Mark Zuckerberg is doing an interesting dance these days. He is facing criticism that Facebook’s promotion of “fake news” may have influenced an election.

Mark Zuckerberg is doing an interesting dance these days. He is facing criticism that Facebook’s promotion of “fake news” may have influenced an election.

Zuckerberg thinks this is all hogwash. He posits that Facebook users cannot be influenced by “fake news” on Facebook in their election decisions and further contends that fake news is not very prevalent on Facebook, despite evidence that seems to say otherwise. David Crotty did a nice overview of this earlier in the week.

As someone who uses Facebook to access news by following many different mainstream news outlets, I can say that almost any click on a Washington Post or New York Times article will result in the delivery of “recommended for you” articles from fake news sites and conspiracy theory pages.

Facebook’s fake news problems started before election day when it replaced human curation of their “trending” news list with an algorithm. People had complained that the trending story selections were biased. Personally, I find that most of the time the trending stories are about what happened on Keeping Up with the Kardashians or include “news” about celebrities I have never heard of. So Facebook did the easy thing and removed humans from the process. Enter fake news.

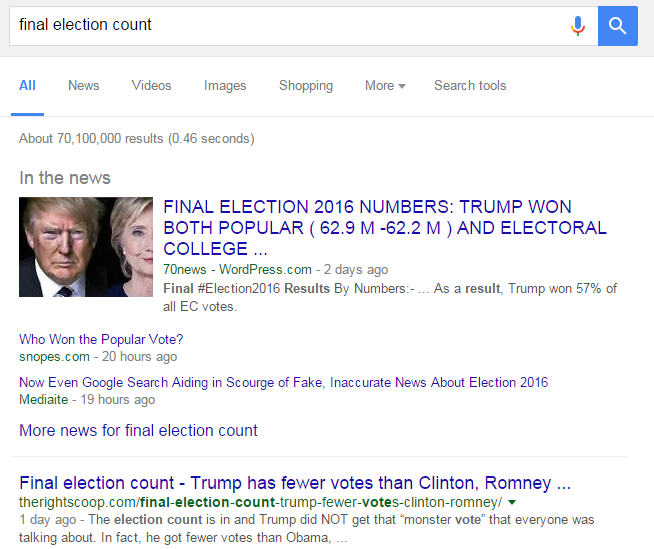

The first logical question for Zuckerberg would seem to be how he can claim that fake news is not “trending” when fake news was doing exactly that based on their algorithm for usage. Fake news became such an internet issue that Google added a fact-checker function in the Google News results. It doesn’t always work. As of 11 a.m. on Monday, November 14, 2016, Googling “Final Election Count” gets you this:

The top result is complete fake. The third result is about the first being completely fake.

I’ve written before about the blurring of the lines on online platforms. When you hear someone make a dubious claim, about anything, and you ask where they heard that, they will often say “It was on Facebook” or “on Twitter”. The original source is lost. Facebook is not creating content, Facebook is distributing content. No one knows (or even cares) who created the content anymore.

Sue Halpern wrote about this over the weekend:

“While it is true that this can be confusing to some readers, who are led to believe that the sites they rely on for information are honest and objective when, instead, they are designed to throw poisonous content into the news cycle, the actual effect is even more insidious: it has created an equivalence between those ideological sites and traditional journalism. In the Internet world, there is no difference between The New York Times and Breitbart.”

Fake news is becoming (or even already is) indistinguishable from real news for many people. Real news is competing with fake news and it’s not going well for them. Trust in journalism has taken a major hit. Further, journalists being able to share minute facts or hunches on Twitter circumvents the role of the editor. It also turns “journalists” into opinion sharers, blurring the lines for readers again. It is difficult to distinguish between fact and opinion among the press corps today.

The dumping of unfiltered and likely altered information from Wikileaks has also corrupted the news, real and fake. News organizations of all shades trolled through emails hacked by Russia and delivered by Wikileaks to find wrong-doing on the part of Hillary Clinton. Much of the “news” that came out of this was completely out of context and old. Some of the information also seems to have been deliberately altered, either by the hackers or Wikileaks.

It seems pretty clear that anyone who thinks “fake” news is not harming “real” news is sadly misinformed. Part of the problem is that newspapers gave away content in the digital revolution. Gave it all away. Now, no one wants to pay for it and an entire generation of “digital borns” never had to. The result is the shutting of papers and dwindling news staff.

Indulge me while I start to weave in some thoughts on how this related to scholarly publishing.

Predatory journals are not exactly the same as fake news organizations but they certainly are publishing papers of dubious quality. Some real journals are being hijacked and turned into fake journals. Finding these papers is not difficult.

