On Thursday, Science journalist John Bohannon (some of you will recognize his work organizing the annual “Dance Your PhD” Contest) released the findings of the largest study of the peer review systems of open access journals, and it didn’t look good: The majority of publishers tested in his study accepted a bogus scientific paper, most with little (if any) peer review.

Critics of the investigation were quick to point out that the experiment lacked a control group–a group of subscription based journals to which the open access journal group could serve as a comparison. The lack of a control means that it is impossible to say that open access journals, as a group, do a worse job vetting the scientific literature than those operating under a subscription-access model. The study does reveal that many of the new publishers conduct peer review badly, some deceptively, and there is a geographic pattern in where new open access publishers are located.

Some critics assailed Bohannon (and Science) for undertaking such a study in the first place, accusing Bohannon of “drawing the flagrantly unsupported concluding [sic] that open-access publishing is flawed,” using the opportunity to come up with an equally unsubstantiated conclusion, that “peer review is a joke,” or arguing that by publishing the piece, Science failed in properly conducting its own peer review (ignoring the fact that Bohannon’s article was a piece of investigative journalism published in a Special News section). Science does indeed give the article credibility, inasmuch as Nature and The Lancet and Physics Today conveys credibility upon news reported by its journalists.

While I agree that Bohannon missed a great opportunity to include a control group in his study, this is not grounds to dismiss his investigation completely. Previous attempts to unearth unscrupulous publishers or a flawed peer review process provided little more than anecdotal evidence. Bohannon approached and documented his investigation systematically, and while the lack of a control group clearly limits what can be concluded from his study, much can be learned.

First, there is evidence that a large number of open access publishers are willfully deceiving readers and authors that articles published in their journals passed through a peer review process–or any review for that matter. It is simply not enough to declare that a journal abides by a rigorous review process.

Similarly, the results show that neither the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), nor Beall’s List are accurate in detecting which journals are likely to provide peer review. In spite of an editorial and advisory board on the DOAJ, nearly half (45%) of the journals that received the bogus manuscript accepted it for publication. And while Bohannon reports that Beall was good at spotting publishers with poor quality control (82% of publishers on his list accepted the manuscript). That means that Beall is falsely accusing nearly one in five as being a “potential, possible, or probable predatory scholarly open access publisher” on appearances alone.

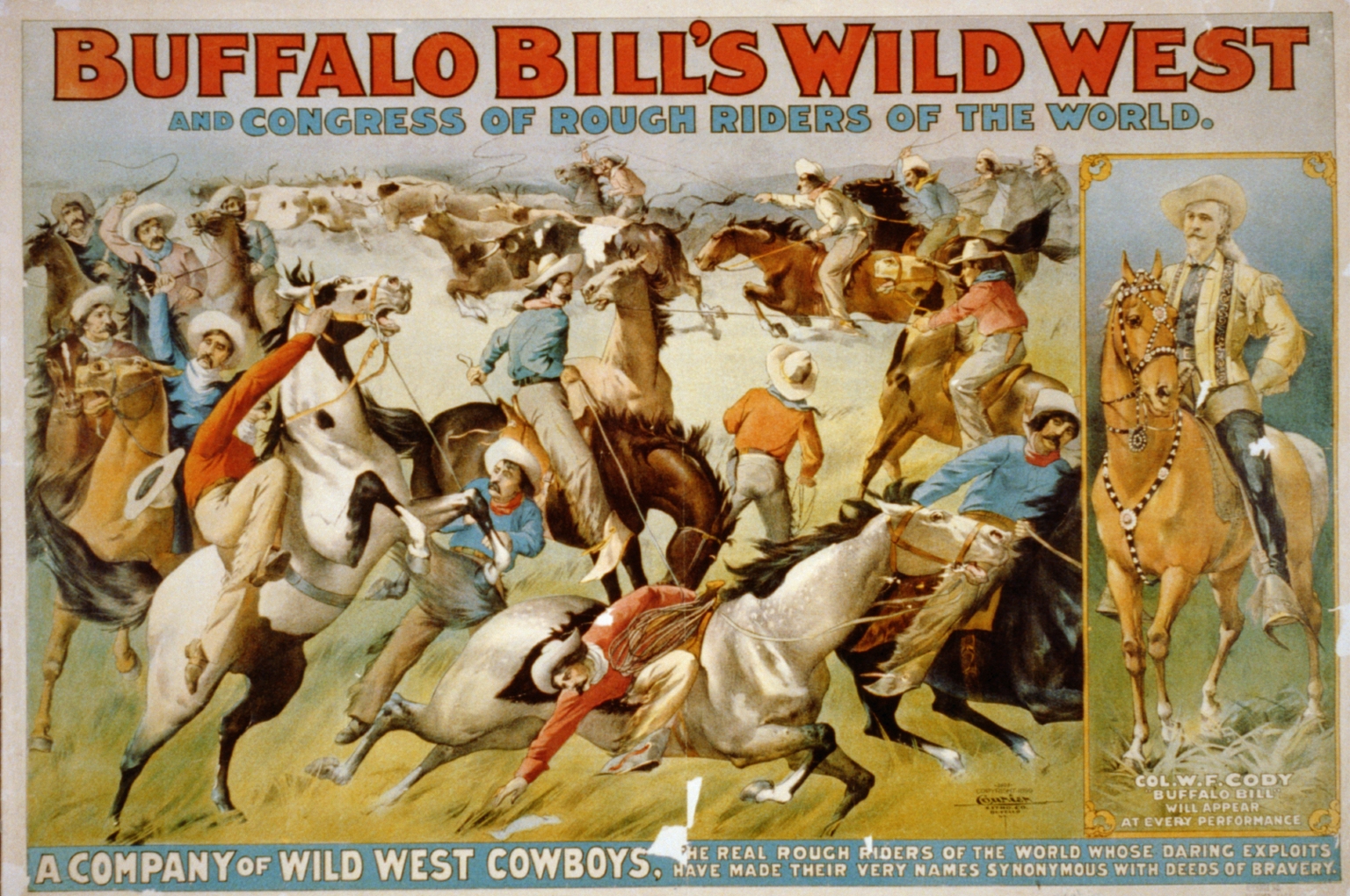

It would be unfair to conclude from Bohannon’s work that open access publishers, as a class, are untrustworthy and provide little (or no) quality assurance through peer review, only that there are a lot of them, their numbers are growing very quickly and that many willfully deceive authors and readers with false promises, descriptions copied verbatim from successful journals, and fake contact information. Bohannon refers to this new landscape as an “emerging Wild West in academic publishing.”

New frontiers eventually become tame when groups of civil-minded individuals get together to develop laws and norms of good conduct. In the publishing world, there are organizations like COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics), and OASPA (Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association), both of whom include, as members, several of the deceptive publishers revealed in Bohannan’s investigation. The real test will be to see how these membership organizations react to the investigation. If they are to uphold their credibility, they will need to censure and delist the offenders until they can provide evidence that they are abiding by the guidelines of their organization. This means stripping these publishers of the logos many display proudly on their web pages.

It also means that the DOAJ, if it is to remain a directory of open access journals that uses a “quality control system to guarantee the content” must provide stricter guidelines and require evidence that publishers are doing what they purport to be doing. The DOAJ may also require independent auditing to periodically verify a publisher’s claims. It is simply not enough to take promises of quality control on word alone. Finally, it means that librarian, Jeffrey Beall, should reconsider listing publishers on his “predatory” list until he has evidence of wrongdoing. Being mislabeled as a “potential, possible, or probable predatory publisher” by circumstantial evidence alone is like the sheriff of a Wild West town throwing a cowboy into jail just ‘cuz he’s a little funny lookin.’

Civility requires due process.

Discussion

128 Thoughts on "Open Access "Sting" Reveals Deception, Missed Opportunities"

Thanks for this, Phil — much more even handed than I was bracing myself for.

I think you underestimate the flaws in Bohannon’s piece, though, and give him much to much leeway by calling the piece “journalism” rather than research. Journalism in the journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science has a responsibility to be scientific, and Bohannon’s piece fails that test in multiple ways.

