Type the word “bioRxiv” into into Google’s search box, and the first autocomplete suggestion is biorxiv impact factor. Number three is biorxiv journal. To be clear, bioRxiv is not a journal, but a preprint server. It is not indexed by the Web of Science and, more importantly, has never received an Impact Factor. At the same time, Google’s algorithm has discerned that enough users have searched for bioRxiv’s Impact Factor to suggest the result.

Since it’s launch in November 2013, bioRxiv has been wildly successful, attracting submissions, readers, social media attention, and citations.

Each bioRxiv record summary includes the paper’s altmetric score and usage figures. It does not include how many times the preprint has been cited. Nevertheless, with a little work, you can find this out too.

Consider the preprint, “HTSeq – A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data” by Simon Anders and others. It was first deposited in bioRxiv on 20 Feb 2014, with a revised version being posted on 19 August 2014. The paper was subsequently published on 15 January 2015 in the journal Bioinformatics.

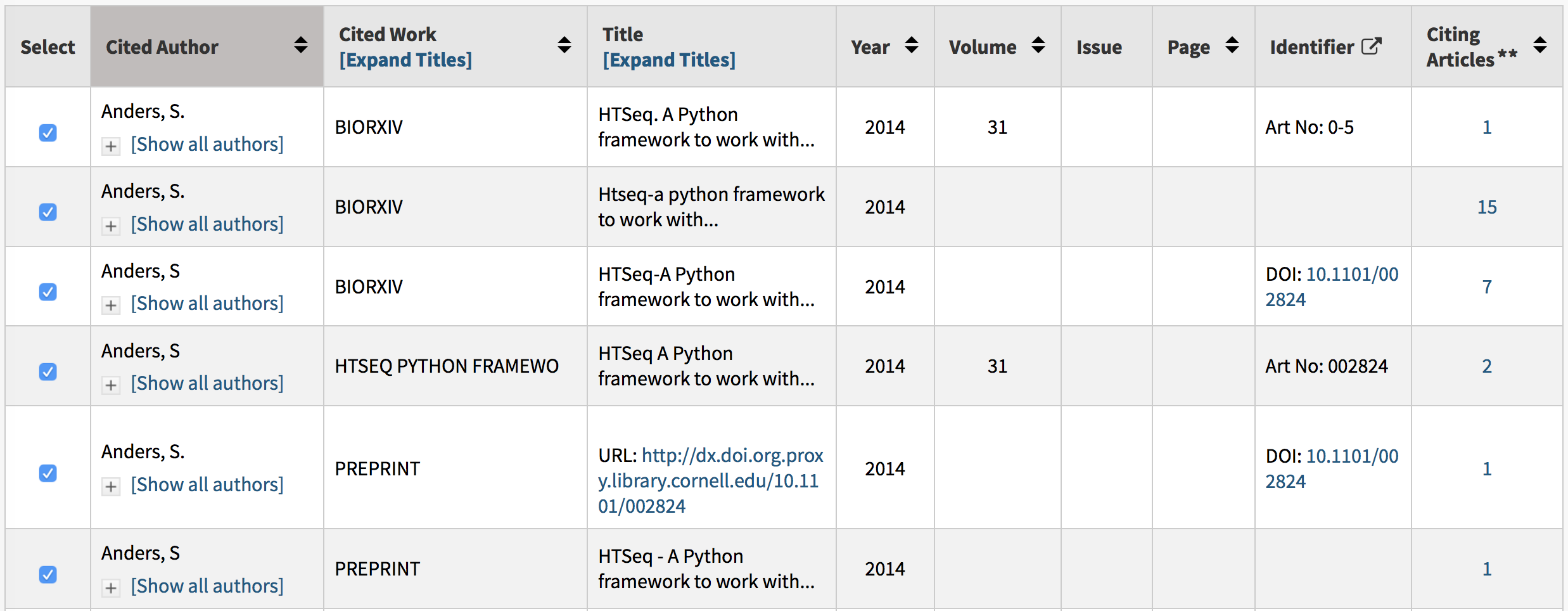

If you do a cited reference search in the Web of Science for Anders S* as the author, biorxiv as the work, and limit the publication date to 2014, you’ll get the following results:

For the first three references, biorxiv is listed as the source of the paper; references five and six list “preprint” as the source; and number four omits a source completely. In total, we find 27 references to the preprint, which, in a practical sense, is a pretty small number of citations compared to the 2304 counted toward the journal article. Even so, of these 27 citations to the bioRxiv version, 3 were made in 2015 (the year the article was published in Bioinformatics), 3 were made in 2016, 8 were made in 2017, and 2 have come out so far in the first few months of 2018.

Why do authors continue to cite a preprint years after it has been published in a journal?

