Every day, choices are made, and positions advocated, about the best organizational forms for providing the various services needed for the academic enterprise. This is an important, and underexamined, issue for academia. As well-resourced as some universities are, they are not infinite in size, and, as a result, they have to prioritize their investments. When purchasing or developing scholarly communications services, library systems, and research workflow tools, individual universities seek cross-institutional scale — that is, if multiple institutions require the same tools, there are efficiencies in having one tool made for all these institutions. Scale can be achieved in a variety of ways, including open source software, institutional partnerships, consortia, and outsourcing to third-party organizations, both not-for-profit (NFP) and commercial in structure.

The two of us have been debating for some time which services should be controlled directly by the academy and which services are best provided by third-party vendors, many of which operate as for-profit enterprises. Roger has written extensively about this, for example this article and this article, arguing that many academic institutions and their collaborative vehicles have not developed the strategic or governance posture necessary to offer a realistic alternative to commercial enterprises. Joe has analyzed some of the reasons that the academy has outsourced scholarly publishing in particular, largely (but not entirely) to commercial firms. These conversations take place against a backdrop in which some believe that the academy should “should step up to invest in home-grown research infrastructures and cross-institution consortia”, while others, of a free market persuasion, believe that commercial enterprise solves virtually all problems. Not surprisingly, we fall somewhere between the two ends of the continuum — and toggle from left to right and back again depending on circumstances. While we don’t have a prescription for determining which service should fall into what bucket, we have been developing a list of questions to help make these judgments.

To Outsource or Not to Outsource

If a need for scale is a reason to look outside an institution, it follows that activities that don’t or can’t or shouldn’t scale should be kept in house. This may sound like a backwards way of stating the principle, but in fact universities exist in part to do non-scalable, mission-based work. For example, there would be little sense for a university to come up with a rival to Google Docs or Microsoft Word, scalable applications of the first order that have a purpose well beyond the academic context. And many institutions have outsourced support functions, such as grounds maintenance, food services, and custodial work, to a variety of third parties. At the same time, although some smaller institutions have experimented with sharing academic courses and programs, it would make no sense for a university to outsource a core academic function such as its history department to a third party — it either has a history department or it does not.

To our eyes, the more interesting examples are those that fall in the broad middle zone, neither self-evidently requiring outsourcing nor so core to the academic mission that they must be held in-house. For example, what about an innovative form of word processing software that is designed for writing interactive fiction? It might be difficult to see why or how an outside organization would choose to create such a tool. In practice, such a project could be developed initially in a digital humanities department, for use by that department and a small number of practitioners in the field, perhaps with grant funding. In many cases, perhaps most, that will be enough: the tool will be used for several years and then, as the grant funding expires and a small set of existing users moves on, it will no longer be supported. But what about the rarer but vital cases where such a tool not only fulfills its grant-funded mandate but proves to have broader value? In this case, the demands for improvements, the need to scale system capacity, and various essential maintenance tasks will cause it quickly to outgrow its initial home. Should the tool’s code be released as open source, enabling others to build upon and maintain it? Should a new NFP organization be created for such a purpose? Should an existing NFP be assigned responsibility for it? Or should it be sold to a profit-seeking corporation? We can point to examples of leaders making each of these choices.

Organizational Categories

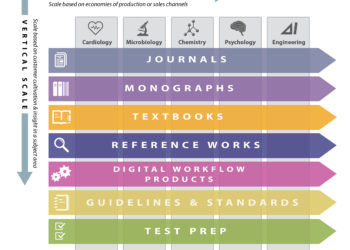

When an activity outgrows a given institutional context or clearly benefits from a cross-institutional scale, it can, broadly speaking, fall into one of three categories:

- The first of these is the consortium. While some readers will immediately think of the library consortium, here we broaden that definition to include a variety of membership organizations in which organizations, not individuals, are the members, and they work together through the consortium to provide a scalable service for the overall benefit of the community. Major examples in this category include the Big 10 Academic Alliance, HathiTrust, Crossref, LongLeaf, OCLC, ORCID, and the Center for Research Libraries. Some university systems’ central offices, such as those of SUNY or University of California, can be seen to fall into this category as well. These consortia are characterized by an ultimately collaborative governance model. Some are discussion groups or buying clubs with relatively little organizational heft, while others have developed substantial capacity and services. While some of the most recently formed have adopted novel governance models fit to purpose, others are in various forms of governance crisis, including those traditionally governed organizations that have become product organizations desperately in search of greater agility (a topic Roger has written about elsewhere).

