Earlier this week, I mentioned something that’s been troubling me ever since I came across it a couple of months ago — the fact that BioMed Central (BMC) has a program through which pharmaceutical companies and, more surprisingly, a tobacco company have been able to subsidize publication fees for their scientists into BMC open access (OA) journals.

Earlier this week, I mentioned something that’s been troubling me ever since I came across it a couple of months ago — the fact that BioMed Central (BMC) has a program through which pharmaceutical companies and, more surprisingly, a tobacco company have been able to subsidize publication fees for their scientists into BMC open access (OA) journals.

Corporations and scientific publishers have had an uneasy relationship, and for good reason — the record is littered with spectacular disasters, both in omission (studies hidden) and commission (studies published). Every time, new forms of disclosure and new types of barriers are created in order to diminish the chance of a recurrence.

Efforts to eliminate or at least make known such conflicts have been underway for decades. Currently, the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) guidelines state the following:

All participants in the peer-review and publication process must disclose all relationships that could be viewed as potential conflicts of interest.

BMC currently lists 389 sponsoring members in 42 countries. Of these, 10 are commercial entities:

- Beijin Hanmi Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. (China)

- Shenzhen Beike BioTech (China)

- Sanofi Pasteur MSD (France)

- Bayer Animal Healthcare (Germany)

- Bayer Pharma/Bayer Healthcare AG (Germany)

- Berlin Chemie AG (Germany)

- Novartis Group (Switzerland)

- Hershey Center for Health and Nutrition (US)

- Isis Pharmaceuticals (US)

- Group Research and Development Centre — British-American Tobacco (UK)

While it’s unclear what each corporation pays, BMC offers a few options — pay to have all author fees covered; pay to cover half of the fee, leaving the other half for the author to cover; or pay an annual fee that provides a 15% discount to your authors.

Of the 10 corporations sponsoring authorship in BMC, six cover all author costs (representing 60% of the group), one covers 50% (10%), and three provide the 15% discount to their authors (30%).

Comparing this to the institutions in four countries without any corporate sponsors — Australia, Spain, Sweden, and the Netherlands (chosen primarily because they have a high number of participants in this program) — the percentages reverse for this purely academic/foundation market: 28% provide full sponsorship, 4% provide 50% sponsorship, and 68% provide the 15% discount option.

This suggests that corporations are willing to spend more to fully sponsor their authors.

How directly are the research initiatives tied to corporate goals? It’s unclear, but the Hershey Center for Health and Nutrition®’s entry on BioMed Central concludes with this sentence:

The results of these investigations guide product development for The Hershey Company.

If BMC were dancing only with big chocolate, we might only have to worry about obesity, diabetes, and cavities. (It should be noted that the Hershey Center has published only one paper on BMC to-date.) But with pharmaceuticals and tobacco represented on the list as well, the stakes are higher.

There are three major questions in play with BMC’s approach to allowing corporate sponsorship of research publication fees:

- Is a company sponsoring an author’s fees creating a conflict? This is a more complicated question than it seems. In the case of BMC, the corporate sponsorship encompasses not particular papers but any papers produced by that company’s researchers during the term of the sponsorship. Is that direct enough to constitute a conflict? For whom is it a conflict? The authors? Or BMC?

- What should be disclosed, to whom, and when? In the papers I came across, the disclosure of sponsored author fees was non-existent. Of course, with some sleuthing, you could find out about this BMC program and see a list of the papers sponsored under such arrangements, but a clear, simple disclosure for the reader doesn’t seem to exist.

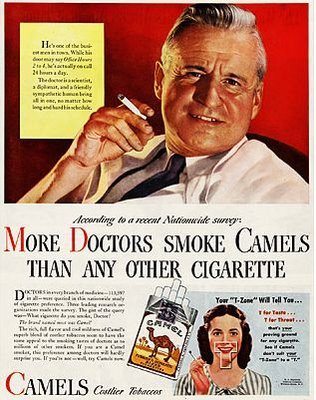

- Is a tobacco company qualitatively different from any other corporation? Generally, medical journals have categorized a few types of sponsorship as off-limits — tobacco, firearms, and alcohol. And while wine has been found to have some health benefits, the same can’t be said for bullets or cigarettes.

