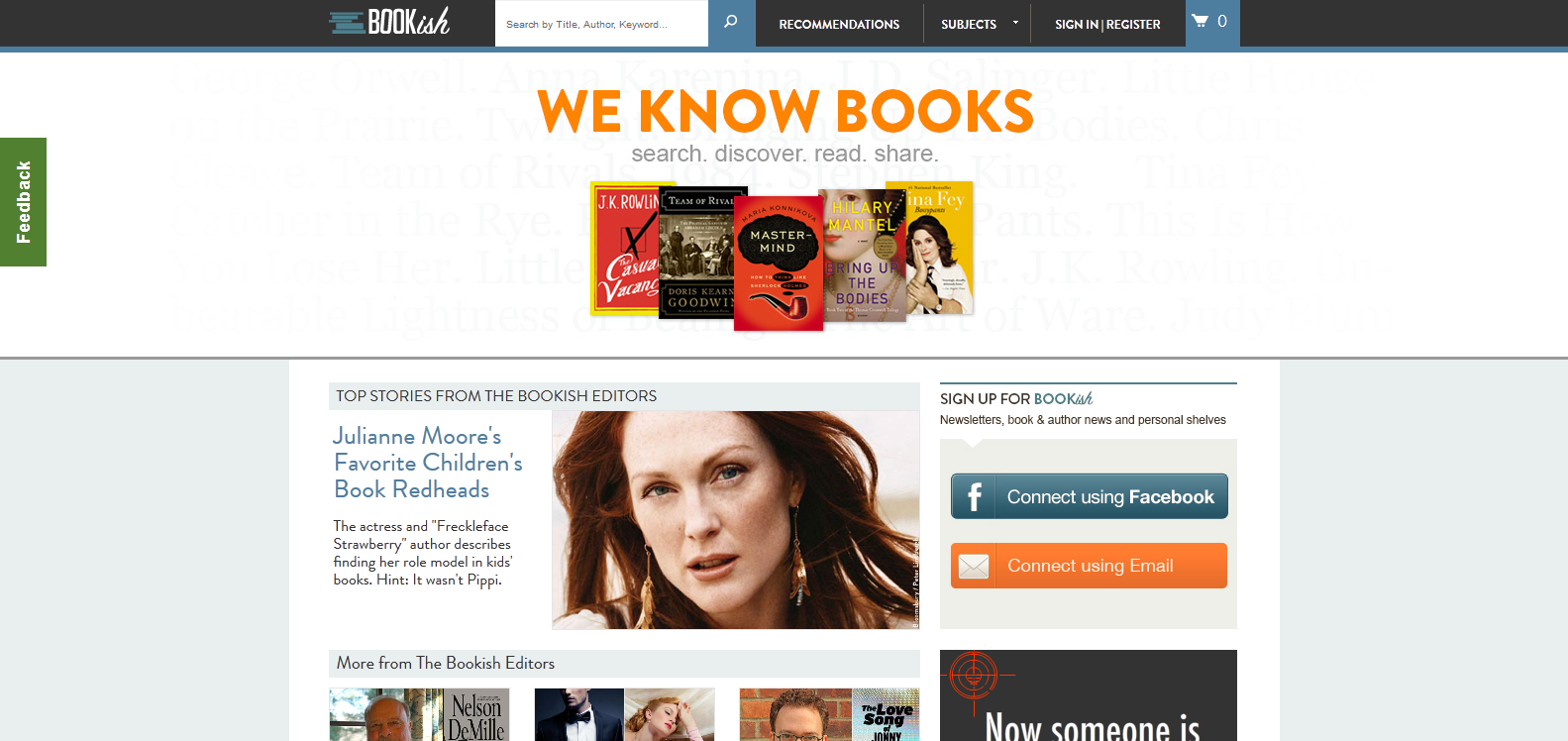

Bookish is a new online service for discovering and purchasing books. It’s a joint venture of three of the largest trade publishers: Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Penguin. (Penguin will shortly be merging with Random House.) While the title coverage of Bookish will only overlap slightly with academic publishers (though more than many people think), and its success is anything but assured, Bookish nonetheless provides some useful lessons for scholarly publishers as they attempt to navigate a shifting landscape. I have been advocating for some time for university presses to create an online bookstore, and with Bookish as an example, maybe they will.

