Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Simon Holt. Simon is Publisher, Micro/Nanotechnologies and Reference Content Volume Strategy at Elsevier. He is a member of the Scholarly Kitchen Cabinet, the group that oversees this blog for the Society for Scholarly Publishing (SSP) and the SSP’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Committee. He was recently named a winner of the SSP’s 2020 Emerging Leader Award. The views expressed in this article are his own and are not necessarily those of Elsevier.

As book publishers, a critical part of our job is to understand how and why readers are using our content. The internet means that there is a great deal more content readily accessible than ever before. The quantity of research available at the click of a button nowadays can feel overwhelming – a quick look on the Scopus database, for example, reveals that, since 2016, 1,448,602 articles have been indexed on nanoscience and technology alone. In a world where we are all constantly interconnecting, interacting, and digesting content via mobile technology, social media, and the 24-hour news cycle, it seems we all have more content to digest, and less time to digest it. So, where does this leave what we publish — long-form, reflective content – i.e. books?

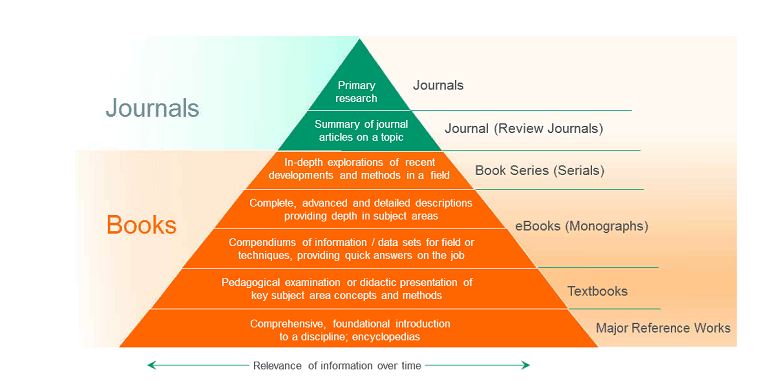

This post looks specifically at the role of book content in the Science, Technical and Medical (STM) researcher ecosystem. It is important at the outset to note the difference in the role of books in STM compared with Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS). A recent joint Cambridge University Press/Oxford University Press report on HSS monograph publishing concluded that ‘Monographs are the established medium for dissemination and debate of new research in HSS’. By contrast, books in an STM context provide reference content; synthesizing and building upon the research in journals to give readers the vetted, established fundamentals of a topic. This gives them the knowledge base they need to then be able to read more granular, focused journal articles with confidence. The infographic below summarises this researcher journey, starting at the bottom and working upwards.

In order to better understand how book content can help researchers, since 2017, Elsevier commissioning staff have undertaken a program of structured one-hour face-to-face interviews with researchers working in the Life Sciences, Physical Sciences, Social Sciences, and Medicine from a diverse range of countries. We ask these researchers what they feel the key drivers are in their fields, what tools and resources they use to navigate the research landscape, and what role long-form reference content (book content) plays in helping them solve research problems. We have interviewed over 400 people to date and, since 2018, we have also captured responses from over 1,000 book proposal reviewers. Here is what we found:

Major Themes

Books provide the bridge from theory to applications. Specifically, this means from translational and technological to clinical, from academic to industry, and from research to application.

Interdisciplinary is the new norm. Researchers identified less with a single subject area – e.g.,. chemistry, materials science, medicine etc., and tended to focus more on problems such as sustainability, artificial intelligence, or biomedicine that cut across several disciplines. This means that the range of sources a researcher uses is much wider, requiring them to dip into several different disciplines adjacent to their own core area of expertise.

There has been a move from ‘descriptive’ to ‘prescriptive’ content. The need for researchers to demonstrate real-life applications for their research when applying for grant funding has led them to seek out more applications-focused book content, rather than simply theoretical content outlining the scientific fundamentals.

Visual elements have primacy over text content. In the time-poor environment researchers inhabit, digesting information quickly is key. Several researchers mentioned video abstracts, for example, as a helpful way of quickly grasping new methods or concepts, alongside more traditional media such as tables and figures.

Trust and reputation is key. Time poverty and pressure were identified as major challenges. Many researchers spoke of increasing teaching and admin loads, and about the necessity to spend large amounts of time on grant applications, leaving much less time for research. It is therefore important that readers can quickly establish the utility of a piece of content. The reputation of the author(s), their institution(s), and the publisher for quality content are all key when a researcher is selecting quickly from a range of options on a given topic. For reference (book) content in particular, the role of references as a reading list of ‘go-to’ papers for a given topic was consistently mentioned.

