From a news perspective, the recent report by Google researchers that more highly-cited papers are found in non-elite journals is about much more than the distribution of citations.

The idea that digital publishing may be helping to raise the awareness of specialized and geographically-isolated journals–along with the authors who publish in them–has a sense of fairness and egalitarianism built into the storyline. The notion of a weakening elite cadre of journals also awakens our political disdain for publishing plutocracies and the scientific bias that may result from it. There is some part of us that wishes science to become more democratic.

When a paper like this comes to light, there is a always a temptation to begin debating its broader context before we can vet its methods. Like the paper claiming that scientists are reading fewer papers, journalists rarely put much effort into validating even the most basic numbers underlying the authors’ bold claims. It is much more newsworthy to discuss the paper’s significance.

Instead of ruminating about the broader economic, sociological and technological changes that may underly Google’s findings, I’m going to focus on on their methods because I believe that their findings may simply be an artifact of the researchers’ strict definition of what constitutes an “elite” journal.

The Google team defined an “elite” journal as one of the top 10 most-cited journals (based on their h-5 index) for each of their 261 subject categories and for each year between 1995 and 2013. Google researchers then identified the 1000 most-cited articles in each category-year and looked to see how many were published in the elite versus non-elite journals.

Google’s method is simple and intuitive, but it contains two fundamental assumptions that they don’t bother to verify in their paper.

First, the use of a top-ten list assumes that the production of scientific literature is constant from year to year. It isn’t. If we assume that the number of articles grows approximately 3% per annum, and we want to conserve the ratio between elite and non-elite journals, then by 2013, there should be 17 journals in their “elite” group not 10.

Second, the Google researchers also assume that elite journals publish roughly the same number of articles each year, which also doesn’t seem to be valid, at least for medicine.

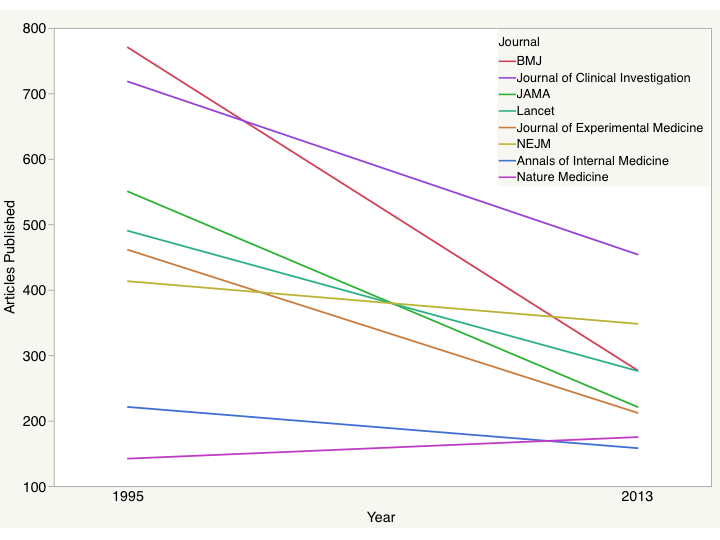

Below is a plot of what most of us would consider “elite” medical journals. With the exception of Nature Medicine, this group of titles shrank by an average of 78% articles between 1995 and 2013. Two journals (JAMA and BMJ) currently publish less than half the number of articles than in 1995. Taken together, these eight elite journals eliminated 1644 possible publication slots.

If we think of this model as a game of musical chairs–where the chairs are publication slots in elite journals and the children circling them are prospective articles–there are more children playing this game each year and fewer chairs to fill when the music stops.

I’ll admit that the analogy of musical chairs to describe the process of slotting articles into journals isn’t entirely correct. In musical chairs, luck has a lot to do with whether you’ll be close to an open chair when the music stops–that, and some shear forcefulness. Publication in an elite journal, however, is not entirely a game of chance. Editors are skilled at spotting the best articles and have a pretty good idea of whether an article will be cited, but they are not perfect. Editors are people and people are subjective. Good articles will slip through their selection process and get published elsewhere. Authors, alternatively, may give up on the elite journals if they know their manuscript will be stuck in the review and revision process for some time. Everyone is trying to make the best decision with never enough information. But when the number of available publication slots in elite journals shrinks each year, the odds are simply stacked against authors.

In sum, an expanding annual production of scientific articles coupled with a limited (or shrinking) number of publication opportunities in the elite journals will invariably lead to more highly-cited papers being found in non-elite journals. If the Google researchers wish to make claims about the distribution of articles published in elite versus non-elite journals, then they needed to account for the annual growth of the literature as well as the changing nature of elite journals.

