Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Rebecca Lawrence. Rebecca is Managing Director of F1000. She was responsible for the launch of F1000Research in 2013 and has led the launch of many funder- and institution-based publishing platforms partnering with the EC, the Gates Foundation, Wellcome and others, that aim to provide a new trajectory in the way scientific findings are communicated.

Ten years ago, when we launched the open research publishing venue F1000Research, scholarly publishing approaches and practices to support open research were a universe away from where we are now. When I think back to the conversations that we had a decade ago, many of the reservations we encountered have today dropped away, and open and transparent ways to share and validate research are becoming much more commonplace: for example, the requirement for authors to share their data openly as part of the publishing process, and for peer reviewers to provide their reviews in full and transparently. Adoption of more open research approaches to publishing has of course been accelerated by the leadership and policy imperatives provided by a number of leading funding agencies and research institutions, perhaps most recently exemplified in the UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science, and NASA’s Transform to Open Science initiative and the OSTP’s launch of 2023 as the Year of Open Science.

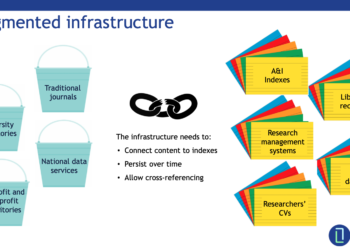

Importantly, enabling open research to flourish and deliver its promise and bring efficiencies to (and impact from) our collective research system requires connections across all aspects of the system. For a start, the outputs and products of research need to be discoverable and usable. Whilst over the last ten years there has been massive progress in the ability and speed in which we can get new findings out – through journals, platforms, and preprint servers – there remains much to do to connect all the pieces and build a knowledge base that can serve as the springboard to more rapid discovery and human progress.

Keeping interoperability simple

We all know that the pressures on researchers’ time are increasing; requirements that can enable open research (e.g., depositing research data in open repositories; publishing research open access) can run the risk of adding to those time pressures despite best intentions. Funders, research institutions, and publishers are increasingly bringing in their own specific policies around open research, but we have a duty to make the ability to comply with those policies as easy and simple as possible. Furthermore, without proper incentives and support for researchers to understand why those polices are there, and then how to adhere to them, any extra burden is seen simply as a detractor from the time that could be spent doing research in the first place. One way to improve this is to facilitate better connectivity across the research ecosystem: between researchers, their institutions, their funders, and with the myriad of research inputs and outputs. This is why unique and persistent digital identifiers (PIDs) and associated research descriptors and metadata, are so fundamental to making open research effective.

In our work with funders such as Wellcome, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the European Commission, it is part of a deliberate strategy to ensure that the publishing services we provide are embedded into the research lifecycle and designed to facilitate open research. Like a growing number of publishers, all our publishing venues provide functionality to capture key researcher and research descriptors during the publishing process (e.g., ORCIDidentifiers for authors and reviewers, full grant details, contributor roles, DOIs for underpinning data sets and for reviewer reports).

We try to make it easy for our authors – providing integrated links, drop-down lists, and APIs to other websites – but there is always more to do to keep the author journey simple. Where possible, we use commonly agreed and community-led research descriptors and standards, so following the lead of DOI providers for content such as Datacite and Crossref, using ORCID identifiers, and looking to organizations such as NISO for other ANSI-approved standards such as CRediT. Across publishers, use of common approaches when implementing such standards, and describing the requirements and benefits of providing research descriptors are key to ensuring good uptake. Further collaboration is also required to improve the quality of some PIDs in the system so that we get better value and greater efficiency gains from their use.

