What if the only measurement of energy costs you followed was the price of oil, while everyone was shifting to cheaper and more efficient alternatives? And what if you completely ignored the fact that everything around you was using more and more power — your lights, your phone, your car, your heat, your media center? You might come to believe that energy is getting more expensive, when actually, it’s price is rising relatively slowly while your usage is what is skyrocketing.

The same thing might be happening with print journal prices and digital journal licenses.

A recent report from Paula Gantz sheds some interesting light on what’s often used to measure prices vs. what is actually driving increases in expenditures. Commissioned by the Association of American Publishers (AAP) and its Professional and Scholarly Publishing (PSP) divison, the study may be reflexively dismissed by some based solely on its source. This would be a mistake, of course. It’s a well-documented study that raises some subtle and important questions:

- What if prices of the predominant journal form have actually been falling?

- What if we’ve been measuring the wrong things, or measuring insufficiently?

- And what if the growth in expenses are not the result of price increases but a result of the growth in science?

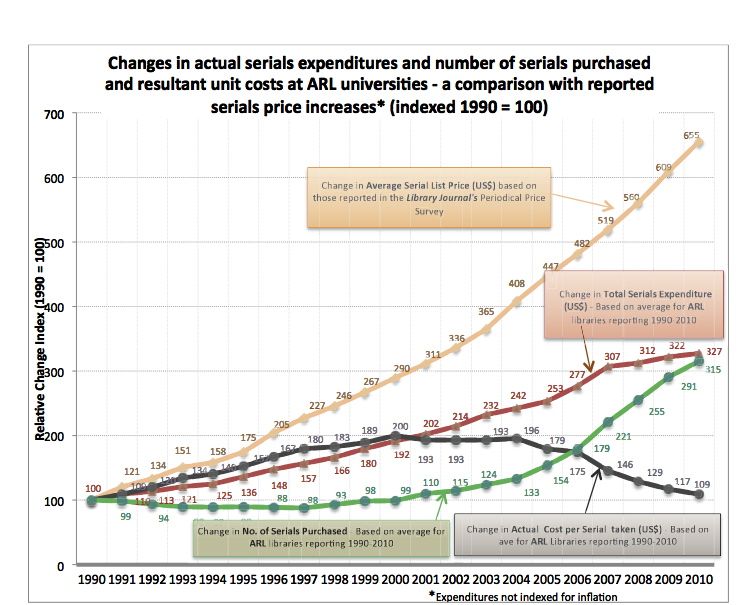

Gantz’s report starts with a fundamental observation — Library Journal’s Annual Periodical Price Surveys are all based on print subscription prices, yet most journals are now basing their core pricing and market presences on their digital versions. Print subscription prices have increased six-fold since 1990. But, as Gantz writes:

. . . using list prices of print subscriptions to calculate the real increase in serials expenditures is a misleading and inaccurate method for tracking how libraries are spending their serials budgets and fails to recognize the increased value they are receiving from the print-to-digital transition.

When the basis changes from print pricing to library expenditures — a better reflection of overall spending — a clearer correlation emerges:

. . . libraries’ spending on periodicals has increased three-fold while their collections have tripled in size through new acquisitions and through expanded content in existing holdings.

Spending three times as much to get three times as much tells a very different story from the “price increases” story. Further facts bear out the hypothesis that the growth in research outputs and researcher population is driving more research publications:

- Published article output has grown 3.5% to 4% per year since 1990

- Growth in research spending has been increasing by 3-4% per year

- In the US, spending on scientific research has more than doubled since 1990 (from $150.2 billion to $400.5 billion in 2010, in current dollars)

This all points to a massive three-fold increase in scientific outputs.

These outputs have been captured in two ways — more journals being published, and more articles being published in existing journals.

Gantz notes how pages have increased in many core journals, doubling in some cases. This has occurred as these same publishers have launched new titles to deal with the growth in scientific outputs.

Ultimately, the root cause of larger information expenditures is a growth in research funding, researcher numbers, and research-driven careers.

In the midst of all this growth, prices have risen modestly. Gantz notes that while the economy in the US from 1990 to 2010 grew at a compounded rate of 66.8% due to inflation, the effective price of an average journal is only 9% higher over the same time period. In the UK, prices have actually gone down by 11% since 2004.

Price increases have been caused by more science, more papers, and more journals, not by price increases in licenses. In fact, per-journal prices seem to have peaked around 2000, and steadily declined from there, as shown by the black line in the chart below.

Usage is outstripping articles produced, as well, making prices per article within licenses fall on a per-usage basis. This increased usage has led to exactly the kind of behaviors everyone believes is good for science — researchers are reading more, citing more, and citing from more sources. On a cost basis, the price per download in the UK fell from £1.19 in 2004 to £0.70 in 2008.

