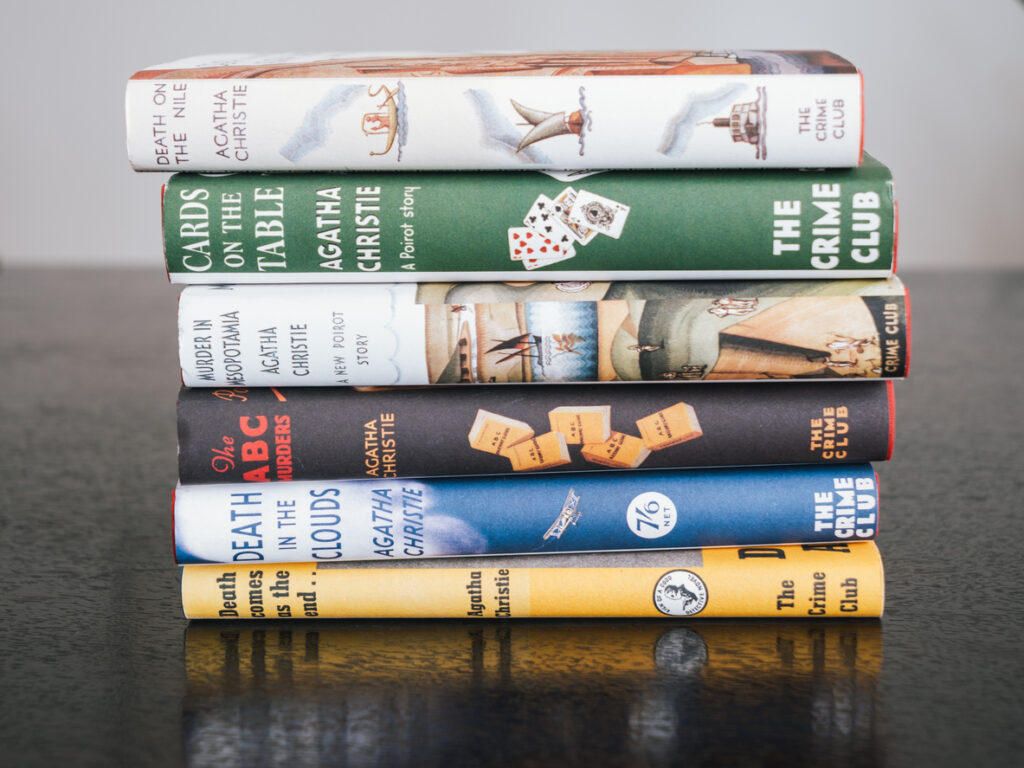

Quick! Without resorting to Wikipedia, Google or ChatGPT, which Agatha Christie novel was published in the United States in 1939 under the title, The Patriotic Murders? I’m guessing the answer isn’t popping up immediately in your head. While such tidbits of knowledge may be helpful in a competitive bout of pub trivia, most of the time, such details get buried. Back in the day, in satisfying the questioner, one might have been able to turn to the now unavailable resource, The Detective Novels of Agatha Christie: A Reader’s Guide by James Zemboy (MacFarland, 2007). It’s a niche publication that fifteen years ago would have found shelf space in a library’s reference room.

Advocates of artificial intelligence legitimately note that ordinary people don’t want to have to flip through some alphabetically arranged roster to find an answer. It’s disruptive to one’s creative thought and process to be so distracted. So, yes, there’s Wikipedia, Google, and ChatGPT. In today’s world of those technologies, does anyone see any newly-emerging genre of reference works? Is there a diminishing need for the genre? Does it all just get poured into a database?

On my reading ottoman is a paperback copy of The Bloomsbury Handbook to Agatha Christie. As proof of frequent use, it has multiple Post-It flags and sticky notes hanging off its pages. That collection includes 20 substantive essays by scholars actively engaged in research on Christie and the means by which she both entertained, as well as revealed the English society of her day. Taken as a whole, the volume provides the reader with a sense of how the novelist is viewed through a variety of scholarly lenses and suggests areas where additional analytical study might be beneficial.

Reference works like the Bloomsbury Handbook have a commercial value. They can be used across a spectrum of readership. They create awareness of new avenues, new disciplinary approaches. (Ecocriticism? Psychogeography? These are concepts in today’s scholarship not used in the 1970s or 80s.) From the business perspective of a publisher, such a collection of material is sensible, serving several potential markets. The library can purchase the printed hardbound or gain platform access to licensed digital material while the isolated general reader can wait for availability of a paperback sold through Amazon.

Agatha Christie scholarship has a proven interdisciplinary appeal. For example, The University of Texas Press makes available The Poisonous Pen of Agatha Christie, an in-depth look at the means by which Christie employed her knowledge of chemistry and pharmacology. Which poisons were used where? What was the means of delivery? Were there occasional missteps? Breaking out those answers in the tables and appendices making up the bulk of the book’s pages again provides long-standing value. (The book was originally published in 1993; off-hand I can’t determine whether my paperback is the result of print-on-demand or part of a 2011 print run when the book moved to paperback.)

A recent update on Christie’s use of poison would be the book by Dr. Kathryn Harkup, A is for Arsenic (Bloomsbury, 2016). Equally useful in terms of its substance, the book’s approach seems intended more for a general readership and less for an academic one. (The lines of anticipated readership blur, but most would-be criminals only seek a single chapter when planning a next move.) As a contrast, Springer released Agatha Christie and the Guilty Pleasure of Poison in 2022 as a part of its Crime Files book series. I’d love to have that one as part of my personal reference collection, but pricing of the print as well as the licensed content model of access precludes me from doing so. Seeking out the details can be expensive.