His sampling approach — drawing from Beall’s list — is classic fishing-trip behaviour: actively looking for journals that we already know (or at least suspect) are not doing the job right. Again that backdrop, the failure to provide any control group of subscription journals is not just weak, it’s fatal. A corresponding control group would be drawn in part from a pre-existing list of known-bad subscription journals, analogous to Beall’s list. Or, more appropriately, Beall’s list would have been left strictly alone, and the sampling done similarly for both OA and subscription groups — for example, by using all the journals indexed in PubMed, Scopus, or some other trusted index.

Bohannon gives his reason for not doing this in the Retraction Watch piece: “I did consider it. That was part of my original (very over-ambitious) plan. But the turnaround time for traditional journals is usually months and sometimes more than a year. How could I ever pull off a representative sample? Instead, this just focused on open access journals and makes no claim about the comparative quality of open access vs. traditional subscription journals.” Frankly, that is pretty contemptible. Designing a proper study would not have been difficult, and it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the improper design was driven by a desire to get finding that could be spun into a “story” rather than to find anything out.

In short, the story is not science, and doesn’t belong in Science. Although in light of Arsenic Life and other such debacle, maybe that’s exactly where it belongs. The AAAS have certainly done their credibility no favours here.

I think it’s important that we not confuse three different questions here, one of which the Bohannon article answers well and two of which it doesn’t.

The question it answers well is: does there exist a substantial number of sleazy OA publishers? (The answer is yes, and perhaps more of them than we suspected; therein lies the usefulness of his study.)

The first question it does not answer well is: Are sleazy publishers disproportionately represented in the OA marketplace?

The second question it does not answer well is: Are OA publishers more likely to be sleazy than toll-access publishers?

I agree with those who wish that his piece had been better structured to address the latter two questions. That doesn’t change either the fact that it does answer the first question, or the fact that the first question is an important one — regardless of what one thinks about OA. Fans, foes, and agnostics alike should all welcome sunshine on this issue, it seems to me.

You’re right, Rick, about the three questions. Unfortunately, the one that this work was informative about was the one we all knew the answer to already. I’m really struggling to see how it adds any new information. At best, it’s a terrible missed opportunity.

In the mean time, the prose of the article, Science’s press release, and even the URL of the supplementary information (http://scim.ag/OA-Sting) all carry the same FUDdy message: that this is about open access. Given Science‘s own position as a premium subscription venue, it’s hard not to see this as getting the result they wanted because they designed for it.

What is understated in this article is the definition of reader. While subscription journals are for the most part targeted at discerning specialists or at the very least undergrad students, open access journals are by design meant to be read by anyone. When a flawed paper shows up in a legitimate-sounding OA journal, everyone has access. Would a lay person have any idea that the information found in a Google search is not trustworthy? At the very least, this Science piece illustrates how these unscrupulous journals are undermining the purpose and value of open-access journals.

REALLY???? Just because a paper is OA means a lay person can read and understand??? So I now can understand papers in high-energy physics, molecular genetics, theoretical math, etc., etc.

From the Finch Report:

“The principle that the results of research that has been publicly funded should be freely

accessible in the public domain is a compelling one, and fundamentally unanswerable.

Effective publication and dissemination is essential to realising that principle, especially for

communicating to non-specialists.”

I was basing my comments on the current drive to have publicly funded research available to those who paid for the research.

The Finch Report “principle,” quoted above, reminds me somehow of Timothy Leary’s dictum: “You have the right to be your own psychopharmacologist” underlying his more famous “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” It’s a nice fantasy, but not of the real world.

Pointing out that Science hadn’t carried out peer review on this article is reasonable — I agree that it’s in a journalist section, but the research *could* have been well designed and wasn’t.

As it stands, I think that the conclusion that many OA publishers are “willfully misleading” is misleading; he has a biased sample set. Consider this analogy; is it reasonable to conclude anything about your article on the basis that you use WordPress, and many WordPress sites have poor journalistic standards?

Thanks Phil for a fair review of the article.

First, anyone can put up a web site and call it a journal. To attract legitimate authors in any number publishers have to develop a reputation of providing quality service including legitimate peer review. I am not saying some of the sleazier journals do not attract some manuscripts but I don’t believe in great numbers. I expect in some cases because there are sleazy authors desperate for a quick publication and unfortunately some authors probably get fooled though I suspect it is relatively rare. In general the sleazier journals publish very few articles. Several years ago we reviewed every journal in the DOAJ listed as charging APCs from a publisher with at least 2 journals and a roughly 10% sample of the long tail of single journal publishers.

Solomon DJ, Björk B-C. A Study of Open Access Journals Using Article Processing Charges. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 63(8):1485–1495.

I went back and checked the data (this is not in the article) 78% of the articles in those journals were in journals either in the Journal Citation Report or Scopus or both citation indexes. In general the legitimate journals have lots of articles and the sleazy ones do not.

The DOAJ, OASPA and COPE all have criteria but checking if a publisher has a peer review process and actually checking if it is implemented in a legitimate way are two different issues. It doesn’t surprise me that some journals that apparently do not do real peer review were able to make it into these three organizations. Real auditing would help but would be very expensive.

One simple thing legitimate OA or for that matter subscription journals can do to address any question of competent review is to document the whole peer review process. BMC has done this for years. Anyone can go in and look at all the reviews, and editors comments, the authors responses and each set of revisions. This can be done with or without naming the reviewer or leave it up to the reviewer whether or not they want to remain anonymous. It’s a simple way to avoid any question of the type of review done by a journal.

“BMC has done this for years. Anyone can go in and look at all the reviews, and editors comments, the authors responses and each set of revisions.”

Only for a small number of BMC journals, though, I think, not all of them.

Perhaps not all of them and I haven’t kept track but I believe it is true (or at least was a few years ago) for the original BMC series journals which I believe were 80 or 90. My point is this is a good way to ensure transparency in the review process and ensure for anyone who cares to look that it was done well (or not). I can’t think of a single reason why this is a bad idea for either a OA or subscription journal when it is only done for the articles that are eventually published and reviewers at least have the option of remaining anonymous.

The sad thing is – Science had the chance to publish much more overarching, actual peer-reviewed data on the quality of the science published in scholarly journals, but chose to reject its publication, in favor of this un-controlled anecdote.

That preference for obvious anecdote over hard data makes the journals accepting the bogus paper look not so bad in comparison to Science Magazine.

While I am deeply charmed by Science’s spunk, I do also think that they really should have referred to previous pranks that have resulted in randomly-generated fake papers being accepted to journals and conferences.

I personally adore SCIgen, a free online paper generator that will churn out any text you wish; visit their webpage to note a running updated list of places where SCIgen papers have been accepted – since 2005, when open access was less of a hot topic.

Other charming examples are MathGen and a grant proposal generator – this year marks the acceptance of a MathGen paper to a reasonably prestigious paid-subscription journal. Science really should have done a literature search and cited previous work!

Excellent items. Add to this the Phil Davis paper which was computer-generated gibberish, and accepted (but not published, as Davis withdrew it quickly) by an OA journal.

A summary spreadsheet of the journals, publishers and manuscript decisions can be found as a data supplement:

Of 157 journals that accepted one of Bohannon’s papers, 3 are currently listed in Web of Science. Of 98 that rejected one of the papers, 36 are currently indexed in Web of Science. Many of the titles in the study have never been submitted for review in our indexes, others are currently in evaluation or have been rejected; at least one was previously covered and dropped.

OASPA’s response to the article in Science is now available at http://oaspa.org/response-to-the-recent-article-in-science/.

I’m glad the OASPA will be checking with its members whose journals accepted the article to find out why it was accepted, but I find the OASPA’s complaint about the study focusing on fee-based OA journals only and not including TA journals a red herring. TA journals have no economic motivation to accept flawed articles the way fee-based OA journals do; indeed, they have a real disincentive to do so. Given this crucial difference, it stands to reason that any comparative study would find many more OA journals with poor or nonexistent peer review policies than TA journals. Do we need to prove the obvious?

