In Chris Miller’s superb Chip War, there is an intriguing anecdote about the young, talented Morris Chang. Chang enrolled at Harvard to study Shakespeare, but during his freshman year, he began to have doubts about his job prospects. So in his sophomore year he transferred to MIT, where he majored in engineering. After MIT he went on to earn a PhD in physics from Stanford, giving him the trifecta of academic credentials. After many years at Texas Instruments, he founded TSMC, the semiconductor manufacturing company that lies at the heart of Xi Jinping’s craving to “reunite” Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China.

One wonders what would have happened had Chang stayed with Shakespeare instead of creating one of the ten most valuable companies in the world. Would he have transformed Shakespeare studies and, by extension, the humanities in general? Or would we now be listening to our instructors while inditing notes, as the Romans did, on a wax tablet?

The Chang anecdote comes to mind as I have been pondering a recent essay in The New Yorker, “The End of the English Major” by Nathan Heller. Because this is The New Yorker, we must be alert to the irony in the title, the mock melodrama intended to tweak the many English majors among its readership. Heller’s argument is based on the startling fact that the enrollment of English majors, and in the humanities more broadly, has dropped precipitously, with some institutions reporting declines of as much as 40%. Language departments are being consolidated and new staff positions are hard to find. One can imagine competing choruses (dressed in togas, reciting in precise meter): That is absolutely terrible!, or It’s about time! Unsaid is the possibility that with the decline of the English major, The New Yorker will gradually disappear as well. The English major is not simply an entry in the registrar’s log but a central component of an ecosystem that includes writers, readers, playhouses, the genre of costume drama, and many text-based publications, from The Atlantic to the staff of The Chronicle of Higher Education, and reaches into the intimate education of the people behind The New York Times, NPR, and PBS. Banish the plump English major and banish all the world! (Yes, that is a paraphrase of Shakespeare.)

Heller has interviewed a number of people, principally from Harvard and ASU, presumably representing two poles of higher education in the U.S., and he carefully injects a hint of The New Yorker’s trademark technodystopianism, but overall he seems to me to have captured a reasonable picture about how the humanities are being thought of on campus. What kind of job can I get if I study John Donne, James Baldwin, and Virginia Woolf? Isn’t the study of literature at bottom really a hobby? What we need are majors that produce tangible outcomes, and that means STEM, STEM, STEM! I offer these cheering thoughts to the many PhD’s in the life sciences who shuffle from one adjunct teaching position to another or are stuck as career postdocs.

The other side of this is, what happens when students don’t study literature? Who will protect us from bad spelling, dangling modifiers, or, God forbid, the use of “privilege” as a verb? One professor notes that her students seem to have trouble grasping a basic understanding of the sentences of some works and wonders if literacy itself is at risk. Her specific example is The Scarlet Letter, which I took personally, as Nathaniel Hawthorne is one of my favorite writers, especially for his short stories. But there is a place to consider whether the syntax of Hawthorne or, say, John Milton’s Paradise Lost prepares a young person for PowerPoint presentations, spreadsheets, and Zoom conferences. Even so, I wonder if we should not be picking on just English majors here. I have myself been bewildered by some writing in the social sciences, including occasional guest posts on The Scholarly Kitchen, where the level of abstraction is so great that I can’t for the life of me figure out what the hell is going on. Maybe we need to do some more thinking before we shrink humanities departments further and stuff them in a closet.

Allow me to confess that I was myself an English major and find it troubling to be regarded as a citizen of a lost civilization. Having said that, I bear no grudge against the hundreds of people with technical educations who worked for me over the years. And, as far as I know, they weren’t overly miffed when I would occasionally remark at a marketing presentation, “Wow! That was a nicely turned phrase!” I can’t say that being an English major made me more or less employable, more or less effective at my job, or a better person. There is no direct line from what one studies as an undergraduate and one’s ultimate profession. But Robert Burns said it better: “The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry.” The line is addressed to a mouse.