It’s hard to understand why an author would still cite the preprint years after it has been formally published in a journal. Readers may have downloaded an early version from bioRxiv and continue to cite it as a preprint; they may be copying or reusing old references; GoogleScholar may be preferentially sending readers to the bioRxiv instead of the journal. While bioRxiv does its best to search for published papers and update its website with accurate metadata, this information is obviously not reaching all readers.

Similar to the problem of authors continuing to improperly cite papers that have been corrected or retracted, citing earlier versions of a paper may promote incorrect or invalid scientific work. Still, even if the bioRxiv version was identical in every respect to the published version (in the above example, the final version in the bioRxiv was submitted the day after the final version was submitted to the publisher), a citation to the bioRxiv is a citation that cannot be counted towards a journal’s Impact Factor and associated metrics.

This redirection of citations is not just a bioRxiv problem. You’ll find references to journal articles as if they were published by the arXiv, PubMed Central, Academia.edu, and ResearchGate (see example above). Understandingly, some publishers are not happy that these repositories are stealing eyeballs and citations.

A citation is much more than a directional link to the source of a document. It is the basis for a system of rewarding those who make significant contributions to public science.

The scope of this problem is not well understood. While there is great enthusiasm for incorporating preprints into the lifecycle of publication, there is a dearth of research on this topic. There are currently well over 8,000 citations to bioRxiv in the Web of Science.

At present, there is no mechanism for a user to export metadata from bioRxiv to match with citation records from the Web of Science, Scopus or Dimensions. Unfortunately, my request for a dataset from bioRxiv to study this problem was rejected as Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory looks to develop a long term solution to providing metadata to interested parties.

A citation is much more than a directional link to the source of a document. It is the basis for a system of rewarding those who make significant contributions to public science. Redirecting citations to preprint servers not only harms journals, which lose public recognition for publishing important work, but to the authors themselves, who may find it difficult to aggregate public acknowledgements to their work.

Discussion

60 Thoughts on "Journals Lose Citations to Preprint Servers"

Hi Phil

One of the questions is whether or not the article which appears as a preprint subsequently is published in a journal that is behind a pay wall.

The related question is how important is the work so that it becomes established by citations of others and the IF as a “good housekeeping seal of approval” becomes less important within the collegial community than to those who default to or seek the IF for various measures rather than the value of the content by peer citation outside of limited peer review of a journal.

It seems to me that this is less an argument about preprint journals and more aimed at the reaffirmation to the publishers of the value of the IF (which has been questioned) and thus the pay-walled academic journal.

Roger’s excellent article in Ithaka on the avenue for growth within the journal industry lies more on providing value-added services, a platform economy more like Amazon than a “product platform”- perhaps more like Elsevier and its parent rather than the traditional journal/book publishers.

Perhaps the wrong platform was emphasized in the Nature IPO?

This is an interesting topic, and something that my group has been exploring recently.

“GoogleScholar may be preferentially sending readers to the bioRxiv instead of the journal”

This can be easily checked. A search in Google Scholar using the title of the document will let you know that (as of today), Google Scholar directs users to the final version in the journal, and not only that: since the article is OA from the journal, the primary OA version that GS displays is also the journal version. I’m sure Google Scholar provided access to the biorxiv version from the moment it became available. Therefore, it is no wonder to me that many are still citing the bioarxiv version. Most of the interested readers downloaded the bioarxiv version during the year that it took for the article to be formally published. By the times it was published, most of the interested readers already had a copy, and probably not many bothered to replace it with the final version.

Of course, it would be interesting if a simple to use mechanism could be implemented in preprints, to check whether the version you have is the latest version (something like CrossMark, but for preprints). Even if that were accomplished, I don’t think many researchers would bother to update their copies.

“Redirecting citations to preprint servers not only harms journals, which lose public recognition for publishing important work, but to the authors themselves, who may find it difficult to aggregate public acknowledgements to their work.”

Yes, journals are losing citations, primarily because they are not adapting to the preprint paradigm. However, I don’t think authors should be very concerned about this. Google Scholar understood and for the most part solved the issue of “aggregate public acknowledgements” almost 14 years ago, by grouping together all the different versions of the same document that are available on the Web. If you check the GS record for the article that you mention in your piece, you’ll notice that GS has grouped together the publisher version, the biorxiv version, and several other versions in PubMed Central, SemanticScholar… and that it provides all citing articles, regardless of which version these citing articles cited https://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=3577483169728972966&hl=en&as_sdt=0,5

I wonder if publishers can help to solve their own problem by insisting that references in paper they publish include the final publishing location (in cases where the article has been assigned an issue already, or at least published ahead of print on the journal site), and not preprint server versions?

Although I expect this has some theoretical complications when it comes to making sure the final reference is to the exact same content that was actually used in the research.

