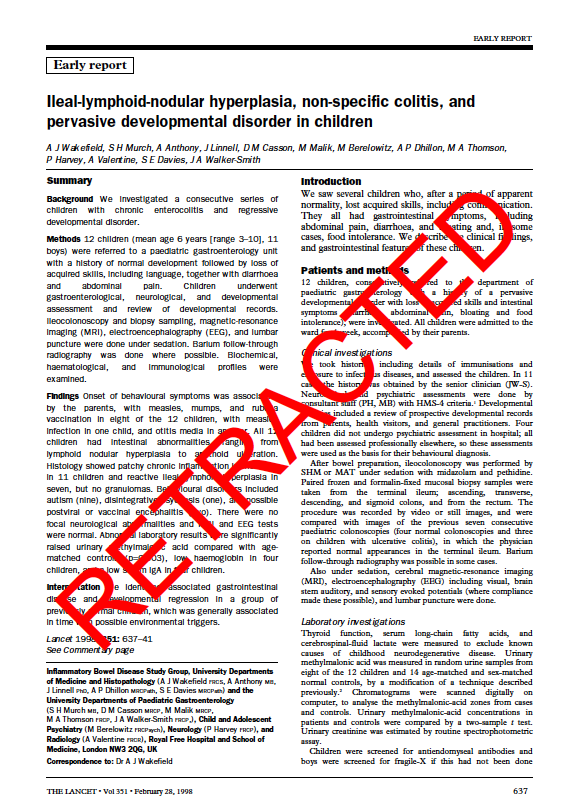

Search Google for the phrase “ileal-lymphoidnodular hyperplasia,” and you are likely to find several free copies of a popular medical article hosted on public websites around the Internet. The problem is, this article was retracted in February 2010, the result of a investigation that ultimately found the paper fraudulent and stripped its author of the right to practice medicine.

Search Google for the phrase “ileal-lymphoidnodular hyperplasia,” and you are likely to find several free copies of a popular medical article hosted on public websites around the Internet. The problem is, this article was retracted in February 2010, the result of a investigation that ultimately found the paper fraudulent and stripped its author of the right to practice medicine.

If the medical terminology of this paper is still confusing you, this is the discredited study by Andrew Wakefield, who in 1998 published a paper which linked early-childhood vaccination with autism and began a decade of mass hysteria about the safety of immunization.

If you make it to the journal’s website, you will find the words “RETRACTED” printed boldly on the article; however, many readers will never get this far. There are many free copies of the earlier (unretracted) version sitting on public websites. For all intents and purposes, the article is still published.

The vaccine-autism scandal received international press coverage. Yet every year, thousands of articles are either retracted or corrected with little (if any) media attention, and there is little a publisher can do to alert readers if they don’t visit the journal’s website for a new copy.

In her article, “Distinguishing published scholarly content with CrossMark“ (Learned Publishing, April, 2010), Carol Anne Meyer, Manager of Business Development and Marketing for CrossRef, writes:

It stands to reason that if a publisher goes to the trouble of issuing a change notice for an article, a mechanism should exist to easily alert readers to those changes.

The issue of persistent, uncorrected errors in the scientific literature is not new. Errors promulgated easily in print journals because readers rarely became aware of editorial notices appearing in later journal issues. Electronic publishing made it much easier to update articles, but for those who routinely download PDF copies to archive on personal computers, getting updates to readers is much more difficult. Starting 1987, the National Library of Medicine began indexing retractions and correction when notified by the publisher.

Article repositories only add to the problem of versioning. While they are designed to archive and disseminate copies of research papers, few have any mechanism to correct errors, update the status of articles, or alert potential readers if the article becomes retracted. The problem is even worse for papers stored on personal websites.

For example, the 20o2 article, “Rule learning by cotton-top tamarins” was subsequently retracted by the journal Cognition; however, the in-press copy is still available from the Harvard lab’s website and shows up 1st in Google while the publisher’s website is listed 5th.

In spite of publisher guidelines on how to alert readers of retractions, the problem of versioning wasn’t being solved on its own. A new approach was needed to provide readers with authoritative source on the status of articles, and not only for high-profile retractions, but for the thousands of corrections and updates that are issued by publishers each year.

This is the rationale for CrossMark, a new service by CrossRef which will debut later this year.

According to Meyer, articles baring the CrossMark logo will be linked to metadata on the status of the article. Clicking on the logo will retrieve that information. Most often, readers will see a message that the document is current, although occasionally they will alerted that the document has been updated, corrected, or retracted. In these cases, a CrossRef DOI link will point readers to the publisher’s website for the most current version.