As an industry, we’ve grappled with how to disclose, prevent, or compartmentalize various flows of interested money into scholarly publishing. Advertising policies create zones and clear boundaries for advertisements. Author disclosures help reveal potential competing interests authors may possess. Scandals like the Elsevier fake journals episode exhibit the kind of justifiably righteous firestorm that occurs when these boundaries are crossed.

But we don’t seem to have grappled with the corporate sponsorship of author fees for OA publications.

In order to learn better whether I was seeing something new, I asked Deborah Kahn, Publishing Director at BMC, a set of questions related to corporate author sponsorships:

- What is the approximate range for each sponsorship in US$ or Euros?

- Are these annual sponsorships?

- Do you have sales people selling these sponsorships?

- Is there a different rate for academic vs. corporate sponsors? What determines the rate?

- Have you contemplated disclosures around these sponsorships?

- What are your editors told about these sponsorships?

- In the case of the tobacco company sponsorship, did you approach them or did they approach BMC?

- Are there industries you would not sell a sponsorship to, on moral or ethical grounds?

- Was there any internal controversy when the tobacco company joined the program?

- When a paper is covered by one of these arrangements (academic or corporate), how is that reflected in your editorial systems?

I sent the request at around 7 a.m. ET. I’d heard nothing in reply before this post was finished (10:15 p.m. ET 1 May 2012).

Of course, the researchers using these sponsorships are employed by the companies providing them. Yet, in most of the papers I reviewed stemming from these sponsorships, authors stated that no conflicts existed. Most mentioned that they were employed at the relevant company at the time.

Publication planning is one concern here. If a company can establish some groundwork with a few baseline papers in the literature, it can build on those with stronger journals, and ultimately create the impression of a body of literature fomented by strategic publication planning. But even without that kind of conspiracy theory, there seems to be no reason not to disclose this extra money being paid to the publisher to facilitate publication.

To me, the addition of a tobacco company to this list was especially worrisome. Cigarettes and other recreational tobacco products add nothing to health or vitality, so any science related to them seems to be about fooling people into doing something against their own best interests. For my own full disclosure, I should add that cigarette smoking took my Dad’s life prematurely. He died of lung cancer related to a lifetime of smoking at the age of 61, far too early. So I have a muted but real bias against cigarette companies and their products.

Regardless, I tried to think of an analog for this type of payment to publishers — one that has the peculiar characteristics of giving the publisher a lump sum to cover publication costs incurred by researchers the payer employs, in a manner currently requiring no disclosure. I couldn’t think of an analog. This seems like a new beast.

A disclosure could be as simple and straightforward as, “This paper’s publication fees were paid/subsidized by a sponsorship from Company X.”

The more I thought about the BMC arrangement allowing corporations cover or subsidize OA publication fees, the more I began to feel this constitutes an arrangement that should be, at the very least, disclosed clearly to readers. Moreover, it seems to be a new approach to corporate sponsorship of authors and their works, one that I haven’t seen contemplated in statements around conflicts of interest.

OA is a relatively new paradigm of publishing, and should be held to the same high standards of transparency and rigor we all strive to maintain. Corporate payments to publishers to cover or subsidize corporate author fees is a new and potentially problematic approach to funding the literature. We need to understand it, and set expectations about how it should be handled.

Discussion

30 Thoughts on "Where There's Smoke — Is Sponsorship of Open Access Author Fees a New Type of Conflict of Interest?"

It is generally accepted that most author fees will be paid by the funders. This is usually assumed to mean from the grant funds, but sponsorship simplifies the process, so it seems like a good idea.