Your comments following Albert’s are important:

“I wonder if publishers can help to solve their own problem”

Recall that scholars exchanged information, collegially. The idea of the “journal” was an opportunity to collect and more widely distribute within the communities of interest. As Albert notes, with Google Scholar as one example, today, AI engines can search the web and compile all versions and make them accessible whether preprints or IF certified journals/articles. The key is that the community wants the information as do others in communities not coextensive with researchers whether stamped as final or not.

As I note in my comment, above, Roger points out that, for publishers, the conventional scholarly journal may not produce the growth that they require, or, as discussed, here, be able even to maintain, particularly if the IF, good housekeeping seal equivalent, looses its cachet as a default standard as a short cut for relevance.

Web of Science and equivalent aggregators for research are matched with similar databases of trade publications where entrepreneurial journalists scavenge for critical opportunities. And there are similar such for the blog and listserv communities that have a much greater reach into both the for and not for profit area for relevant information and who use Google Scholar as one such engine with increasing intelligence.

There may be more promotional savvy in today’s researchers where such access has greater benefit than the narrow academic journal, regardless of IF.

At bioRxiv, as well as linking to the published version, we also pass on matches between a preprint and the published article to crossref so that the two DOIs are connected. It should therefore be relatively easy for a publisher to use crossref tools to identify bioRxiv DOIs in a reference list that should be replaced with journal DOIs.

I think the efforts that biorxiv makes here are appreciated, but do you know if other preprint servers (COS, PeerJ, arXiv, SSRN, etc.) do the same?

At COS, all of our preprint services contributors can supply or update their preprint with a “final” DOI if they choose that references the published version of the research. The final paper’s DOI then overrides the preprint DOI in the citations section.

To be clear, the inclusion of the published version of the article is up to the authors and it is not systematically added to the platform as it is at biorxiv?

To David’s question…the decision to add a publication DOI to a COS preprint is totally up to the author. Both DOIs then become part of the preprint, but if a publication DOI is added it does become the DOI used in any subsequent citations.

In response to David, Preprints.org – like bioRxiv – updates metdata in Crossref to add a journal doi to a preprint where we find it through an automated search. We also allow authors to submit details about the journal publication manually for cases where we haven’t made the match.

Richard– are you saying that an author could cite the preprint and the publisher could replace that citation with the published paper? Should this not be the author’s decision? What happens if the versions are not the same?

Hi Angela – apologies for the confusion; I ought to have said “could” not “should”. I’m just pointing out that that a publisher could identify citations for which there is an updated version. One option would be at proof stage to flag for the author and ask if they wish to update these to the published version or if it’s one of those rare instances (as Jessica points out) that there is a particular rationale for citing the preprint.

Hi Richard,

As I briefly suggested at the end of my comment there, I think my concern about automated replacement like that would be how to ensure that the content of the articles is actually the same. I’m sure it’s very rare that the final published version is significantly different from the preprint version, but to preserve academic integrity I think it would be necessary to have the authors confirm that either version would provide the correct information required, before submitting their final draft.

Of course this would require authors to read the official version, which would sort of defeat the point of the preprint version.

I’m sure it’s very rare that the final published version is significantly different from the preprint version

I’m not sure this is the case across the board, as most manuscripts see at least some changes via the peer review process. This is particularly important in the Humanities, where there is an enormous amount of editing and revision that happens post-acceptance. In these fields, specific quotes and their location in the article are often footnoted, and those actual quotes may no longer exist in the published version. More on this here:

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2015/03/25/guest-post-karin-wulf-on-open-access-and-historical-scholarship/

Apologies David, you’re right.

I’m coming at this from a Pharmaceutical background so was thinking more of specific data/methods which would generally not change massively once accepted for publication, although again, not always.

In all academic areas though I think the decision over which reference goes into the paper should be a judgement made by the authors.

David’s comments about the humanities’ typical editing process are accurate, but we typically don’t even have to deal with this preprint citation problem at all because it’s not normal in the humanities to dump preliminary versions of articles into a repository like arXive.

However, during my time as a science publishing production editor, it did seem like lots of articles did get significant updates, including new data, in proofs. So we definitely shouldn’t minimize the possibility that the preprint and version of record differ in scientifically important ways.

As Alberto has pointed out, Google Scholar has been pooling citations between preprints and journal records for years. It’s not clear to me why other services don’t do the same – especially now that preprint metadata in Crossref can link to the final version.

To your list of reasons an author might preferentially cite a preprint, I’d add this one: restrictive journal length limits could force researchers to remove information, rendering the final version less useful than the preprint.

…and in the COS case, preprints can be easily associated with and linked to the original data sources, analyses, code, and other public project information that make the experience far richer and potentially more informative.

