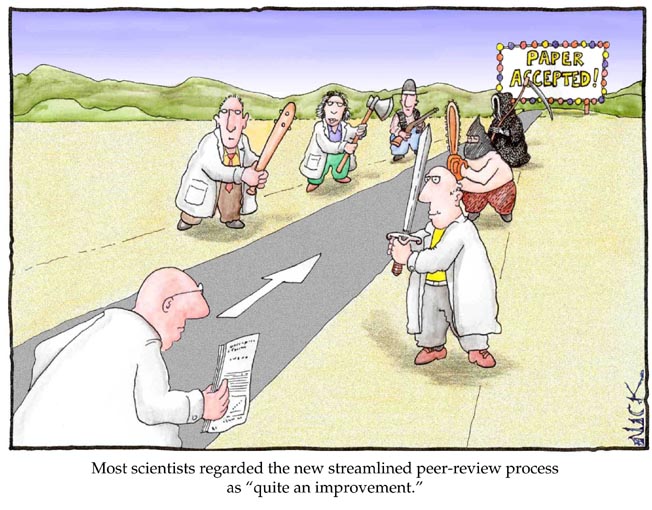

When I searched Google Scholar for “improving peer review” I got 16,800 results (and I only included items published since 2014). Searching The Scholarly Kitchen for “peer review” I found that there were 40 results dated 2009 or later. Adding my own informal discussions with publishers as well as scientific and medical authors and researchers, it seems pretty clear that article review and submission processes are on the minds of all participants and that experiments underway.

So this month we asked the Chefs: How can we improve the article review and submission process?

Joe Esposito: I hate to be a contrarian, but the right question is not how to improve the submission and review process but for whom is the process being improved? The answer here is obvious: the only player in this system that drives decisions is the one that invests capital, and that means the publisher. Improving the system has to have a benefit for the publisher or it won’t happen. In this formulation improving the process for authors and reviewers is best understood if it provides a return to the publisher. Will a more efficient system persuade more authors to submit papers to a particular publisher? That’s a reason to invest. Will it reduce costs? That is a reason to invest. But it should be clear that all such improvements are an arms race: when one publisher does this, all the others must follow.

So rather than thinking about the process or the system, let’s think about this question in the context of the marketplace reality we must work with.

David Smith: Sixteen years ago now, I ran a peer review process where our average time to first response was less than eight weeks. Total elapsed time, not working weeks. I once hassled an Australian reviewer in a pub in Melbourne for his opinion (virtually; via the phone – they wouldn’t fly me out there, alas). So if time is really a problem I venture to suggest that “it ain’t rocket science, get yer process sorted out!”

But the mechanics of the submission process for the author could be very much improved. Why do we insist on formatted citations? DOI links would be better all around in as many places as possible would they not? Give them a Dropbox folder (per article) to enable easy sharing to us of the material for publication. Clear out the stylesheet anachronisms; make the submitted article format something that is easy for time short reviewers to get to grips with (there’s that Dropbox folder again…); ORCIDS to save time on boring administrata; login using Facebook or Google (Or cough, ORCID, cough). Regard the author as a purchaser and our process(es) as a shopping cart funnel and apply the same type of focus on maximizing the throughput to the ‘checkout’.

Charlie Rapple: From public acknowledgement for reviewers (for example, Publons) to never-ending review (such as PubPeer), it’s clear that experiments around the review process are gaining traction – such start-ups are both growing (Publons is about to open a second office) and making a meaningful contribution (PubPeer has helped to expose flaws in several papers that have then been retracted).

Is there as much disruption happening around submission? One challenge I’m considering is how we can better capture and surface information that is currently lost in the submission process. For example, many journals ask for highlights, key findings, implications, publicity/outreach summaries, statements of novelty and so on as part of the submission process, to assist editorial triage and review. Often, this information is never published alongside the article. Why not? Outdated or inflexible publication formats, systems or workflows? The unpolished nature of the material? A lack of clarity about who it is aimed at? I’m curious as to what might prevent this information from surfacing – and also, curious to learn of examples where this kind of information has successfully been made public, and to what effect.

Alice Meadows: While peer review may have its detractors, survey after survey shows that most researchers continue to trust it and see it as central to the scientific process. That’s not to say the current system is perfect, of course – which system is? But hopefully, through experimentation with different forms of peer review – pre- and post-publication – it will continue to improve.