The government and universities are just as capable of manipulating science to further their goals as industry is, so your proposal should be that all fee funding is a potential conflict of interest, which should be disclosed. Sponsorship per se is not the issue. But if someone is paying a million dollars for research, does it really matter if they pay a thousand for publication? I have trouble seeing this as a real problem.

As an aside, the idea that cigarette companies cannot do, or should not publish, science is unsupportable. A lot of people smoke and research can improve that experience, or even make it safer (even if not safe). Would you censor all research related to unsafe activities?

If disclosure is meant to yield transparency, then who is paying author fees should be disclosed. It might help readers evaluate a paper, and understand whether the authors had their research funded but not their author fees (which would suggest to me that the authors were slightly more independent), or if the authors had their research funded as well as their author fees, which suggests less independence to me.

I agree that funding of author fees overall should be disclosed. I picked up on these 10 companies because corporate interests are more of a concern. But I also think disclosure should be considered for author fees of all types. Who is paying the freight? It’s worth disclosing.

The point I was making about cigarette companies is that publishers shouldn’t be accepting money from them. Elsevier, Oxford, and others were criticized for investing (not receiving direct payments from, but investing in funds featuring) arms companies. BMC is taking money directly from the world’s second-largest tobacco company. That seems wrong. Cigarette/tobacco research is in my mind obvious and flimsy, but it can be published. A publisher taking money from a tobacco company? Nah.

This may be an interesting piece to read, in regard of disclosure:

Richard Smith: Disclosure of conflicts of interest may increase bias

http://bit.ly/IlLKX3

Kent – I have just been alerted to this post. I have not received an email from you. Please resend and we will respond. Deborah

If we believe that BMC sufficiently insulates its editorial decision-making from its business practices, then the effect of industry sponsorship of author publication charges is creating a dissemination bias, whereby the results of pro-industry results have an advantage over reaching readers. In a full OA journal, however, this tenet is problematic, since the source of sponsorship has no baring on access — all articles are freely available.

In a hybrid publication model, where a surcharge can be paid to make an article freely available upon publication, an access bias is very possible when industry pays for OA fees. Jakobsen and others (BMJ, 2010) reported that industry-sponsored articles were more than twice as likely to have paid OA publication fees in a hybrid journal. They write:

Our results show that author-paid open access publishing preferentially increases accessibility to studies funded by industry. This could favour dissemination of pro-industry results. We suggest the term e-publication bias for this emerging type of publication bias in open access hybrid journals

Jakobsen AK, Christensen R, Persson R, Bartels EM, Kristensen LE. 2010. Open access publishing. And now, e-publication bias. BMJ 340: c2243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c2243

As you note, this is probably only true for hybrids. The far deeper issue is that under a funder pays regime the power of the customer shifts from readers to funders. Funders have very different needs and interests from readers. People who think OA will benefit readers might want to think about this dynamic.

All the more reason to be clear about where money is entering the system, what it’s paying for, and whose money it is. If the author-pays model (aka, funder-pays model) continues to grow and be promoted by governments as some panacea, it will need to mature into a truly transparent system and not the rather opaque and idealized system it is today.

May I assume that buying large numbers of reprints of an article in, say, the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, by the pharmaceutical industry or prosthetics manufacurers in order to disseminate them amongst practitioners is also a practice severely frowned upon? Would be logical.

Distribution is different and occurs later than publication, with works that are finished. We do sell reprints, as do most journals. We want to get the information out. But we don’t accept money from industry in order to make publication from their researchers cheaper (we don’t charge anyone to publish with us), and there is no deal-making prior to publication at all.

Also, recipients of reprints know who has sponsored the distribution. There is transparency. There is not the same level of transparency for articles published on BMC with this kind of sponsored fee approach.