We have been interested in the issue of citation switching since launching bioRxiv and the “now published in” link under the abstract of a preprint is intended to remind readers that a journal-certified version of the paper exists. Getting at the reality of this behavior, though, will require thorough, large scale, long term studies. This is one of the reasons why (as I explained when “rejecting” your request for the dataset) there will be a repository of bioRxiv content and metadata set up specifically for text and data mining, for use by all scholars: we don’t have the resources to handle every request we get for this kind of access and don’t want to say yes to some and not others. But on the sample of one paper you highlight, leaving out the year the paper was published (news spreads slowly sometimes and Google Scholar may index a journal less frequently than a rapidly changing site like bioRxiv), it looks like there were 13 citations to the preprint made after the paper was published and 2304 to the published paper. Is this “loss” a cause for concern? Maybe the link on bioRxiv helped minimize it. And maybe some of those 13 authors deliberately intended to refer to information that was in the preprint but, for a variety of possible reasons, wasn’t in the published version. A citation is primarily an acknowledgement of the source for an assertion made in a paper. I’m personally not convinced it’s always, or simply, a reward for “those who make significant contributions to public science”.

John, thanks for your response. Without a dataset, the best I could do was anecdotal evidence. I suspect that journal articles capture the vast majority of cited references, but that loss–whether it is 10% or 1%–is still a concern as it represents a reward system that is not working optimally. While many eschew the very idea of using citations as the basis of a rewards system, we can’t ignore that such a system is the basis (like it or not) for evaluating journals and those who publish in them.

Interesting post Phil, thanks for writing, it would be good to know what CrossRef is doing/thinking as an organization and community here, I believe CrossRef can help track citations to both preprint and final published article. I know there’s been some initial research and investigation into a similar examples with Altmetric data for the preprint and final published article, but I don’t believe there are any firm conclusions reached yet. The question I guess for publishers and bibliometrics experts is would combining the two sources of citation in some way (preprint citations and citations to the final published article citation make sense). Am sure there are a number of challenges such as trying to calculate IF, but surely some of the industries smartest minds are considering this ? Perhaps we’ll have an update, or more discussion in person at the SSP Annual Meeting, hope to see you there.

“bioRxiv is not a journal”

The thing is looks like a journal, behaves like a journal (submission guides and all) and so appears to be a journal.

No surprise people treat as if it were a journal.

Seems like much ado over <2% bad citations to a recent, highly cited article. Isn't this just simple sloppiness in citation practices on the part of authors, reviewers, and editors? Nothing new there (Ole Bjørn Rekdal's Academic urban legends (OA) is a good read on sloppy citation practices).

Considering the long, overlapping pipelines between writing and final publication, neglecting to sync up preprint citations to the final is an unsurprising oversight. Seeing a citation to the journal “ResearchGate” instead of the OA publisher is more surprising, but maybe it shouldn’t be. The citation was from a Scientific Reports article, and with 30,000+ articles a year, how much quality control can go into individual articles?

I can’t afford to access the published version. Why should I cite a version I have never seen & can’t afford to see, unless the author will send me a copy (in which case I use the final reference)?

In terms of the infrastructure, I expect that the recently introduced DOI for Preprints linked to the DOI for the published article will facilitate more citations of the version of record.

As a journal editor, I’ll never be surprised that citations are not perfect. It’s an intense process every issues of copyediting and proofreading those proportionately same number of pages of text compared to the rest of the pages

Which is also why I thus have to wonder why the emphasis here is on the authors. I can think of a fair number of reasons why the authors may have cited the preprint – many of them already mentioned in the comments here. But, why would the editors/publishers of the journals in which they published have allowed this without correction?

Not an unreasonable question, but one that means more time and money spent by journals in a market where prices are already seen as too high. Earlier today I spent some time with our Production group discussing setting up automated systems to catch any citations to preprints so those could be clearly labeled as such (https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2018/03/14/preprints-citations-non-peer-reviewed-material-included-article-references/). That’s going to mean building something, monitoring it and maintaining/updating it over time.

And then asking an editor to check every single preprint reference to see if there’s a published version means even more financial commitment. Further, what if the preprint version contains assertions that are not present in the published version (and relevant to the citation)? Should an editor have to read both versions and make that call?

And then there are journals that don’t do copyediting in order to save costs, and that don’t really do corrections at the proof stage.

I totally understand the costs of proofreading and copyediting as one who oversees my journal’s budget (with the support of an amazing managing editor as well as that from the publisher). Nonetheless, one can’t help but think about how many times we are told that these too high prices are a result of ensuring quality. I’d welcome more transparency about publishing costs across the industry but if prices are too high at publishers that are cutting corners on copyediting etc and those same publishers are showing profits, they profits are coming at the expense of quality and we have a lot bigger problem that authors citing preprints.

