“Disruption” sounds sexy, like “Inception” sounds sexy. It also sounds harmless enough — there was a slight disruption at the back of the classroom. But “disruption” has specific business and technology implications, and tracking these to common usage can provide some insights we could miss otherwise.

In a US News & World Report article from June (“Is the Academic Publishing Industry on the Verge of Disruption?”), the term is used to compare the “disruption” open access (OA) journals might have to academic publishers to how e-books are disrupting the book publishing industry.

But the disruption of e-books isn’t the same as what open access proponents are hoping their efforts will yield.

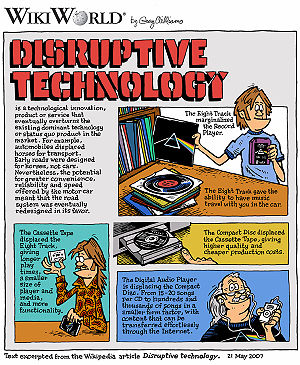

There are two phases of disruption as postulated by Clayton Christensen — disruptive technology and disruptive innovation. I wrote about these in a post in April. Disruptive technology is often just a harbinger of a disruptive innovation. But I want to refresh things a bit further.

A “disruptive technology” is one that usually preserves the output the market desires (good cars, good light, good journals, good books), but reshuffles the underlying value chain in such a way that some old players are sidelined and some new ones emerge. In our world, online is a disruptive technology for printers, not for publishers. Some printers have left the field, and platform providers have entered. Because technology is very frequently sustaining, even as it drives change, one could argue persuasively that online has been a sustaining technology for academic publishers — preserving its core functions while actually making it more efficient and effective.

A “disruptive innovation” is a market-oriented change, one that revolutionizes by changing the purchasing preferences of the market. The mass-produced Model T changed the purchasing preferences of millions, despite being based on old technology. The disruptive innovation wasn’t the car — it was the assembly line. For music, the disruptive innovation wasn’t the MP3 or digital, but the iPod. In both cases, and many more, the market changed forever because the innovation made the market better. The e-book existed for years before the true disruptive innovation arrived — the Amazon Kindle, with its built-in Whispernet connection at no cost, low-cost books, and so forth. The market responded quickly.

OA is cited in the US News & World Report and elsewhere as the disruption we’re facing. But I don’t see how it fits. It’s not a disruptive technology, because it uses the same technology we all use to reach the majority of our readers and users. So, is OA a disruptive innovation in the academic market?

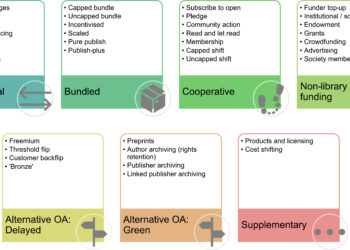

It’s hard to say, because OA is not one thing, even inside the Gold/Green color schemes.

There is what I’ll call “parity Gold OA,” which uses the Internet to recreate the editorial and brand quality of top-tier journals. These journals are using the Internet technology, but it’s not disruptive because the vast majority of journals have successfully grappled with the Internet. Because the same processes and positions and costs seem to be part of achieving editorial and brand parity, the playing field is pretty level, and subject to normal value-equation shifts, not disruption.

Then there is what I’ll call “mega Gold OA” for journals that eschew some aspects of editorial review in order to keep a relatively high volume of low-priced publishing going. The recent introduction of PeerJ as an even lower-priced (seemingly) option indicates where this part of the OA market may be headed — into price wars and fewer services for authors (or requirements for author service). Minimalist Gold OA seems closer to a disruptive innovation. These journals don’t view readers and their proxies (institutions, aggregators) as the market, but rather view authors and funders as the market, and they sell services rather than an end product. New value proposition? Check. New market? Check.

In the US News & World Report piece, Heather Joseph of SPARC is quoted as saying that in the last year-and-a-half, “we really saw an incredible explosion of new outlets, new models in particular, coming into the marketplace.” It’s clear that these are coming into the marketplace to change it from a readers market to an authors market. But are these new approaches sufficient to change the overall market?

It all comes down to how great a challenge is shifting academic publishing to a market that sells services to authors and their proxies rather than finished information products to readers and their proxies.

First, we have to accept that mega-OA is part of the same market as traditional readers-pay journals. This may not be the case — thousands of papers have been published in mega-OA journals without any apparent effect on the submission rates to traditional journals or to parity OA journals. So, there’s a potential distinction here in how authors use these mega-OA journals in the market. If mega-OA journals are viewed as inexpensive ways to publish incremental work easily and at a low price, these journals will have a hard time moving up-market, and their potential for disruption decreases. The appearance of PeerJ as a clear lower-cost alternative suggests the market is headed into a price war.

