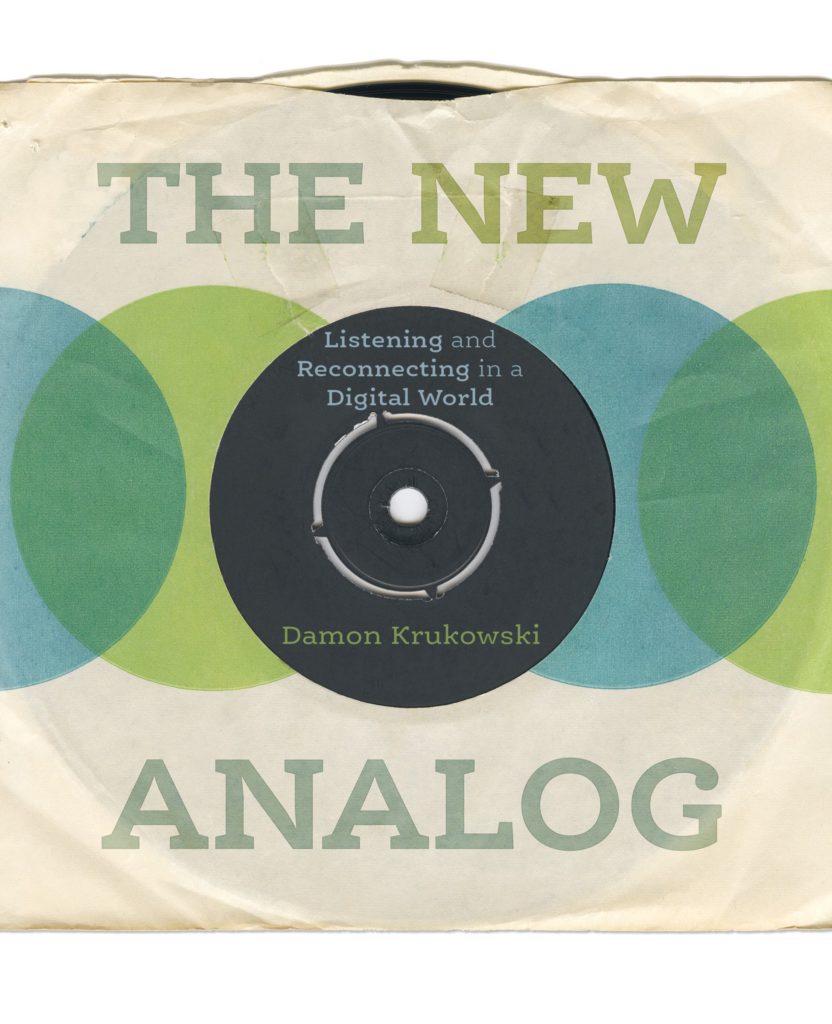

Digital media offers us so many benefits (easy distribution, reach, portability, convenience, cost savings) that we often don’t stop to think about what we’re leaving behind. In The New Analog: Listening and Reconnecting in a Digital World, author and musician Damon Krukowski asks us to consider the difference between analog and digital information and what’s lost when we transition from one to the other. While remaining positive about digital technologies, Krukowski offers useful concepts and food for thought for anyone creating digital media or designing user experience (UX) for digital platforms.

Music fans may know Krukowski as one of the founders of the seminal late 1980s band Galaxie 500, or for his subsequent work as half of Damon & Naomi. Given this background, Krukowski focuses his insightful examinations of media through music, whether the design of the Teatro alla Scalla in Milan, The Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds, or even Kiss’ famous fake wall of Marshall amplifiers. One of the key concepts presented is the balance between “signal” and “noise”:

Noise, to an electrical engineer, is whatever is not regarded as signal. Analog media always includes noise, necessarily — efforts to minimize noise in analog environments adjust its ratio to signal (“signal-to-noise ratio”), but never eliminate it. Digital media, on the other hand, are capable of separating signal from noise absolutely. Given a definition of signal, the digital environment can filter out noise completely; this is fundamental to its efficiency as a medium for communications.