- A second category is the scholarly society, a NFP typically organized on a disciplinary or other field-specific basis. At the Scholarly Kitchen, we encounter these for their extensive publishing work, but they also run conferences, provide education, organize the job market in their fields, write standards, and provide a variety of additional services. Major learned societies include IEEE, the American Society of Hematology, Massachusetts Medical Society / New England Journal of Medicine, and hundreds more. These NFP service providers are operated as businesses, but they are mission-based; their ultimate overlords are not shareholders but individual members, who themselves are typically academics.

- Finally, we get to the third category, the commercial for-profit providers of services. This group is as well-known as it is vilified — often unjustly, in our view, as they provide services at a scale and economy that would otherwise be difficult to obtain. Such companies include EBSCO, Elsevier, Mary Ann Liebert, Clarivate, ProQuest, SAGE, ResearchGate, and countless others. Some of the largest commercial organizations in the sector are publicly owned (and indeed you may own a portion through your retirement accounts), but also common is private ownership, through families, private equity, or venture capital.

There are several other categories as well. For example, there are NFPs that are organized not as membership organizations but rather with self-perpetuating boards of trustees. And, there is the much-heralded prospect of open source software, which some argue can be managed independent of any focused organizational home, although we often see the involvement of a NFP such as Lyrasis or Coko (or a for-profit such as EBSCO). Another obvious category could be university presses, but since these are organized as components of individual universities they are an example of in-sourcing rather than cross-institutional scale. For discussion purposes in this piece, however, we believe that these three models — consortium, society, and commercial — offer enough breadth to examine the varieties of outsourcing. Each has its virtues and limitations.

Tradeoffs

Let’s look at the distinction between an NFP service provider (in either of the two categories discussed above) and a commercial provider. Both operate as businesses: the former seeks to generate a surplus, or at least to break even, the latter seeks a profit. The former takes its surplus and reinvests it into other mission-based activities (e.g., subsidies for society members for conference attendance) without those surpluses being taxed; the latter invests some of its profits into new programs and expansion, paying taxes on the rest and remitting the remainder as dividends to shareholders.

Why wouldn’t the academy prefer the NFP to the commercial firm, since the NFP, like a university, is mission-based? In fact, many members of the academic community do indeed express a preference for NFP vendors for just this reason. There is often a strong desire to build organizations that align on a values basis with the academic sector. Still, the success of commercial firms in so many areas (in publishing, the biggest examples, of course, are Elsevier, Springer Nature, Wiley, and Taylor & Francis) is clear evidence that for-profit firms have something to offer.

Ultimately, an NFP and a for-profit firm have certain commonalities. At the most basic level, both have to operate in the marketplace, creating products and seeking customers, and trying to align their cost structure such that it is less than revenue.

Having to operate in the marketplace provides certain advantages to the for-profit firm. For one (and this is a very big one), the for-profit firm has much greater access to capital. Note that three of the four large publishers mentioned above are publicly traded, a capital structure that is simply unavailable to NFPs. Another factor is likely to be governance, as for-profits have governing boards whose aim is to further the success of the business, whereas in the NFP area, the board will necessarily have multiple, often competing, priorities. In the NFP sector we also have the sad spectacle of governing boards who simply look at certain business lines – for example, publishing –a s a source to fund other activities, resulting in insufficient investment in operations and new initiatives. Today these NFPs are the competitors of for-profit firms; tomorrow they will be their lunch.

Where the societies typically perform well against for-profit entities is when a membership can be mobilized to support services. Typically, this is accomplished by taking a vertical slice of the market — an organization that only provides services for radiologists or orthopaedic surgeons or literary scholars, for example. Such organizations are likely to have a broad range of activities (publishing, continuing education, conferences, job placement) all focused on a single domain. In other words, the focus on membership is a critical success factor, a focus that at least partly offsets the market-based advantages of the for-profit firm. The importance for societies of a community is not only in a shared mission but also that a community can serve as a bulwark against market inroads by a for-profit rival.