Therefore, Gantz believes, if we were to actually measure the true cost of licensing information at libraries, focusing on three things — overall expenditures (not just print pricing), the amount of information licenses provide, and usage — prices have actually increased only slightly, and in some cases have decreased.

There are a few interesting dynamics around print prices I believe. Gantz didn’t feel confident speculating about these, she told me in an email exchange I had with her, but I write a blog, so I get to speculate. I think print pricing is a dubious baseline for one or more of the following reasons:

- the practice among many publishers of increasing print prices rapidly in order to discourage the purchase of print

- the increase in per-copy costs that smaller print runs dictate — so, as print dies, it gets more expensive to produce

- the view that print is superfluous given all that online licenses provide, so charging more for it is fair — you really have to want to have it, and if you do, you’re willing to pay a higher price

Print is no longer “market price.” Its pricing is being driven by non-market factors.

Gantz’s analysis raises interesting questions. What if we’ve been misled by following the wrong price trends? What if the strain around expenditures is more about institutions not supporting the growth in science than about publishers seeking to exploit some advantage? What if publishers have been more responsive to the growth in science — by creating new and larger venues for scientists — than institutional information budgets have been?

Gantz’s numbers raise another very important possibility — that publishers are putting themselves in an unsustainable position. After all, if an economy grows by at a compounded rate of 66.8% over 20 years and your pricing only increases 9% per title on average over the same period, the arithmetic is pretty clear — you have $109 dollars to buy $166.80 worth of goods. It may be that the exaggerated pricing of print has allowed the lower prices of digital licenses to some extent.

An encouraging note to all this is that there seems to be an obvious path forward — namely, fewer print titles and better support for valuable and well-used digital licenses.

Discussion

17 Thoughts on "Have Journal Prices Really Increased Much in the Digital Age?"

“Gantz’s numbers raise another very important possibility — that publishers are putting themselves in an unsustainable position. After all, if an economy grows by at a compounded rate of 66.8% over 20 years and your pricing only increases 9% per title on average over the same period, the arithmetic is pretty clear — you have $109 dollars to buy $166.80 worth of goods. It may be that the exaggerated pricing of print has allowed the lower prices of digital licenses to some extent.”

I’m having some difficulty believing these numbers. The 66.8% increase must be the cumulative increase for the full 20 years. I’m not exactly sure what “compounded” means in this sentence since this term is usually used with annual price increases rather than a fixed increase over a number of years. To be comparable, the 9% increase must also be for the same period. The article describes the 9% as the “effective price” and the graph refers to it as “the actual cost per serial.” Would you provide some additional information on how the study defined these two terms that appear to be the same? Is this calculated on the number of pages, number of articles, number of words, or some other measurement?

Other issue include the “big deal” where libraries purchase large packages including some titles that they didn’t really want. Finally, how does variable pricing fit into this analysis since libraries often pay different prices for the same packages according to size, number of seats, and possibly other factors?

The list price print model may be a fiction as you say above, but it made price comparisons easy. The new model from this study would force, as you say, a radical rethinking about the economics of scholarly communication.

“Compounded” means cumulative, in your parlance. It means the the principal at the beginning is increased by the interest rate, and this increase becomes part of the principal that is increased in the next period by the interest rate. I’m sure you’ve encountered this before in your mortgage, car payment, or other settings. The 9% increase is for the same period, as you can see by the chart. Gantz’s point is that the inflation rate (compounded over 20 years) of 66.8% isn’t taken into account to the 9% increase, which is not inflation-adjusted.

I completely agree with your last two sentences.

Something seems to be let aside in this analysis: if the number of researcher grows, then the number of readers grows too, so that the number of downloads grows much faster than the the number of articles: if every researcher in a community writes one article per year and reads every article written in this period, with 10 researcher you have 100 downloads while with 20 researchers you get 400. Since the cost per download is very low compared with the fixed cost per article (copy-editing, peer-review, etc.) and the overall fixed cost (web platform designing, etc.), it is difficult to estimate what would be a fair evolution of the price per download during an increase of the size of the research world. I would bet it should decrease much faster than it does, given the quadratic effect described above and the profits of the STM publishing.

Moreover, I wonder whether the averages presented in the chart are weighted (e.g. in terms of the number of article per year for each serial) ; if not, it makes these figures very difficult to interpret: if publishers where splitting every journal in two series, keeping the total price unchanged, it would appear as a dramatic fall in prices. Even if this is not happening, for a given amount of research articles distributed, unweighted averages do not behave in the same way if the increase of already existing serials outweighs the creation of new ones or the other way round.

I mention this in the post. It is also explored more in Gantz’s report. I’d recommend you read it.

There is at least a contradiction with your penultimate paragraph: prices can go down while revenues and profit of publishers go up, simply because the demand is growing and the marginal cost is small. I therefore do not understand how you deduce that current pricing is likely to put publishers in danger (especially since current pricing induces comfortable profit).