Into this backyard skirmish of the Culture Wars steps Ross Douthat of The New York Times to proclaim that “I’m What’s Wrong with the Humanities,” and he inadvertently makes his case. Douthat’s argument is that in a world of blog posts, newsletters, and social media, he no longer can wade through a work by the Brontes or Jane Austen. This is a head-shaker: Does he really believe that the 19th-century English novel is a metonym for literary study? It takes little imagination to see that literary study has much to tell us about new forms of media, from tweets to the Metaverse. Douthat has forgotten that in 2016 the time was out of joint (in Hamlet’s phrase) and we saw not only the election of Donald Trump but also the awarding of the Nobel Prize for literature to Bob Dylan, no Anthony Trollope wannabe he. (More incontrovertible proof that a rift opened in the universe in 2016 can be found in the fact that the Chicago Cubs won the World Series.) Perhaps the study of literature has become more loosely defined, more diverse, always evolving. Perhaps college is not about job training after all.

For the time being, however, this argument — my argument — is losing, and those of us laboring in scholarly publishing have to be prepared for this. Although I believe that things will swing back when enough chemists find themselves reporting to philosophy majors, we have to think about the ecosystem in which we work. A 40% drop in humanities majors, if it persists for even a short while, will ripple through the field: fewer graduate students, fewer professorships, and ultimately fewer publications. I am thinking particularly about the university press world, which I acknowledge is my favorite sector of all in scholarly publishing. Some years ago I worked on a project that determined that 28% of university books were in history and 16% were in literary criticism. I don’t know what the numbers are today, but even if they have declined by half, the university press world is highly dependent on those disciplines.

Predicting retrenchment in university press publishing is something of an annual affair, but right now we may be facing a significant resizing of the infrastructure of academic book publishing. And it must be said: Open access can’t help here, as the problem is not access but diminishing research, publication, and readership. I do suspect that many provosts will be thrilled to be able to rid themselves of their university presses. But if the pendulum does swing back and some knowledge of Tennyson and Elizabeth Bishop is viewed as the mark of an educated person, we may not have enough ships to carry us to Troy.

Discussion

17 Thoughts on "Fallout from the Implosion of Humanities Enrollments"

English programs are being cut because ever fewer young Americans want to pursue an English major. Some of the decline is likely due to the perceived value of a BA in English in the job market. But could another factor be at play here? Do today’s high schoolers perceive English as a difficult subject, like, say, chemistry?

My choice of chemistry is deliberate. Of the three basic sciences – Biology, Chemistry and Physics – it arguably provides the surest path to a well-paying job. Yet the numbers of chemistry majors, while not declining, are hardly rising with the STEM tide.

I suspect few students casually choose to major in chemistry. Could that now be the case for English?

Perhaps folks who would be interested in majoring in English really want to be writers and spending countless hours reading and analyzing works by others isn’t the path they want to take? These folks are likely avid readers anyway, do they need to spend hours pursuing that from an academic perspective rather than working on their craft? Sure, analysis of great literature no doubt helps you with your own, but there are more direct paths.

I can’t help but wonder to what degree the decline in English majors (and humanities majors generally) has to do with the degree to which the study of the humanities has been turned into the study of social sciences instead. Increasingly, over the past decades, it seems as if understanding literature has become conflated with understanding the history of social injustice — a very important topic, certainly, but not necessarily the one that young people who really want to study literature are hoping to undertake. If I were getting ready to start college right now and were in love with literature, I’m not sure how confident I’d be that majoring in it would be the most fulfilling way to pursue that love.

Well, Joseph, please accept this comment from a 1973 English major who is not a member of Scholarly Kitchen, but who occasionally enjoys your contributions here, whenever my email avails them. You may find the historical narrative below edifying. If not, toss it over the transom.

Having studied English and Political Science at LSU, I set out for Florida, having acquired a family-connected job insurance. I tolerated that for nine months, then gravitated toward newspaper advertising–not a bad match for and English major, n’est ce que pas?

Long story short: Years of selling for a print shop in North Carolina, which slowly morphed into a career of carpentry. (Go figure; it was in the family.) Along the way was one failed attempt to found a newpaper.

By ‘n by, after a failed attempt to break into teaching high school, my 9 courses of post-grad Education propelled into an avocation of writing novels, starting in 2007. Novels I have written: Glass half-Full, Glass Chimera, Smoke, King of Soul.

Thank God for Jeff Bezos; I was able to publish them. Random House, eat your heart out. And thank God for my wife, an ICU Nurse. And thank God for our three young’uns, who are living productive, literate lives.