Much in the same way that fake news is easily discoverable on Twitter and Facebook, fake journals and their contents are delivered via Google Scholar search. The question that often comes up is, what harm are predatory or fake open access (OA) journals having on real OA journals?

In every discussion I have seen on predatory journals, someone comes forth and declares that these are not a huge problem because real researchers are not being duped and no one would bother to read or use these papers.

Let me explain why this is short-sighted. In a meeting last weekend with 29 engineer editors, three told me in separate conversations that they have had a paper they published stolen by others who stripped the original author names off the paper, put their own on, and paid to publish them in an OA journal. Anyone within earshot of these stories was either shocked, or knew someone who had suffered a similar theft.

Over the course of a year, I get the chance to meet with about 100 editors and associate editors across our journals. The complaints about OA journals is one constant from these meetings.

A familiar complaint is about mass emails sent to presenters from one of ASCE’s conferences seeking solicitations for a Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, which is not the ASCE journal of the same title. Each year I get confused recipients contacting me. Some are concerned with the overlap, others are angry that we would ask proceedings authors to pay to publish the paper in our journal, which we, of course, are not doing.

The editors’ always complain about the massive amount of emails they get from OA journals. Some have been added to editorial boards of these journals without their permission and they can’t find anyone to take them off.

These experiences shape the discussions around openness and access. The editors don’t trust it. They feel a pay-to-publish model is dangerous.

I tell them that not all OA journals are like this. I tell them that some of the things they find in OA journals could happen at non-OA journals; but what they believe is what they see in their inbox or their Google Scholar results.

So is all hope lost when it comes to the reputation of journals in general? Are we destined to suffer some of the same issues facing news organizations today? Yes and no.

For one, scholarly publishers did not choose to give digital content away when journals started going online. It was heavily discounted from print, but there was a cost. Even OA journals, many of which charge an article processing charge (APC), are functioning on an income model. Payment for content supports the idea that “that which has value, costs money” and offers an alternative to the “you get what you pay for” attitude that comes with free content.

Another advantage for scholarly publishing is that the core users of content (researchers) do make value judgments based on the source. The first hallmark of quality will be the author names and if unfamiliar to a reader, the second will be the journal title. The third would be the research institutions affiliated with the authors. If all of those are unknown, a reader is wise to be skeptical.

There are many in the sciences who believe that the great take-away from OA and federal public access programs is providing access to the masses. This is not an uncontroversial idea. I have seen some pretty nasty arguments back and forth about whether the “general public” has a need or use for scholarly papers. Regardless, they do have access to OA content and have access to federally funded works and preprints now and even more in the future.

As the general public is being introduced to more and more scholarship, it seems even more important to be concerned about the bad actors. We have already seen skepticism of the entire scholarly publishing process in mainstream media. How do we also expect the public to differentiate a “fake” or “predatory” journal from the ones that perform due diligence? If you are expecting the dad researching a child’s condition or a daughter looking for new treatment outcomes for her mother’s illness to sort through the DOAJ list to see if what they found is from a reputable source, then your expectations are unrealistic.

The general public is also learning about scientific discovery through the mainstream media, which have been cutting their science and health reporting staff for years. Will the general assignments reporter know the difference between a reputable journal and one that offers no validation of any kind?

The cable news networks and national news organizations are doing some major soul searching this week. They are in the position of having to convince users that they should pay for content. This is a tough sell when the person who won the election campaigned partly on the deficiencies of the media.

Further, Facebook is having to defend itself again on whether it’s a social network or media platform. Scholarly publishing and the networks that feed into it and off of it would be wise to take a few steps back and think about any lessons learned that may apply to us. Martin Baron, Executive Editor of the Washington Post, had this thought on the topic:

“People will ultimately gravitate toward sources of information that are truly reliable, and have an allegiance to telling the truth. People will pay for that because they’ll realize they’ll need to have that in our society.”

I guess time will tell if he is correct about that.

Discussion

14 Thoughts on "What We Can Learn from Fake News"

[Zuckerberg] posits that Facebook users cannot be influenced by “fake news” on Facebook in their election decisions and further contends that fake news is not very prevalent on Facebook.

I’m struck by the parallel to arguments that we often hear from OA advocates who don’t want us to talk or worry about predatory publishing.

The so-called “predatory journal” situation is complex and poorly understood. On one hand there are some truly predatory journals, which may or may not be a significant problem. But then too there is an explosion of low cost OA journals, which may or may not be legitimate; we do not know. (I begin to address this issue here: http://davidwojick.blogspot.com/2016/09/predatory-versus-low-cost.html, based on amazing data from Shen & Bjork: http://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-015-0469-2).