The consortial strategy presents a different set of tradeoffs. For example, both commercial publishers and society publishers (which are not-for-profit) operate in the marketplace and are subject to the market’s impersonal nature, but consortial arrangements are mostly set up to operate outside the marketplace. The good news here is that consortia can thus develop services that may be unlikely to turn a profit, and perhaps even generate a loss. For example, they are particularly good at operating as standards bodies, which cut across multiple organizations (and for which commercial firms participate cautiously, out of fear of being accused of anti-trust violations). Or, to take another example, they are good at helping a group of institutions to achieve digital scale when control of the platform is a higher priority than strategic or technical agility. On the other hand, the absence of market competition can lead to undisciplined behaviors; some consortia have held on to services for which there is only the smallest demand. In other cases, the financial success of a consortium has counterintuitively allowed its focus to drift beyond the core interests of its members. Our view is that consortia that build community-wide resources have a special role in the overall scholarly communications ecosystem, but they are likely to trip up in providing services in direct competition with commercial organizations. For example, it is difficult to imagine a commercial venture providing HathiTrust’s Emergency Temporary Access Service, but it is unlikely we will see an academic consortium easily supplant Springer Nature or the American Chemical Society.

While we do not always agree, even between the two of us, on exactly where the balance should be struck, there are certain areas of substantial uncertainty that we both acknowledge. As software becomes an increasingly important element of instruction and research, for example, the question about how best to develop and sustain first-class software offerings — to support online learning, the research enterprise, library management, and so forth — illuminates the tensions plainly. Because the opportunities presented by cross-institutional (and indeed sector-wide) scale are so great, and because of the risk of a winner-take-all market structure is very real, some observers have sought open source or consortial solutions. But because the need for capital investment and agility to create and sustain software enterprises is also so great in a market ecosystem, commercial enterprises also have a meaningful advantage over many other organizational models. Whatever our individual preferences might be, this tension has been one of the most important dynamics in a number of adjacent sectors over the past decade and stands to remain central for the foreseeable future.

Summary Characteristics

To summarize some of the key differences between these three different types of organizations, we propose this table of some key characteristics of consortia, societies, and commercial enterprises and where they converge with or differ from one another.

| Consortium | Society | Commercial | |

| Mission | Serve the needs of the members, often with a clearly specified area of focus | Serve the needs of the members, often by generating a surplus on some activities that cross-subsidize others | Serve the interests of owners, depending on corporate form emphasizing something between short-term results and long-term value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance | Governed by organizational members such as libraries, presses, or universities | Governed by individual members, such as academics or other professionals | Governed directly by owners or, at a certain scale, by a board purported to represent them |

| Strategy and Focus | When elections to governance roles are relatively open rather than tightly controlled, board members do not always represent the interests of the members. Moreover, strategy can change fairly quickly and the sustained focus necessary to execute on strategy may therefore be absent | A professional society may find tension between the business and member sides of the organization, with each side clamoring for greater attention and funding | Trategy is adjusted subject to competitive dynamics (or ownership changes), but otherwise commercial enterprises can sustain as much focus as management determines necessary |

| Nature of scale | The largest and most financially successful consortia typically require governance models that are more removed from the practices and needs of individual members | Most societies require greater scale than they possess for publishing platform or publishing services, which in many cases are obtained by partnering with or outsourcing to other (mostly commercial) publishers | Several rounds of acquisitions have created most major commercial players, in both the primary publishing and adjacent platform sectors (though some, like ResearchGate, are products of organic growth) |

| Access to capital | Rarely possessed of extensive working capital; capital infusions can be sourced from members (rarely) or foundation grants | Professional societies can access debt markets and also receive tax-deductible grants and donations, but they are denied access to public equity markets | When their businesses are competitive, they have reasonably assured access to capital through equity and/or debt markets |

| Social policy (e.g., privacy) | Often attempt to speak for the benefit of society as a whole (the public good) | May attempt to speak for the benefit of society as a whole, but perspective may be skewed in favor of members’ interests | Compliance with applicable law is the heart of a for-profit’s social policy, but it may champion certain issues of interest to its customer base |

| Ability to thrive in a competitive environment | Consortia can be very effective in representing the needs of their members on exclusive matters, such as collaboration, policy, or acquisitions. Because of the nature of their governance models and limited access to capital, they are rarely agile enough to prosper when there are competitive alternatives | A well-governed professional society can be a formidable competitor (e.g., ACS, IEEE).This requires an awareness on the board level of the need to invest in its commercial operations. The area where competition is very difficult is the ability to operate at the largest scale because of lack of access to capital markets | While commercial firms can have management shortcomings, even the most entrenched incumbents can innovate when faced with marketplace competition |

We could easily add to this list — a bullet point for talent management springs to mind, where for-profit entities can outshine their competitors to the extent they are willing to pay for talent and results. Oh, and did we mention governance? We would be happier, though, for this list to be augmented and refined collaboratively. We hope to identify some good ideas in the comments to this post. Fire away!