Discussion

25 Thoughts on "Growing Impact of Non-Elite Journals"

Nice analysis. The Google paper also describes a “top-1000” papers concept, which seems to suffer from the same problem — it doesn’t reflect the increases in article production. The top 1000 articles in 1995 would have been a larger proportion of total output in any field than the top 1000 articles would have been in 2013. So, you’d expect fewer citations to a relatively smaller proportion of papers.

The notion of compound interest seems to matter because of these failures to adjust. If the literature grew at a 3% rate, compounding that over 18 years would lead to an increase of about 70% in total. This comports with what Google found. By not adjusting the lists of elite journals by 70% as well, there you have it, to restate your point.

The Google report also implies that discoverability (aka, Google) is a major contributor to the findings they claim. It’s true that adding citations to articles may be a main result of increased discoverability, but this is a mixed bag when it comes to quality.

Another possible analysis of these data would be to look at the growth in citations to obscure journals, which may be a sign of citation padding. Many authors bulk up their papers with more references than necessary. Has Google made it easier to toss a handful of obscure references in at the last minute? Has increased discoverability led to more reference padding? Google might not be as motivated to look into that, for obvious reasons.

Google could have picked a “bottom 10” set of journals and flipped the analysis to see if more references are being dredged from the lowest tier. That would have been a very interesting analysis — it would have the same problems and limitations as this study, but would not be a good PR message for a major search provider.

Thanks Kent. Inflation of the literature alone could explain their results; so could a shrinking number of publication spots in the top-10. Taken together, we would expect even a larger effect. There are a number of technological, sociological and political theories that may explain an attenuation of citations. And there are others (such as increased pressures to publish in top journals) that would explain the opposite effect. However, I don’t think anyone should be making strong conclusions about the concentration of citations without first adjusting for basic trends in the literature.

This is indeed a fine analysis, and as often happens it raises some interesting questions as well. In this case, why are all these journals shrinking? One of the leading explanations for the journal price increases over this period is that journals are publishing more articles, but this sample shows the opposite very strongly. Is this sample an outlier as far as journals in general are concerned or is the price explanation incorrect?

While the average scientific journal may be expanding, it doesn’t rule out a shrinking elite class. Top journals maintain their elite status by being highly selective, accepting and publishing only their best submissions and rejecting the rest. Getting smaller is an indication of growing competition among elite journals. There is a downside to this approach, however. Extremely high rejection rates can turn off authors and turn some journals into a type of ‘old boys club.’ And if we take the elite shrinkage to an extreme, we are left with a cadre of top journals, each publishing exactly one review article each.

Indeed, this would make the elite sample an outlier, as I suggested. This then raises the question whether it is representative of the other 260 disciplines analyzed? It also raises interesting questions about the dynamics of the publishing ecosystem, namely why is this shrinkage happening? A local explanation may be that medicine is unusual. For example my understanding is that medical journals have atypically high revenues from reprints and advertising. Changes in these revenue streams might drive shrinkage. There is clearly a lot we do not know here.

A common trend over the last decade has been the spinning off of new journals from established ones. See the Nature or Cell families of journals for examples. Often when you have a really strong, established journal, it makes sense to start a sister journal, which allows you to capture an even larger section of the top articles while still continuing to increase the rigor and standards of the top level journal, likely reducing it in size.

There are many reasons why some journals are more selective than ever, from what I can see. First, they have achieved a level of prominence where there is little risk to being more selective. In fact, there is risk in not ratcheting up selectivity. Second, being more selective actually makes them more competitive — better impact factor, better articles on average, and that makes them more likely to get first shot at the best articles coming out of the major research centers. Getting the first shot at a paper is a big, big deal for these journals. Third, these journals tend to do a ton of review and editing compared to most other journals, making each article they accept more expensive, burdensome, and complicated to publish. They have high and increasing editorial costs and workloads. With revenues harder to come by, there is a natural tendency to reject more and work harder on fewer articles. Fourth, a few of these journals have made strategic shifts away from research articles in order to become more readable, which puts more emphasis on news, opinion, reviews, and other items. Finally, some of these journals are part of journal systems that can absorb rejects relatively easily, so there is less downside for authors rejected while the family of journals can publish papers the flagship attracted. This accounts for some papers shifting away from the flagship.

I’m confused by this analysis. The paper looks at a fixed pot: the 1000 most-cited articles in a field, and finds that an increasing number of them are published in non-elite journals.

I don’t see how growth in the scientific literature has any bearing on this. The top 10 journals in each field publish far more than 1000 articles between them, so have ample slots to produce the top 1000 most-cited articles in a field in any given year. It doesn’t matter whether the scholarly literature is expanding – we are talking about the fixed, fairly small, pot of top-cited articles, and where they appear. [Even in 2013, the majority of them still appear in one of their field’s top 10 journals – it’s just that this extreme is less marked than in 1995].

