The novelist Iain Pears has just published a fascinating column in the Guardian entitled “Why You Need an App to Understand My Novel.” Readers familiar with Pears’s earlier work (An Instance of the Fingerpost, Scipio’s Dream; he also is the author of the Jonathan Argyll art history mysteries) have come to expect a degree of experimentation with how stories are put together. His latest novel, Arcadia, with its ten different narrative strands, pushes experimentation further–so far, in fact, that Pears came up against the limitations of the printed page. As he puts it in his column:

The novelist Iain Pears has just published a fascinating column in the Guardian entitled “Why You Need an App to Understand My Novel.” Readers familiar with Pears’s earlier work (An Instance of the Fingerpost, Scipio’s Dream; he also is the author of the Jonathan Argyll art history mysteries) have come to expect a degree of experimentation with how stories are put together. His latest novel, Arcadia, with its ten different narrative strands, pushes experimentation further–so far, in fact, that Pears came up against the limitations of the printed page. As he puts it in his column:

I undertook the project because I had reached the limit of my storytelling in book form and needed some new tools to get me to the next stage. I have always written novels that are complex structurally; in An Instance of the Fingerpost, published many years ago now, I told the same story four times from different points of view; The Dream of Scipio was three stories interleaved; while Stone’s Fall was three stories told backwards. All worked, but all placed quite heavy demands on the readers’ patience by requiring them to remember details often inserted hundreds of pages before, or to jump centuries at a time at regular intervals. Not surprisingly, whatever structure I chose there were some who did not like it.

And he offers a forceful critique of the current state of electronic publishing: “Ebooks are now quite venerable in computing terms, but it is striking how small an impact they have had on narrative structure; for the most part, they are still just ordinary books in a cheap format.” Before we strut about our adventures in digital media, let’s reflect on that last phrase: “just ordinary books in a cheap format.” O brave new world, which is like the old world, except that you can get it off-price at Wal-Mart.

Pears’s comments prodded me to reflect on just how little revolution there is in the digital revolution. As The Who said, “Meet the new boss/Same as the old boss”. This fact is somewhat obscured in the heavily digital world of STM journals, but even there it is misleading. The PDF is still the coin of the realm, Impact Factor is derided everywhere and worshipped by all, and the budgets of academic libraries continue to demand the greatest strategic attention. Where innovation has taken hold is not so much within the primary content type but surrounding it: altmetrics, new search and discovery tools, and data analytics.

When you look beyond the journals world, what is striking is not how extensive digital inroads are but how they stop at the wilderness of print. So, for example, the college textbook market, which seems a natural for electronic textbooks, now records about 3 percent of its unit sales as ebooks. (College publishers misleadingly report higher figures because they claim a digital sale for anything with a digital component. So a student pays $200 for a print textbook and then goes online for supplemental material. The publishers put that $200 into the digital column.) Trade publishers are running around 25-30% for ebooks, a big number but not a revolution. And that percentage varies widely by category. Linear fiction (especially young adult novels and adult commercial novels) is more heavily skewed to ebooks, but other categories, particularly books that are not straight narrative text, are less likely to be sold in electronic form. University presses, with their complex page makeup — not to mention the predilection of their owners to write in the margins — record about 15% of their sales as ebooks, a figure that is rising.

What Pears’s comments make us see is that there is no reason to publish in digital form unless that form does something that print cannot. The stringing together of multiple narratives, as in Pears’s own work, challenges the limitations of the printed page. This point is not original to Pears; I would point in particular to Julio Cortazar’s Hopscotch and John Barth’s Chimera as early experiments in the testing of the limits of the printed page. (Barth himself calls attention to the nested narratives of Tales of the Arabian Nights.) It is not the originality of Pears’s comments that are relevant here, but their timeliness, as digital technology is now ready to make these “experimental” narratives possible. (Disclosure: I am an advisor to Lithomobilus, an early-stage company that is building and marketing a software platform to enable the kind of multiple narratives Pears describes.)

What’s interesting to me about Pears’s situation is that he started with an idea and then set out to develop the tools to manifest that idea. It’s clear from his article that he was not particularly adept with digital technology and found the process of developing the app to be frustrating. I would think that most times innovation flows in the opposite direction: a new tool appears on the scene and people then learn how it can be used (that is, capability precedes innovation). Sometimes those tools are put to unambiguously positive ends; an example would be the close analysis of metadata to enhance online discovery. Sometimes the tools surprise everyone with what they make possible. Think of the digital CD in the music industry. Introduced to improve audio quality and lower costs in manufacturing and distribution, the digital nature of the CD made Napster possible. Had anyone in the music business seen that coming, we would still by purchasing LPs.