P.S. By the way, was there any criticism of the Sokal hoax for not being a more systematic study?

Sandy Thatcher — the hypothesis that economic motivation is the major factor involved here remains to be tested; his hypothesis may be obvious to *you*, but the lack of appropriate controls in Bohannon’s sample means that this hypothesis hasn’t been proven.

Why should we require this proof? Because it’s not necessarily a given that “TA journals have no economic motivation to accept flawed articles”. Given the very complicated bundling deals that TA journal publishers sell to libraries, there might very well be a big incentive to pad what would otherwise be a small bundle with a few sham journals to make the deal look better. (Think of TV cable channel bundles — there are plenty of folks who choose the deal with 500 channels because they feel it must be better than the deal with only 50.)

As for criticism of the Sokal hoax, you may be interested to see e.g. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sokal_affair#Academic_criticism.

What is a sham TA journal? Do you mean low quality?

Yes, but I think it’s also possible for a literal sham journal (= no quality control whatsoever) to exist with a subscription model, as part of the padding that a publisher might add to a bundle.

Could you point out some examples of these sorts of journals?

As noted in another comment, I’m not sure your reasoning works as far as bundles. If I’m a publisher with a bundle of excellent journals, what’s the advantage in adding that padding? If I want to bring in more revenue, I’m probably better off just charging a higher price for my existing bundle than creating journals that ruin my reputation and that readers don’t want and librarians won’t pay extra for.

Agreed. I’ve never heard of a commercial TA publisher deliberately setting up droves of new “sham/padding” subscription journals. That wouldn’t make sense. In “packages” the incremental cost of new journals is tiny. One British librarian told me that the annual cost of their average

journal in a giant package was about $5 apiece, as opposed to $500 apiece when subscriptions were taken out one-by-one.

In addition, what exactly does a TA publisher do, in terms of setting up a sham/padding contract with a potential academic editor? The entire proposal smacks somewhat (unintentionally) of conspiracy thinking

I don’t have an example of this sort of journal (nor, in my defense, did I claim to have). As I said in my reply to you (David) further below, “I’m only responding to those who seem to be asserting that low-to-no quality control at a TA journal is impossible, and that this is (patently) obvious — and thus undeserving of a “sting” to find out the answer — because of the different financial incentives that define the TA business model as opposed to OA.”

I agree that in a rational world, things would work exactly as you say here. But I do think that a non-conspiratorial scenario is possible here (to respond in part also to Bill’s point). A TA publisher does not have to *knowingly* set up journals with low-to-no quality control; there just needs to be some incentive to have more journals (insofar as this means more content). That incentive exists to the extent that bundle pricing needs to be justified, which can translate into some more proposals for new journals being solicited and/or accepted by the publisher (where the intent to have low-to-no quality might lie with the scholars proposing those journals — they have incentives, too!).

Is this not even possible, do you think?

As one of the co-founding members of OASPA I agree with this blog post that OASPA needs to draw consequences from this incident.

I hate to be right on this occasion but I saw it all coming over 5 years ago, pre-Beall and pre-OASPA… Read http://gunther-eysenbach.blogspot.ca/2008/03/black-sheep-among-open-access-journals.html and also read the comments section, where the idea of an open access publishers association was first discussed (and the problems associated with it). Organizations that claim to do quality assurance (DOAJ, OASPA) should maybe introduce random checks by asking its members to produce peer-review reports and name the reviewers of already published articles.

The Bohannon study has some limitations and flaws (and even some of the data were missing/incorrect, now corrected as result of my blogpost about the Bohannon study at http://gunther-eysenbach.blogspot.ca/2013/10/unscientific-spoof-paper-accepted-by.html) but the resulting list of shady publishers is interesting. Also interesting is that most of the bank accounts lead back to Nigeria and India. One is reminded of the Nigerian wire fraud scheme (where you get an email from an alleged lawyer promising inherited money, but you have to pay the lawyer first to get it). Now, does anybody conclude from these Nigerian wire schemes that most lawyers are scammers, or that the fee-for-service model for lawyers encourages fraud? It would be equally absurd to draw these conclusions for open access publishers.

Another aspect that is often forgotten in this entire debate is that the “pay on acceptance” Article Processing Charge model is not the only model for gold OA. JMIR Publications has (and always had) an alternative membership scheme, as well as submission fees, and if the community concludes that APCs encourage fraud/volume, then perhaps it makes sense to shift to other modes of payment (in our case, increasing the submission fee and getting rid of the APF payable on acceptance, or more aggressively marketing our membership scheme). JMIR Publications offers both alternatives (membership OR APF on acceptance), and most researchers still choose the latter. Academics have it in their own hands… In the public debate “open access” is now muddled with “taking money to publish an article”, which is the most popular payment option, but which is not necessarily how all OA publishers operate or would like to operate. Unfortunately, Bohannon excluded journals that charge submission fees. But my hunch is that researchers would hate the idea to pay and to be rejected more than to be accepted and to pay – but perhaps this will slowly start to change post-Bohannon.

(Full disclosure: I am publisher at JMIR Publications, a leading open access publisher, and co-founding member of OASPA)

DOAJ’s response to the Science article is now available: http://www.doaj.org/doaj?func=news&nId=315&uiLanguage=en .

For the record, DOAJ has been working on stricter criteria for the best part of this year. A first draft was released for public consultation on 12th June (http://www.doaj.org/doaj?func=news&nId=303&uiLanguage=en) and a revised version was released in September (http://www.doaj.org/doaj?func=news&nId=311&uiLanguage=en). The revised criteria specifically addresses peer review.

Dom Mitchell, DOAJ

In reply to the comment that it is possible for a TA subscription publisher to solicit proposals for low-quality (“sham”) journals: yes, it is possible but highly undesirable. Yes, a subscription-based publisher can solicit and accept proposals for journals by obviously untalented academic editors with poor credentials, and anticipate a weak manuscript flow of poor quality articles. It is possible but highly undesirable. Such “Debilitated Journals” would have poor one-by-one subscriptions as a financial base; would detract from the publisher’s brand strength; and would not grow in terms of attracting high quality articles. Such journals would weaken the large publisher’s over-all Reuter’s citation score for the entire bundle. The publisher may be better off acquiring an smaller publishing house which already has an excellent subscription base and high-quality journals.

So yes, it is conspiratorially possible to solicit and launch a slew of low-quality TA “Debilitated Journals” but especially nowadays with vanishing library budgets, most likely financially undesirable.

I cover some of these issues in prior Kitchen articles:

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2013/06/20/doaj-in-transition-interview-with-lars-bjornshauge-managing-editor/

and

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2012/10/03/the-new-wave-of-gold-oa-journals/

Another interesting article in the same issue of Science is, “Scholarly Communication: Cultural Contexts, Evolving Models,” by Diane Harley. She describes how established scientists, influenced by strong tenure and promotion committees, are very conservative in their choice of journal outlets for their work. They tend to stick with the tried and true, established journals with good reputations.

I wonder if the explosion of journals and articles may be pushing us into a publishing ecosystem where a relatively small number of trusted journals get the vast majority of top research. The rest are left to fight for the crumbs and can be safely ignored by busy scientists. It’s kind of like the New York Times vs the tabloids. The Gray Lady will continue to have influence because enough discerning readers trust its reporting, but the tabloids have higher circulation.

Harley’s article is comforting to old-line journals. But, with all the scams out there, this is a scary time to start a new journal if you’re serious about good science.

Signaling theory posits that in a growing marketplace of academic papers, where quality is not readily apparent and readers have limited time, brands become stronger heuristics. The end result is indeed the opposite of what many sincerely hoped would happen as a result of lowering the barriers to entry for new journals: Trusted brands will become more trusted, the rich will be come richer, and small will have an increasingly harder time getting noticed.

