Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Gwen Evans, Executive Director of OhioLINK.

OhioLINK, the state agency for Ohio’s higher education libraries, recently negotiated statewide pricing agreementsfor inclusive access textbooks with six major publishers: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., McGraw-Hill Education, Pearson, Macmillan Learning, Cengageand Sage. It covers all 91 member institutions in OhioLINK – public and private. According to the publishers, this is a groundbreaking initiative in its scale and comprehensiveness across virtually all non-profit higher education institutions in a single state.

OhioLINK is passionately pursuing a multi-pronged, hybrid approach to textbook affordability. Not just OER (Open Educational Resources), not just library materials, and not just inclusive access. Why? Because our sole interest in these efforts is the benefit of students, which requires us to evaluate strategies based on their potential for impact—both immediately and in the future.

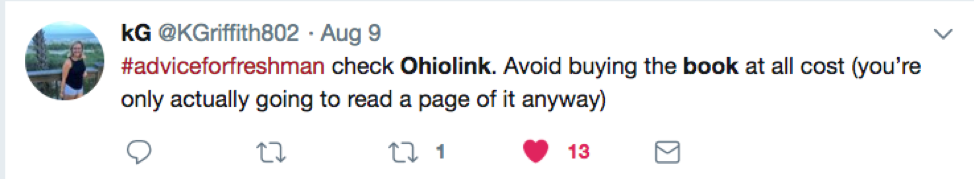

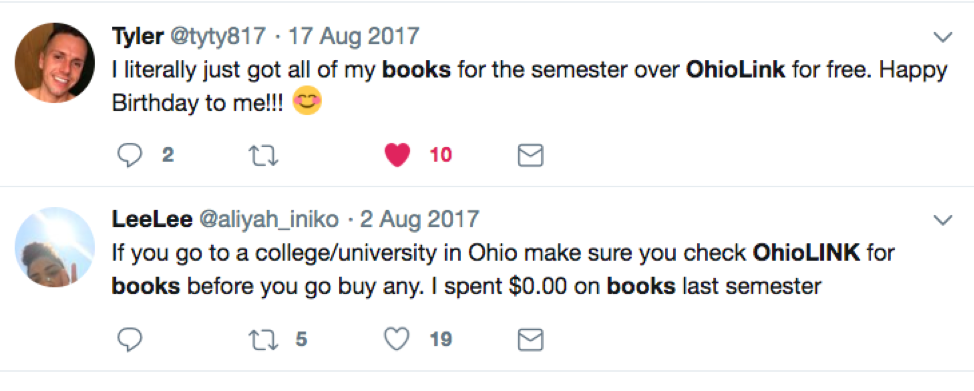

As all library consortia that participate in print sharing are aware, libraries are often credited with supplying textbooks for students, even though almost no member libraries acquire textbooks qua textbooks at scale (and if they do, they almost never lend them via Interlibrary loan or other methods of print resource sharing). When students refer to “getting textbooks from libraries,” they usually mean scholarly or trade monographs that happen to be course adopted, not the titles that are typically assigned in an introductory general education class.

OhioLINK does have a very deep collection of ebooks, databases, digital multimedia, and ejournals that are shared among all our members and are critical components in licensed library resource focused efforts like Ohio University’s Alt-Textbook program. Beyond this traditional approach to supplying affordable learning materials, OhioLINK is also a member of the Ohio Open Ed Collaborative, providing major support for a $1.3 million OER grant from our parent agency, the Ohio Department of Higher Education. We joined the Open Textbook Network(OTN), and support a team of OTN-trained OhioLINK Affordable Learning Ambassadorsthat give workshops and promote OER and other affordable textbook strategies on our member campuses.

However, as student costs soar and textbook affordability becomes a growing issue across campuses, OhioLINK has used the traditional strengths of a library consortium to address the pricing for commercial textbooks at the statewide level. We chose not to make our focus on OER efforts exclusive. Instead we branded our efforts as Affordable Learning Ohioto encompass OER, use of library materials as textbook replacements, andother strategic efforts designed to bring commercial textbook pricing down.

Why OhioLINK promotes a varied approach to textbook affordability

OhioLINK settled on targeting the “inclusive access” or “first day”model for commercial textbooks. While these price agreements have been received with great enthusiasm by our membership, there has also been some pushback. Many OER advocates, including many librarians, believe that any attempt to negotiate with traditional textbook publishers will impede OER and open education efforts, and that success with OER requires refraining entirely from engagement with commercial publishers at any cost – even if those costs hit the very students we are trying to help. We decided on a more practical solution, one that would provide tangible benefits to students immediately.