This issue Jan Velterop points out is in fact a conflict of interest. Publishers stand to make a lot of money selling reprints based on a journal’s decision to publish a manuscript describing a trial that finds a particular drug or device works better than the standard treatment. Selling reprints tends to be a highly profitable and it is hard to think of a better marketing tool for a manufacturer or pharmaceutical company than a published study showing their drug or device is better than the competition.

It is not just the recipients of the reprints who should be aware of this, but all readers. The crux of the issue is the potential influence or the appearance of an influence on the decision to publish the manuscript based on a financial gain for the publisher, just as with BMC’s system for sponsoring institutions to cover publication fees.

It is true this conflict is transparent though I suspect many readers have never thought of it. But then BMC publishes a list of their sponsors and as you noted, authors generally list their employers which provides a similar level of transparency.

If you expect BMC to report the details of their financial arrangement with each sponsor, it would seem subscription publishers would have a similar obligation report their sales to the manufactures or pharmaceutical companies who purchase reprints of studies concerning the products they sell.

Reprints are a different beast. Here’s why. First, the same drivers that you’d attribute to reprint sales act as incentives for reader-oriented editors — impact factor, novelty, relevance, scientific interest. Second, reprint sales occur after editorial selection and publication. Third, there is no direct association between editorial selection and reprint sales — that is, the market for reprints is fickle and unpredictable and outside of a publisher’s control, so budgeting for reprint revenues tends to be conservative (low). Third, reprints are highly constrained by all sorts of rules, both particular to potential buyers and in some cases by venue (state or national laws).

Most publishers shield their editors from financial information in general. Reprints are usually a fairly small line item in most budgets, so awareness of this line of business is often very low or non-existent in the editorial space.

Meanwhile, what we’re talking about here occurs prior to publication, seems to have the potential to skew the literature toward commercial interests by front-loading it in that manner (remember, a majority of corporate sponsors at BMC provide 100% sponsorship, while a minority of academic sponsors do). And there is no disclosure about what’s being paid. It’s farther upstream, more reliable revenue, more likely to be mistaken for a quid pro quo. It needs to be handled more carefully than a post-publication distribution event that’s unpredictable and relatively minor in scale.

I suspect BMC also shields the editors that are employees and I believe most if not all of the BMC series journals are now using volunteer section and associate editors to manage the review process and make publication decisions so they have no financial stake at all. The peer review is also open with the reviews and revision process published with the article providing a further level of transparency.

As David points out, sponsorship by a university or government as the author’s employer could raise similar questions of conflict of interest. Now it is true that for a very long time universities have been approached by university presses to provide subsidies for publication of some monographs. But this approach is only made (usually) after a manuscript has been put through the formal review process, or at least initially vetted by an acquiring editor and found to be suitable for the press’s list and meritorious as a contribution to scholarship. What is troubling about the kind of arrangement that Kent points out is that if this same kind of arrangement is offered by universities to their faculty and this is known in advance to publishers using an OA model, only those authors at such institutions may find that their submissions are given serious consideration, and then we’ll be in a situation of where the “rich get richer” and only those wealthy institutions that can afford to provide OA fees to all faculty will be able to get their faculty’s writings, as books or journal articles, published.

Kent,

To refer to payment of publication fees by BioMed Central member institutions as ‘sponsorship’ or ‘subsidy’ is misleading.

Corporations (along with universities and funders) are one of the types of organization which carry out and/or fund research and which publish that research in peer-reviewed journals. When publishing in an open access journal, a publication fee is generally payable, and BioMed Central membership is simply one of the mechanisms by which that payment may be covered. Membership is effectively an institutional account, and many organizations take advantage of membership accounts to minimize administration, and to reduce financial barriers to authors considering the open access publication option. But whether an author fee is paid centrally from the institutional account, or directly by the author using funds which they reclaim from the institution/funder, is surely incidental.