Are there many authors demanding to pay to publish? Only 2% of traditional journal revenues come from author fees, and gold OA only accounts for 5-8% of all articles published. Authors aren’t accustomed to paying for publication in most fields. This means the price mega-OA journals are battling against is “free” if authors are the purported market. This is a difficult price to beat, and diminishes the disruptive potential even more. Recent data from PSP suggests that OA is losing a little ground as an option for authors, with fewer articles published as OA in hybrid OA journals in 2010 than in the prior year, despite more available outlets.

There is also the problem of where the money to move the market toward mega-OA disruption will come from. There seems to be no easy answer to this profound barrier to any significant switch in the market. Austerity programs, mixed funding priorities, price pressures, author preferences, market precedents, and many other factors suggest little funding slack and less enthusiasm for new spending to support a sustained interval of major market transition.

There is not even really a moral high ground differentiating the current approach within the academic community, which is where an appeal like this would need to resonate. On a recent episode of “Marketplace” from American Public Media, Robert Darnton from Harvard’s libraries says:

We the scholars do the research, write the articles, referee the articles, serve on the editorial boards — all of this for free — then we have to buy back the product of our own labor at a ruinous price.

As we’ve noted in other posts, there is no guarantee that if a market shift were to occur we’d never hear:

We the scholars do the research, write the articles, referee the articles, serve on the editorial boards — all of this for free — then we have to pay to have these things published by a third-party OA publisher, at a ruinous price.

A shift of market players doesn’t mean an end to market pressures and incentives.

Disruptive innovation is a high bar that requires not only a major technology to arrive and be transformed into something profoundly enabling to a latent market need — it also needs a market that is ready, willing, and able to follow that technology into a market shift. The benefits have to be clear and compelling, not debatable and abstract.

Right now, if market forces were the only forces at work, I’d say that disruption isn’t likely. Most authors can publish at no charge. Most scientists can get the information they need. Free review and editorial volunteer duties are common to all approaches presently on the table because of how basic academic market incentives work. (And can you imagine the scandals we’d see if authors and reviewers were paid real money? We have enough problems with non-financial incentives and indirect benefits to publication.) There is no clear market force driving a broad adoption of mega-OA approaches.

Despite that, various participants in the market are trying to shift the market for academic publishing from a market for academic publishing products to a market for academic publishing services; so that the market shifts from one of users and readers to one of authors and funders; and so that the market comes to believe that one path is virtuous while the other is not. We are no longer talking about disruptive innovation. We’re talking about something new — disruptive legislation and disruptive administration.

In that case, it’s possible we’re seeing a new type of disruption being invented right before our eyes. I have an inkling that this explains why legislative bodies and funding bodies have been full of OA talk while most working scientists still don’t pay much attention. And while I’m still learning to live with the terms, I can say that adding them to my vocabulary has helped me see things more clearly when I read lay press accounts of “disruption.”

Consider them your totems when you enter the dreams of others . . .

Discussion

18 Thoughts on "Disruption — Are We Seeing a New Type Emerging in Academic Publishing?"

Indeed Kent, there is a big difference between market driven disruption and government driven disruption, but neither is new. For example, in the electric power supply industry new hydro was regulated out in the 1960’s, new nuclear in the 1980’s, and new coal fired power is being killed today. Subscription scholarly publishing is just not used to being in the crosshairs, which are always looking for new targets. I have been tracking this phenomenon for four decades. The hardest part, when a crusade hits you, is to be labeled the bad guy. Market disruption is reality based, but government disruption is not. It is perception based.

There is another disruptive change occurring, which is the extension of copyright and collapse of fair use. Libraries have not traditionally been high security facilities, and many remain accessible to the public. Further, photocopies were often extensively distributed. This made informational accessible to a broader range of users than strictly the subscription list. Now, even if a member of the public has physical access to a library, they may have to present digital credentials to acess information. PDFs and other digital media contain watermarks that allow rights holders to trace content back to an individual user and inhibit sharing.

Fair use is defined economically. If copying does not reduce the market value of the copyright material, and the copyright holder is not able to track and bill for such copying, then it is fair use. With modern information retrieval, finding copies is trivial and inexpensive, and micro commerce technology makes it possible to bill for almost anything, even if the charge is only a few pennies. As a result, the domain of fair use is shrinking dramatically.

The concern is that rights holders will use these new extensions of copyright to paralyze whole areas of commerce. For example, medical practice is based on implementing procedures and protocols published in copyright articles. Every time a physician or medical student does a Mini Mental Status Exam, they are copying the questions in that exam as they ask them to the patient. The exam gained popularity as an easy standard assessment, and for a generation (>20 yrs) after it was published, no one asked for any payment or royalty when the test was used. In the new era of digital rights, the copyright holders are asking for and receiving $1.23 every time the test is used. This is just one example, but the reality is that copyright trolls could go back through the literature and find thousands of similar examples where a physician order replicates a conclusion published in a copyright article and demand payment each time the order is written. Practicing medicine in this environment would be burdensome at best and would potentially set physicians up for significant liability. Given the near century life of a copyright, it will be many generations before medicine can be practiced without worrying about these issues.