Discussion

14 Thoughts on "Good vs. Evil? Finding the Right Mix of For-Profit and Not-for-Profit Services"

The tendency of some members of the academy (as well as some professional societies) to prefer not-for-profit vendors or partners in some circumstances but not in others remains a source of bewilderment. I have been in rooms where academic board members are adamant about partnering with a not-for-profit publisher or using a not-for-profit software vendor for publishing. But yet I doubt that same faculty member would insist on using a not-for-profit software vendor for, say, the university’s accounting systems. Or would insist that the new wing of the library is built by a not-for-profit construction firm or that the grounds are maintained by a not-for-profit landscaping company. Should the new CT scanner for the medical center come from a not-for-profit engineering firm? Should the professional society’s annual meeting be supported by a not-for-profit trade show vendor? Certain aspects of scholarly communication appear to occupy a different sphere than the rest of the academic enterprise, perhaps because they are more visible than other matters to researchers and also closer to mind. As you note, it is not obvious that not-for-profits have an edge in commercial activities such as publishing (and related software). Associations and universities might be more clear about the reasons for preferring not-for-profits over for-profits in certain circumstances — and why those circumstances are exceptional.

One reason why you’d want to go with a not-for-profit or community-owned supplier over a commercial one is lock-in, and the pain involved in switching platforms. If you have a choice of an open standard versus a proprietary one, then the open standard keeps your future options open and can save a lot of heartbreak later on. You need to get the functionality that you’re seeking, but if you can do that through an organization that returns your investments to the community and that doesn’t lock you in, then I would think that it’s a no-brainer in situations where possible.

Not-for-profits are perfectly capable of creating lock-in. You need look no further than one mentioned in this piece – the American Chemical Society – as an example. Spectacularly successful at doing so.

Understood, there’s nothing magical about not-for-profit status that makes you a good guy or makes you play fairly. Kent wrote a nice piece about this in 2017:

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2017/08/08/false-equivalency-are-non-profits-inherently-superior-to-for-profits/

That said, at least in my experience, the not-for-profit status reduces fear of your vendor being sold to a competitor, and in general, organizations that are governed by the community can’t really offer the same lock-ins because they’re not run by a single entity (and perhaps I should be speaking of these types of organizations as a subset of the NFP realm, rather than generalizing). But with that, as the post above points out, come some negatives (such as reduced capital, etc.).

Also curious to see where you feel ACS is serving in a vendor:client relationship and imposing technological lock-ins on customers due to proprietary formats.

Lock-in can matter with regard to software and services, but the devil is very much in the details. One can structure a “take-it-with-you” license in some cases with commercial software. With open source, you may be able to take it with you but then you have to service it (and may not have the resources or expertise to do it or there may be other non-open dependencies and licenses). I agree completely that these are important considerations but these carefully balanced tradeoffs are not the decisions I was referring to. I was talking about preferences, often made at the board (or editorial board) level based on cultural factors and not on technical considerations.

As to whether an organization returns investments to the community, that is also a matter of nuance. One could argue, if one were of a mind to stir the pot, that a large UK-based university press returns money to its parent institution, which is nice if you happen to work or study there. Whereas a large publicly traded publisher returns money to all of its shareholders, which include a broad array of university endowments as well as the pension funds of faculty and staff.

Fair points all, but I was thinking more of community-owned organizations like Dryad or ORCID providing services (e.g., ROR versus Ringgold) rather than not-for-profit publishers. In each case, there are balances and questions to be asked — a blanket “we only deal with not-for-profits” policy is unlikely to be realistic or even possible. But I think it’s perfectly reasonable, all other things being equal, to have a preference toward non-profits (and personally, I’d rather the money I have to spend go to paying for scholarship and research, even if at a single institution, than into the bank accounts of Wall Street).

Another thought here is that many service providers are being bought up by the larger commercial publishers, which means that hiring them on is putting money in the pocket of one of your direct competitors. A not-for-profit is less likely to be sold to your competitor, so that may be a determining factor as well.