In terms of transparency, authors are required to acknowledge external sources of funding for their research costs, including open access publication fees. So if a corporation has covered the publication cost for an article, the involvement of that organization in funding/carrying out the research, including the open access publication fee, will be visible as either an affiliation (for research carried out by employees of a corporation), and/or an acknowledgement (for external funding of academic research).

A key reason that BioMed Central introduced its membership scheme was to help level the playing field between open access and subscription journals. In the absence of central institutional support for open access publication fees, but with large-scale institutional financing going instead into library serials budgets, authors were effectively being given a strong financial incentive to publish in subscription-based journals. To address this, we introduced BioMed Central membership. We have also encouraged institutions to consider setting up central open access funds (e.g. see case studies here http://www.biomedcentral.com/funding/ and additional information from SPARC here http://www.arl.org/sparc/openaccess/funds/ ), and we have been pleased to see such central funds now becoming increasingly widespread. For example, all organizations signing the Compact for Open-Access Publishing Equity http://www.oacompact.org/ have them, or are committed to creating them.

You say disclosure happens: “So if a corporation has covered the publication cost for an article, the involvement of that organization in funding/carrying out the research, including the open access publication fee, will be visible as either an affiliation (for research carried out by employees of a corporation), and/or an acknowledgement (for external funding of academic research).” Then why does this article (http://journal.chemistrycentral.com/content/5/1/15) have only this as the acknowledgement of Competing interests:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The authors work for a tobacco company.

The authors do not say that the tobacco company sponsorship paid to BMC covered their publication fees. That’s a different disclosure.

Your last paragraph is essentially saying this was all about the money — charging people was turning them off the OA model, so you needed a way to make it seem free to authors, and that was through institutional and corporate sponsorships of author fees. That’s probably quite true. But there are consequences, including disclosure. I hope BMC chooses to take a leadership position on these issues, as well.

It’s important to note that “In terms of transparency, authors are required to acknowledge EXTERNAL sources of funding for their research costs, including open access publication fees.” (emphasis mine) That is different from an institution or company that has the author(s) on their research staff and payroll. One isn’t expected to disclose that one received funding from the university one works for; that much is made clear through stating one’s affiliation. And institutional/corporate membership in BMC only permits authors who are affiliated with the member to receive a discount on article processing charges. In the example of the Chemistry Central article you cite, the author has indicated his affiliation with British American Tobacco (the BMC member) and thus isn’t required to disclose further details of what that support entails. BAT would not be permitted to “subsidize” the fee for a non-BAT affiliate.

Page charges have been around for subscription journals for a long time. Are you saying that corporations never covered these costs for their employees in the past?

To me the key question is: Did the paper go through the standard editorial process? If so, citing the author’s affiliation is tip-off enough.

Page charges and open access fees are small potatoes compared to the cost of doing the research. If we accept disclosed sponsorship of research, why are we worried about publication costs?

I see a bigger problem in a sponsor NOT automatically paying for publication costs. Withholding support could be used to suppress unfavorable findings.

Kent,

You will find a great deal of information about membership, including answers to many/most of your questions, readily available on our website:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/libraries/membership

Specific answers below:

1. What is the approximate range for each sponsorship in US$ or Euros?

Supporter memberships are annual and the pricing is based on size of institution, ranging from around $2500 to $13,000.

See: http://www.biomedcentral.com/libraries/supportermembership

Prepay membership is not annual – it functions as a deposit account, and it is up to the member how much they deposit.

Obviously, the more articles are published by researchers at an institution, the more the institution will need to deposit in order to keep the membership account in credit.

2. Are these annual sponsorships?

Supporter membership is annual, prepay membership is not.

3. Do you have sales people selling these sponsorships?

Meet our institutional sales team:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/libraries/contact_us

Since launch in 2000, BioMed Central has worked closely together with libraries to advocate the benefits of open access to researchers. The idea of memberships arose out of discussions with librarians, as a mechanism to promote open access publication and to make it as convenient and efficient as possible.