Bookish was brought into existence primarily for three reasons: to counter the growing dominance of Amazon in consumer publishing; to offset the collapse of the bricks-and-mortar bookstore sales channel, which is making it harder and harder for people to discover new books; and just because. The “just because” reason is the most important as a spirit of persistent experimentation is the only real defense against rivals and a changing environment. And that’s the first lesson to be drawn from Bookish: someone set out to do it, and we should, too. In leading an organization, the most important thing is not to have a destination but to know you have to get on the road in the first place.

Even before Bookish launched, it had its share of critics. This is not surprising, as schadenfreude is the defining emotion of the trade publishing business. But some of the criticisms were wide of the mark. For example, Bookish can’t really outdo Amazon. This is silly: trade book publishers derive anywhere from 25% to 50% of their revenue from Amazon, and the last thing they want is for Amazon to go away. An alternative to Amazon need not be a replacement for Amazon; when you order the fish, it does not mean that you don’t like the chicken. Or it’s said that Bookish will not be able to field a comprehensive catalogue — but it already has 2 million titles (how many books did you read last year?). While the size of a catalogue has a certain appeal (more is always better), most titles in a catalogue of that size will have little or even no sales activity over a span of 12 months, and this is true for Amazon as well as Kobo, Barnes & Noble, Google Ebooks, Apple’s iBookstore, and Bookish. The Long Tail is vastly overrated. And, of course — of course — publishers can’t succeed with an online bookstore because they know nothing about retail. Is it my imagination, or is publishing the only area of our society where it is taken for granted that people cannot grow and learn? That’s why we publish all those new books stuffed with new ideas every year, to keep on thinking the same old ideas in the same old ways. And if we have not already consigned Bookish to the trash heap, let’s not forget that Bookish, which is now on its third CEO, is incompetent. People who make that remark display their ignorance of the world of start-ups. Few get it right the first time, few get it right the second time. A start-up is not a carefully articulated plan, replete with a stack of spreadsheets and high-priced market research (the biggest waste of money anywhere); a start-up is often an inchoate impulse, a felt need to fill a gap that is perceived just at the horizon. If we knew what a start-up would look like when it grew up, we wouldn’t have to start it up; it would be here already.

Bookish, in other words, can teach us things even if it fails.The first lesson is simply that it can be done — that is, it’s possible to create a joint venture, collaborating with rivals to build common infrastructure. This happens all the time in publishing (CCC, CourseSmart, CrossRef) and it’s great. It would be nice to think that we could get, say, the university presses at California, Duke, and MIT — or, if you prefer, Harvard, Princeton, and Nebraska — to join hands, with anti-trust lawyers everywhere present, and build something that would enhance their businesses even as it created a platform for the scholarly community as a whole.

If the JV is step one, step two, with Bookish as the precedent, is to invite everyone else in. The key point here is that it is impossible to get community support to start anything, but once its existence is inevitable, almost everyone joins. From a marketing point of view, not having titles from just about every publisher of any size would turn away consumers when they could not find books they had just heard about on the radio or Twitter. In the scholarly world, those invited in would eventually include every university press, every not-for-profit publisher of scholarly books, and even commercial firms (e.g., Palgrave Macmillan) that publish in the same general area.

The most important tactical lesson from Bookish is its arrangement with Baker & Taylor. B&T will provide fulfillment for print titles, shipping them directly to consumers. This, by the way, is precisely what Amazon does (with Ingram as well as B&T). When you order a print book from Amazon, sometimes it is shipped from an Amazon warehouse, but much of the time it comes from the B&T or Ingram warehouse, with an Amazon label on the box. Bookish is cleverly avoiding the headache of operating its own warehouse and distribution facility, something that anyone who wants to start an online bookstore could easily copy. There are strategic benefits of this as well. By working with B&T, Bookish has access to all the book inventory there is and the individual publishers have nothing to say about it. In the scholarly world this means that reluctant presses could nevertheless be included, as everybody sells books to B&T.

For e-books Bookish has announced that “coming soon” will be ereading apps for mobile devices. Here again it’s important to recognize what Bookish does not have to do. It’s not necessary to have a Bookish physical device. A customer will be able to download a reading app from the Apple app store or from Google Play for Android and then be able to display ebooks on any iOS or Android device. We don’t know the origin of these apps, but it is likely that Bookish is not building them itself. It’s more likely that they have contracted with a white label provider, cleverly sewing together pieces of infrastructure from multiple parties into a single branded service.