Lastly, as an avid consumer of history, I have composed and published 1200 blogs re: mostly the times we live in.

Most recent contribution to our national security is my composing a third verse of our National Anthem. “Oh say can you see, in the 2021 light, what we so proudly retained, after a riotous fight. . . Oh say does that Capitol Congress remain. . .?”

Thank you for tolerating, if you have read this far, my non-membering improvisation on a theme by Joseph Esposito. Keep up the good work at Scholarly Kitchen. http://www.careyrowland.com.

Not to be snarky but to correct an inaccuracy, our National Anthem has four verses. I remember singing them all in rotation in grade school. As an aside, I couldn’t find all four verses easily with Google text search, but ChatGPT provided them quickly. I could find a Google image of the complete text, but couldn’t cut and paste it here.

Verse 1:

O say can you see, by the dawn’s early light,

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight’s last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight,

O’er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming?

And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there;

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

Verse 2:

On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep,

Where the foe’s haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o’er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning’s first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream:

‘Tis the star-spangled banner! O long may it wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Verse 3:

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle’s confusion,

A home and a country should leave us no more!

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps’ pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Verse 4:

O thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand

Between their loved home and the war’s desolation!

Blest with victory and peace, may the heav’n-rescued land

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation.

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: “In God is our trust”:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!

What the New Yorker piece failed to argue, was that students in STEM can benefit greatly when humanists are integrated into the STEM program. Imagine if your premed course included classes in ethics (taught by a philosophy professor), communication (taught by an English professor and someone from the Communications dept.), and diagnosis (taught by a historian of medicine). I suspect that the Medical Humanities, a very diverse field, may now be larger, and better funded, than the rest of the humanities combined. Personally, I’d be happier in a world in which clinicians, bankers, and technologists had some cursory experience with the humanities than in a world where the expert on Proust sat alone at the back of the bar muttering to himself over his glass of absinthe.

I’m unconvinced by the perception that certain college majors lead to better personal outcomes, whether financially, professionally or holistically. We may be able to measure the mean and median salary of working chemists whe are Americal Chemical Society members, but that data is published by ACS, a society that is dues collecting and many chemists may not be a member of, and few former chemists would be a member of. If out of 100 chemistry graduates, 30 are members of ACS, then we really have no idea of the relative merits of the degree if the data excludes the other 70. My personal feeling on the matter is that the top 25% of chemists get employment in the field and the other 75% end up doing something else as automation has revolutionized the industry. If better data is available, I’m quite curious to know.

I wonder how much of it is because of the assumption that you can study literature and history on your own time, when you have a good paying job because you got a degree in a STEM field? Our book club just finished James Joyce’s Ulysses. It took six years….(but plenty of decent wine to help struggle through it).

The other aspect that strikes me is something a university career counselor was telling local kids in the neighborhood who were thinking of applying to college: An undergraduate degree will be the last time you can pick a topic to study in depth because you want to, not because you have to.

A rather bleak assessment but with a grain of truth.

Funny thing you mentioned Ulysses. In my local Writers’ group, High Country Writers (of Boone, North Carolina) my fellow authors were critiquing a piece of writing that I had presented to them for their critique. The .doc was an experimental writing that was somewhat uncategorical. Maybe it was a poem, or maybe it was the beginning of stage play. The piece, as I composed it, included allusions to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, Edgar Allen Poe’s the Raven, but I concluded it with an obtuse protestation about the state of our nation because of the influence of one man, whom I shall not mention here.

Our discussion meandered into other topics. At one point, being the author of the critiqued piece, I lamented that I had started reading Ulysses three times, at three different seasons of my life, but I was unable to “get into it.” My writer friend, Richard, who was sitting next to me, mentioned that James Joyce, like Hemingway, Fitzgerald and several other notable authors were heavy imbibers, and that he himself was quite the appreciator of drink.

However, I do not share that dependency, although I do have a nip or two daily.

Bottom line: English majors should have a little vino from time to time so that they can enjoy their low station in the world. With that said, I will celebrate the fact that Bob Dylan proved that poets can, in truth, amount to something noteworthy in this life. Cheerio.