CrossMark is not limited to journal articles, but can be used for any kind of document that has been issued a DOI, like books, book chapters, and conference proceedings. According to Meyer, CrossMark is secular when it comes to publishing model; a publisher, however, must commit to maintaining the content with any updates. She writes:

At CrossRef, where persistence is part of the mission statement, we believe that the act of publishing a document implies a commitment to maintaining stewardship of it for the long term. Whether a publisher chooses to adopt the NISO definition of a version of record or not, it commits to communicating changes, errata, revisions, or, in the worst case, retractions. Prepublished versions of scholarly content may be convenient and free, but they do not come with the level of commitment that publication entails.

CrossMark is the brainchild of Geoff Bilder, Director of Strategic Initiatives as CrossRef. Many know Bilder for his intensity, although he is not above a little good-natured ribbing from the Scholarly Kitchen (see CrossDress). The idea for CrossMark came to him several years ago when visiting a publisher and saw a retraction notice for a medical reference work tacked to the bulletin board in their lobby. “How could it be that after almost a decade of electronic scholarly publishing, we still had no standard, automated way to alert people to changes in the status of published scholarly documents?” he responds by interview.

Over the past several years, pressure from funders, universities, and governments have increased the number of article versions being placed in public archives, mostly in the form of author manuscripts. Little is known on the status of many of these documents and how many were subsequently retracted, corrected, or updated.

We have a solution. Now it’s important to document the extent of the problem.

Discussion

13 Thoughts on "When Bad Science Persists on the Internet"

One would think that asessing the extent of the problem comes before establishing such an elaborate tracking system. The Internet was designed to be highly distributed. We may just have to accept the downside of that design. Important retractions have their own way of spreading.

Very good article. Although it is correct to say (as David does) that the Internet is a highly distributed system, this problem is a longstanding one that the internet (publishers hoped!) would solve, as it freed us from only being able to publish corrections (including retractions) in print.

As things stand a publisher will do what it can, eg sending correction feeds to all the A&I (abstracting and indexing) services where its journal content is listed. This means, for example, that someone acccessing an abstract on PubMed or Medline will see the correction/retraction notice. Also, obviously, the publisher marks the retraction on its own copy of the paper – which the publisher should publicly say is the definitive version, as far as it is concerned. However, as you write, there is not much a publisher can do about the many personal archived copies out there, or indeed any other copies on various websites, etc. Quite a challenge. I hope crossmark does something to alleviate the situation (as retractions, though important, are but one aspect of the post-publication correction – papers often need to be corrected without needing retraction).

At least PNAS early on implemented a process to bundle the retractions/corrections to the original article pdf’s, other publishers haven’t followed that lead. Hopefully someday GoogleScholar will implement an option to search only content with the CrossMark logo.

Observation: scholarly literature is scaling.

Problem: filter>publish peer review by scholarly publishers is not scaling.

Answer: publish>filter peer review by readership.

To expand on Maxine’s observation that “retractions, though important, are but one aspect of the post-publication correction”- CrossMark is not just about flagging retractions or even corrections, it is about persistently tying together any kind of significant update to published content. Some publishers are actively thinking about how the mechanism can be used to more accurately record the dynamic nature of scholarly communication. For example BioMed Central has just (serendipitously- I swear this wasn’t planned) posted an update on some experiments that we are conducting with them to use CrossMark as the basis for “threaded publications”. http://bit.ly/hFkacR

Intensely, –G

I am afraid this sounds like yet another linking vision that only works if a lot of people do a lot of work for nothing. Phil mentions author manuscripts and in-press versions. Is every author supposed to adopt this linking mechanism?

As someone who studies the dynamic nature of scholarly communication, I can see the vision, but I think it underestmates the complexity of the system and the cost of recording it.

Stay tuned for the April issue of Against the Grain that contains a special section co-edited by NISO’s Todd Carpenter and me titled “The Challenges of Bibliographic Control and Scholarly Integrity in an Online World of Multiple Versions of Articles,” including another article by Meyer on CrossMark.

Those interested in following the scope of the problem of retractions in particular may be interested in this study coauthored by Liz Wager of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). The paper, published in the Journal of Medical Ethics, investigates retractions in PubMed from 1998 to 2008. The authors conclude that retractions in the medical literature have increased tenfold from the early 1980s to the period 2005-2009. They also cover the reasons for the retractions in detail. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1136/jme.2010.040964

Coincidentally, the latest issue of the Journal of the Medical Library Association has an article on this theme: “Reporting of article retractions in bibliographic databases and online journals.” http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3066576/

A key attribute of journal publishing is that “incorrect” articles are “corrected” by subsequent publication of “correct” articles, and so on. It’s the process that polices quality not the publishing entity itself. IMHO CrossMark is a sledgehammer to crack a nut with respect to retractions, but as a method for branding process it is a powerful idea…

Unfortunately, this self-correcting aspect of the process does not always work well. See “Fawlty Towers of Knowledge”: http://interfaces.journal.informs.org/cgi/content/abstract/38/2/125