For those of us working in academic and professional publishing, the experiments of a literary writer may not seem particularly relevant. I think otherwise. One of the unfortunate aspects of STM publishing today is the assumption that we all know what an article should look like and the only meaningful questions are those about the quality of the content and the ability to find relevant pieces (and cite them and so forth). We are changing how we measure the value of articles (altmetrics) and how we find things (new discovery tools such as Google Scholar), but how has the article itself changed? The article is as much a literary form as a sonnet or an epic poem; the forms enable some things and prove unwieldy for others. I suspect that the multiple narratives of Pears’s fiction will someday find an analogue in expository writing that enables intersections of one theme or thread with another, which would provide, as it were, a new form of discovery.

In the meantime we should give Pears’s latest a chance–and then ponder its implications beyond the world of fiction. You can download the app here.

Discussion

35 Thoughts on "Looking to the Future of Narrative"

Robert Darnton envisioned a different kind of book in the electronic age back when he wrote “The New Age of the Book” for the New York Review of Books in March 1999, but aside from the experiments conducted to realize that vision in the ACLS Humanities Ebook and Gutenberg-e projects, there has not been much experimentation of this kind going on in either university press or commercial publishing, though there are some signs now that this is changing.

“… we all know what an article should look like” reminded me of one of the stories my children used to love: Everyone Knows What a Dragon Looks Like [http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/1214442.Everyone_Knows_What_a_Dragon_Looks_Like] I recommend it to the community.

The big difference I see between what Pears is doing and STM journal publishing is that the former is attempting creative expression whereas the latter is trying to communicate complex information. You get points in creative writing for being unconventional. By contrast, readers of STM articles are expecting to be passed information in a particular order and fashion, and disrupting that just gets in the way of communicating the science. There’s thus much less scope for innovating away from the PDF because you’ve got to fulfill all of the communication roles of journal articles first and then find some improvement.

The research paper is a highly evolved form. There is great convenience and time saving from having a set of conventions that is regularly followed by the literature. If I want to know a detail of the method used in an experiment, I know where in the paper I should be able to find it. There are some who think the best thing about PubMed Central is how they reformat their versions of papers from different journals into one singular identical style.

Scrambling this and going freeform would likely allow some interesting innovations but would also slow readers and decrease efficiency.

I half agree with you here. It’s true that the conventions in formatting do make it easier for researchers to find where information ought to be, once they get used to the format. Having said that, when you say that researchers know where to look for a detail of the method, that’s one area that the traditional journal conventions fall down very badly. Methods sections are badly truncated, often relying on references to previous works, with minor changes and methodological enhancements poorly documented due to space restrictions.

When a researcher wants a detail of a method so that they can replicate the experiment, the way they generally go about it is to email or call the senior author and ask them. Ideally, the scientific record should include sufficient information for replication. My personal opinion is that we know there’s room for improvement in the way that we document the scientific record when we find it being supplemented so strongly with off the record communication.

Of course, there will always be personal communication and there needs to be, but the nature of research has changes so much in the last 40 years that the humble journal article needs a little supplementation.

I agree that methods reporting is an issue, but it is not due to a change in the nature of research over the last 40 years but more due to a change in the career structure of the researcher. What has happened is that the form of the article has evolved to reflect the priorities of the research community. Over the last 40 years, there has been increasing pressure to “publish or perish” and the form of the article has evolved to support this, basically by cutting out methodological details in order to fit more articles into each issue of the journal. It’s a response to a drive for quantity that comes from the career structure chosen by the research community.

We’re now at a point where there is a nascent drive toward transparency and reproducibility. Should this hold up, we’ll see the format continue to evolve to meet those needs if they are seen as priorities over the factors driving quantity. As Derek Lowe recently wrote, if you want better, more detailed (and longer to perform) reproducible experiments, then you’re going to have fewer of them, which would alleviate the quantity pressure:

http://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2015/09/02/thoughts-on-reproducibility

I think the idea that research should be reproducible from a journal article seriously overestimates the nature of journal articles and wildly underestimates the nature of science. I think you have an important story about the difficulty of replication, David. Something about two groups in the same firm?

As for articles getting shorter, are there stats to support this?

I think the story you mean is the Bissel paper discussed here:

http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/03/26/reproducible-research-a-cautionary-tale/

I’m not sure if papers are getting shorter, but in my experience, Materials and Methods sections have.