Nor is Bookish stubbornly insisting that it is first and last a bookstore. It invites users to order directly, but if they prefer to purchase books from Amazon, B&N, Kobo, or anywhere else, links are provided. Note the flow of the money. Publishers make money when they ship books to B&T. Publishers make money when they ship books or authorize ebooks to Amazon, the iBookstore, etc. Bookish makes money when it resells a book, whether in print or digital form. And Bookish makes money when it refers a user to a third-party retail operation. Bookish’s business is to facilitate the sale of books, not necessarily to sell the books itself or always to pursue the highest margin.

Sure, I have reservations about Bookish. To begin with, Bookish continues the long tradition of presenting books online with their covers or jackets as though they were face-out in a physical bookstore. This is simply nuts. It’s almost impossible to make out these covers online. Alas, there is a print precedent as well, where you can turn to the pages of the New York Review of Books and see advertisement after advertisement of university press books depicting illegible covers. Cover art was created with the physical bookstore in mind. Surely there are better ways to capture the attention of online users than by mimicking (poorly) what they might find in a bricks-and-mortar bookstore, assuming you could find such a bookstore and that it stocked scholarly monographs.

It’s the recommendation engine that is most disappointing. I am not a big fan of such things, as they always turn up things that I simply don’t want and would never want. I find Amazon’s recommendations to be worse than useless, and NetFlix’s are terrible, too. Recommending media is very hard to do. Netflix, after noting that I had seen Wim Wenders’ “The American Friend,” recommended Wenders’ “Wings of Desire.” Good hit. But then it went on to recommend “City of Angels,” a Hollywood remake of “Wings of Desire.” You got the wrong guy, buddy. Bookish’s recommendations turn up books that are in the wrong genre and even in the wrong language. Here, scholarly publishers could do a much better job, mining bibliographies and Library of Congress classifications.

Bookish is a good example of what can be done, and now that we see that it can be done, we should do it. There is a need for an online bookstore for scholarly books, and all the pieces to create such a venue are now ready to go.

Discussion

14 Thoughts on "What Scholarly Publishers Can Learn from Bookish"

Didn’t the Association of American University Presses set up an online joint catalog of books some years ago? Whatever happened to that?

Yes, and Joe knows this. It was called the AAUP Online Catalogue and was the brainchild of Chuck Creesy (Princeton), Bruce Barton (Chicago), and Michael Jensen (National Academies Press), who earned themselves the AAUP Constituency Award in part for their work on this project. It preceded both Google and Amazon, and its demise is related to the rise of both of those gargantuan enterprises.

The author may hate the Amazon recommendation engine, but that’s not a unanimous opinion. I’ve been talking to scientists recently as part of a consulting engagement, and a couple of them have told me that they sometimes find valuable professional references as a result of Amazon recommendations. So maybe Amazon isn’t great at finding the next novel for your night table, but in some cases it will guide you to the quantum physics book you’ve always needed.

Joe — thanks for this piece. I have read a lot of articles on Bookish and yours is the most balanced. It is wonderful to see Bookish launched. It is normal to have hiccups. It also can be a success if it increases eBook sales. It will never overtake Amazon, but it doesn’t need to.

Why limit it to just scholarly publications. Conferences, education, manuals, standards. There are a number of “white-label” service providers that can pull together the eCommerce site, ordering and fulfillment, limited warehousing, digital downloads and print-on-demand all to keep costs very transactional – most costs don’t occur until someone buys.

You list Amazon, but do not mention E Bay and the notorious partner PAYPAL who keep back funds received never to be returned.

Also is this another USA controlled company registered in Luxembourg which avoids paying tax ?

Where do other publishers fit in to the venture. An announcement would be helpful.

Joseph: Thank you for this timely, informative report. It’s a captivating concept for this novelist, me, whose main protagonist is history itself through the eyes of fictional characters. I encourage you to persevere in your Bookish strategy.

Joe talks about university presses setting up a Bookish-like system, but he knows that this was already tried (see comment above). There is a challenge here Joe does not mention, however: if this is to be a comprehensive database of scholarly books, it will have to extend well beyond university presses, but then the problems of getting it up and running and managing it become much more complicated since it would not be solely an AAUP project. If it were just an AAUP project, however, it would have to provide for delivery of books from overseas AAUP-member presses, which Baker & Taylor probably does not service. Still, I agree with Joe that the idea is worth exploring again as university presses are not well served by having to rely on Amazon alone.

An interesting article – love to hear about new ventures coming into this space.

One question about Bookish came to mind reading the article the second time, though; what is it about all the points in Bookish’s favor here, that couldn’t be said about literally any concept at all?