4. Is there a different rate for academic vs. corporate sponsors? What determines the rate?

As is standard practice, BioMed Central charges corporate customers a somewhat higher rate for products such as supporter membership, as compared to the academic pricing.

As noted above, supporter membership pricing (whether academic or corporate) is determined by size of institution.

5. Have you contemplated disclosures around these sponsorships?

As noted in my earlier post, membership is a means to fund the cost of OA publication, in whole or in part. As such, it is one of the costs of the research, and authors are required to acknowledge the sources of funding for their research in their article.

6. What are your editors told about these sponsorships?

BioMed Central has spent to the last decade promoting memberships to universities, funders and corporations, with the active support of our editors.

Our editors have supported memberships, as they increase awareness of open access, reduces the financial barriers for authors wishing to publish in open access journals , and help level the playing field with subscription journals (which already have strong central financial support from serials budgets).

7. In the case of the tobacco company sponsorship, did you approach them or did they approach BMC?

I believe in this case we were approached by the corporation.

8. Are there industries you would not sell a sponsorship to, on moral or ethical grounds?

This question again confuses sponsorship with payment of publication fees.

The decision to publish an article, whether from academia or the corporate sector, is made not by the publisher, but by academic editors on the basis of expert advice from independent peer reviewers.

If an article is deemed suitable for publication, then an article processing charge will be payable. This charge can be paid individually by the author, or centrally by the author’s institution (through a membership).

If institutions publish regularly in our journals, then setting up a membership is a natural choice as it makes payment easier and more efficient.

Transparency is key, and BioMed Central journals have strong policies on declarations of funding sources and of conflict of interest, and follow COPE guidelines on editorial ethics.

Many BioMed Central journals, including all the medical journals in the BMC series, use an open peer review model to offer the maximum possible level of transparency.

9. Was there any internal controversy when the tobacco company joined the program?

There is certainly a spectrum of opinion, within science publishing, as to how journal editors should treat research funded by tobacco companies.

A few journals have gone so far as to ban outright any research which has received tobacco industry funding.

Most journals, however, regard such censorship as a step too far and an infringement of freedom of speech. Instead, these journals tend strongly emphasize transparency and declaration of conflicts of interest.

The method of payment, on the other hand (individual payment, vs membership payment) has not been a source of controversy.

10. When a paper is covered by one of these arrangements (academic or

corporate), how is that reflected in your editorial systems?

Payment handling is intentionally kept distinct from, and not made visible to, the editors handling the peer review and decision-making process.

Matt,

Thanks for the answers. I have a few additional questions.

1. You say that the prepaid author fee sponsorships are deposit accounts. How much did the tobacco company put on deposit? What remains? Have you ever refunded a deposited amount because of disuse? What are your policies on refunds for these deposit accounts? Are deposits non-refundable?

2. You say that authors are required to note the sources of funding, including funding of open access fees. Yet, I can’t find disclosure that lists funding of these fees (e.g., http://journal.chemistrycentral.com/content/5/1/15) or the fact that a company may have a large amount on deposit with BMC. Can you point me to an article that discloses this? Or to a BMC page that discloses corporate deposit accounts?

3. Prepay members have access to reports of the papers in process (“Online statistics are available 24/7 to allow customers to view article submissions and publications from their organization.”) I interpret this to mean the sponsors of research papers who prepay get access to editorial status updates. Is this true?

Kent,

regarding the analogous model – I think the sponsorship model for open access (http://www.arl.org/sparc/bm~doc/incomemodels_v1.pdf) is similar in the sense that article-processing fees are covered by a (possibly) corporation, even though all authors (not only the ones employed by the sponsor) benefit from that.

I think the document you’ve pointed to talks about sponsorship slightly differently. The fees can be covered, but it’s not a straight line from company through researcher through publisher. The company sponsors a journal, so to speak, and whatever it publishes during a particular time, up to a point.