How Are Researchers Using Books? Emerging Trends

Given the interdisciplinary nature of research and researchers, it was difficult to pick out distinct trends between subject areas. However, a few patterns emerged:

- Researchers across disciplines are looking for directly comparable perspectives on a given topic by a range of international research groups and find edited books to be a good way of streamlining this content in one source.

- Sustainability is a key influencer across disciplines, which is driving innovation. Scientists in all fields are looking to solve practical challenges in sustainable and ethical ways. Several researchers we spoke to were looking to make a transformative impact by applying non-traditional domain advances to their chosen field.

- In medicine, the ever-evolving nature of medical challenges (including the current COVID-19 crisis!) has led to a great emphasis on personalized treatment options as researchers seek new techniques to fight obscure and challenging diseases.

These broader trends are summarized well by Edmund Dickinson, Senior Research Scientists in Electrochemistry at the National Physical Laboratory in the UK, who commented in this interview:

The book is still prized by many researchers in science and technology as a distilled and carefully edited statement in a field. Researchers are required to become increasingly agile in terms of their ability to interpret their research in a multidisciplinary manner and may frequently have to familiarise themselves with fields of science that are distinct from their existing training. Especially in consideration of the glut of publication available in the science and technology journal literature – often of non-uniform quality – both edited chapters and monographs have an important role for familiarisation with new fields. Writing a book or book chapter may also permit a valuable pause for reflection.

What Does It All Mean? STM Books for the 2020s

As both publishers and researchers, we live in a constantly changing world. Everyone who reads this blog will be aware of the dramatic impact that digitization has had on the publishing industry in the past 25 years. As the way researchers interact with our content changes, we need to make sure our content evolves to meet their needs. Here are my conclusions on what publishers’ top three priorities need to be if books are to remain a critical part of the STM researcher infrastructure:

- Discipline boundaries no longer apply. We need to understand that our audience is now universally interdisciplinary, seeking to solve problems that cut across subject boundaries. Moreover, researchers are looking to gain quick access to, and fluency in ‘new-to-them’ subject areas and/or emerging interdisciplinary topics such as nanotechnology. It is no longer good enough to just ‘sell the chemistry collection to the chemists’. We need to make it easy for a researcher to get what they want in a flexible way that allows them to easily access a range of sources across disciplines.

- Discoverability: We need to help readers to not just find content, but also draw out the information they need from that content quickly and easily. Online content aggregators are enabling researchers to access book and journal content in the same place – they might not even know whether the original source was a journal or a book. We need to meet our readers where they are, optimizing our content in order to make it as easy as possible for them to find and use. We should be thinking about not just metadata, but also visual and even audio features, appreciating that our audience includes people with different language backgrounds, different accessibility needs and also, now, machines.

- Inclusion: One trend I have consistently noted in my time working in academic publishing is that the typical profile of authors submitting proposals to me has barely changed. It’s still very male, still mostly mid-late career academics, still mostly from Europe, North America, or Asia rather than South America or Africa. Why is this? Diversity and inclusion both within the publishing industry and within our author community is a complex problem, frequently discussed on these pages, and I will not try to solve it here. However, if we want our book content to be relevant to readers in all corners of the world, then we, as an industry, need to do a better job of embracing contributions from more diverse backgrounds, identifying those groups who are under-represented, and actively including and encouraging them to participate. The only way to ensure that we can successfully help our diverse audience of readers solve their daily challenges through high-quality reference is by actively encouraging younger authors and editors from all corners of the world and ensuring that women and men have the same opportunities.

Discussion

18 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Books for the 2020s: The Role of Book Content in the STM Researcher Ecosystem"

Thanks very much Simon, a clear manifesto for STM books! I would add that the value of book collections is often underestimated if well collated – a source for reliable reference with breadth and depth in a field (if done correctly!) Consistently high editorial and production standards – particularly for images – are I think more important for books than for journal articles, not least because it matches the reader expectation of curated and managed (and selected) content.

