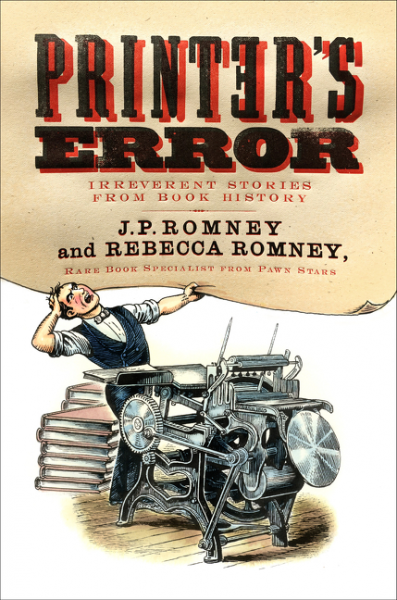

Every now and then a book comes along that reminds you of how delightful our publishing world can be. Printer’s Error: Irreverent Stories From Publishing History, published by Harper Collins in early 2017 is one such book. The authors are Rebecca Romney and J. P. Romney. You may have seen Rebecca before; she has appeared many times on History Channel’s Pawn Stars as a rare book expert. Rebecca is clearly deeply enamored of the book world, especially rare books, and comes to this book having worked with Bauman Rare Books in New York and Philadelphia for many years, and is now installed with Honey & Wax Booksellers in Brooklyn. She speaks a number of languages including English, French and Japanese but, perhaps more intriguingly, reads old English, ancient Greek, and Latin – how often do you meet someone with those skills? Her co-author is also rather interesting, and is both a historical researcher and novelist. Lest you think that somehow, being involved in the world of rare books makes the authors luddites, together Romney and Romney also produce a fascinating podcast called “Biblioclast: Fighting Book Snobbery 10 minutes at a time”, and Rebecca has launched a new blog entitled Aldine, named after Aldus Manutius, the 15th century Venetian printer who supervised the creation of the Italic fount and popularized the octavo format outside of religious works.

The book itself has clearly captured my imagination, perhaps all the more so because of my family background. One of those rare books was written by my ancestor, Sir John Harington. His work, The Metamorphosis of Ajax, was written for Elizabeth I and contained writings and drawings of the Water Closet – yes my family’s words led to the creation of something we all use.

A memorable quote, entirely relevant to discussions we have here at The Scholarly Kitchen is:

“When faced with a flood of information, misinformation, and conflicting sources, how do you know what to trust?”

We are living in an era where words spoken, or written on a page, are no longer trusted sources of fact. Indeed, we have progressed beyond a lack of trust in words to knowing that words are used to intentionally mislead us. It is hard for us to look at the printed word and not to trust it. They are, as the Romneys indicate, “pure and pristine, but like the surface of a quiet lake, underneath those printed words lie murky depths”.

Of course, you may just be looking at an error. One such famous error may be seen in what has become known as the “Sinner Bible”, a 1631 printing of the Bible by Robert Barker, who owned the exclusive privilege to print bibles in London. The story goes that near the end of his career, he failed to proofread closely a run of 1000 copies of the Bible. In this particular printing an important word was omitted: instead of the Ten Commandments stating that “Thou shalt not commit adultery”, his version stated “Thou shall commit adultery”. Needless to say Barker was summoned for punishment by King Charles I over that one.

Not all of the book is dedicated to errors. The authors also tell stories of fabulously meticulous forgeries, such as Marino Massimo De Caro’s forgery of Galileo Galilei’s first telescopic observations of the night sky. It took serious detective work to finally uncover this as a fraud, using clues such as the depth of the pressed type, a faulty capital P, the absence of wax on the binding thread – but it fooled almost everyone for many years.

Most of us think back to the wondrous invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the fifteenth century. But not all was smooth with the introduction of threatening new technology. A Benedictine monk called Johannes Trithemius objected to the whole thing, extolling the virtues of hand-copied manuscripts. In the seventh and eighth chapters of Trithemius’s In Praise of Scribes, he criticizes the new technology of the printing press, extolling the virtues of “Handwriting placed on parchment (animal skin) will be able to last a thousand years. But how long, forsooth, will a printing last, which is dependent on paper?” In other words, paper wasn’t seen to last as long as animal skin – but of course it was much cheaper. I find Romney’s use of this example quite interesting, drawing analogies to how we view the inexorable shift from printed book to ebook. There is the notion that printed books have a permanence that is just not possible with their digital cousins – but of course we have to all realize that we are rooted in what we know and none of this is new. In fact ebooks have given a new lease of life to books – allowing for small devices to hold multiple books, and for consumption of a book in an entirely different way – but yes you will miss the crack of the spine and the smell of the ink and glue.

Another story that is beautifully told, and has significant resonance for our current political conditions, is the story of Mary Wollstonecraft, eighteenth century author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Wollstonecraft was unconventional, unorthodox, and a force for women’s rights. Wollstonecraft ended up marrying a philosopher, William Godwin, despite their shared belief in the tyranny of marriage. Tragically, she died soon after from complications of childbirth. Her husband decided that he wanted to write a memoir – what we now think of as a biography. This was before the notion of ‘biography’ was well-established, though one written about Charles Dickens was published in this same period. Godwin told it all. He regaled the reader with details of Mary Wollstonecraft’s unorthodox personal life and her revolutionary writings. Her critics seized on these words and the public was shocked – her husband had effectively destroyed her reputation, through misunderstanding the impact of the printed word – despite his love for her.

I have given you a taste of a few of the stories that make this lovely book a must-read. Perhaps as a suitable summary of the tone of this book, I will relay one of the Romney’s quotes from Sherlock Holmes:

“There is nothing more deceptive than an obvious fact”

This really does bring home to us the power of the printed word, and its ability to fool us if we are not vigilant – and yet the book lives on.

You should read this book.

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "Book Review: Printer’s Error: Irreverent Stories From Book History"

Thank you for the enticing review, Robert. I’ll add it to my summer reading list!

I’m definitely adding this to my reading list. Thanks for the recommendation, Robert! I’m curious, did you read the print version, or the e-book?

I read the print version – appropriate I would say.

As the owner of first editions of works by both Godwin and Wollstonecraft, I was naturally intrigued by mention of Godwin’s biography of his late wife. Your short review here has already led me to sign up for Romney’s blog.

This is a delightful review, Robert! I look forward to reading this book, and probably giving it to a couple of friends.

I look forward to getting my hands on the book. But, please note you have a printer’s error, or perhaps an author’s error, in the title of Wollstonecraft’s book in this article. It’s “Woman,” not “Women.” According to Encyclopedia Britannica, “Her mature work on woman’s place in society is _A Vindication of the Rights of Woman_ (1792).”