It’s a rock and a hard place. If you add editorial steps, you not only increase costs but also slow down the schedule. Meanwhile, various OA venues provide no or few editorial controls and even hold them in contempt (e.g., PLOS ONE’s view of not assessing quality or originality). As for the profitability issue, to repeat a point I have made before, profitability varies greatly from publisher to publisher. Fewer people want to pay for the services they demand.

We see this cognitive dissonance frequently. As a user, I want extra service X, or why haven’t you built in technology Y — while at the same time demanding lower prices across the board. If you want new stuff and more work done on your behalf, then it has to be paid for somehow.

This is perhaps another advantage for the big commercial publishers who can 1) add these new services/technology at scale, resulting in a lower cost per title and 2) can absorb some extra costs due to having large enough margins to create some wiggle room. When those same expectations are put on not-for-profits or those with smaller margins, it creates a dilemma.

I would also argue that “profits are coming at the expense of quality” is not limited to the larger, commercial publishers, but is a widespread issue across the landscape. We are in an era of “good enough” being sufficient for many purposes, and many journals are pushing the boundaries to find the minimum quality standards that are acceptable to those paying (readers or authors).

David:

The fight to the bottom and the expectation of receiving the top only reminds me of you get what you pay for. Or as the man observed: He had very deep pockets but short arms.

It seems to me that it is a pretty fine line to walk here – to argue that somehow the published versions have immense value-add over the preprints (e.g., copyediting, etc.) while at the same time acknowledging that publishers are cutting back on the very things that are used to make that claim. Perhaps we librarians should asking questions about whether open copy is functionally equivalent and stop paying for value-add that isn’t, in reality, being added? That copyediting is being discussed as an “extra” in this thread is really quite surprising to me.

I would argue that the main value of published versions over preprints is the peer review process, and in the case of fields where it is the practice, the post-acceptance editing and revision.

But you do make a good point. There are publishers that sell themselves on quality and price accordingly. There are other publishers looking to compete on price, and they often make cuts of things they think are disposable. The problem comes from publishers claiming quality (and pricing for it) while at the same time making those cuts. To even further complicate things, those most likely to notice the problems that arise from cutting corners are the users of the product, and not those who are paying for it.

What about a service like PlumX Metrics which aggregates various metrics, including citations, downloads, social media activity and more? It seems like a more holistic view like what PlumX provides could help ensure those who contribute significantly to public science are still recognized and rewarded even if the final published versions of their work are not what is cited 100% of the time.

Tom Abeles’ assertion that the journal industry provides “value-added services” is generally correct, especially for authors whose first language is not English. However, Jessica Polka and John Inglis (above) both add to the list of editorial actions that render “the final version less useful than the preprint.”

To this list should be added the demand that occasional short passages modified from one’s earlier works, which are picked up by anti-plagiarism software, should be further modified to bring them below the radar. Having struggled to craft a mot juste, sentence juste, or even a paragraph juste, in order to expressed an important idea with clarity and elegance, it can be immensely frustrating to have to rework a text to limit the damage.

A few concepts/thoughts go through my head while reading this article and its comments:

1) authors typically use the first citation that they placed in their reference archive (EndNote or otherwise) and may not bother to look for and/or update the entry with a more recent published reference.

2) authors often copy the citations that others use, without bothering to look to see if the paper has a more appropriate reference… and place the copied reference in their reference archive.

3) authors are creatures of habit and will continue to cite in the same manner, relying upon what is already in their reference archive.

4) authors chose to use the citation that they think is the most readily available to the readership (irrespective of whether the published paper is in an OA journal).

5) authors referencing behavior is reflective of where they go to find literature.

6) general sloppiness of referencing is an indication of how little attention/importance authors place on the accurate reporting of their references… unless it is their own papers.

While I have no empirical data to support any of the above comments, they certainly reflect (in a general sense) everything I saw during my days in academia.

I itemize these comments, because they seem to point towards one screaming solution regarding the next generation of smart reference archive software solutions. Wouldn’t it be great if while you are online, the reference archive software reaches out behind the scenes to find the most recent correct references, based upon the information you have provided to it. The software could make itemized suggestions to the author of a more correct reference, as well as provide additional details like retraction notices, a DOI, offer correct wording/spelling, other similar papers, include metadata, etc. >> then we start getting into smart referencing, and the author becomes empowered to reference papers accurately and responsibly. Improvements of this nature would offer a huge benefit to researchers around the world with limited access, or who have English as a second language.

Perhaps this is already in the works. Perhaps it is already available! If it is, please forgive me for my ignorance, and don’t flame me. I’m just trying to bring to the community what I think might be a good direction to proceed… it is hard to fix a population of researchers. It is best to make the reference archive tools they use smarter, so that the researcher becomes empowered and that referencing becomes better.