You have some unusual views of copyright. First, you can’t copyright ideas, only their expression. Patents cover ideas, and that’s another whole kettle of fish. If you want to talk about how restrictive the patent world can be, and how universities exploit this (even taxpayer-funded inventions), let’s talk patents. But that’s not copyright. Second, fair use is an affirmative right — you have to defend it if you invoke it, you have to affirm that you have it; it is not passively granted to you by a lack of commercial damage or anything like that. The domain of fair use was just upheld in the Georgia State case, and it was pretty precisely what everyone thought it was. I don’t see where your concerns are coming from.

The Mini Mental Status Exam anecdote comes from the New England Journal of Medicine

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1110652 When a physician writes a set of medical orders based on a clinical guidelines published with copyright, they are inevitably copying those guidelines, and there certainly is precedent for applying copyright to clinical guidelines (see for example http://www.ahrq.gov/news/gdlcopyr.htm ).

In the Georgia State case the judge strictly limited the portion of an item that can be copied to less than 10% of the content and suggested that if the publishers offered convenient, reasonably priced systems for pay to access book excerpts online, they may be more successful in claims against e-reserves. Exactly what constitutes “reasonable price” for access was not addressed.

Copyright and the definition of fair use continue to be evolving areas of law. The concern is that essentially all of modern medical science is covered by copyrights that will endure for many decades. As technology improves, tracking and payment systems will make it possible for publishers to monitor and bill for essentially all forms of information access and information use. As you point out, fair use is an affirmative right. Nor is ignorance a defense against copyright infringement. Physicians do not routinely assert fair use in copying clinical guidelines into medical orders, but they are copying. Thus a substantial body of infringement liability may be accumulating. Given the litigious history of the publishing industry, concern on the part of users is prudent.

Yes, the MMSE is a story of people who made something that worked, then decided to cash in on it, and it’s been compared to a “stealth patent,” which is when the IP holders wait until something’s really popular, then assert their rights. It’s kind of tacky, in my opinion, but perfectly legal. And to extend the story, the company holding the MMSE copyright is now asserting rights over the “Sweet 16” alternative as well, forcing it to be taken down from the Internet. But that’s how the world works. The alternative is that physicians get to use something someone else created at no cost, but charge for their time and get reimbursed for administering a mental status test. Surely some share of that should go to the people who created what the physicians are finding so valuable. The cost of using the MMSE was $1.23 per test, so there is a price, and it’s pretty reasonable, actually. Is it worth $1.23 to find out if your relative is demented? Is that too much? One benefit of the creators exerting copyright protection is that they’ve made translations available in French, German, Dutch, Spanish for the US, Spanish for Latin America, European Spanish, Hindi, Russian, Italian, and Simplified Chinese. Maybe the incentive worked to make the test more widely available and used?

Copyright has a limited role in the world. It’s not a lock that can’t be picked. It requires either fair use (non-commercial, limited, etc.) or a reasonable fee to reward the creators of things the user obviously finds valuable. What’s wrong with paying someone for something you find valuable? Isn’t that how you’d want to be treated? The AHRQ site lists exactly how to get the rights, and often these can be had on a blanket basis. Most rights administrators are pretty reasonable. So I’m not sure a phone call and a discussion equate to a worrisome barrier to use, nor does a fee that’s commensurate with some level of value derived from the use.

There are plenty of people who want to weaken copyright, but you’ll find they often have financial motivations of their own.

If the inventors of the MMSE had patented the idea of their test, they would have had ample time to profit from their invention, but the patent would have expired more than a decade ago. By pursuing the Sweet 16 test, they are using copyright to block alternative and independently derived implementations of the idea. The courts have ruled in their favor, establishing precedent for a disruptive shift to restrict the use of intellectual property from patents with a lifetime of “only” 20 years to copyright which endures for 70 years after the death of the author.

In fact, as the NEJM article notes, demand for royalties has decreased the use of this once standard test, not increased it. This disrupts medical care because patient care extends over decades. If the patient had an MMSE score of x in 2001, a Sweet 16 scor of y in 2006 and yet another mental status exam score of z in 2012, are they showing an abnormal decline in function?

Unlike trademarks, a copyright holder does not have to assert the copyright in order to maintain it. Further, copyright can be asserted over work that was once in the public domain (http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/19/business/public-domain-works-can-be-copyrighted-anew-justices-rule.html). There is a place for copyright in commerce and society, but the changes in copyright law being driven by some parties with highly one sided interests may be quite disruptive for the rest of us.