But as Krukowski notes, “noise is as communicative as signal.” The information around what we’re focusing on gives us vital clues about both our environment and context about the signal itself. The microphones used by cell phones for example, while technologically superior to those they replaced, deliberately filter out background noise, and often vocal tone. This makes conversation via cell phone more difficult to interpret than on the analog land lines they replaced. In the book, a woman wearing noise-cancelling headphones falls off her bicycle while riding down the street. She became “aurally disoriented” because a sense we use for localization had been disrupted rather than aided by technology.

“Thick listening” is another key concept for the book, and one that resonates strongly for the world of scholarly communications. Here the idea is that the thick layers of analog tape used to create something like Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band carry much information in the noise that accompanies the signal, enough to give one a sense of place and time, whether through the noises inadvertently captured on tape or even just the background hum of the studio itself.

The art of reading a scientific paper is itself a form of thick listening. Reading between the lines is a necessary skill for getting the most out of an article, as a careful analysis of the words chosen, the references cited, the journal selected for publication all offer important clues about the author’s intentions and the contextual meaning of the research. Journal publishing has removed a lot of that context as we’ve moved online and into an article-level economy. Just as Krukowski laments the loss of liner notes and credits for music, so too have we removed the front and back matter from visibility. Who was the editor that made the decision on this paper? Was a figure from it chosen for the issue’s cover?

At the same time, the digital environment offer us opportunities to provide that context, rather than the automatic stripping away of anything not deemed essential “signal”. Where music has moved toward the smallest file format possible, the mp3, sacrificing depth of sound for convenience and portability, the research world is increasingly thinking about expanding into the broad open spaces offered by discarding the physical limits of the printed page. Making peer reviews available alongside the article, along with datasets and detailed methodologies can offer powerful contextual information, enabling a deeper understanding of the work presented.

The important question then, is who decides what is signal and what is noise? For digital media, that decision must be made at some point in the process, and makes the difference between Frank Sinatra’s subtle microphone technique and the brickwall mastering of Metallica’s much-maligned Death Magnetic. Human beings have evolved superb abilities to detect differences in tone and to effectively sort signal from noise. Yet we seem eager to turn that responsibility over to others:

Facebook sorts those posts using algorithms to determine which it considers signal — bringing those to our attention — and screening out those that are, in its estimation, noise. The result is that we see nothing but signal in our feeds — that is, nothing but signal as determined by Facebook. Even if its algorithms are accurate, Facebook is screening out precisely the kinds of noise we are skilled at sorting ourselves: posts we don’t find especially interesting. But the act of sorting through that noise is itself a tool for communication…Without our own active judgement sorting signal from noise, we lose our social bearings on Facebook as surely as the bicyclist wearing headphones lost her sense of location in the street.

Are we ready to cede our active judgement of the scholarly literature to the likes of Google Scholar and Meta? If so, what context will we lose in the process?

The New Analog is a fun read, full of all sorts of entertaining examples (e.g., how the “Sensurround” of the movie Earthquake really worked) used to stimulate thought on deeper, more troubling concepts. It’s a beautifully-designed physical object, and a perfect gift for both the music lover and the book aficionado in your life. Best of all, as pointed out in the tongue-in-cheek introduction, despite our surveillance society:

The author and publisher of this book do not have any information about you; they do not even know that you have a copy of this book unless they sent it to you personally. And if they did — send it to you personally, that is — you can always pretend to have read the book without having done so. You can also deny having read it, should that prove expedient. It’s your business, really.

Ah the joys of analog books!

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Book Review: “The New Analog” by Damon Krukowski"

Nice review, and it sounds like an interesting book. I was recently in a conversation with someone about the lost element of serendipity in the digital age. Serendipity might also be considered noise — the article you didn’t expect, the research framed in a way that matches an unspoken thought, etc. It would be nice to have more serendipity designed into the signal, as it’s a useful form of noise.

Noise is always in the eyes (and ears) of the beholder. Personally, I prefer to listen to Glenn Gould’s 1981 recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations (often referred to the “sing-along” version where you can hear Gould humming and groaning as he plays, video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aEkXet4WX_c). Recording engineers considered Gould’s vocals as background noise and attempted to remove it. Me? I consider it part of the performance.