At our single-title, nonprofit publisher, our contract editors or I fact-check every single reference in every single paper. We find a high number of citations to articles published at ResearchGate and third-party sites rather than the publisher’s site (and thus the version of record). We also find lots of errors in author names and other parts of citations, and find that often this has carried through an author’s previous published use of a reference…indicating that other journals do not do this level of fact-checking and correcting. What IS their job if not this? Invoicing for APCs, I suppose.

The Author has the blinkers firmly on and missed one obvious reason (nicely pointed out in the first comment) and there is so many comments from within the Ivory tower here to boot just to top it off. I can’t afford to access the published version. Why should I cite a version I have never seen? There is even suggestions to reference the final published version and in effect ‘pretend’ I have seen that version.

There is a counter-argument that preprints increase citations, since they are already known by the community. See e.g. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/asi.23044 where it was found that arXiv preprints are cited, but the highest rates of citation were among papers in Web of Science that had previously appeared in arXiv.

If you do a cited reference search in the Web of Science for Anders S* as the author, “biorxiv” or “bioinformatics” or “htseq” as the work, and do not limit the publication to any date it is possible to extract at least 38 different formats of citations either to the Bioinformatics article or to the biorxiv preprint. The most cited variant naturally is the Bioinformatics article with more than 2300 citations, but the second most cited is a faulty variant with 127 citations, where Web of Science mistakenly assigned the DOI of the biorxiv preprint (10.1101/002824) to the cited article, thus these citations are not connected to the Web of Science record of the article. I checked some of the citing articles, and they had the correct DOI (10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638). So it seems that the matching algorithms of Web of Science might have some trouble with such cases.

The percentage of lost citations is larger than a few percent: I could identify 313 extra citations: 128 to the biorxiv preprint, 185 to the Bioinformatics article, compared to the 2331 correctly assigned citations to the Bioinformatics article. Although this is a quite common problem with highly cited articles in Web of Science regardless of preprints. If you look at the second most cited article from Bioinformatics from the same year (10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351) it has 552 correctly assigned citations, and at least 32 “lost” citations.

It seems that journals might lost some citations to preprint servers, but more likely they lose more citations because of data handling issues. And the probability of this of course is higher for highly cited articles.

To make things a bit more complicated, just take a look at the actual Python package the publication describes: hhttps://htseq.readthedocs.io/en/release_0.10.0/overview.html#paper

The authors give the following reference to their own work: “Simon Anders, Paul Theodor Pyl, Wolfgang Huber, HTSeq — A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data

Bioinformatics (2014), in print, online at doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638”

It has the correct DOI of the article, although the publication year is not 2015 as for the final “printed” version of the article, but 2014 as for the biorxiv deposition. This does not make things easier for those who try to cite this work correctly, and for those who then try to match these references…

When you look for the same article and “references” (i.e. not connected citations) in Scopus – you find that majority of omitted citations belong to Bioinformatics and not to BioXriv (some also belong to a source: “HTSeq – A Python Framework to Work with High-throughput Sequencing Data” ) But omitted citations point to Bioinformatics 2014 instead of 2015. Is it the influence of preprint in BioRxiv or to “Published (online) 25 September 2014” https://academic.oup.com/bioinformatics/article/31/2/166/2366196 i.e. “article in press”, “online first”, “in print” and alike?

Yes, I agree, preprint servers steal citations, but a lot less than other mistakes – made by authors in referencing and by poor matching algorithms in databases.

For someone who systematically uses arXiv, this discussion is surreal. In my field the arXiv version is the version of record: publication in a journal is mostly for administrative reasons. Preprints on arXiv can get updated after publication, and it is the journal version that can be outdated. Journals do tend to insist that we cite journal versions, as is of course in their best interest, but citing a version that we did not read distorts the chain of information.

Therefore, citing journal versions is not just needless work, it is also bad practice.

More on the use of arXiv: http://researchpracticesandtools.blogspot.fr/2018/03/the-open-secrets-of-life-with-arxiv.html

I’m curious if this is field dependent, or if overall behavior has changed since some of the earlier studies covered here (https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1306/1306.3261.pdf) which suggest that citation (and readership) rapidly shifts away from the arxiv version once a journal version exists.

Preprints on arXiv can get updated after publication, and it is the journal version that can be outdated.

This would seem to me an argument against citing the preprint. If the point you’re trying to support is removed from that preprint, it is no longer a relevant citation. Is there a “citation rot” term that is the equivalent of “link rot” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Link_rot)?

Thanks for the link to the 2013 study, note however that the authors caution that their results “underestimate the impact of arXiv e-prints that have a published alter-ego”. Unfortunately I do not know more recent data, but certainly the behaviour of people is strongly field dependent.