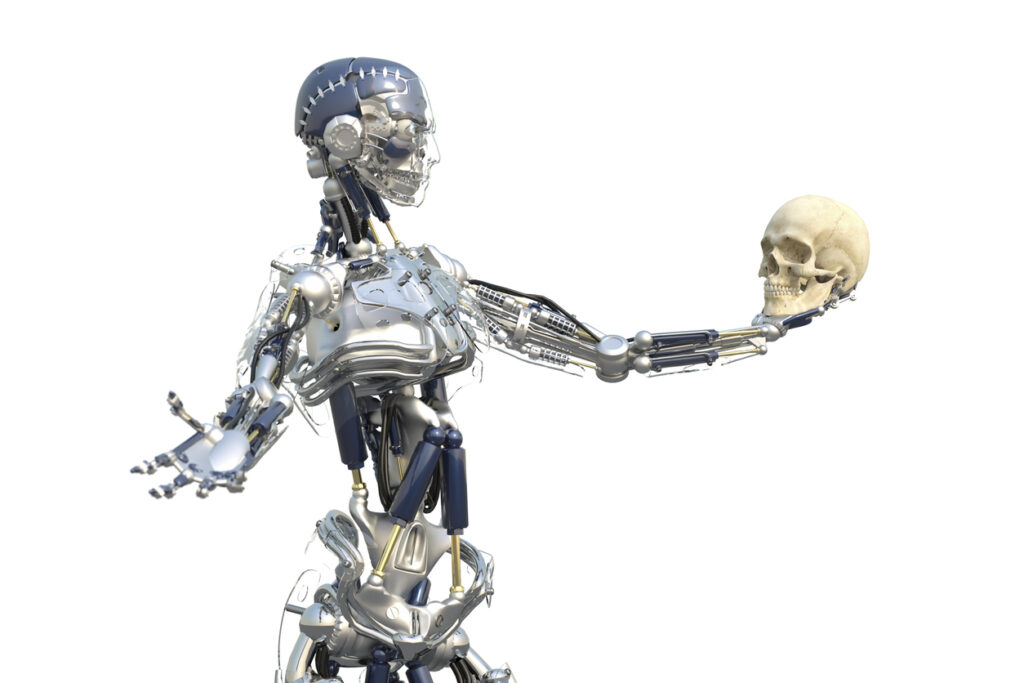

I wonder – ‘hope’ is perhaps the better word – that the explosion of AI will wake our society to the need for the humanities. With the likelihood of AI and digital technologies’ ability to, for instance, detect and anticipate disease even before an individual’s suspicions emerge could arguably create unprecedented capacity in the medical industry (yes, I am an eternal and irrational optimist). Can’t (shouldn’t?) this capacity be directed at pondering the very important question of what it means to be human? And does this question not find its best home in the humanities? Does literature then not find a new function as sage wisdom? A reminder of what it meant to be human pre-4IR and thus a guide for us to retain and build on that humanity in an irrevocably transformed world? We are entering a world where codes can now generate it’s own codes and humans should work harder and more intentionally at developing its own humanity. The challenge now is to ensure that these two processes unfold in ways that are not mutually destructive, but mutually constructive.

Your hopeful response here is quite an inspiration. Thank you for raising it! Let us get right on it!. . . the re-humanization of the Humanities.

With the advent of ChatGPT and similar AI programs, I fear for the worst when it comes to humanities education. Soon AI will customize history textbooks to suit the demands of each state’s preferred flavor of past events. Similarly, with the banning of books, fewer students will be introduced to great literature. Sadly, it will matter little in a nation with a TicTok attention span. The ability to write persuasively and articulately will not hold the same value when nearly everyone becomes accustomed to feeding prompts to their personal AI assistant who does their writing for them. He who controls the AI programs will control the minds of the masses who they feed with propaganda of their choosing – hello Siri and Alexa. The study of peer-reviewed history and deep literature will be reserved for the truly devoted. The gulf between the “poorly educated” and “academic elites” will widen even further in this sad new world.

I enjoyed reading the piece and the comments. Thanks for the opportunity.