We’ve fielded numerous questions — and some challenges — from the library and Open Educational Resource (OER) communities, ranging from misunderstanding of what OhioLINK actually did, to fear that efforts like these will undercut OER adoption and promotion and put students and institutions under thrall to commercial publishers yet again. Commenters on Twitter likened the agreements to another “Big Deal” that would lock in participants to specific content, misunderstanding the purely optional nature of inclusive access for institutions and that no content was actually being acquired (except by students in an alternative billing and delivery model to their other personal acquisition models). Others misconstrued the billing to the student’s bursar account as an instance of forcing students to use “the company store,” unaware of the federal opt out requirement, calling the model “heinous.” Our OER partners in various initiatives expressed anxiety that inclusive access deals meant that our very material support for OER initiatives would somehow be lessened, or implying that the promotion of cost-cutting measures that benefited commercial publishers in any way was suspect.

At OhioLINK, we do not view inclusive access as a threat to OER. In fact, we do not view any one affordable learning strategy as a detriment to another.

OhioLINK recently held a statewide Affordable Learning summitwith more than 100 attendees from 40 institutions. There were several panels with faculty who had adopted, were adopting, or were identifying/creating OER either as part of the Ohio Open Ed Collaborative or independently at their institutions. What struck me during the summit was how iterative and partial the adoption of OER was, even by these highly committed, very engaged, very knowledgeable faculty members. The faculty had to revise their teaching and restructure their classes to accommodate the switch to OER materials. The adoption journeys included a faculty member adopting OpenStax textbooks in two classes, but having a third one where OER was not a good fit, leaving him to revert to another text for a couple of semesters while he aggregated some additional OER sources. He still uses commercial courseware, and he commented that “at least they are only paying $35 for the courseware, instead of $35 plus $200 for a textbook.” Another faculty member suggested testing the waters by incorporating parallel resources – assign the current commercial text alongside a comparable OER textbook and “see how it goes,” thus involving the students in the incorporation and assessment of two competing resources while providing a free option if students needed one. In a couple of semesters, the OER materials could become the primary materials by a more gradual incorporation and revision of the syllabus. Another pair of faculty who wrote an OER textbook that will be adopted across multiple sections described the lengthy and somewhat arduous process of involving many adjunct instructors, who are not compensated for such service activities and often struggle to find time, despite a real interest in the goals of open education and OER, especially goals that go beyond simple affordability issues. The Ohio Open Ed Collaborativeare finding that the process of faculty recruitment, identification, and review can be lengthier than expected, even with excellent project support and many willing and knowledgeable participants.

In short, we learned that OER adoption can’t happen overnight, even at the individual faculty level. At the institutional level it’s difficult to scale without enormous administrative support; and it may never completely fill the needs of every instructor and every course. Faculty across our member campuses are also very sensitive to the issues of academic freedom when it comes to choosing content, and initiatives that emphasize the widest possible scope of options while still lowering costs for students have been the most well received. The Ohio Faculty Council, representing all of the state’s public institutions of higher education, adopted a resolution in 2018specifically naming inclusive access as an encouraged and supported approach to lowering textbook costs.

Negotiating lower textbook costs for entire catalogs of textbooks at the statewide level helps students immediately and at a scale that is unachievable with traditional OER adoption efforts. It lowers costs for students in classes where instructors are committed to OER but find they need supplemental material. It lowers costs for students nowwhile institutions gear up to implement OER adoption or creation at scale in the future. It lowers costs for students in courses where faculty are unable or unwilling to switch course materials, but are willing to have their institutions provide an alternative delivery and billing mechanism if digital materials are suitable for that particular course.

One of the most persistent myths we encountered among proponents of exclusively open solutions was that inclusive access locks students in to using the textbook in a particular model with a required charge – we have seen this arrangement referred to as “the company store.” But this is not true; in fact, Federal law requires that s tudents be able to opt-out of inclusive access and that institutions clearly communicate that option, giving them the choice to obtain the textbook elsewhere and in a different format if they prefer. Other commentators have confused inclusive access platforms with courseware. Courseware is computer software, usually with the textbook embedded, that auto-grades homework, quizzes, and may have a variety of learning analytics and personalized tools for both students and faculty built in. If a faculty member requires courseware (as is quite common in quantitative and STEM courses), then students truly have no option but to buy it, because their grades are generated within the courseware. Without an individual negotiation with the faculty member or institution, there is no general opt-out available to every student. But this has absolutely nothing to do with inclusive access. We did negotiate a discount for courseware in the inclusive access model (which means that it gets billed through the bursar instead of students paying for it individually), but the two programs are separate. A faculty member requiring courseware is actually imposing greater restrictions on students. Those restrictions are not usually an institutional decision, but are a property of faculty choice.

We are all playing the long game in textbook affordability whether we like it or not, so how do we proceed in a way with both the long AND short term in mind?

The next post describes how OhioLINK approached commercial textbook affordability, and some lessons learned if other consortia or individual libraries are contemplating stepping into this space.

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "Affordable Learning Requires a Diverse Approach, Part 1: Playing the Short Game (and the Long One) to Secure Savings for Students"

I wonder if Budweiser will follow suit!