Our society’s journal enjoys a very strong connection to our conference program, a major branding effort. A lot of our authors have been to one of our conferences, know who we are, and probably have talked to our leaders, staff, and editorial team. A personal touch goes a long way in attracting top authors.

While I agree a control group would have been nice, Bohannon has nonetheless uncovered fraud on a massive scale. That 157 journals accepted this paper is a scandal. That at least one publicly traded company is involved is a scandal. And the fact that many commentators, including well-known scientists are trying to discredit the work because they think it casts a poor light on open access is a scandal.

While it would be nice to know how the OA journals stack up against subscription publications, that doesn’t obviate the fact that 157 journals are engaged in outright fraud — not simply shoddy peer review. It is outright fraud as it is evident that many (all?) of these publications are claiming to be peer-reviewed journals, and accepting money for their validation as such, when they are no such thing.

There is also cause for more than a little concern regarding those journals that reviewed and rejected this paper. While these journals have a working review process in place with conscientious reviewers, they obviously didn’t bother to do a basic administrative review of the manuscript when it first came in to validate that the institution and authors were real people. When a paper comes in from authors and institutions not in a journal’s database, it usually triggers a little extra scrutiny — at least a quick search of PubMed or Google to see if the institutions exist and if the authors have ever published anything before.

The comparison to the arsenic paper that Science published is therefore a false equivalence. In the case of the arsenic paper, the researchers and the institution were real. Moreover Science conducted peer review. That was a case of shoddy peer-review. This is a case of widespread fraud in the case of the journals that accepted this paper without review, and a failure of basic administrative review in the case of journals that sent this out for review before validating that the institutions and authors were real.

Great stuff Michael. Cherry picking the “Arsenic is Life” paper and other high profile cases as poor peer review as proof that “peer review is a joke” (Eisen) is too easy. I believe around 2,000,000 articles across 24,000+ peer reviewed journals were published last year. Of course some mistakes will occur. But overall, an ethical, rigorous peer review system is still (IMO) among the most valuable services ANY journal can offer.

“While it would be nice to know how the OA journals stack up against subscription publications, that doesn’t obviate the fact that 157 journals are engaged in outright fraud”

What gives you the right to say that Science gets to made a mistake and these journals participated in fraud? Is it fair to say missing an obvious flag on an administrative review is fraud and missing blatant scientific errors (I am going on second-hand information here since it is not my area of expertise) is just a mistake?

My guess is that most of these journals do not do real peer review but to automatically dismiss them as participating in fraud while giving Science a pass seems pretty chauvinistic to me.

If you want to talk about cost, these journals tend to charge at most a few thousand USD paid by the author. I don’t know what it costs to publish an article in Science but Nature’s editor has publicly claimed it costs 30,000 to 40,000 USD for them to publish an article and Science seems to be essentially the same type of journal. Somebody paid to publish the apparent crap in this arsenic paper and that somebody happens to be all of us.

30-40k for one article. Are you sure? PeerJ can do it for $99.

In all seriousness, that number sounds hugely incorrect. 10k? Perhaps with the biggest PR push available. $5k possibly. $3k is more likely.

Thomas Hilock – My jaw dropped too but it is a direct quote in Nature News.

Has anyone pointed out that one of the reasons the “traditional” journals take longer to conduct peer review, something they are often criticized for and the reason given by Bohannon for leaving them out, is because conducting an ethical, rigorous review process takes longer? (DUH). I do wish this “sting” took a little longer to include more traditional journals, because, as naive as I may sound, I believe that most (certainly not all) would not have fallen for this. Having that info would have made this conversation even more valuable.

Adam, having 30 years in the “commercial” journal industry, I’d have reservations about a view that most traditional journals, vs OA journal, would have fallen for a “sham” article. The traditional journals (broadly speaking) just don’t have the motivation. It is so costly really to set up a really traditional subscription-based journal, and to have a paid staff in-house that processes each typeset, published article. The # of articles per year is tightly budgeted. In other words there is a real cost associated with each article published. With an OA journal lets say of “loose calibre,” they have a core financial motivation to accept and publish as many articles as possible. It is an entirely different economic system. This said, the Science article above was shocking in its report that a small number of subscription-based journals did in fact accept the article. This is truly demanding of further scrutiny and concern.

I would like to be a fly on the wall for the Board meetings of the major publishers cited in the article. Who is holding the CEO’s feet to the fire?

The major publishers have 100’s, if not 1000’s of journals and some of them will be society with completely external editorial boards. This isn’t a CEO issue, it’s an editorial issue at either the journal, or the portfolio level.

Sorry, no, that’s not good enough. If you’re going to put your name on a journal as its publisher, you’re putting your reputation on the line. Either exercise adequate oversight, or don’t take on more journals than you can handle.

I didn’t say no one is responsible. I said the CEO is not responsible. If an Apple app is buggy do you expect the CEO to step down? No. If the share price falls two 1/4 of the value, then the CEO should be worried.

My point is not that it is fine, but let’s not make stupid claims that a CEO should be held accountable for one paper in one journal that they may never have even heard of.

Who is responsible then? Where does the buck stop? When Apple put out a buggy product (Antennagate), Steve Jobs sure as hell did address the issue publicly and tried to make good by offering a free bumper case to purchasers who wanted one.

If not the CEO, then who?

For the record, Apple fired the executive behind Antennagate:

http://news.softpedia.com/news/Apple-Fires-Exec-Responsible-for-the-iPhone-4-Antenna-Report-151189.shtml

Will someone be held responsible here?

And “if you’re going to put your name to a journal”… You won’t find many CEO’s name on a masthead.

So your point is that no one at a big corporation is responsible? They’re blameless and can get away with whatever they want?

Where did I say that? I said this was not a CEO issue and suggested the responsibility belonged with the journal or the portfolio. Don’t put words in my mouth.

You even made my point for me re: it not being the CEO. Did Cook or Jobs step down? Even after Antennagate, Mapgate etc…

Yet the CEO in each case addressed the problem and took responsibility. Joe’s original comment suggested that the boards of these companies should be “holding the CEO’s feet to the fire” defined as:

http://idioms.thefreedictionary.com/_/dict.aspx?rd=1&word=hold+feet+to+the+fire

“to cause someone to feel pressure or stress”

Is that really a crazy response here? Is this such a trivial instance of fraud that is so unlikely to tarnish the company’s reputation that the whole thing can be handled at a very junior level? Should Elsevier, Sage and Wolters Kluwer just laugh this off?

I am not entirely sure of the exact relationship between any of the “outed” journals in question and the large companies named in the piece: Sage, Elsevier, Wolters Kluwer. My impression is that Elsevier has a services relationship, not a formal publishing relationship with the tainted journal. This gets tricky to untangle. A feature of service arrangements is that the service provider (in this case, Elsevier) has no editorial involvement with the client (in this case a tainted publication). Would we want it otherwise? Would we want Wiley or OUP or Cambridge to act as an editorial overseer of the various society publishers with whom they have relationships? At the same time, the clients share in the aura of the service provider’s brand. I don’t know the answer to these questions, but the problem is more complicated than the typical OA debate over good and evil. Nietzsche, anyone?

Bohannon was testing Beall’s hypothesis that this behavior is widespread in gold OA, with a strong positive result. No control group of subscription journals is needed for this test. But the next question is indeed one of the relative prevalence between gold OA and subscription journals. Bohannon may have a new career.

This ‘experiment’ tells you nothing about the general state of peer review in gold OA, journals. The sample seems to be heavily skewed towards suspicious journals and cannot be taken as representative for the industry in general.

Nor do I see Bohannon making that claim. If I suspect a group of my employees are stealing and I catch them at it I have confirmed my hypothesis, but this says nothing about the bulk of my employees. Bohannon’s selection method was designed to find the bad actors, not to assess the industry. But because OA is a political issue people are drawing overly strong conclusions, or they think others are.

Bohannon’s piece is certainly going to force the reputable organizations that were touched by this to take a close look at what they’re doing, but the overall impact will be limited because it’s just a one-off.