In the meantime, the one thing I believe would most improve the submission and review process is better education and training. At present, this is virtually non-existent, at least in any consistent or comprehensive way. Individual PIs and professors may teach their students, many publishers and societies offer in-person or online training, and organizations like Sense About Science also provide support – but there are still way too many reviewers and authors who have never received any formal training at all. And it’s starting to show – especially with the emergence of new players such as China, which is set to overtake the US shortly in terms of article authorship. As the authors of this Chronicle article on peer review point out, “The emergence of world-class universities creates the potential for China to become a vastly influential part of the higher-education landscape. We should all care whether the academic work being done there meets a standard that scholars in the United States—and around the world—can trust and build upon.” Surely this is something that the global scholarly communications community, collectively, can and should help with?

Michael Clarke: The main problem with the review process is that it often has to be redone. Papers not accepted at Journal A have to be re-reviewed by Journal B and sometimes Journals C and D. This is incredibly inefficient and results in higher than necessary system costs (if we think of the scientific publishing process as a system). It is true that authors often revise papers between submissions and that many times the authors don’t necessarily want Journal B to know that the paper was previously submitted to Journal A.

There are also many cases where the paper is very good but Journal A just couldn’t publish it due to its scope or limitations on how much they can accept. Publishers are increasingly building internal peer review cascades for papers in this category, but that only works if Journal A and Journal B are published by the same house. Might there be a better approach? A way to cascade between publishers? And a “common app” approach to paper formatting so that papers don’t have to be re-formatted between submissions? Publishers have worked hard over the last decade to streamline the submission process and reduce the time from submission to publication, but this does not address the issue that causes the largest delay, which is having to reformat and resubmit papers to multiple journals.

Phill Jones: Journal submission systems have a terrible reputation among researchers. As a former researcher, I could rant all day about them, but I’ll restrain myself and pick one aspect. People complain about slow upload speeds and poorly designed workflows that mean they have to babysit a submission for several hours.

For example, if a submission includes 10 files, including cover letter and high-res figures, it takes 5 minutes to upload each file, and you require input from the user afterwards to complete the submission, you’re going to end up with some pretty frustrated authors. We used to have a situation where authors just put up with that sort of thing, but in these days of author charges, researchers are beginning to expect service for their money. My advice would be for publishers to try out their submission systems themselves (under realistic conditions, with large files and multiple authors) and see how much of a pain they are to use. If you do this, you’ll probably see some easy wins.

There are a number of people working on solutions for Google docs-like cloud based collaborative writing solutions. Systems like this could work with publisher templates, making life easy for authors and reducing submission check cost. The goal is to plug directly into review systems for seamless authoring, submission and review.

Peer-review is the worst form of academic quality control, apart from all the others. I’ll leave that to one of my fellow Chefs to worry about.

Angela Cochran: Ah, manuscript submission…the necessary task of jumping through unnecessary hoops. Publishers can make the submission process easier by reviewing their laundry list of requirements at least once a year. I bet there is something you could live without. For example, most of our accepted papers go through at least two versions. This affords us the luxury of not needing final figure files and other pieces at the time of submission. On that note, check in with the production folks every now and then. The submission instructions may include formatting or file requirements that are no longer necessary in the production process.

Submission systems could be a little more proactive about making the systems user friendly. It feels like most improvements make the editorial office users happy (makes sense seeing as they pay for the service) but we also need for the author users to be happy. Let’s not ignore the look and feel of the interface.

The single greatest problem for editors with the review process is finding good reviewers. More and more, I hear complaints about inadequate reviews or invited reviewers ignoring deadlines. We have not found a cost-effective and efficient way to solve this problem. The reviewers and editors also report that a good chunk of authors are not adequately responding to reviewer comments. We try to make it clear to authors that they don’t have to agree with all the requested changes but they should address in their response to reviewers why they aren’t going to make the changes requested.

I asked our editorial coordinators, those on the front lines of author and reviewer queries, what they thought. “To the researchers that work through us, our process is often a trudge across a bog of unwieldy software and cursory guidelines…we become a speed bump between research and dissemination. We must strive to be unobtrusive: progress updates need to be transparent, password retrieval a cinch, requirements visible from miles around,” said Nick Violette.

Jennifer Chapman offered the following: “These processes can be improved when we walk in the footsteps of either the reviewer or the author. By knowing how each step works without error or complication, we can then begin to make the process user friendly with a limited number of steps. Ease of process is key.”

Lastly, we must always remember that being an author is a very small part of what our authors do each day. We should try not to make this difficult for them.

Judy Luther: Peer review is often in the news with either ideas about accelerating the existing workflow with an incentive for reviewers or an innovative approach to post publication peer review in a more open environment. Since PLOS ONE distinguished between reviewing for quality but not for significance, different configurations have evolved leading to a more open review process.