It can be equally argued that Congress extended fair use in the 1976 Copyright Act beyond anything that the courts had previously recognized. One of the staunchest defenders of fair use today, Kenneth Crews, admitted as much in his book about copyright. Never before Congress added the words “multiple copying” to Section 107 had there been a case where what Judge Evans in her ruling in the GSU suit called “mirror-image” copying been held to be fair use. Photocopying, of course, is just that kind of copying, substituting for a printing press.

There is one additional element that might not be called “disruption” but is more like a “crunch.” For decades, I think statistics will show that the rapid increase in academic journal prices, and the number/size of academic journals, was fueled by shifting over funds from the library book budget to the journal budget. During the period I am guessing, from personal experience, 2006 – 2008 this shift in funds went as far as it could go. With the advent of ebooks, there may be more push-back to maintain some reasonable size for the library book/ebook budget. I agree with all of the above points that we’re not seeing a disruption in traditional subscription journal publishing model, but we may be seeing a crunch in its previous rapid rate of expansion/price increases.

On the market side I see a potential bifurcation. It is estimated that roughly 60% of authors publish only one paper in their lifetime, while 80% publish three or less. They do not dwell in the Publish or Perish environment. These folks might well prefer a low hassle gold OA publishing route. So might a bunch of potential authors who presently do not attempt to publish, because of the high hassle factor, like me for instance.

There is no clear market force driving a broad adoption of mega-OA approaches.

Library budgets?

I think it’s a bit inaccurate to say that the current academic publishing market is “one of users and readers” since readers by and large don’t make purchasing decisions; librarians do.

I think academic publishing has largely avoided the market-driven disruption that music and trade publishing have had to deal with because of our intermediated economics.

The ideology of “free” is highly disruptive to the music industry because it transforms paying customers into non-paying customers and, as far as I can tell, seems to have (for good or bad) permanently altered consumers’ feelings of how music is valued in the marketplace.

But readers of academic journals are already non-paying customers (from their own POV); they log on to JSTOR or whatever and it is effectively free to them because the library already paid for their access.

I wonder, then, what happens when people of my generation and those even younger, who are deeply influenced by the economic ideology of “free,” become deans of libraries. Does that change the libraries’ purchasing decisions? I don’t know.

Librarians are usually purchasing based on what their users say they want and need. If you aren’t publishing something the end-users want, a librarian will probably think twice before subscribing to it. So I think it’s accurate, although as you note it is intermediated. And you’re absolutely right — because universities are providing so much for free to students, faculty, and staff through site licenses, it has essentially devalued information perceptually. And that’s a more corrosive problem.

I guess it was accurate enough for the point you were making about the possible shift to the author as “customer” instead.

Thinking about it more, I actually think the rise of site license online access has been a disruptive innovation:

In the days of only print, a journal could sell an institutional subscription to a university’s library, but they could also sell individual subscriptions to individual faculty members who wanted their own copy.

For online access, though, there is no reason for a faculty member to buy an individual subscription if they already have institutional access: they don’t have to go to the library to get it, they don’t have to “share” the one copy that’s at the library, etc.

I suspect that this is part of what’s driving institutional subscriptions up faster than inflation: journals are now having to get all of the money that they used to get from an institutional subscription plus a number of individual faculty subscriptions from just the institutional subscription.

Library budgets are certainly fueling the drive for government mandated OA. Witness the “ruinous” Harvard hyperbole above. SPARC is a big player in the government game.

But I imagine they have little to do with the market forces behind gold OA as a business model. Much of the confusion flows from failing to distinguish these two different issues. I do not see librarians pushing their research colleagues into gold OA, just to save their own budgets, but maybe I have missed the show. Where are the researchers chanting “hey, hey, we want to pay”, with librarians providing the signs and refreshments? Just kidding of course, sort of.

It’s not a matter of librarians “pushing their research colleagues” to want gold OA at all, but rather a journal/society deciding where they think they can get the most money or where they’re most likely to be able to get any money.

The possibility I see is if library budgets dry up enough, a journal that has seen its subscription base drop significantly may feel that gold OA is a better way to pay for the journal’s production expenses. Obviously this is a decision that would depend entirely on the specific financials of the journal/publisher/society and also the funding situation of the (sub)discipline, but it seems at least to be a possibility.

This economics might also affect the decisions of start-up journals, which, unless they’re from a big publisher and part of its “Big Deal,” might have a hard time getting libraries to subscribe in the first place.

I suspect that when faced with the unfortunate decision to cut a subscription, a librarian isn’t thinking about where that journal/society might have to go to replace the lost revenue.

Good model, but library budgets are not drying up, merely possibly capping. That is a big difference, model wise. In any case, what I see at this point is a flood of speculative new gold OA journals, so big it is swamping DOAJ. How this swamp fares is very important.