The point is that an organization can lose ground within a larger economy if its prices don’t remain on-par with prices for other things in that same economy. You can increase you salary with a 1% raise every year, but if inflation is 3%, you’ll feel a lot poorer after 20 years.

Your example shows you did not understand my point, which is not about the distinction between real and nominal values.

If publishers sell, per article, 3 times as many downloads at 0,7£ each than they did at 1.29£ a while ago, and if the total (real) cost of producing these downloads has not raised much, then they are largely enhancing their profit. The number 3 might be overestimated, but my point is that growth of demand and small marginal cost to the producer combine so that sustainability can be achieved even with diminishing prices.

So, “we make it up in volume” is your premise? I don’t think so. First, publishers aren’t selling per-download, but selling at a set price. The per-download cost uses that price as the denominator of the calculation. It is nothing more. Usage doesn’t drive pricing like you’re supposing it does. Usage happens within pricing, and pricing hasn’t gone up much. That’s the point.

At this point, the only reasonable way to measure prices is at the article level. Many journals have gotten bigger–some very large (e.g. PNAS, JACS, PLoS ONE). And most academic libraries have been purchasing publisher packages (aka “big deals”) for over a decade. While the journal title still has value conveying value to the reader, it has almost no remaining relevancy to the acquisitions librarian who is paying the bill.

Acquisitions librarians are, believe me, still paying lots of bills for individual journal subscriptions, despite the fact that most are also paying for journal packages. At this point, it may be true that the only reasonable way of measuring value is at the article level, but the only reasonable way to measure price is at either the title or package level–because that’s the level at which prices are set and content is typically purchased. (Article-level purchasing happens too, but it’s still very much the exception to the acquisition rule.) And, as I’ve said over and over in this forum, it’s price in the context of budget that determines affordability. Value has nothing to do with affordability.

This analysis suggests that OA will be no solution at all to the increasing cost of scholarly communication because every article published will need to be paid for up front, either directly through an author-side payment or through some form of institutional subsidy for the journal as a whole, and if those articles are increasing in number at the rate this study shows, then overall costs will increase proportionately. In fact, the burden on universities is likely to be greater than it is in the TA model because there can be no “big deal” for OA payments and no discretion for universities not to pay for their faculty’s publications as they have discretion not to subscribe to TA journals. (If they start trying to triage among faculty publications, all hell will break loose.)

At least at my institution, this is certainly not the case. The author’s fee for publication is paid by the PI concerned, and comes out of his/her research budget. Hence the institute does not pay for faculty publications, and it is entirely up to the individual PI if he/she wishes to spend research funds on author fees for publication.

When librarians want to talk about price, publishers usually try to divert attention to what they call “value” – as Gantz does. “But online is so wonderful! Scholars love us! You get so much more!” I agree the two have nothing to do with each other. With bundling and packages, all the extra content is really neither here nor there unless you ask libraries whether they *want* that extra content, in the sense that they’d willingly pay for it on its own merits if they had the budget to do so. I think in many cases the answer there would be no. A lot of any publisher’s bundle is dross, no matter what the publisher might say in its marketing boilerplate. That applies to giants as well as prestigious societies. Every bundle has a long tail.

And I should point out that a current year’s subscription to content should not be linked directly to downloading of a title/bundle’s entire archival content. Only a small percentage of usage comes from the current year’s articles, yet publishers never share that data with us. The past content has already been bought and (in most cases) would continue to be accessible if a library dropped its current subscription. Downloads from that segment should not be included in a true cost-per-use analysis.

I don’t think this is fair. Gantz’s analysis focuses on usage as a driver of cost, and notes how usage has increased. Do libraries “want” that content? They do if their users use it.

I think your comment about budgets is much more to the point. Why aren’t the budgets there? Universities rely more than ever on research funding, yet their increases to library budgets have been lagging. Science outputs are surging, universities are benefiting, but university administrators are still turning over a lower and lower percentage of their total budget to library acquisitions. Why is that?

I doubt any would disagree that basing conversations on print-only data is outdated and unproductive to conversations on scholarly communication costs. However, I would like to see more discussion by Gantz into how the ARL statistics are collected before drawing conclusions that avg. serial cost has only increased 9%. From my understanding, there is no set method for libraries to collect total number of journals purchased. I would even be hesitant to assume that the number reported, by all schools, is actually those purchased and not those available (e.g., number may include the 8500+ journals from DOAJ). Additionally, libraries, I think, view those journals actually purchased directly, or through package deals, differently than those made available through aggregated databases (such as Academic Search), specifically in regards to indexed journals in those databases, which may also be included in the purchased number.

When looking at the raw data, I feel we need a more robust discussion before accepting that there has only been a 9% increase in avg cost of serials. From, 2000 to 2009, Yale, for example, increased # of journals by 31,240 while reducing their budget by roughly $900,000. Noticeable trends, such as this, emphasize the need to parse the data and more fully understand “behind the scenes”.