In most areas where maintaining quality is in the public interest (e.g. food safety), random inspections are the norm. Is there a need for an ongoing task force that routinely submits fake papers to all types of journal, and calls out the ones with slack quality control?

“Science” long ago entered journalism because publishing only research papers wasn’t meeting audience needs. This should be noted. Their journalism has proven both popular and effective, as have other similar initiatives in other major journals.

The “sting” here was exactly that — limited, sensational, and good copy. It’s not a study, and it was not peer-reviewed. It was a reporter pulling on a string and watching things unravel. It’s the kind of thing that should lead to a study, force accountability, increase awareness, and drive change. The sloppiness revealed at all levels via this sting is eye-opening. Some of us may be able to rationalize various aspects away, but when large publishers like Elsevier, SAGE, and Wolters-Kluwer are this evasive and unaccountable, while we also see problems with OA journals at the margins, we all need to seriously think about what’s going on here.

Journals that caught this paper are not “off the hook” either, as the paper was made to be easily caught. Some have applauded the journals that rejected it, but this was not a valid stress-test of strong peer review, just an easy way to detect token or absent peer review.

Was this a good sting? It was OK, could have been better. Did it reveal problems? Yes, and in more places than expected. Are these issue we as a community need to address? Definitely.

I would like to point out that the Journal of International Medical Research (JIMR), published by SAGE, did not accept the article submitted to it for publication as it stands. It was accepted subject to further editorial queries being answered to the satisfaction of the journal. This is clearly laid out in the correspondence with the author.

JIMR is a long-established, respected journal that has been publishing quality research for 41 years. It is JCR-listed and its rejection rate was 62.5% in 2012. Professor Malcolm Lader Ph.D., M.D., F.R.C. Psych., F. Med. Sci., Emeritus Professor, King’s College London is the Editor of the journal and has been for the last 25 years. It has a world class Editorial Board.

JIMR has operated a two-stage review process, specific to this journal. First, the editor performs an initial review of a submission and then, once a paper has passed this initial review stage, it is accepted subject to a detailed technical edit, which is undertaken by at least two experienced medical technical editors. It is not uncommon for articles to be rejected at this stage.

We are extremely concerned that a paper with fundamental errors got through the initial stage, and are taking steps to ensure that it cannot occur again, but are confident that the technical edit would have revealed the errors.

SAGE is committed to ensuring that the peer review and acceptance process for all our journals, whether traditional subscription-based or Open Access, is robust.

A fuller statement is posted on the SAGE website: http://tinyurl.com/jwldtgm.

David Ross

Executive Publisher, Open Access

SAGE

I continue blame science policy managers, as I did more than a decade ago, well before the OA revolution. In spite of their noble facades, it seems that the notion of “profitability” consumes managers of scientific associations, universities, and government agencies as much as it does commercial publishers.

(Undermining peer review. Society. 38,2:47-54. Jan./Feb. 2001)

Maybe the interesting issue of peer review coming under pressure is hijacked a bit by the OA vs. non-OA discourse. Quality peer review, or evaluation, seems to be a fundamental challenge across scientific publishing to discuss in light of output growth regardless of access models.

How is peer review/ evaluation organized to meet output growth, and how is good peer review/ evaluation incentivized? If good peer review becomes an increasingly scarce resource relative to increasing demand, do you think disruptive examples of more direct recognition and commodification of that personal service will appear?

Not to defend Beall per se, but is it fair to say that nearly one in five of the publishers on Beall’s list is wrongfully accused because they refused a bogus paper?

What this report highlights is a key difference in the business models between OA and Subscription. OA the money is front loaded. Accepted paper = profit, regardless of quality. Reviewed and unpublished paper = loss. Hell, if you look at PeerJ as an example, they want you to pay before you’ve even been accepted to ‘save’ money.

Whereas for subscription journals money is collected at the end. Accepted paper = no money, subscription = profit.

For a subscription to be paid it has to show continued value to the reader, OA does not. Therefore subscriptions have more motivation to review, edit, and publish good science. I would be very interested in seeing the same type of ‘sting’ done to subscription journals. I suspect they would fare better, but would certainly not be perfect either.

Actually, PeerJ is a particularly poor example here. Because of the membership model, they have no direct financial incentive at all to publish papers. Once they have my $99 for life, their most rational position is to reject without review everything I send to them.

They reason they won’t do that is because they’re trying to build a reputation. The same reason, in other words, that good subscription publishers don’t do exactly the same.

While your logic makes some sense, if an Indian journal named “American Journal of Biology” asked for payment before acceptance, we’d be calling it a scam.

The problem with your reasoning here is that it’s not readers who are the main subscribers to journals; it’s institutions, who are often essentially forced to accept large and expensive bundled packages of journals. The larger those bundles look, then (possibly) the more palatable they look to buyers. So there is the potential for incentives to be more front-end than back-end even for subscription journals.

I’m not sure that’s really the case, and some of our librarian readers may want to chime in. Which is more attractive to you, a bundle of high end, high use journals or a bundle that’s bigger, but has a lot of long tail low-use stuff padding it out?

I’m not sure of it, either, so we’re in the same boat. I’m only responding to those who seem to be asserting that low-to-no quality control at a TA journal is impossible, and that this is (patently) obvious — and thus undeserving of a “sting” to find out the answer — because of the different financial incentives that define the TA business model as opposed to OA.

I’m also being unfair to the role librarians play in making decisions about journal bundles, I realize, so I would also like to hear what librarians have to say about the *possibility* that low-to-no quality TA journals *could* be introduced into bundles to make them look a bit more attractive than a bundles that don’t include them — on the assumption that it might not be immediately obvious that these journals are low-to-no quality (which is exactly what we’re interested in finding out).

Speaking as a librarian, what makes a bundle attractive to me (and makes me likely to buy into it despite hating the model itself) is if it’s the most cost-effective way for me to give my patrons access to content that they actually need, and I generally measure cost-effectiveness in terms of dollars-per-download. (Yes, I recognize the serious limitations of this measure. But with limited staffing and tens of thousands of ejournals to manage, imperfect measurement is my only option.) So the size of the package itself matters relatively little, except as it has an impact on cost-effectiveness. A smaller bundle that consists entirely of high-use titles may or may not be preferable to a huge one that includes lots of low-use titles–it all depends on the total cost and the behavior of my patrons. As a wise colleague of mine loved to say: “We don’t pay invoices in percentages; we pay them in dollars.” The same is true of “value.” I don’t spend a lot of time trying to assess the pure value of a package. I look at actual usage by actual patrons, and measure how much we paid in actual dollars to support that behavior. So for me, the bottom line with Elsevier is that if we were to cancel our Big Deal with them and buy only individual subscriptions to those titles that get heavy use on my campus, we’d end up paying more per download than we do under the Big Deal. Res ipse loquitur. It’s ugly, but there are no pretty options available to us in the current environment.

I’m not saying that all librarians think this way, but I think most of us do (and perhaps more of us than will publicly admit it).

I don’t understand the above comment.

Large bundles are indeed prepaid by institutions to

commercial publishers. But what does this have to do with the ethical behavior of individual

TA journal editors? These editors are not paid “per acceptance” as are OA journal enterprises.

The TA journal editors have individual contracts, usually providing a straightforward annual

stipend. Their reputation, and that of their journal, are on the line if they start accepted droves of poor quality articles. They gain nothing.

Please explain further.

“These editors are not paid “per acceptance” as are OA journal enterprises.”

Where do you get the idea that OA journals pay editors “per acceptance” (or that OA journal editors are paid at all, or any differently than TA journal editors)? Not only is it patently not true as a general statement, it’s also not even a strong possibility that follows from the nature of the OA business model. (Should I assume that TA journal editors are paid “per subscription”?)

Please explain further.

In candor, your point is made. I don’t have statistical proof of any scenario you describe. My knowledge comes from my own 30 year’s experience in the commercial industry; bits & pieces of back-channel anecdotal chit-chat from other industry colleagues who are very careful about sharing company secrets; and inferences from studying (on the outside) how some (not all) questionable OA publishing houses operate. It makes sense that an OA publishing house would want to keep an editor who turns a profit for them, and will want to provide motivational compensation for that. There is nothing wrong with that either.