The top journals shrinking in size might be significant, I agree. But I’m not sure that the ‘expansion of the scientific literature’ comes into play here.

Thanks for your comment, Richard. These top-1000 cited articles could indeed fit in the top-10 cited journals. However, this publication model assumes three things: 1) that authors are submitting all of these top-1000 articles to the top-10 journals; 2) that editors can properly identify each of them and accept them for publication; and 3) that everyone has perfect information about the future citation potential of an manuscript upon submission. If we assume that there is some degree of uncertainty in the system (that authors or editors do not have perfect knowledge of the future citation potential of any article), then we introduce some stochastic (random) component to the publication model. Start removing publication slots in the top-10 journals and the odds of slotting one of those top-cited articles into one of the top-cited journals start to decline. Increase the number of articles each year and the odds also begin to decline. Both processes lead to fewer top-1000 articles making their way into top-10 journals.

Put simply, when you do an experiment, the goal is to keep all variables equal, except for the variable being measured. So you need to control for a changing population. If in my first experiment I report on the number of dead cells in my culture, and then repeat the experiment using a culture volume twice as large with twice as many cells, the conditions have changed and the numbers are not directly comparable.

If in 1995, the top 1,000 articles represents the top 5% of the literature, and in 2013 the top 1,000 articles represents only the top 1% of the literature, that makes for a problematic comparison.

Similarly, if there were 100 journals in 1995, the the top 10 shows you the top 10%. If in 2013 there are 1000 journals, the top 10 now limits your view to the top 1%.

To effectively compare, you must either shift the raw number totals to keep things relatively equivalent, or deal in percentages and ratios, rather than raw number counts (1,000 articles and 10 journals versus the top X% of articles and the top Y% of journals).

The shrinking of the journals matters as well–if the top 10 journals in 1995 published 1000 articles and they had an 85% success rate in picking the top articles, you’d see 150 or so top articles in non-elite journals. But when the journals shrink and only publish 500 articles, if they still have that 85% success rate (or even if they’ve increased it to 100%), you’re going to see more of the top 1000 in the non-elite journals (at least 500 articles given the space constraints).

Thanks, I see both your points. It’s plain to see why the shrinking of the top 10 journals’ capacity matters, but the effect of the expanding literature is a little more subtle. If 1000 top articles represented 5% of the literature in 1995 but only 1% in 2013, one might expect, all other things being equal, to see these 1000 articles concentrated even more highly into the top journals. But I see that it has some kind of effect.

Lariviere et al (http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1304/1304.6460.pdf) last year looked at the same question, and examined the top 1% or 5% of papers. They found that the top journals had a reduced share of this top x%, but in this case, it was clear that this was because the top journals were getting a smaller piece of the expanding literature pie. I expect this is why Google Scholar wanted to look at the top 1000 papers only, instead, to examine something more complex than the Lariviere paper attempted. But, as you say, this doesn’t manage to strip away the complications.

I consider the concept of “elite” applied to scientific journals naive, a misunderstanding of the nature of science. The origin of the study – Google – only reinforces my impression. Many of Google’s top 10 carry ads. So, it’s all about advertising – not science.

The number of science journal articles has doubled every 15 years since the 17th century. Science “twigs,” with new specialties also doubling and redoubling. Each “twig” has its own “elite,” with its own focus, led by outstanding researchers, editors, and organizations. Authors often prefer to reach their peers with their esoteric work rather than to reach beyond, where most readers have little interest.

Phil as always interesting. As a lay person, I have to ask: As journals become more and more specific and concomitantly research too, are your findings surprising?

Great analysis and post Phil. I’m torn between attempting to add some humor to the discussion with a “Seinfeld” reference, but I think “Annie Hall” is more relevant. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5U1-OmAICpU

A few comments:

We thought about the idea of using percentiles to determine the top-cited journals and articles. There are two reasons for using fixed numbers of top-cited journals and articles. First, this fits most publishing authors’ notion of elite journals and articles. If you ask ten colleagues across the campus about the “top” journals in their field, you will usually get a small number, When hiring committees or letter of reference writers mention “top” journals, again, they usually have the same small set in mind. It is this shared perception of a small number of “top” journals that causes authors to seek out the elite journals in their field.

Second, the publishing pattern also fits the small fixed number model. It is impressive that so many fields have such a large fraction of their top-1000 most-cited articles in the 10 most-cited journals. The gravitational pull (ie the prestige factor) of the journals known by everyone as “top journals” is very strong even though the effect of wider physical distribution of these journals has largely gone away with the shift to online publication.