If the growth rate documented by S&B continues, the number of articles published by low cost OA journals might approach the number published by all of the conventional journals, OA and subscription combined. Is this good or bad? I think we do not know.

Undoubtedly bad. Small dollops of droppings spread in a large field can act as fertilizer, a large mountain of said droppings is a health hazard…

Ironically enough, the alarmist rhetoric of “predatory journals” originates from the same source as the fake news story featured in Angela’s screenshot — a wordpress.com blog. It wouldn’t be surprising if that whole controversy were a tad overblown as you suggest.

Further reading…

The piece “In the Wake of Digital Tribalism, Institutions Are More and More Useless —

Online media is accelerating our own pitfalls” by Michael Marinaccio offers food for thought on what could happen if content on social media is read exclusively by like-minded individuals – tribes as it were – becomes the new normal.

https://the-politic.com/digital-tribalism-6caf30cf0484#.f5inosi5h

Well, it looks like we’ve already arrived at point. Let’s hope someone threw down some bread crumbs so we can find our way back.

Thank you, thank you for pointing out the real victims of predatory publications are not just the authors who naively pay for sham reviews! The real victim is truth itself. Outside of the professional research community, all journals look alike. A few organizations like ASCE may have the brand recognition to gain trust, but most of us are competing with the phonies. This is a truly frightening situation for a society that depends upon reliable information.

Years ago, our little journal went with a major publisher because they offered wide distribution (quite successfully). If we were to redo the competitive process today, we would weigh more heavily the strength of brand reputation. I would want people to see that publisher’s name and know our journal is legitimate.

There’s a lot of information on the internet; some of it’s even true.

I have two suggestions for the problems mentioned here. (1) For Facebook I recommend that everyone include people among their “friends” who are not in the same ideological camp, so that whenever you are tempted to believe something reported in the news that favors your point of view, one or more of these friends will be there to raise questions. (2) For scholarly publications, I recommend that all emails for professors be readily discoverable by searches of their departmental websites, so that anyone interested in finding out the truth can write directly to the author, or to the person who is taken to task in another author’s article or book. Many professors’ emails are discoverable in this way easily, but you would be surprised at how many universities make it difficult to find out what those email addresses are.

Not sure it matters who won the popular vote because neither candidate sought to win the popular vote. Both candidates executed strategies based entirely on the Electoral College system. Neither Trump nor Clinton would have spent so much time in battleground states had the path to the White House been a simple plebiscite. No one can say that Trump could not have carried California or New York, purely because he did not campaign so much there. Had the system been the popular vote, he likely would have campaigned in the most populous states and maybe won anyway. Conjecture about “what if” is pointless after the election. He won. Deal with it.

Thanks for a thoughtful and very timely piece, Angela.

I recently listened to two episodes of This American Life that explored some of the issues you write about above.

Seriously? is about how social media and the alt-right media has created a sort of alternate history where a large number of people believe things that are just not consistent with easily verifiable facts.

https://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/599/seriously

Will I know anyone at this party was more shocking about how this has changed the Republican party in particular beyond recognition.

https://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/600/will-i-know-anyone-at-this-party

Much of this episode is about the GOP itself, but there’s a disturbing moment at 46m20s, when a reporter speaks to a state representative that has been in government for over a decade. He swore blind that Dearborn Michigan has transitioned to Sharia law and acted utterly incredulously to the idea that the reporter did not know this. This was such an extraordinary claim that I decided to track it down. It comes from here:

http://nationalreport.net/city-michigan-first-fully-implement-sharia-law/

What’s amazing about this is there is a link to a disclaimer page that states clearly that the website is ‘fake news’ and ‘satire’. The problem is that it’s not satire. It doesn’t read like the Onion or the Daily Show. As a result the story being widely shared and take as truth by at least one state legislator. It seems that a lie really can spread around the world before the truth has got its boots on. That’s truly frightening.

To channel Robert Harrington, there’s a need for balance. If we do away with quality control and measures of trustworthiness, we risk heading into a dark path indeed, but on the other hand, if we are too precious about new ideas and too closed about how those ideas are communicated, we slow the progress of academia.

Great piece, Angela. I’m sharing it as widely as I can as I think we need to all pull together to spread awareness of the problem and work together to find solutions.

Sandy’s suggestions are very good ones. I would add that we need to make some of the checks and balances that are currently optional into *mandatory* ones in order to guarantee academic legitimacy. This needs to happen at all stages in the publishing process – prior to submission, during peer review and once material has been published.