Yes, that is it and many thanks. It got me to thinking about my own research projects and the utter impossibility of explaining the many decisions made, in a simple journal article. An article is just a brief report, often of several years of work by a sizeable team. I think that by and large the non-reproducibility issue is a blog driven fad, the new wave of skepticism.

[apologies if a repeat]

The future of narrative arrived decades ago in humanities publishing. The first digital hypertextual novel is Michael Joyce’s *afternoon, a story*, written in 1987 and published using StorySpace in 1990 by Eastgate Systems. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, which I edit, has been publishing webtexts as scholarship since January 1, 1996. The fields of electronic literature and computers-and-writing have relatively long histories of this kind of publishing, much earlier and more sustained than STM fields have had. We are building Vega, an academic publishing platform to provide some authorial, editorial, and publishing support for these kinds of projects. Vega is a Mellon-funded project that I am happy to talk about more.

Indeed, Cheryl, for that matter hypertext training systems were in widespread use in the 1980s, perhaps earlier. As I said above, the website (or webtext) is the revolutionary digital successor to the book. But we still have books, just as we still have radios. I think saying that books have not changed is missing the point of the revolution.

The issue tree is an alternative to conventional sentence-by-sentence writing. Moreover, they display the structure of the thinking as well as the unit thoughts presented in the sentences. This can be pretty powerful when conveying complex material. See my http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2013/07/10/the-issue-tree-structure-of-expressed-thought/. However, like hypertext, they take a lot more work than just stringing together sentences.

“Second verse/Same as the first.”

Actually, I appreciate the digital revolution moving slowly, if we’re asserting that it is. My fear has been that things would change so rapidly that there would be no hope of keeping up. I am a semi-retired educator with degrees in the liberal arts. I like complex literature, as I like complex movies. But I have to admit I’ve rarely assigned them (the novels or the films). I’ve usually gone with novels, poems, and other texts that I hope will be straightforward for my learners. So I guess that I would go with Pears, as summed up by Esposito, “that there is no reason to publish in digital form unless that form does something that print cannot.” For good or for ill, this feels like the next step in the revolution. Rather than simply moving text from the printed page to a page with electronic access, we use the electronic way to create from the start. I’m sure this will apply to other processes and products, too.

“To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.”

I too have mused on this topic for a while (I have just looked up a talk I gave in 2012 and reminded myself that the title was “”why is the article still dominant and what could we gain from reconstructing it” – very much in line with your point!). Certainly back then I felt that we were failing to embrace the digital / mobile revolution because articles were still broadly the same as they’d been in 1665. Now I have come a bit more round to David’s viewpoint – that the article in its relatively unchanged format continues to have its place. Even the younger researchers I speak to, while experimenting with all sorts of interesting digital and mobile information experiences, still ultimately want a nice PDF that they can squirrel away. The innovation will happen around / separately to the full text, with different ways to discover, filter, share etc – lots of untapped potential in that side of things and perhaps an easier step forward (I’m not saying that it won’t then result in creeping changes to the article itself)!

But articles are not the same as in 1665. Now I can tap my screen and read a cited article. Or tap and get related articles, not cited. Or tap and get supplemental explanation, maybe even data. Or a bio, or an explanation of a key term, etc. None of this could be done in 1965, much less 1665. The primary digital revolution is that of hyperlinking, hence http.

If one is talking about the logic presented in the article, then different issues arise. The logical structure of an article is “here is the problem, here is what we did, here is what we found and here is what it means.” The simplicity of the standard article follows from this simple logic. If one wants a different logic, a different body of reasoning, then that probably imposes an increased burden on the researcher, to be subtracted from the research. So changing the article structure means changing the reasoning presented therein, or changing the way it is presented. One would need a powerful reason to do that.

Many thanks to Joe for raising (again) a truly fundamental issue. One massive factor in the preservation of the status quo, in terms of long-form research dissemination (i.e. monographs, in the main), is the continued format and purposes of the doctoral dissertation, whether in North America or (to an even greater degree) in the UK and continental Europe. None of the occasional high-profile experiments mentioned elsewhere in the comment train seem to have ‘worked’, in the sense of providing a template that others have been able to follow or repeat, and for 98% of purposes we seem to be pretty much where we were, in format terms, at the beginning of the century. Clearly there are moves, notably within the digital humanities community, to change things, but the massively majoritarian impulses in most of literary studies, history, religious studies, philosophy and political theory (to name but five sectors) remain resolutely traditional. Without very significant changes to the nature, purpose and requirements of the doctoral thesis, I don’t see this moving any time soon – and for a whole host of professional, institutional and funder motivations. And that doctoral training and shaping continues to impact profoundly on all monographic expression, long after the awarding of a PhD.