One would have to say that many of the claims made in this discussion forum are also rarely

based on scientific evidence. This is more an exchange of informal views and opinions,

that hopefully will spark more data-driven efforts.

The scenarios about TA publishing that I’ve been putting forth also make sense (to me, anyway), and I also have no hard proof of them. (I’m familiar with how these discussion forums work, thanks.) In the case of your particular claim, though, I’ve simply never heard of an OA editor getting paid per acceptance. It’s not impossible, and I even understand the incentives for this to be the case, but those incentives don’t seem extraordinarily greater, more obvious, or more common-sensical to me than the incentives I can imagine to pay a TA editor per subscription.

The resulting incentives would of course be distinct, though not necessarily opposite: the OA editor would have incentive to accept more (and thus, quite probably, to lower quality), while the TA editor would have incentive to accept more work of broader appeal (which, arguably to some, might also lower quality).

I hesitate to mention this but Beall describes some of these sorts of journals as publishers of last resort, in effect a vanity press. That seems to me to be a valuable service not a form of predation or fraud. Provided the author understands that this is happening of course.

Some of these publishers are actively seeking some “partnerships” with legit societies in order to encourage unknowing authors to submit papers. I know this because they contact me and other affiliated organizations trying to make a deal. A small engineering society was nearly sucked in.

A few have been caught claiming that they are members of certain organizations that lend legitimacy when they aren’t actually members. Further, some of these “publishers” host “conferences” and promise authors that selected papers will be sent to a real reputable journal. We end up getting an email with a zip file of 15 papers that they want us to consider. They did charge the authors for this “service.” Lastly, there are several scam organizations that promise to help authors get published and promise to help publishers get more papers–all for a fee. Their sites contain fake addresses, fake names, and little disclosure of fees. There is enough fraud to go around.

This discussion has kind of run its course but something just dawned on me. I think what John Bohannon did could be construed to be research as defined by the common rule. Obviously a hazy area but the definition by DHHS is “systematic investigation, including research development, testing, and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge”. I think it meets the definition. Obviously he is not working for an organization that is obligated to follow the common rule concerning the protection for human subjects in research but I believe many states have adapted the common rule Code of Federal Regulations (45 CFR 46) in whole or with some modifications as state law. This at least in my mind brings up the question of whether what he did was technically legal and more importantly whether it was ethical without appropriate human subjects review and I am pretty sure no IRB would approve his study as it was conducted.

Rightly or wrongly this wasted a lot of editors’ time and impacted significantly on the ones that didn’t waste too much time reviewing the manuscript :-). Seriously, if it is reasonable to consider Bohannon’s sham study research than what he did was a major violation of the ethics of human subject protections by any standard.

I don’t know the answer but would be interested in the comments of anyone with more background in research ethics.

I find this to be a truly bizarre formulation, making me wonder if it is offered seriously. The author is a reporter. He did what journalists do. It’s a good service. It is not scientific research.

Really? What he did seems to fit the definition of research as defined by the Common Rule. The rules governing human subjects protections in research are there to protect human subjects and I believe they have been adopted as laws in many states that apply to everyone in the state not just traditional researchers.

Investigating is one thing. Running a sting such as this is another. I am not sure it is correct to call this research or not but I don’t think it is an unreasonable question particularly when it was roundly criticized (fairly or unfairly) from a research perspective, not having a control group biased sampling etc. It seems like it was done very systematically with the goal of obtaining generalized knowledge, not just the behavior of the specific journals he sampled. I am pretty sure that meets the definition of research.

If Coca Cola puts together two different ad campaigns, and wants to find out which is more effective, and so runs those campaigns on local television stations and observes which results in higher resulting sales, should they also be held accountable for using human research subjects? If I want to figure out how popular hats are, and I walk down the street counting the numbers of people wearing hats, am I violating ethical principles?

I should have to point out, David, that these examples don’t involve wasting hours of the subjects’ time.

I might beg to differ as far as watching television commercials go.

Is that the criteria then that we should use for what’s ethical and unethical? Should anyone doing market research be required to seek approval from a licensing agency?

David, do you honestly not feel that misleading professionals into investing hours of effort into something is different from running adverts to an audience that expects to watch adverts?

I can at any rate tell you that I would be furious on my own behalf had I wasted time reviewing one of Bohannon’s submissions when these is so much else that I need to be doing.

You might not be very furious if yours was one of the journals that rejected the article and was called out by the journalist as one of the “good guys.”

I think studies of this kind always do raise ethical questions for the author. The same sorts of questions were raised back when Kent and Phil did something similar years ago (http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2009/06/10/nonsense-for-dollars/). Are you deliberately lying to an editor to do your experiment? Does this constitute fraud? I think the ultimate merit of the experimental results, and hopefully the reform that something like this inspires can outweigh the duplicitous nature of the process itself.

That said, suggesting this has anything to do with medical regulations regarding the use of human research subjects is a bit absurd.

This is a red herring, David. First of all, television commercials are, in fact, regulated: what kind of commercial can air, at what time of day and in conjunction with what type of program, is jointly decided by both public and private groups. Second, by choosing to watch television (or by allowing your children to watch television) you know that you are exposing yourself to commercials — so by turning on the TV, you offer your consent. Whether the intent on the part of the folks making the commercial is to sell you something or to see how effective it is at selling you something is a rather silly difference to be making in this context. Which are you saying is a bigger waste of the viewer’s time: the more effective commercial or the least effective one?

by choosing to watch television (or by allowing your children to watch television) you know that you are exposing yourself to commercials — so by turning on the TV, you offer your consent.

By that logic, an editor choosing to accept open submissions offers his/her consent to reviewing everything that comes in, regardless of its merit.

Which are you saying is a bigger waste of the viewer’s time: the more effective commercial or the least effective one?

Television in general?

That doesn’t follow at all, David. In volunteering my time as a peer-reviewer, I’m doing so as a service to my peers, to help them make better science — not to be a lab-rat in someone’s half-arsed experiment.

Journals set terms and conditions for accepting submissions. If you volunteer to review for a journal that has set those terms and conditions, are you not, at least under ebakovic’s logic, offering your consent in the way a television viewer does so by turning on the set?

“By that logic, an editor choosing to accept open submissions offers his/her consent to reviewing everything that comes in, regardless of its merit.”

But not regardless of its intent. The expectation that I have as an editor or a reviewer is that a submitted manuscript is intended to be a serious offering that the author believes is ready for review. As a television viewer, I don’t have any expectation about commercials beyond the rather banal one that the someone’s trying to sell me something — and “trying to find the best way to sell me something” is not sufficiently different than this to make me quibble.

“Journals set terms and conditions for accepting submissions. If you volunteer to review for a journal that has set those terms and conditions, are you not, at least under ebakovic’s logic, offering your consent in the way a television viewer does so by turning on the set?”

I think it would be a travesty if what we learn from this sting operation is that the terms and conditions for accepting submissions at journals all had to be explicitly supplemented with some statement that only serious offerings are acceptable. This is just a baseline assumption and there’s no reason to get all legalistic about it.

Keep in mind that nobody has said so far that what Bohannon did was somehow illegal; what we’ve been talking about here is whether the sting qualifies as human subjects research as that is understood in a standard research context.

Most journals do have just such a statement in their submission process–the author verifies that what they’re sending in is accurate and original.

But claiming that an editor whose journal practices open submissions has not consented to receiving bad papers (whether intentional or not) is absurd. Particularly if one uses your own logic–that merely by turning on a television, viewers have consented to accepting material they may find offensive or fraudulent.

Obviously not. When you submit a paper to journal, you the author make a set of statements, such as “this paper is not under consideration for publication elsewhere”. Bohannon systematically lied in making these statements. We was in no sense playing by the rules of the journals, and the editors and reviewers were in no sense spending their time on the activities they signed up for.