College Students Buy a Lot of Alcohol. Estimates vary for how much the average college student spends on alcohol. The most agreed-upon figure available is that college students spend $5.5 billion on alcohol every year. Some estimate that yields about $50 a month, or up to $600 a year per student.Mar 23, 2015

How Much are College Students Really Spending on Alcohol?

https://www.banyanpompano.com/…/college-binge-drinking-alcohol-abuse-florida-alco

On the other hand, Open access and used books….

That allowed students to spend as little as $31 per course on materials, compared to a national average of $153 per course, according to the study. Over the course of a year, the average college student spends more than $1,200 on books and materials, according to the College Board.Jan 26, 2018

What’s behind the soaring cost of college textbooks – CBS News

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/whats-behind-the-soaring-cost-of-college-textbooks/

The difference between the former and the latter is that the former just goes down the toilet while the latter may actually lead to learning something.

Yes, Harvey

The issue here is perceived value- drug of choice. Where there are also many options to gain knowledge, perhaps the price/value of the assigned texts may not be acceptable unless, as mentioned, the text contains a test or other demonstration required to pass the course, the objective of signing up for credit and, perhaps, knowledge. It’s the same for academic publishing (or perishing).

Tom:

What is the value of reading Chaucer or The Molecular Biology of the Cell? I think you are providing a false analogy.

Congratulations to OhioLink for the initiative.

While textbooks represent an expense, because they are separate, often with an “opt out”, they are often seen like the options one has when buying a new car and thus a separate cost decision. What is not considered, and is now coming to the fore is the major cost, the tuition. The article makes an interesting observation that much of this electronic “text” has an evaluative component that has a determining factor in the grades which changes the relationship between the student and provider of the “car”, or in this case, the course. This brings forward the issue of the discounted service of the adjuncts or the entire package, full time faculty, part time faculty, and increasingly intelligent software. And academics thought that their function could not be replaced by AGI or its precursor.

Thus, there is now, within US public hei’s from 2-4 years, the seeking and implementing of a path to lower and even zero tuition. In fact, there are now programs that can offer a 4 year degree at the cost close to what it costs in a traditional institution for one or two semesters, making the cost of supplemental materials moot.

In fact, the OhioLink agreement may be a saving grace for textbook publishers, and, as some of the fear expressed in this piece, may prove problematic for OER in the long run unless these materials tie the faculty to the course as materials become specialized. This points out that many of these materials currently are aimed at the traditional 1st two years which are now easily transferable across institutions, as are, as in Europe, across the upper division.

I have been following the work OhioLINK project with interest not least in that I firmly and passionately believe in the validity the main tenet of the argument “that librarians can play a large role in negotiating arrangements with the large college publishers”

This has benefits for the library but more importantly for our students and our teaching faculty. This has driven the work at a number of UK university libraries where these negotiations and subsequent supply have taken place in recent years. Indeed at my institution, the University of Manchester, we have recently expanded provision by proving the concept to University leadership and subsequently leveraging additional funding

This is not to say that Open textbooks and wider OER provision does not have a potential important role to play or indeed that it has many merits, but it is not there yet on a number of levels and we need to deal with the here and now, where both the demand for textbooks from our students is great and the pedagogical options digital textbooks offer can act as tangible symbol of our central role in teaching & learning at our institutions.

I look forward to seeing and reading about further developments from our American cousins in this area. I believe that the more libraries engage directly in this area the more we will be able to both leverage price and product discussions. These negotiations are not always easy and both publishers and libraries are on a journey, which will have many bumps on the road, but the needs of our students must always come first.

Is the cost of books really a problem? It seems to me that the real problem when it comes to costs in the US are facilities, salaries – especially academic administrators and professors – and amenities to attract students. According to the College Board, the average cost of tuition and fees for the 2017–2018 school year was $34,740 at private colleges, $9,970 for state residents at public colleges, and $25,620 for out-of-state residents attending public universities.

What’s the Price Tag for a College Education? – COLLEGEdata – Pay …

https://www.collegedata.com/cs/content/content_payarticle_tmpl.jhtml?articleId=10064

On top of the above one adds an initial $1200 if one buys all new books (which will be sold back to the book store) which no one does so I would estimate the cost of books around $900 for the year (used books) if one buys all the books assigned which no one does!

So what we will do to provide a solution to an imaginary problem is hire more administrators to negotiate and to administer contracts with publishers which will force an increase in the cost of tuition or fees. After all one has to pay for the savings! While what we probably should be doing is analyzing whether or not we need all those deans!

Wrong again, Harvey. No one was hired to implement this program. The start-up costs go away, and students save money for years. And they also have access to their books after they graduate. As for your point that textbook prices are not a problem, I know few students who would agree with you. Your other point–that costs beyond textbooks are a bigger problem–is valid, but you have not explained why saving in one area should prevent saving in another. Dollars are fungible.