St. Augustine Press provides The Importance of Being Poirot by British historian Jeremy Black. The marketing blurb calls it “a thrilling masterpiece, seducing historians to read fiction and crime junkies to read more history.” The slim volume covers the events and cultural shifts felt in England over the course of Agatha Christie’s life as a published author. Black begins immediately post-World-War-I, setting out some of the defining political aspects of the 1920s. His coverage ends with events in the mid-70s and Christie’s death. While disclaiming any great depth of knowledge, he demonstrates familiarity with other Golden Age authors of detective fiction. On the downside, at less than 200 pages, there’s not as much as one might expect in terms of supplementary materials. (A bibliography would have been nice.)

The Ageless Agatha Christie, edited by J.C. Bernthal, published by MacFarland in 2016, includes two contributed essays pertaining to library and information science. A third essay in that volume touches on Christie’s work in translation, another point of investigation for an author whose novels have been translated into more than 100 different languages, producing more than 7,000 different editions. A similar collection, edited jointly by Rebecca Mills and J.C Bernthal, is Agatha Christie in Wartime (Routledge, 2020).

In my snapshot of reference works on Christie, I haven’t touched on the scholarly monograph. On my Kindle, I have the digital work by Dan W. Clanton, God and the Little Grey Cells. This particular book hits on a facet of Hercule Poirot largely overlooked in thinking about Christie. Biblical allusions are deeply woven into her writing. Society in inter-war Britain expected that readers in the first half of the twentieth century would recognize phrases and images drawn from the Bible, although fewer readers nowadays are likely to pick up on those. What was Christie saying when including such references in her mysteries? (As an example of what might be expected, in an analysis of The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Clanton draws attention to Poirot’s referencing the Book of Esther and his commitment to hanging the miscreant “as high as Haman” in pursuit of justice. In a different Christie novel, Poirot is positioned as the prophet Nathan, speaking on behalf of the poor man’s “little ewe lamb”.) Dr. Clanton’s writing style is lively and well-suited to a non-theologian or non-academic reader. (His publisher is T&T Clarke, a Bloomsbury imprint, specializing in theology and biblical studies.)

As an aside, for those not inclined towards a full-length monograph, Oxford University Press has scheduled a volume on Agatha Christie for release as part of their “Very Short Introduction” series. It is due out in October, 2025. This shorter genre of scholarship (running roughly 20,000-30,000 words per book) appeals to a rising readership of those short on time but with a need to orient themselves at a solid, if baseline, level on a topic.

I know enough of the scholarly marketplace to make an educated guess as to what the thinking on pricing for Clanton’s God and the Little Grey Cells might have been. There would be a relatively limited print run for the hardcover, primarily intended for the institutional library market; in that context, the hardcover was priced at $115.00. The Kindle edition was roughly a third less in cost. When it came to my notice – about five months after the book’s initial publication – the hardcover was already out of stock. If I really wanted to read this (and I did), it had to be in the Kindle format. My academic reading group was honestly scandalized that I would pay that much, given the limitations of licensed ebook access. In truth, I winced as well but sometimes, one’s intellectual curiosity can drive an impulse buy.

As it happens, I was thrilled to discover that T&T Clarke will be releasing a paperback edition of Clanton’s book in December of 2025. I’ve preordered it, paying the $40 dollars asked by the publisher. (Why does no one offer a discount when a reader pays for both print and electronic?) I’ll have the beneficial affordances of two formats, but I’d have preferred an increased print run of the original hardcover.

Self-published as a reference work is Agatha Annotated. It’s not entirely duplicative of the content found in Zemboy’s The Detective Novels of Agatha Christie: A Reader’s Guide, but when I first encountered Kate Gingold’s work, I wondered if she was even aware of Zemboy’s effort. Gingold is adopting a decade-by-decade approach to identifying obscure terms, foreign language phrases, and historical events as encountered by the reader of Christie’s work. The initial volume covers books published during the 1920s, titles such as The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Self-published titles such as this emerge when traditional publishers step away from supporting a particular type of knowledge gap. Perhaps artificial intelligence will preclude any future need of information artfully arranged in alphabetical order, noting variant titles and clarifying unfamiliar or obscure allusions.

Unsurprisingly, this little tour through monographs, scholarly articles and assembled reference works is indicative of a studious environment in transition. There’s a genre of scholarship suited here to numerous disciplines and (theoretically at least) works are available at every practical price point. Agatha Christie remains a market force! At the same time – as Jane Marple and Hercule Poirot begin to fall into the public domain, when we have access to collections like Project Gutenberg, the technology of ‘bots and untested AI – how will these genres of scholarship change? In another five years, will a Gen Z visitor look at my relatively limited reference collection and think, “Oh, isn’t that quaint”? Snark will undoubtedly spill over, but upon what other genres will serious readers rely?

In light of current pressures on higher education, connecting the humanities with pub trivia may seem tone-deaf. But scholarship, to prove itself worthwhile, must ultimately permeate through into daily culture. It is a quiet process that requires time. Economic feasibility is important; equally important is support for the moment when human curiosity seeks out a quick answer but instead begins to explore a fascinating and complex body of knowledge. Good pub trivia is built on reliable, detailed research.

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Repackaging Christie — Does AI Have a Role?"

That’s a very eloquent contribution which I thoroughly enjoyed. Your book clubs must be great fun.

Is the answer ‘Murder on the Orient Express’?

One, Two, Buckle my Shoe I think