Such is life with an open submissions system. Sometimes authors will submit fraudulent papers as well, papers that are plagiarized or include falsified results. Some papers are simply flawed, though no active attempt has been made to decieve. As a peer reviewer, you cannot opt out of seeing these as well as the legitimate papers. You consent to reviewing what you were sent.

Your logic seems to be that because some authors sometimes submit bad papers, it’s OK for someone with an axe to grind to submit several hundred of them; and that because reviewers are resigned to sometimes seeing bad submissions, it’s OK to deliberately spam them.

If people accepted your perspective, I think we could confidently see a lot more people opting out of performing reviews.

Happily, I don’t think your perspective will be widely accepted at all. But perhaps other active researchers would like to chip in, and tell us whether they consider reviewing fake papers to be a legitimate use of their time?

Why are you implying that the author had an axe to grind? He is an investigative reporter. He grinds axes for a living. That’s what journalists do, and thank god for that. I suspect that you see the article to be an attempt to indict OA publishing. I do not. I see it as a way to expose some rascals. It would be great to expose all the rascals everywhere, but you have to start somewhere.

Chiming in to support Mike Taylor here: as a reviewer, I make a very sharp distinction between good-faith submissions (good or not) and bad-faith submissions.

Mike–no, that’s not my logic at all. As noted elsewhere, the ethics of any “sting” operation are always questionable. But if one accepts that by turning on a television, one consents to being lied to and presented with deliberately fraudulent material (as another commenter suggested) then a similar set of logic would seem to apply to having an open submissions policy and consenting to review a particular article. That’s part of being open to all comers, having to filter out the bad papers.

That says nothing of the ethics of deliberately submitting an incorrect paper, which I comment on here:

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2013/10/04/open-access-sting-reveals-deception-missed-opportunities/#comment-113259

Joseph, if you don’t see the Bohannon article as an attempt to discredit OA, then I can only assume you’ve not read the press release (or indeed the article). The agenda is as clear as day. Science has badly damaged its credibility.

I don’t see it as an attempt to discredit OA. If the author was trying to do that, he did not succeed. I see it as an expose of bad players. There are bad players everywhere. We don’t know if ther are more in the OA world than in the TA world. But I hope we can agree that exposing the bad players as this author has done is a public service.

“But if one accepts that by turning on a television, one consents to being lied to and presented with deliberately fraudulent material (as another commenter suggested)…”

Hey! This is a ridiculous misrepresentation of what I said. The example under discussion was this one from you:

“If Coca Cola puts together two different ad campaigns, and wants to find out which is more effective, and so runs those campaigns on local television stations and observes which results in higher resulting sales, should they also be held accountable for using human research subjects?”

This is very far from what any reasonable person would call “deliberately fraudulent”. Both ad campaigns are meant to sell the product. An example of a deliberately fraudulent ad would be one that says something like “Coca Cola cures cancer” — and I think we can both agree that this sort of thing should be (and in fact is!) strongly regulated out of existence. Many more moderate claims are attempted by advertisers, and companies are regularly sued for making false advertising claims. Let’s not pretend things are otherwise.

These papers were submitted not as scientific fraud but as publication fraud.

The construction of the papers was that they were all fake, but they were NOT exactly the same. They were made unique by swapping in different molecules, species and cancer cell targets. In that sense, this was no more (or less) “fraudulent” than someone publishing an incremental result in the midst of largely re-hashed data.

On the other hand, a journal with an open system expects that papers are submitted with the intention to be published. Whether or not they contain entirely fraudulent science is immaterial to this perspective.

I figure Bohannon abused the legitimate editors/reviewers – to the same degree, but in different kind – than someone who submits a false paper. However, he also exposed some (SOME) journals/editors/reviewers who were, themselves, falsely claiming to offer knowledgeable peer-review.

The papers did not contain valid science. They were written carefully so as to make this evident to a knowledgeable reader – as one would expect in a reviewer. Ideally, there would be 314 righteously outraged editors and something like 1200 (3 per paper) righteously outraged reviewers objecting to this abuse of their time.

“If I want to figure out how popular hats are, and I walk down the street counting the numbers of people wearing hats, am I violating ethical principles?”

No, of course not — if people are out in public, they have no reasonable expectation of privacy, and this is in fact one of the various types of situations that qualify for a waiver from informed consent.

Is a publicly accessible submissions system that receives and processes all papers submitted to be considered not “out in public”? What reasonable expectation does an editor have of only receiving accurate, high quality papers?

C’mon, David, gimme a break here. If you’re out in public wearing a hat you can’t expect that someone might not count the fact that you’re wearing a hat. But if you open up a journal to submissions, I think you have a reasonable expectation that the submissions you receive are legitimate. If your reply to this is that you simply don’t agree, then fine — let’s just stop this.

All right, last time round on this and then I’m out. No editor (and no reviewer) expects to receive only accurate, high quality papers. Every editors (and every reviewer) expects to receive only papers submitted in good faith. There is all the difference in the world between a bad paper and a troll. I find it very hard to believe you can’t see that difference.

Joseph Esposito: perhaps you could bother to do a search on the string helpfully quoted by David Solomon before coming to such a condescending conclusion about his comment. It would have led you to the definition of human subject research subject to regulation, and if you were interested enough to follow up on what kind of research qualifies for an exemption to regulation, you could scroll up to this section. Note in particular that the term “scientific” does not appear here, so using this term to exclude cases like Bohannon’s sting operation (arbitrarily, I might add) is spurious.

My reading of these regulations (with which I am quite familiar as a member of a university IRB committee) is that Bohannon’s sting operation technically qualifies as human subjects research that is subject to regulation. Of course, a sting can’t work if you are required to ask for informed consent from your human subjects, even if you are granted permission to conceal crucial elements of the study from those subjects — so, the case would have to be made for a waiver of informed consent, as described in subsections (c) and (d) of the requirements for informed consent.

Now, your point appears to be that journalism involving human subjects research isn’t (and shouldn’t be) subject to these regulations, while research that is for all intents and purposes the same kind of thing but performed by “(scientific) researchers” is and should be. To paraphrase you: I find this to be a truly bizarre distinction, making me wonder if it is offered seriously. The fact that this research was published in Science and that the vast majority of people will only know about it via superficial press releases and secondary reporting means that its results are bound to be considered “scientific” and generalizable in exactly the direction that this superficial coverage (and prior perception by many) has been biased toward: that open access publications, by their very definition, fail to conduct appropriate peer review.

You also state that Bohannon “did what journalists do.” Do you really believe this? The reason it’s called a “sting operation” is precisely because it goes beyond what journalists typically do, which is to obtain, synthesize, and report on information that is either in the public record or obtained via sources that are made aware in advance that their comments will be on the record (and those sources are given the option to remain anonymous).

Looking through your linked regulations:

(e) Research subject to regulation, and similar terms are intended to encompass those research activities for which a federal department or agency has specific responsibility for regulating as a research activity, (for example, Investigational New Drug requirements administered by the Food and Drug Administration). It does not include research activities which are incidentally regulated by a federal department or agency solely as part of the department’s or agency’s broader responsibility to regulate certain types of activities whether research or non-research in nature (for example, Wage and Hour requirements administered by the Department of Labor).

Which federal agency has specific responsibility for regulating the research being done here?

I cannot tell if you are joking or not. I sincerely hope that you are.

Joseph Esposito: Is this a reply? I’m not at all joking.

Just to be absolutely clear: I have been following up on David Solomon’s comment, which asserts (albeit tentatively) that Bohannon’s sting operation “could be construed to be research as defined by the common rule”. I’ve been defending that assertion further, but neither of us has so far claimed that — even if the assertion is true — Bohannon did something illegal or unethical. (And to be even more clear David Solomon raises the question, but does not claim it.)

This makes David Crotty’s reply to me just above particularly off point. I believe that we are all operating under the correct assumption that there is no agency (federal or otherwise) that has responsibility for regulation of this kind of sting operation. The question is whether there should be, and if not, why not?