Ten years ago, I would also have anticipated that tools like ORCID would by now be commonly used to auto-populate grant applications, tenure applications, and in publication submission systems. Greater use of this and other PIDs would also greatly assist in managing author payments and publishing agreements. There has been some progress. For example, some funding agencies now include ORCID integration into their grant management systems (e.g., Swiss National Science Foundation, Luxembourg National Research Fund, Wellcome) and assign a DOI to their grants via Crossref. Some agencies are using standard application forms and CV formats for various purposes (e.g., NIH’s SciENcv project and the UKRI’s Resume for Research and Innovation). And it is especially pleasing to see recognition in the OSTP Nelson Memo of the importance of sharing key metadata and associated PIDs. However, the ability to automatically pull details of a researcher’s work when submitting a grant application, for example, is still rare. If we were to do a better job of capturing, connecting, and then pulling through PIDs in all directions, right from grant stage to the range of researcher outputs, we would be able to far better enable the full value of their use.

The question remains, why have we not achieved more in delivering connectivity across the research system? While funding for this kind of underpinning infrastructure is notable in its absence (or where it is available it is often too temporary in nature), the other major challenge is in securing adoption among the service providers (funders, publishers, and institutions among the key players) that would maximize the use and potential of building those connections. It is notoriously hard for organisations to tweak or adapt existing workflows and legacy systems and to demonstrate the benefits (and hence prioritise the work) at an individual organisation level that may seem obvious at a system level. This is an industry and sector-wide challenge.

Reminding ourselves why this matters

As part of efforts to improve research culture, many research organizations and funders are developing new ways to evaluate research and researchers. The focus of reform in most research assessment systems is to move away from a focus on journal-based and largely quantitative metrics as proxies for research quality, toward a broader focus on the contributions of researchers to a wider range of activities that add value to the job of delivering research and impact – and which are every bit as important as publishing in a journal. This is the essence of the Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) which was also founded 10 years ago in 2013, and this is also at the core of the recent CoARA and HELIOS initiatives, amongst others. By enabling researchers to publish, make discoverable, and connect a wide range of their research outputs and insights through the foundations of common descriptors and identifiers, scholarly publishers and other actors in the research system can make possible the shift to a more inclusive and holistic research system.

As the ability to share different types and formats of research expands, embedding standard research descriptors and identifiers around key research inputs and outputs is going to become increasingly crucial to fulfil the promise of open research and to ensure the discoverability and connections between pieces of research. We don’t need to adopt the same systems or workflows, and there are a growing range of research descriptors and identifiers out there often designed for specific purposes (e.g. Research Activity Identifier (RaID) used in Australia), but by committing to embed commonly agreed identifiers into our workflows, this will lay the foundations for the connections across our research system to be made.

We are in the midst of a knowledge production revolution precipitated by technology and more rapid and efficient ways of working. With the further development of technology and the potential of artificial intelligence to bring efficiencies and make connections across our research corpus, the need to present that corpus in the most useable way becomes an imperative. Open research is not a threat to the scholarly publishing industry, it is the opportunity to refine, evolve, and reinvent what we do so well in order to validate, curate, and deliver research in the best possible way to help maximize its impact, which is what our industry is about.

Over the next ten years, for open research to flourish and achieve its promise for the benefit of all, requires: a) shifts in research culture and how we incentivize and reward the types of behaviors that will deliver the knowledge and progress we need; b) collaboration between research teams, communities, stakeholders, and nations; and c) further commitment to building a much more connected research ecosystem. I hope we see an increasing commitment from stakeholders across the ecosystem to work collaboratively and in partnership to support those that are making the knowledge, to help them spend as much time as possible on actually conducting research, and to then maximize the impact of their work for the benefit of us all.

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Why Interoperability Matters for Open Research – And More than Ever"

Thanks for your post Rebecca! I couldn’t agree more. From my perspective as the program leader for the ORCID US Community consortium, I think one big way that all organizations in the scholarly communication ecosystem can help is to actively write information to researchers’ ORCID records (using the ORCID Member API). That way when organizations try to pull information out of ORCID records, or when researchers try to populate their grant applications and other forms using ORCID, there is actually information there to be shared/re-used.

“Keeping interoperability simple” is a crucial principle in today’s world of complex. By focusing on simplicity and standardization, we can ensure that different devices, platforms, and software applications can communicate with each other seamlessly. This not only improves efficiency and reduces costs, but also enhances user experience and promotes innovation. So, let’s strive to keep things simple and compatible, for a better and more connected future.