Yes, the possibility that arXiv preprints get updated is in principle problematic when citing them. You could cite a specific version, but hardly anybody does that. Rather, we trust authors that the changes are improvements and that no important information is lost. Certainly citation rot occurs, but mostly for the trivial reason that page and formula numbers can change. (Sorry, no data on this point either, only speaking from experience.)

The fact that many authors update their papers on arXiv even after publication in a journal means that they value quality over stability. In my humble opinion, having versions of record is not essential, giving credit via citations is also not essential. The primary purpose of an article is to convey clear, useful and accurate information, and this sometimes requires many rounds of feedback and improvement. Of course such activity is of zero value to publishers, who would rather have you publish another paper than correct the first one.

I was thinking in terms of Humanities publications, where the research output is the argument, and one often uses direct quotes which are cited. If the article continues to change, these quotes will cease to exist, rendering your own argument less valid.

I think there’s also something important about preserving the historical record of research. If I claim something that is later proven wrong, is it okay for me to go back to my paper and change it so it looks like I was right all along? Could I change my paper to lay claim to someone else’s ideas that they released after I originally wrote my paper? There’s value in versioning, but great care must be taken, each previous version must be preserved, and authors need to be careful to cite the specific version to which they refer. This creates more work and potential confusion for authors and readers (not to mention historians). Sometimes it’s better (and often more career rewarding) to write the next paper, rather than going back and making changes to an existing paper.

David, considering that humanities scholars basically don’t use preprint repositories at all—and therefore sidestep the entire problem presented in the post and discussion—I’m not sure why you keep bringing up the humanities. I more-or-less agree with you about stable versions of record, but I don’t see how the example of the humanities is going to help you convince a physicist anything about the norms in the field of physics.

As publishing practices evolve, they are often imposed upon different communities despite the specific and varied needs of those communities. Those setting policies prefer simpler, “one-size-fits-all” mandates, ignoring the subtle differences that would make for a more effective set of rules. The Humanities research community does not see the same funding levels as the biomedical world, yet the same Gold open access requirements are being foisted upon both. Usage and citation half-lives are very different in different fields, yet we seem stuck with very few choices for embargo lengths.

Many in the research community suffer from this type of myopia — this is the way I do research, this is how my community works, thus it is universal. It becomes easy to just dismiss a major portion of the research community when you are unaware of the way they work, so I think there’s value in considering different perspectives.

David, I agree with your response, but I guess I see you doing the thing you say shouldn’t be done: Using standards from one field to limit another field. You criticize the norms surrounding preprints in physics by saying that those norms don’t make sense for the humanities (and I agree that they don’t), but why would considerations from the humanities matter to a physicist if their norms *do* work for them? If you want to argue with a physicist that the norms in physics are problematic, I think the best rhetorical strategy is to justify your reasons in relation to the field of physics.

I’m sorry if I gave that impression. I was responding to someone who clearly stated:

Therefore, citing journal versions is not just needless work, it is also bad practice.

This is not a philosophy that is universal, nor one that works for every field, so I suggested an example of the Humanities where it would be problematic. I did not try to impose the needs of Humanities scholars upon physicists, just pointed out that a sweeping statement that citing journals is “bad practice” is not applicable everywhere (and tried to explain why).

I think I did additionally make an effort to argue why there may also be some issues with the statement in the field of physics, supplying data that shows that much of the field does not follow this practice (or at least didn’t at the time of the research, a few years ago). I also made an argument for why having a historical “version of record” is important, which certainly holds for physics as well as any other field, and made some suggestions about why versioning can lead to confusion for many parties.

You may not think my argument particularly convincing, but when someone is making universal statements about how research should work, it’s fair game to talk about other areas of research where things aren’t quite the same. And I think my initial argument about “citation rot” is as relevant to physics as it is to any other field, particularly as the response generated was that physicists don’t cite specific versions of a paper, and just generally hope that no information is lost. If you can make a better argument (since it seems we are generally in agreement), I’d love to read it.

David, I think we interpreted the original comment very differently; it seemed to me that he was speaking specifically to the norms in his field only. He began “In my field . . . ,” and I read the rest of the comment to be limited to that scope (therefore: “In my field, . . . citing journal versions is not just needless work, it is also bad practice”), so I didn’t read that comment as “universal” at all, and your bringing in the norms in a different field seemed to me as a total non sequitur. Now that you’ve explained your rhetorical intention in bringing up the humanities, I understand where you’re coming from relative to your reading of the original comment.

All of your physics/science-discipline-specific logic makes basic sense to me and I am not now nor have I ever in this thread criticized it, so there’s no need to repeat any of it for my benefit (but I am in the humanities now, so I’m not the person you need to be convincing).