As I mentioned before, I speak as a member of a university IRB committee, specifically looking at research in the social and behavioral sciences. Many of the proposals we look at are not federally funded and the vast majority of them are very low risk sorts of studies, and yet the university still insists (rightly, in my view) that anything falling under the common rule definition of research should be regulated in this way.

It cannot and should not be regulated in this way because the author is out of your jurisdiction. I repeat: he is a journalist and is not (to my knowledge) on the faculty of a research institution. I am thinking with considerable anxiety about what it would mean for IRBs to extend their purview beyond the academy.

And I didn’t suggest this! Federal agencies have regulatory bodies like these, and then this was adopted by universities (in many cases because they have federally-funded research to regulate, but in some cases voluntarily). My suggestion here is that perhaps journalist should self-regulate in the same way that we at universities do.

I would suggest that putting investigative journalism under the supervision of either a government or the very bodies that the journalist is investigating seems self-defeating, and against the nature of a free and open society.

To extend your logic, perhaps any interaction with any other human being should be regulated. If I meet someone in a bar and ask them out, is that an experiment involving a human subject (hypothesis: this person thinks I’m attractive)? Should that be regulated. I may after all, be wasting that person’s time. This line of thinking is getting increasingly surreal, I think I may be done with this conversation.

The surrealness of this is coming entirely from you both (David and Joseph), and probably has a lot to do with the fact that you don’t have any experience with the kind of regulation we’re talking about here (and the fact that you appear not to want to be further informed).

“This person thinks I’m attractive” is not a generalizable hypothesis, nor one that you plan to publish somewhere. Don’t throw out straw men. But just to further inform you: research that involves situations in which people are not being subjected to anything “out of the ordinary” (where being asked out in a bar would be an example of something ordinary) are frequently, and correctly, exempted from human subjects regulation.

Journalists and cops get to do all kinds of things that Psychologists can’t. They have a different set of professional standards. It’s not like lying to people is illegal.

Here’s a prior write-up of these issues, if of interest…

Bill

http://www.annemergmed.com/article/S0196-0644(13)00547-7/fulltext

And here is another write-up of these issues, rebutting assertions that fee-based OA journals incentivize acceptance and that TA journals do not.

http://legacy.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/newsletter/10-02-06.htm#quality

Now we have real and proven data and result of the quality of SOME OA journals (neglecting the fact that it was not compared with similar subscription based journals and other weakness of this study). Even though this experiment is ‘not perfect’, but I am so happy to see that it throwing light on the quality of ‘screening and peer review service’ of OA journals. I strongly believe that the scholarly publishers should work like ‘strict gate keeper’ by arranging honest and sincere peer review service. This is the main difference between a ‘scholarly publisher’ and a ‘generic publisher’ (who publishes anything). Other works like typesetting, proofing, printing, web hosting, marketing, etc are important but not unique for a scholarly publisher. (My personal opinion is that we should not waste time by debating–Good OA, –bad OA–good CA–bad CA, etc. It is the time to work. We must jump to more effectively analyses and use these huge precious data)

I know and strongly believe that Beall, being an academician-librarian, also gives the highest importance to this particular criteria than any other thing. I congratulate Beall that his theory has been experimentally proven by the Sting Operation of Science.

I know this sting operation is going to generate a huge debate and one group will try to find out the positive points and other group will try to prove it as bogus experiment. A simple endless and useless fight and wastage of time. It will be more important to find out some way to use this huge data more effectively.

Now I have some suggestions and questions

1. How are we going to use these huge data generated by this year long experiment?

2. I request DOAJ, OASPA to do some constructive works by using this huge data.

3. Can we develop some useful criteria of screening OA publishers from the learning of this experiment?

4. Is there any way of rewarding the publishers, who properly and effectively passed this experiment (rejecting the article by proper peer review. I noticed some journals rejected due to ‘scope-mismatch’. It is definitely a criterion of rejection. But it does not answer, if scope was matched, what would happen).

5. I saw the criticism of Beall that ‘he is ..trigger-happy’. It is now time for Beall to prove that he not only knows to punish the bad OA, but he knows to reward also somebody, if it intends to improve from the previous situation. Is there any possibility that this data can be used for the ‘appeal’ section of Beall’s famous blog. Sometimes judge can free somebody depending on the circumstantial proof, even if he/she does not formally appeal. (Think about posthumous award/ judgment.) I always believe that ‘reward and inspiration of good’ is more powerful than ‘punishment for doing bad’. But I also believe that both should exist.

If anybody tells that “The results show that Beall is good at spotting publishers with poor quality control.” Then it tells one part of the story. It is only highlighting who failed in this experiment. It is not telling or highlighting about those publishers who passed this experiment but still occupy the seat in Beall’s famous list. I really hate this trend. My cultural belief and traditional learning tells me that “if we see only one lamp in the ocean of darkness, then we must highlight it, as it is the only hope. We must protect and showcase that lamp to defeat the darkness”. I don’t know whether my traditional belief is wrong or right, but will protect this faith till my death.

I really want to see that Beall officially publishes a white-list of ‘transformed predatory OA publishers’, where he will clearly write the reasons of its removal from the ‘bad list’. So, that from that discussion other lower quality predatory OA publishers will learn how to improve (if they really want to do so) and will learn how to get out of Beall’s ‘bad list’. This will step will essentially complete the circle, Beall started.

Ideally I STRONGLY BELIEVE that Beall will be the happiest person on earth if in one fine morning Beall’s list of ‘bad OA publishers’ contains ‘zero name’, by transferring them to Beall’s list of “Good OA publishers” by transforming them with the help of review process initiated by Beall.

Akbar Khan,

India

Although it’s not prominently displayed on Beall’s website, his criteria for inclusion in the list is much more developed that Phil Davis portrays it to be. It can be found at the following link:

Also, I would caution Davis against the juvenile tone taken to characterize Beall as “the sheriff of a Wild West town throwing a cowboy into jail just ‘cuz he’s a little funny lookin.” I can’t help but feel that Davis decided to not spend a whole lot of time looking at the websites of some of the publishers that appear on Beall’s List. For instance, take a look at the website of the publisher called Asian Academic Research Associates. They have a journal called, and I quote, “The Asian Academic Research Journal of Multidisciplinary”. That’s it! Multidisciplinary what? I don’t see the need for any control group with that kind of “circumstantial” evidence.

Many of the publishers that Beall chooses for inclusion on the ‘list” are not champions of the OA scholarly publication model. They are criminals fishing for suckers. They are exploiting for private profit a model that was designed to increase the accessibility of scholarly literature. In the process of this exploitation, as Bohannon’s article points out, the scholarly literature and the OA model are the greatest victims.

For me it is more important to find our few sources of light in the ocean of darkness. People are more busy to find out the weakness of the study, how these study should have been conducted, etc. Some peoples are considering this as a ‘designer study to produce some designed baby’, etc. And I AGREE to all of them. Yes all them are true. But in this huge quarrel and cacophony are we not neglecting some orphan babies born from this study (yes they born accidentally and not designed or expected to be born: as most of the large inventions are accidentally happened)?

I have made some childish analysis with the raw-data of the report of John Bohannon.

Bohannon used very few words for praising or highlighting the journals/publishers who successfully passed the test. He only mentioned about PlOS One and Hindawi, who are already accepted by academicians for their high reputation. At least I expected that Bohannon will include a table to highlight the journals/publishers, who passed test. I spent very little time to analyze the data. Surprisingly I found some errors made by Bohannon to rightly indicate the category of publishers (DOAJ / Beall). I have indicated some errors and I could not complete the cross-checking of all 304 publishers/journal. Bohannon used DOAJ/Beall as his main category of selecting the journals. But error in properly showing this category-data, may indicate that he spent more time in collecting the raw data, than analyzing the data or curating the data.

I found more members of Beall’s list is present in Bohannon’s study. But Bohannon did not reported this fact.

Table 1: List of 20 journals/publishers, who Rejected the paper after substantial review (May be considered white-listed journal/publisher)