Thanks for this analysis. I think you missed one important trend that is particularly important in STM books, applicable only for ebooks of course, but not only reference works and textbooks. That is the need to keep updating monograph content, to keep creating new editions every couple of years. As a librarian who purchases lots of ebooks across the disciplines, and spends a lot of time analyzing the data about them, I can say with confidence that STM books produce updated editions at a pace that far exceeds anything I see in the humanities and even social sciences. And again, I’m not talking about course textbooks or reference works, but the large swath of books in the Monographs category in your graphic. Relatedly, we are also starting to see, mostly with reference works already but I am sure is coming with other e-monographs, the beginnings of seeing individual chapters being updated in different cycles from the book as a whole. This came up in recent discussion in the Project COUNTER TAG cmte, as we struggled to deal with the issue of one chapter of a book having a different “year of publication” from another chapter of the same book. This is going to inevitably lead to a significant expansion of the idea of “subscribing” to a book (paying for it again and again annually) so the user/library automatically gets all those chapter updates, as compared with making a “one time purchase” of the book. We already do this with reference works, but it’s clearly coming for other STM monographs too. This is going to create a lot of discomfort among librarians who partition their collections budgets into “books” vs “subscriptions”.

Super interesting comment, and thank you for taking the time to make this so articulately. I definitely agree with you that, not only will chapter-based publishing become more of a ‘thing’ in the future (as you describe), but, from a reader point of view, I think that the difference will be more about the type of content – ‘research’ vs ‘reference’, as opposed to the physical medium, since everything will be online, and (hopefully) equally discoverable. It will be interesting to see how new editions shake out – a constant cycle of updating at a chapter level sounds good in theory, but whether it’s desirable in practice for an author, publisher, buyer or, indeed, reader, is still up for debate, in my view.

All very interesting. It seems to me that books are now becoming the foundation of databases, I think this is happening because no one is buying books. So why is that? It is not only because they are very expensive to produce and therefor very expensive to buy but because as mentioned above they have to be up-dated at a rapid pace. In short, they are dated when published. Why is authorship within the stated observation? The primary reason is they count for little when it comes to tenure and grants. Thus, there is no incentive for an active scientist to pen a book.

Interesting comment. Hope it’s OK if I respectfully disagree with you. Reference books are about established science, and therefore should not need to be updated all the time. My experience is that this is the majority of books are not updated very frequently, and for those that are, the lifespan is more like 5-7 years between editions, in which time the field can reasonably be said to have moved on. So I’m not convinced they are ‘dated’ upon publication, as the purpose of an STM book is not to publish the latest research, but, rather, to give readers a good grounding that allows them to then explore further reading.

In terms of the ‘why write’ question, I think it’s only fair to point out that book content is cited on databases like Scopus and the Web of Science, just for the purposes of balance. In terms of the broader question, ‘time’ and ‘funding’ were identified by those we interviewed as two of the major challenges. Many therefore choose to share the workload by putting together an edited book for this reason. There are other reasons for wanting to put together the book than grant applications. I would say is that the place reference occupies in the research ecosystem is different to that inhabit by research. It doesn’t make it not valuable, though.

I think there is a wide range of cases, as some “reference works” may be stable for longer periods of time than others. I don’t think that clinicians in medicine want to wait years for updates in diagnostic guidelines, for example, whereas a reference of standard tables and calculations may not need to be updated.

I think in his hierarchy, those may be monographs, not reference works, despite librarians’ choosing to put them in their “reference collections”. But that inevitably leads to a circulation definition – a reference work (compared to other monographs) is by definition something that never becomes “wrong” (or not within 5-7 years at least according to his comment above). So if you need it updated faster, by (his) definition it’s not a “reference” book. Always interesting to get knocked out my default thinking and realize that what I as a librarian consider a “reference” book may not be at all what scientists and “their” publishers consider as such.

The necessity to provide interim updates to existing reference works with long print cycles is more urgent in the STM field than in humanities, perhaps. For example, if a key reference work has a 5-year print production cycle, there may be a need to issue at minimum annual updates to keep readers engaged with the publication and to continue to consider it relevant to current research. Some publishers are looking at quarterly online updates of important parts of their books even if the book in its entirety is not updated simultaneously.

Is there a push to completely rethink the nature of how information is shared and communicated and move to a more audiovisual based or blended learning for content? In STM is there a push to create online reference and learning environments that seamlessly blend simulations, video, dataset visualisation and manipulation with text? The original reason for the great value of books where the easy way to share, store, preserve and transport condensed information. Today this can easily be done for other formats than text. Narrative text, while still very valuable, should not stand alone. When doing user research with high school students they first look at any audiovisual content (clicking on any image in anticipation it may be a video) or look for easy digestable data in tables. They use CTRL+F to quickly find relevant information for their assignment, while reading the full narrative only as the last resort if needed for the assignments. Like with online learning there is rich opportunity to redesign the notion of how learning and information is shared in a digital format (ie. not copy past analog formats). As the article mention users like audiovisual content, but why not go well beyond video abstracts and experiment with new blended solutions?

