Note from Alison Mudditt: In today’s Guest Post, Anthony Cond, Managing Director of Liverpool University Press, provides an overview of last week’s University Press Redux conference, following up on the highly successful inaugural meeting in Liverpool two years ago. In my review of that meeting, I noted that university presses “need to demonstrate the value we bring to our institutions and wider stakeholders in increasingly concrete ways”, and so it was interesting to see that theme front and center at last week’s meeting. Many speakers tied the surge of interest in university presses to their potential to concretely showcase their institution’s scholarly impact on a global level. Read on to learn more about the very different ways in which presses are fulfilling that mission.

The world’s first university press received its charter to publish in 1534, facilitating the suppression of heretical treatises and notably freeing the University of Cambridge from the exclusive licenses and high prices of the London stationers. In 1696, after years of erratic publishing with the external partnerships of ‘three stationers and printers, or sellers of books . . . to print all manner of books approved of by the Chancellor or his vicegerent and three doctors,’ the first attempt was made to bring the press under the direct control of the University. The world’s first full-time university press director Cornelius Crownfield (‘a Dutchman . . . and a very ingenious man’) was appointed and a body of Curators (later Syndics), statements of work, rules for business conduct, and records of sales were instituted, with most books printed to the order of the author or booksellers. It took one hundred and sixty-two years for the University of Cambridge to figure out a structure and a strategy for its press. It has fared rather well since then.

Those same questions of university/press organization, structure and strategy underpinned much of the discussion at last week’s University Press Redux Conference, hosted by ALPSP and brilliantly curated by Lara Speicher at UCL Press. Whereas the conference’s previous iteration focused on the Janus-like nature of the university press, at once grappling with a still successful print heritage and the opportunities of a digital future, the event at the British Library — with university presses from more than a dozen countries – showed that despite a plurality of business models, shapes, and sizes, the common thread among university presses remains the institutional relationship and mission.

Pronouncements on university presses have too often treated the sector as homogenous. In an event that was notable for its free-flowing discussion and collegiality, the concept of success for a press as articulated at Redux took many forms, ranging from global sales to open access (OA) downloads, university service to innovation, reputational enhancement to collaboration. Individual press achievement could ultimately be judged against only one set of criteria: the criteria for success set out by the press’s home institution. In this range of diverse experiences there was much for all presses to learn.

Take Goldsmiths Press, founded less than two years ago with a remit to be ‘SFG’ defined for the uninitiated as ‘Someone who attends Goldsmiths University and acts and dresses in a particularly “cool”, arty or “individual” way typical of the University’s reputation.’ The new press has been conceived to live and breathe Goldsmiths: its books look a certain way and read a certain way, commencing with Les Back’s Academic Diary: Or Why Higher Education Still Matters. In fact, as conference delegates will attest, the Press director Sarah Kember even presents the Goldsmiths’ way: there is no mistaking from whence that imprint came. If Goldsmiths’ criteria is brand extension, its press is off to a flying start.

Longer established presses have this down too. Amy Brand’s keynote highlighted that MIT’s values are visible in more than just its Press’s iconic, Muriel Cooper-designed colophon — a Publishing Futures Lab, MITXP tying Press and university together for online learning, graphic art treatments of topics ranging from the nature of the universe to women in science, projects to unlock deep backlist with the Internet Archive and to establish a visual identifier for peer review of scholarly books — all sit alongside elegant print products and aspirations for the cutting edge of digital. This isn’t just the work of a generic university press, it is a list of initiatives in which university, press and external audience can all see shared MIT values and ambition.

That question of institutional relationship may have a whole new sense of urgency for some presses depending on how the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE), and its successor Research England, unpacks a key announcement made at the conference. Actually, “announcement” is overstating it: it was more an expansion of an earlier hint on page 36 (Annex C) of December 2016’s Second Consultation on the Second Research Excellence Framework, that to be eligible for the next but one Research Excellence Framework (REF), which feeds the distribution of £1.6 billion of annual quality-related university funding in the UK, all monographs will need to be available in an OA manner. That is, in just over 1000 days from now in January 2021, when the REF 2027 cycle starts, UK university academic book authors will be expected to meet some as yet unspecified OA requirements. Only time will tell the exact form of OA that will be prescribed – Annex C somewhat frustratingly states ‘We do not intend to set out any detailed open-access policy requirements for monographs in a future REF exercise in this annex,’ and there hasn’t been a great deal of public discussion with publishers since its publication, at least until HEFCE’s Head of Research Policy, Steven Hill, threw down the gauntlet at Redux. Meanwhile, the 19 ‘new university presses’ in the UK and 12 institutions considering following suit according to JISC’s Graham Stone, look distinctly like a hedge on the long-term future of scholarly communication, and those US university presses that have been reluctant to engage with OA may feel obliged to do so or risk losing UK authors.

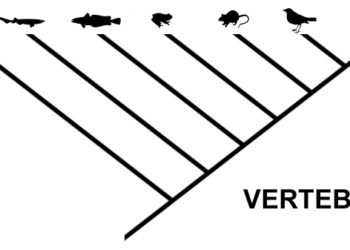

Regardless of whether you publish in or from the UK, the recurrent theme of institutional alignment in university presses has never been more important. It seems absurd to suggest that a press might adjudge its raison d’être to be one thing and a President/Vice-Chancellor to think it another, or worse still not to realize it has one at all. If you are a Press director reading this, can you honestly say that the head of your institution knows your press’s strengths? And of course, those should be communicated in big picture terms for your university: an outstanding subject list is understood by a discipline but university managers need to understand the place and importance of the press in the wider institutional ecosystem. As University of Georgia Press’s Lisa Bayer observed in her splendid Taxonomy of Relationships between American University Presses ‘we all know that politics are no longer “as usual” in any sense; and no press director can afford to take support and, realistically, mere existence, for granted.’

(The extraordinary tweeting of Alastair Horne @pressfuturist provides summaries of day one https://storify.com/ALPSP/redux18-day-one and day two https://storify.com/ALPSP/university-press-redux-conference-day-2 of the conference. The next University Press Redux will be curated, appropriately enough, by Cambridge University Press in 2020.)

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Guest Post: Institutional Alignment: The University Press Redux"

To respond to the question about whether the president of the university knows that the press’s strengths are, I’d warrant that university press directors in the US know how important it is to have support at the top and make sure that the answer to this question is yes. In my case, when i was hired as director at Penn State, Bryce Jordan as then president wanted the press to help build the university’s reputation in the liberal arts to better complement its strengths in the STEM fields, and that is exactly what we did. From having won just four book awards in its previous thirty years in existence, we went to having over 100 such awards by the time I retired twenty years later. Those awards helped departments attract new faculty, we were told. We also made it our mission, as part of a state-funded university, to publish a first-rate list of regional titles. And we also provided opprtunities for undergraduates to be interns at the press, a mission we felt important enough to include in our mission statement. In 2005 we went further is establishing jointly with the library the Office of Digital scholarly Publishing, which led to the administrative merger of the press and library. As any press director knows, having that relationship provided a kind of extra political protection from threats of closure: there is no better ally on campus to ward off such threats than the head librarian! (We also worked closely with football coach Joe Paterno, who with his wife Sue was a major fund-raiser for the library. If JoePa was on your side also, no one at Penn State, including the president, could touch you!)

Alas, Sandy, it also seems that if Joe Paterno was on your side, you could touch plenty of minor children. I was with you until that last highly unfortunate parenthetical statement.