nations such as Indonesia. These spillovers are particularly important to innovative yet resource-constrained SMEs in countries worldwide.

It is far too early to say this is clear evidence of causality between open science and benefit for society or economies (I can already hear you sharpening your pencils to list 101 reasons why). It may prove to be no more than a correlation at the macro level. The World Economic Forum identify multiple structural issues for why research and innovation policy does or doesn’t work. But the data looks encouraging and deserves more study.

Using this macroeconomic approach, we can begin to see a shift in national economic competitiveness and national fortunes due to policies targeted at driving science for the betterment of society. The very reason we do science.

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Guest Post: Reflections from The Munin Conference Part Three – Measuring Impact"

It appears that the worrisome parts of this model the diamond access are not discussed. And the diamond access model there is no payment required to publish or to access which means someone else has to pay. It seems to be assumed that the government whichever government that is will foot the bill. That would also mean that the government gets to choose what research gets done and what research gets published. This could cause group think and repression of new in different avenues which and other venues might be called innovation. Was there any attention given to the balance between censorship either by the government or by the groups in charge versus who pays?

I cannot imagine that anyone went to that conference on their own nickel without Support of an organization to pay their wages, transport, hotel, and registration those are real expenses.

Do these models all assume 100% payment by government if they do I think that’s a danger to the scholarly endeavors and to innovation

The Indonesian case study is fascinating Mark, thanks for sharing this. As you note, it’s impossible to know how much of Indonesia’s rise up the WIPO Index is attributable to its adoption of open science, but it’s certainly plausible that it has made a meaningful contribution. In the world of policy evaluation that’s about the best anyone can hope for (see https://www.betterevaluation.org/methods-approaches/approaches/contribution-analysis). It will be fascinating to see whether India’s One Nation One Subscription deal yields comparable gains in a few years’ time, since India and Indonesia are taking very different approaches to opening up scientific knowledge: https://www.psa.gov.in/oneNationOneSubscription.