My comments could have been clearer too, I did not mean to make a universal statement, and I welcome David’s point on direct quotes in humanities. Still, I think that the importance of having a version of record is in danger of being overstated, because having such a version is a practice that arose from ancient technical constraints, and moreover aligns with publishers’ convenience and profits.

Actually, the article as a format may be obsolete, and there are ideas that it should be replaced by some hybrid between successful platforms such as Wikipedia, StackExchange and GitHub, see Gowers’s blog:

https://gowers.wordpress.com/2011/10/31/how-might-we-get-to-a-new-model-of-mathematical-publishing/

The difficulty is not to imagine something better than the current system, the difficulty is to make the transition. To do this, we may first think about which features of the article are important, and which ones can easily change. A good start would be to accept that articles evolve: most objections can probably be addressed by keeping all versions available, and having good version control that shows who did which modifications. Another evolution might be not to cite whole articles as we do now, but to cite specific statements, parts, equations, data, etc.

All really good points! And apologies for continuing to bring the Humanities into the conversation, but our resident historian, Karin Wulf, wrote a really interesting post about this a few years back: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2015/04/16/version-control-or-what-does-it-mean-to-publish/

Yes, very nice post with many good comments. A pity that the post we are not commenting ignored that discussion and took such a narrow perspective.

If one looks only at STEM research prior to the first journal, we had letters between a small community. Thus, exchanges readily were understood to be evolving the knowledge, not only advancing but often debating results. Publication widened the audience but also fixed a publication in time. It also changed the audience and purpose.

When that became cumbersome, parallel journals such as Phys Rev Let allowed for early notice but soon took on the permanence of a traditional journal largely, I would suggest, because of the pub/perish pressures. This was/is the problem when “print” on acid free paper announced the fixity in time. But for researchers the latest version is the current foundation until one finds that a flaw in the foundation causes a crumbling of the structure and a rebuild.

Wikipedia and variances thereof provide point to where the next layer should go either to advance or to rebuild when the flaw appears. We saw this when rocket o-rings failed on a launch vehicle or black boxes from a crash point out problems.

As suggested, the fixed nature of print in a digital world points towards the idea of a more fluid information dissemination means than the “journal”. All the various publishing “tools” for tracking listed in various discussions in SK such as crossref, Science Direct (topics, too) point towards the need for both current and historic tracking when the current goes “off the rails”.

The problem is compounded by the wider audience often less interested in and understanding of the on-going exchange itself but rather the fact that it is published (with highest Impact Factor) which becomes, de facto, an argument for the journals’ existence in its current embodiment and one which publishers use with various embellishments to validate the journals’ importance.

If one understands the history, pre “Transactions” in the mid 17th century, for scholarly exchange, and one sees the various efforts, such as pirates, various ArXiv’s, wiki’s, blogs, etc to bring back the collegial exchange in a transformed embodiment, then arguments for journals are a form of resistance or a flaw in the foundation of scholarly exchange.

Similar issues appear in the humanities with the paradigmatic example of who was the author of Shakespeare’s plays. In the social sciences one sees this in the rise of heterodox economics and the biological/medical sciences have examples, with the rise of modern research tools, showing just how shaky certain foundations are. Angels on the head of a pin?

I agree with Sylvain: surreal comments. For me the question is the opposite: why would anyone link anything other than an open repository, which is generally open access, open source and hosted by a reliable organisation?

The publisher’s version is usually linked anyway, for those whose peculiar tastes or needs require it. The opposite is not true, hence linking the publisher’s version adds needless work for the user.

As Google Scholar has shown, it is possible to determine that citations to journal articles and preprints refer to the same underlying work. The problem is that the developers of Web of Science and any other service with this problem either 1) want to separate citation counts for preprints and published journal articles, for philosophical or more nefarious reasons or 2) invest so little in their platforms that they do not care or do not have developers capable of solving this issue. The responsibility to canonicalize citations lies with the companies that sell data, not with authors or preprint servers.

There are a number of similar comments on this subject on SK. Since this is largely a forum for the publishing industry, one wonders whether there is a measure of the sentiment within the research community, outside of the publishers, regarding access to the articles rather than the journals. In other words are the “Arxiv’s” and the journals several possible ways for researchers to move the exchange of knowledge closer to the early scholarly exchanges and the intent when Philosophical Transactions were first published?

Has pre publishing and post reviews merging to this collegiality stripped of the “Impact Factor” and Journal “polishing” that has become a de facto evaluation convenience- one that, as reported here, has research libraries, and perhaps others, calling that value into question whether priced singly or in “bundles”.

Perhaps the profit margins are a signal that the mark-up on the “value” provided makes the argument of such value ring hollow?