As a result researchers have access to an increasing array of options for public comment, discourse or a review that enables communication online that may not be occurring offline. At least two initiatives are seeking to provide an incentive for researchers to participate by recognizing their peer review activities. ORCID is collaborating with CASRAI, the Consortia Advancing Standards in Research Administration Information to acknowledge peer review activities. Publons is launching a new service to showcase peer review activity.

Researchers are clearly identified on ResearchGate which introduced Open Review, a structured mini review with sections for methodology, analyses, references, findings and conclusions. One of the first posts described failed attempts to replicate a study casting doubt on the validity of the original paper. Since it is difficult to publish negative results, an open review environment can serve to provide a more complete view.

Somewhat controversial, PubPeer is a site allowing anonymous posts that serve the whistleblower role. Its blog lists articles that were withdrawn or retracted as a result of issues raised on its site. It is currently facing a lawsuit that may affect its future.

Core to journal publishing is the creation of the scholarly record to document results for future reference. However, peer review is not necessarily effective in catching author misconduct and cannot be expected to validate research results. Retractions due to author misconduct are on the rise and the most notorious cases have rocked their disciplines because authors who fabricated data went undetected for years without their results being questioned. Although it comes with challenges one of the advantages of the open peer review environment is that it serves as a vehicle that could improve the scholarly record.

Phil Davis: Submission fees. The submission process is a matching market in which the submitting author makes a calculation based on the likelihood that his/her manuscript will be accepted. Before online submission systems, authors had to pay several costs in the submission process: the cost of printing several manuscript copies; the cost of shipping a bulky package of these manuscripts to the editor; but mostly, authors had to pay with their time. Online submission systems severely reduced (or eliminated) many of these costs to the author. The result–a growing flood of poorly matched manuscript submissions–should not be a surprise. In addition, internal manuscript transfers (also known as peer review cascades), may further encourage authors to select inappropriate journals for their first choice, knowing that, if rejected, the manuscript may be transferred to the next journal in line. If journals are not willing to make expecting authors wait (most journals wish to reduce their time to first decision statistic), they must consider other ways to encourage good selection choices. A submission fee–even a small one–may incentivize better submission decisions.

______________________

Now it’s your turn.

How do you feel we can improve article submission and review processes? What has your organization done in this area?

We look forward to hearing from you!

Discussion

49 Thoughts on "Ask The Chefs: How Can We Improve the Article Review and Submission Process?"

When I search Google Scholar for the exact phrase “improving peer review” anywhere in the article, since 2009, I only get 134 results. Searching for all time gives 295 hits. Your results must be for searching for the mere occurrence of all of the three words “improving” and “peer” and “review”. Such articles need have nothing to do with improving peer review. While there is in fact a scholarly literature on improving peer review, I think it is small. I happen to be doing research on this at the present time, especially the issue of “pal review.” The question is what research we might be doing and how to do it? There is a lot of talk about improving peer review but very little research.

Happy to see such unanimous consensus on the things that can be fixed! Not too long ago, the most common response to any suggestion on improving these things was nonchalant “if it’s not broken, don’t fix it”…

Peerage of Science has been doing a lot to address many of these issues, and largely along just the lines suggested in many of the chefs’ responses (full disclosure: I am the founder of the company).

For example, the single set of (cross-reviewer scored) peer reviews in the service can be used by a large number of journals (https://www.peerageofscience.org/journals/), and authors are free to give link giving access to those even for editors of non-participating journals (whether editors want to use the link is up to them).

If I had to name ONE thing that would have the biggest impact on improving academic publishing across the board, it is this:

Please have the courage to say out loud that the quality of peer reviews (yes, even those solicited by the eminent infallibe editor of your highly prestigious journal) varies, and then act accordingly.

Lots of good ideas here. From my viewpoint as a former Editor-in-Chief, Alice Meadows goes to the heart of the matter. Want to sail through submittal and review? Write good papers! Concise, focused manuscripts, written in clear, straightforward standard English (c.f. Hemingway, E.), bring out the best in reviewers.

I’ve seen too many papers where the author clearly lacked mentoring. Inexperienced researchers, for example, tend to overemphasize minor details while taking for granted important assumptions. Reviewers sense these weaknesses, and a torrent of comments follows.

Indeed Ken, lacking research it is unclear how many of these perceived problems really exist, or to what degree. Peer review is an intrinsically complex process, involving millions of reviews every year. No one sees what the others are doing so it is easy to think that there are hidden problems, which may not exist. This is normal in complex organizations.

Nice interview.

I´d like to highlight the creation of databases of reviewers where authors and publishers can have their manuscripts reviewed and reviewers can be compensated without damaging the independence of journals. We´ve had some positive experience with the recently created database http://peereviewers.com

Do you know of some other database for biomedical journals we can try to compare?