Thanks for this. As a liaison librarian, I am sometimes a bit frustrated by the insistence of profs that students need to cite only or primarily journal articles in their papers. If you’re a first-year student in a Bio course on the science of food, and you are writing about how tofu is made (actual example), you will not find this info in an article. I would love to see more instructors structure their assignments with this pyramid in mind. Make the students cite a book or reference work in their background section, then expand upon their topic by choosing some more granular aspects and finding articles.

Heather – YES! Same here. I have frequently “negotiated” with faculty to allow students to cite references other than journal articles. Several times, on various campuses I have demonstrated, using critical thinking skills, to science and engineering faculty that we should be aiming for students (primarily undergrads) to cite “authoritative” sources be they in encyclopedias, handbooks, books AND journal articles and depending on the subject they can be more than 5 years old (e.g. an article about a species older than 5 years is really ok). For a current class, finding properties and uses of a chemical compound can be easily accomplished with several well established encyclopedias in chemical engineering and supplemented with articles.

On a more general note, finally an article that answers the question when one is attacked by non-STEM colleagues who say authoritatively “Well you don’t need much in book funds, since your people rely ENTIRELY on journal articles.”Gasp – where did you hear that?? Happened in the last economic crisis of 2009, and I am getting ready for it again! I try to express, less eloquently than this article does, some of these ideas covered here. Sometimes, when irritated, I respond with well I guess Elsevier, John Wiley and Springer etc. are crazy then publishing all these books in engineering. Silly them! (full disclaimer: I have a co-authored book published by Elsevier).

I do the usage analysis at my institution for circulation trends on print books as well as usage of ebooks, by LC class. Consistently year after year, in both formats and excluding print reserves (I have no way to exclude e-reserves use), two STEM fields keep coming up far on top in the use stats, veterinary (we have a vet college) and nursing, with biology and English usually neck and neck at a distant third. So much for the humanities being the big users of books. And the vet and nursing programs are both capped in enrollment.

On the other hand, I am often frustrated by humanities faculty teaching those intro freshman comp classes insisting students use “at least 3 books published within the last 10 years” when they’re also approving topics (eg ones that have only surfaced in the world in the last 2 years) that there is really no chance we are going to find books on, only articles. I waste a lot of time trying to help those students figure out how to find a tangent/pre-cursor to their topic that we can find in books that they can weave into their papers just to satisfy that requirement. Not teaching good scholarship there. Such restrictions in both directions do not serve in the information literacy needs of the students.

Taking books from a slightly different aspect, I’m surprised how many researchers tell me they mark up print copies, but still have difficulty marking up eBooks (even pdf) outside of the Kindle.

I think there’s an untapped market there.

As a librarian, I shudder every time I hear of a survey of user preferences for print vs e books in which the primary argument from the pro-print users seems to be their desire to mark up the books! To a librarian’s ears, that’s exactly a reason NOT to give them any more print books. And to those who think, “oh, they wouldn’t write in a library copy, they just mean their own”, I beg to differ. We get books back all the time with all kinds of highlighting and scribbles in them. Because we don’t have time to inspect every outgoing book, we can’t hold any one particular patron accountable (literally, fines) because they can always claim those marks were already there when they got the book and we can’t disprove that. But it is happening all the time. To those who really love to hold a print book, maybe add this to the “this is why we can’t have nice things” list.

This is why scholars buy print books themselves. Library digital copies are used for search and skimming, an individual’s print copy is used for engaged reading. Most academic books are purchased by individuals, not libraries.

I can’t help but chip in here: I’m an ex-scientist and digital publishing professional turned Humanities student. While on lockdown our university has added extra e-books to help with access. I frequently print out chapters for easier reading, annotating and so I can have several chapters open at once on my desk: e-books just aren’t as handy.

(Btw secondhand online bookstores have also become a lifeline, because a lot of fantastic humanities books aren’t available online.)

Interesting insights from the research, particularly around the discipline boundaries, not least because these boundaries are a major part of academic identity, and publisher identity too.

On books, I think STM reference content will need to evolve into decision tools, running across those disciplines. That seems to me a huge challenge for the way academic publisher processes are set up.