This topic is near and dear. To keep my comment brief I will minimize references to why and concentrate on what. My father, born in 1911, dreamed of becoming a quantum physicist. 1929 put a stop to that dream. I was born in 1948 and was recruited by my father to live out his failed dream. I read Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn when I was eight and declared to my father that I wanted to become a writer like Mark Twain. His response was “You’ll never make a living doing that!”. Naturally, I read the subtext that if I wanted the small dribbles of affection and attention to continue I would continue to be daddy’s little scientist. While a senior in high school I was reading Goethe and came across his critique if science based on objects and properties was not only wrong, it was an evil pact with the devil. I matriculated at Illinois Institute of Technology in the fall of 1966. I dropped out when I realized I had nothing much in common with physicists other than strong skills in mathematics. I also had a long cry when I realized I had been abused psychologically by my father. I planned to go back to my nine year old’s dream to write novels but the voice of Goethe whispered in my ear that I was uniquely qualified to attack the pseudophilosophy of mechanistic materialism. I heeded that call and returned to IIT as a math major thinking that the ineffability that I had read about in the Upanishads and Gödel’s incompleteness theorem would do the trick. I was treated like a rank fool so I decided I would go for a PhD in mathematics at Claremont Graduate School. That was from 1982 to 1989. When I realized if I were to become the most famous(among mathematicians and physicists) mathematician in the world, I would still be treated as a crazy. I left Claremont ABD with an MSc. Since then I have pursued a path that I eventually accepted being classified as a philosophical journalist. In 2015, I was auditing a graduate class in Daoism taught by Roger T. Ames, a world class sinologist, and a fellow student loaned me a copy of “The Master and his Emissary” by Iain M Gilchrist. Finally, I had found someone who not only understood my point of view but had mountains of scientific evidence to back it up. A warrior to defend the humanities in the culture wars of C. P. Snow had arrived. He has had an uphill battle but he looks more and more like he will vanquish the visigoths of the STEM crowd, namely the reductionist materialists. This was a battle that I felt all my life I had to fight because I had such a deep understanding of the mathematics of the physical sciences. Lately, I am working on wordless poems using music and animation software. I also have more than a few ideas on writing. Last year, I discovered David Whyte and am getting back into poetry. I am leaving the culture wars to Dr. McGilchrist and his able followers. The arts and humanities people have to wake up and realize that Sheldon Cooper and his followers are going to kill us all. We arts and humanities people are the last hope for humanity. We really need to wake up and get our collective shit together. A good start would be to burn all the crap from postmodernism.

Thanks for your very personal report, Charles, quite edifying. I shall have to Wiki this Dr. McGilchrist, and Sheldon Cooper.

Robert Burns didn’t actually write “The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry.” He wrote “The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men / Gang aft a-gley”. May not matter much of course — after all it’s only humanities!

I can’t believe you’re not right though that the study of English literature as well as the humanities in general will regain popularity as that pendulum swings back.

No one’s mentioned capitalism…?

Since the 60s, government funding for higher ed has steadily declined and the need for student loans has grown. As with the neoliberalization and its attendant privatization happening in other parts of society, universities and colleges increasingly resemble corporations. Tellingly, a lot of university admins refer to students as “customers,” “clients” or even (I sh*t you not) “assets.” Many public universities have restructured their budget models to adopt an RCM model. (This list is out of date— Oregon State made the switch in 2018, with virtually NO protest from those in humanities and social science programs— but it’ll give you an idea of the shift that’s taking place: https://libguides.utoledo.edu/c.php?g=1101625&p=8253787) When higher ed is being run more and more as a neoliberal capitalist enterprise, it seems inevitable that programs that can’t hold their own under such models are viewed as dispensable, as “negative investments.” I guess you could blame students’ choices to some extent, but it makes much more sense to me to blame everyone (not just the GOP, most Dems have heartily supported neoliberalization too) who’s voted for decentralization, reduced funding for public education at all levels, and privatization across sectors (including education). I also blame all of the tenured and tenure-track profs who sat idley by or didn’t do anything besides fret and wring their hands when such neoliberal shifts worsened at their own schools. Especially in programs like Gender Studies, Black Studies, Native Studies, and Queer Studies, all of them had themselves intimately studied (if not written articles and books about) this very phenomenon, yet took virtually no meaningful action to stop it from happening at their own schools. To be blunt, it’s because many of them are cowards who are only concerned with their own job security. Capitalism strikes again.