Joe writes: “I suspect that the multiple narratives of Pears’s fiction will someday find an analogue in expository writing that enables intersections of one theme or thread with another, which would provide, as it were, a new form of discovery.”

Perhaps that “analogue” is already here for the scholarly article in Elsevier’s “Article of the Future” (http://liber.library.uu.nl/index.php/lq/article/view/URN%3ANBN%3ANL%3AUI%3A10-1-116066) and Wiley’s “Anywhere Article” (http://exchanges.wiley.com/blog/2014/02/19/the-anywhere-article-arrives/). In scholarly expository writing, the intersections are often those of “conversations” among articles, for which the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) has performed and continues to perform an innovatory spark. Consider the activity and ten aims of the Linked Content Coalition (http://www.linkedcontentcoalition.org/). It’s arguable that we are beginning to experience conversations between data sets!

All of this has been a long time coming. The DOI has its roots in the Handle System, whose roots weave back beyond the Web to the Internet Protocol (IP) itself. And back to fiction, as Cheryl Ball notes above, there’s the 1987 digital precursor “Afternoon, A Story” by Michael Joyce (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Afternoon,_a_story).

A long time coming, and to the kids in the backseat reading Pears’s “Arcadia” on their iPads, “No, we’re not there yet … keep reading!”

I should have added the more recent digital precursor “Composition No.1” by Marc Saporta (http://sco.lt/5aHNx3). It is an extraordinary work of “book art” as well as one of experimental fiction published in print and digital form in 2011 by the equally extraordinary publishing house, Visual Editions (http://www.visual-editions.com/ and, more here, http://wp.me/p2AYQg-I1).

I agree that linking is fundamental to the revolution, although i would not call it a conversation. It would be great if there were some way to link to specific sentences or paragraphs. Citing a 30 page article is not useful. Then there is the issue of forward citation, meaning adding citations to new docs as time goes by. This raises the deep issue of the version of record versus the living version, which changes over time. Perhaps we need both, the VOR and the LV. With LVs we could actually have a conversation.

That is what the application of DOIs to standards in the community of publishing international standards (BSI, ASTM, ASME et al.) is laying the ground for. And if you don’t think articles can have conversations, take a leaf from Joe’s book and re-read Jonathan Swift’s “Battle of the Books” for a heated conversation among books 🙂

As a logician I do not find the conversation metaphor appealing. A conversation is a precise logical form, in which specific statements or questions are responded to, by other specific statements or questions, in an ongoing process (thus creating an issue tree). I have taped and mapped many conversations.

If you can explain how articles can have an actual conversation, I would be very interested, but I am skeptical. In the LV case I referred to, the authors would have a conversation, by changing their articles in response to the changes others make, referring to their articles. That static articles can have a conversation I very much doubt. Static article B may well be a response to static article A, but A cannot then respond to B.

Multi-track expository narration is but one of many things that can be done more efficiently and pleasantly in the digital domain. There is so much more to explore, especially with expository non-fiction. I look forward to much more on this subject.

For example, a concept made more understandable via an animation or series of animations. Graphs and charts that respond to a slider linked to a time interval.

True, the eBook, eJournal et. al. is something of a web site in a can but that status may be more important as a VOR than a malleable web page can ever be. This is the case even with versioned eBooks (see Apple iBookstore).

We have only just begun.

I have to agree with what Frank Lowney says: “There is so much more to explore…” I think the author of this post, and many of the commenters, are thinking too small. What novelist Iain Pears has done was already well explored by Michael Joyce and others in the 1980s, and there are precursors not only in the highbrow literature that Joseph Esposito mentions, but also in popular literature such as the Choose Your Own Adventure book series published in the 1980s and 1990s. People have been publishing fiction and nonfiction literature in app form for at least three decades.