Phil mentions the idea that the changes described in the paper could be the result of a stochastic editorial process working on a continually increasing number of article submissions. If this were indeed the case, we should expect the magnitude of change in each broad area to be roughly proportional to the growth in the number of articles in the area. Looking at Table 1 of the paper, Physics & Mathematics sees an increase of 204% in the number of top-1000 articles in non-elite journals whereas Life Sciences & Earth Sciences sees an increase of 18%. If the changes were due to a process proportional to the number of articles, this would require that the growth for Physics & Math to be 10 *times* the growth for Life Sciences & Earth Sciences. As it happens, and as one would expect, the growth in the two areas is roughly comparable; in fact, Life Sciences & Earth Sciences sees a larger growth.

I guess my questions come into the comparisons between very different eras. If the assumptions are essentially correct for 1995, then are the identical conditions accurate for 2013? So much has changed in the world of science over that time, enormous growth in the number of people doing science, globalization, tremendous increases in the numbers of papers and journals being published. Is it realistic to assume that what held in 1995 still exactly holds in 2013?

One thought might be to look at what is defined as an “elite” journal. Rather than the somewhat circular reasoning of just taking the top 10 journals and declaring them to be elite, why not look at a series of metrics shared by those journals in 1995. Then look each year to see whether the number of journals on that level has changed and adjust the definition accordingly over time?

Rather than looking from the author’s side, i.e. what journals authors submit their papers to, another approach is to look from the reader’s side: i.e. what journals are readers reading (and citing). Considering that digitalization and the creation of new databases (e.g. Google Scholar) make it easier, or more likely, to find interesting/relevant papers in “non-elite” journals, it is expected that more citations will go towards those papers (even if the elite papers continue being read and cited). Hasn’t the number of reference per paper increased substantially in the last 20 years?

This “report” does not appear to have been published in any journal, nor does it acknowledge any peer reviewers. Your quick review has found several serious deficiencies that should have been caught. All of this indicates science with a very questionable pedigree. Yet a whole bunch of comments are taking it seriously. Are the cooks not following their own recipes?

We cover many analyses and reports that are not published in peer reviewed journals. Oft times an argument is made in a newspaper article, a blog or by a company. If we were to limit our discussion strictly to the peer reviewed literature, we would miss a great deal of information. Publishing is, at its core, a business, not a field of scientific research, hence different types of information sources may be relevant.

And to be fair, the scholarly research world is seeing an increasing use of preprint servers for review and commentary on papers before they are submitted for formal publication.

One wonders if mixing research articles with review articles skews the results?

This is an absolutely important point. Let me give an example. One could submit, in the horticultural sciences, to the crème-de-la-crème of journals in this field, Scientia Horticulturae, published by Elsevier. Associated with that paper would be the fame and the notion among peers that an achievement was made in an “elite” journal. Of course, only those with access to the expensive Elsevier access would be able to use that paper, and that chance is decreasing as readership moves away from such expensive elite options. Notwithstanding this reality, Elsevier still boats the highest number of scientific papers in the world, at about 12.5 million. So, the driving force is still powerful… for now. But, let’s look towards another two alternative journals, now published by DeGruyter, Folia Horticulturae or Journal of Horticultural Research. A more realistic, yet strict, peer review, a timely, responsible and responsive team of editors (vs the arrogance often displayed by the formerly listed elite journal), will lead to a boost in the number of papers published there, even good papers, as more and more scientists see the real benefit of having a FREE open access paper in a non-elite journal as opposed to one in an elite journal that is only trying to scam ur money, namely about 2500 US$ for a single open access PDF file (Elsevier costs). Those who can freely abuse of money that is not from their own pocket or grant, such as those who receive university or library funding for publishing in OA could move to a different class of “elite”, namely Nature Publishing Group’s Horticulture Research. With already 27 papers published since inception and an article processing fee of 2650 GB pounds, it is not hard to see where the emphasis lies in this Sino-US publishing collaboration. Previously, it was dangerous to lay one’s eggs in different nests. Now the complete opposite is true: it is absolutely unwise to lay all one’s eggs within a single nest, even though some nests carry more risks than others. Ultimately, it is the rich scientist who has ample funding who has more choice, provided that the research is good, although fortunately for the lower strata of middle-class scientists (economically and scientifically), the increase in OA journal choices brings choice, and relief from the control of the traditional STM publishers.

Personally, I have decided not to cite papers from ‘elitist’ journal anymore, as possible as I can, to avoid participating in the amplification of their ‘ego’.

Science, knowledge and elitism are not compatible.