This provides an excellent answer to the question “What form of governance and organization works best in a market economy?”, and the answer is (big surprise) the for-profit firm. If the question were framed differently, the answer would certainly be different. For example, if we asked “What form of governance and organization works best to produce public goods?”, then I suspect that the ways of measuring success, and the actors being considered, would be quite different. I see two actors missing from your analysis that would need to be included if you re-framed the question around public goods rather than efficiency, scale, and access to capital. They are the commons and the government. There are a growing number of examples of commons-based approaches to producing public goods that are worth exploring and learning from. And while people love to mock the Post Office and the Department of Motor Vehicles as models of why the government should be as small as possible, there are many good examples of how the government can play a key role in the creation of what are usually considered to be commercial goods and services. If you read the history of technology innovation in the US, you’ll learn that once upon a time most of the innovations that companies like Google and Apple are based on arose from basic research that the government either funded or ran out of their own R&D operations. The broader point I would make is that in this seemingly inescapable neoliberal moment where the state is defunding public education and privatizing everything it possibly can, it is no surprise that efforts to create public goods are cash-strapped. If we think about scholarship as a public good, and ask how the significant amount of capital that we as a sector currently invest in this enterprise might be organized to support these public goods, we would likely arrive at answers that look quite different than our current arrangements. I would welcome more analysis of alternatives to market-based approaches to creating public goods, as well as further discussion on whether or not scholarship is a product to be sold or a public good that requires a different framework and funding model.

Well, clearly you did not read the post. That is exactly what the post says: different questions have different answers–though we managed to make this point without invoking the (shudder) bogeyman of neoliberalism.

Joe, I actually read it not once but twice, but who’s counting? :> While your analysis is well-informed and nuanced, it assumes that all of this takes place within a market framework. (That is, as you know, one of the basic definitions of neoliberalism.) My comment was meant to suggest that if you frame scholarship as a public good rather than as a commodity to be bought and sold, then notions of funding, organization, and governance are quite different. For example, you can tell the story of the university press losing support from universities because they are not breaking even as a chapter in the long story of the shift of the university to the logic of the marketplace.

Mike, Thanks for weighing in on this. In this case, though, we are focused less on the creation of public goods than perhaps we once would have been — after all, as many have argued, funding model of higher education in the US and elsewhere has shifted over the past several decades towards being much more of a private good. Thus yesterday’s piece is a “world as it is” rather than a “world as we wish it might be” analysis of how higher education institutions can produce services together that they cannot or had best not produce alone. We included several entities that are directly government funded — for example OhioLINK and SUNY — in the examples we offered. We also referred to several open source software models, which I think many would consider to be “commons” approaches. If you would like to draft a piece on other alternative models for supporting the kinds of infrastructure and services we covered in this piece, though, I would be thrilled to help get it published in the Kitchen!

This post is a great contribution to the debate about optimal types of organisational delivery mechanisms and what role commerce has in the academy.

I’m holding myself back from weighing in on the (pernicious but false) presumption of “NFP = good but commercial = evil” that infests this sort of discussion. But I will raise two points that don’t seem to have been sufficiently explored.

One is Risk:

If a commercial enterprise spends time and money on developing a new product or service, and it turns out to be a failure, it is (broadly speaking) the shareholders / investors who suffer the loss from this failure. Whereas when projects run by government-funded, NFP or similar organisations fail, the cost of that loss falls on the commons, not the capitalists. I feel that people do not consider the cost of risk enough in these discussions.

The other is Tax:

Many not-for-profits are strongly revenue-generating and have significant surpluses that are not taxed and are not returned to risk-taking investors, both of which seem to me to be economically desirable (at reasonable rates). What happens is that these organisations hoard their surpluses, or have them confiscated by parent institutions (as in the society or university press examples) or squander them on vanity projects. All of these negative behaviours can be facilitated by the poor governance that is quite prevalent in such organisations.

Finally, there was a workshop at the Researcher to Reader Conference in February which also explored ‘commerce in the academy’, although it repurposed itself more into a discussion about optimal roles for the stakeholders across the landscape, choosing to ignore the ‘Twittersphere’ issues of ‘profit’ and ‘resentment’. A glimpse into the workshop can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YMltkkTivvU&t=19m1s

[Disclosure: I manage the R2R Conference – it is currently very much ‘non-profit’, but that was not really my intention!]

Thanks Mark – I agree that risk and tax are two areas that could productively be added to the table. I’ll try to check out the workshop video as well.

Mark, thanks for posting this video link – very interesting – but especially because the next part of the video was a report out on the funder transparency Plan S framework that I had been wishing to hear about. Nice coincidence!