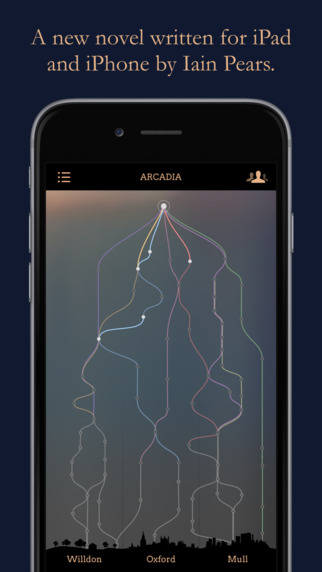

I agree with Frank Lowney that animation and other dynamic visual content (using scripting frameworks such as D3.js or even more complex 3D frameworks), especially based on rich semantic markup and spatio-temporally explicit information from geotemporal databases (geographic information systems such as Google Earth but with a temporal dimension), is an important frontier; the importance of this frontier is implicit in the screen shot of Iain Pears’ novel Arcadia that shows the what appear to be time-paths or world-lines in the style of Torsten Hägerstrand‘s time geography (implemented, in recent years, in software applications such as GeoTime). On the importance of geocoding scientific and scholarly work, see, for example, Nigel Pitman’s 2011 editorial How ‘geotags’ could track developing world science.

Dynamic graphical representation of the argumentation in nonfiction is also an important frontier, as suggested, for example, by Robert E. Horn‘s information mapping and by data standards in argument mapping such as Argument Markup Language (AML). See, for example, the 2013 article by Floris Bex and colleagues on implementing the argument web.

I’m reminded of what Michael Miner wrote a few years ago in a brief article in the Chicago Reader titled (in the print edition) Narrative nonfiction: essential or overrated?: “Writers of a certain age who grew up on Talese and Didion (Gellhorn, who covered the Spanish Civil War, requires a longer memory) esteem narrative nonfiction—but do readers? Perhaps some readers don’t trust a gripping narrative because they don’t like to be gripped. They’d rather be free to assemble the truth from found objects of their choosing. The Internet has made this kind of do-it-yourself journalism quick and simple; even old-school journalists might admit it’s easier to object to philosophically than to resist. But those philosophical objections stand on shaky ground.”

I don’t think people are thinking small. The kinds of things you and Frank are pointing to are major productions, by experts. Journal articles are simple notices of findings, by researchers. The two media are just very different.

David, I don’t disagree with anything you’ve said above; in fact, I think your comments above were insightful, and some of what I wrote (about information mapping and argument mapping) was just a repetition of themes that you raised earlier. (In fact I was so impressed by what you wrote that I emailed you privately as well—if you didn’t receive my email, let me know.) My comment about “thinking small” was pointing in the same direction as Frank: toward the immense unexplored possibilities of digital media for scientific and scholarly publishing. I disagree, though, with your statement that the “kinds of things you and Frank are pointing to are major productions, by experts.” I am not an expert in any of this, but I am personally interested in using the tools that I mentioned. How widespread their usage becomes may depend on how accessible the software becomes. At the moment I don’t see any end to my habit of “squirreling away” PDFs, as Charlie put it above. I agree with what avant-garde composer John Cage once said in response to the question “Would it be good if the sounds of life eventually replaced the concert hall altogether?” Cage replied: “Not altogether. In the future, it seems to me, we should want all the things we’ve had in the past, plus a lot of things we haven’t had yet.”

On the vision side, Nathan, I think issue trees visualizing the knowledge and reasoning going on in specific scientific research areas would be very useful, but definitely a major production. The tree would grow and change with each new paper. (I have not received your email. dwojick@craigellachie.us)

I agree: Imagine if the major journal publishers encouraged (or even required) article authors to submit a structured argument map of the arguments in each article submitted. The publishers could provide an easy-to-use web-based system (based on software created by argumentation experts) that authors would use to create and submit each argument map. The system would automatically transform the map into some kind of standard data format such as Argument Markup Language (AML). This data could be made available both to end users of individual articles (in the form of raw data and/or an interactive visualization) and to authorized web spiders that would aggregate and analyze the data, in the same way that journal publishers currently make articles available to Google Scholar’s web spiders for indexing. I have not read that such a system is currently in preparation, but it is technically feasible and I can’t be the first person to have thought of it. (As I noted above, I think that it is equally important, or even more important, that journal publishers collect and make available geotemporal metadata for all articles. This is especially crucial for all research involving fieldwork. Just like the argumentation data previously described, the geotemporal metadata could be visualized by end users of individual articles, and aggregated and analyzed by web spiders for article indexes.)

Once again I disagree. Getting published is already too burdensome. If argument mapping is worthwhile it should be funded, not mandated. It does look interesting, however. Given that the argument maps are also tree structures, the mapping community might find issue trees useful, because they are already there in the writing. But argument maps are vague compared to issue trees.