Thanks!

Over the last few weeks I’ve spent a great deal of time reading, researching and thinking about the peer review process in anticipation of talking to our graduate students about scholarly publishing and peer review in particular. The voice of those emerging authors is seldom heard or considered so I thought I would share the questions and issues the students in my session had about the process: why can’t I ask for a double-blind review?; if reviewers know my name will my work be discounted because my name is obviously female?; what if I find significant new information while the paper is under review?; am I allowed to say ‘no’ to suggestions/comments made in the review?; how long will it take?; why is there so little guidance for publishing in the humanities when articles on STM are common?; why do people agree to be reviewers?; how do I learn how to review?; and, can I trust the review to be fair? Perhaps one way of improving the process is to consider those gaps and provide answers.

These are all great questions. Thanks for sharing them. I will note that for the most part, these are not questions or complaints about the actual submission process. The first two questions are really hard to address–unless you are an organization willing to jump head first into double-blind review. Allowing some papers to follow one process while others follow another is not a simple task, but perhaps it is time to figure that out.

Questions about what is allowed and not allowed in the review process may be handled in the author instructions, which I know people are loathe to actually read. But also, editors are people and they often write papers as well. Authors should always feel that they can ask editors for advice if there is new information to be added or certainly if a mistake is discovered.

The place to learn to be a reviewer used to be in your graduate program. Your adviser may give you papers to review and provide feedback. It seems that less of this is happening. At a recent editorial board meeting held at a technical conference, several students wanted to sit in on the meeting. It struck me there that we should include sessions on how to review papers at these technical conferences that already attract so many students.

Authors also need to do a better job of being authors. We have seen an increase in authors wanting to add new authors halfway through the process because they “forgot” to include someone. We also have seen an increase in excessive changes being made in the page proof stage. This assures you a one-way ticket back to the review process. Lastly, we have seen a huge increase in the number of authors who simply ignore reviewer comments when they return a revision. Again, they don’t have to agree with the change requested, but they should address that in the response to reviewer comments.

I know a few research societies that have created programs to help train peer reviewers. This is increasingly an area where a society can offer a valuable service to members. Here’s an example from the Gerontological Society of America:

http://www.oxfordjournals.org/our_journals/geront/for_authors/general.html#New%20Professionals/New%20Reviewers

One of the best ways to become a better author is to volunteer for a term as an associate editor. Forced to evaluate reviews and reconcile author responses, one can’t help but learn what works and does not work!

I also think the authors need to do a better job at being reviewers. They should accept review assignments more frequently from journals they submit to and provide thoughtful, efficient reviews. Would they not expect the same for their own papers? It’s a cycle that many authors ignore.

REVERSAL OF EDITORIAL DECISIONS. The Committee on Publication Ethics has a “Code of Conduct and Best Practice Guidelines for Journal Editors.” I was pleased to see:

3.2. Editors should not reverse decisions to accept submissions unless serious problems are identified with the submission.

3.3. New editors should not overturn decisions to publish submissions made by the previous editor unless serious problems are identified.

The importance of this cannot be over-emphasized. When an editor says a paper is accepted, he/she should mean it. This is not a minor issue, since once an author has a formal acceptance he/she designates the paper as “in press” and those who evaluate (e.g. granting agencies) assume that it is as good as published. Sometimes, they even ask to see the letter of acceptance. Yet, twice in my professional career I have received formal, unconditional, notices of acceptance, and subsequently Editors have backtracked without reason (bland comments like difficulty scheduling, that do not really constitute reasons).

The first was in the 1980s by a leading medical journal and I then had the papers published in Medical Hypothesis. It seems there was an editorial change and the new editor did not like what the previous editor had approved. I thought this was just a blip, but recently I had the same experience with a widely known US journal. A senior editor formally accepted my article and gave likely publication dates, asking me to make myself available to check proofs. When the acceptance was suddenly reversed I appealed over the editor’s head to the publisher, but got no response. Again, it appears that there was a change in editorship and the new editor did not approve.

The situation might be better if more publishers declared their support for the CUPE guidelines.

Joe Esposito’s response is particularly interesting when viewed from the OA perspective. Gold/Green OA publishers have fewer resources and incentives to orchestrate an effective peer review process.

Consequently, members of promotion and tenure committees who depend upon the assumption that publication indicates a positive peer assessment may assign a lower value to OA publications.

Yes, this is happening. There is still an attitude among certain disciplines that an online only OA journal is less rigorous and therefore not as important. I can’t actually argue with that when there are huge OA journals doing “peer-review lite”. It is less rigorous…that’s the main selling point to the paying authors! I suspect that this is why there is so much emphasis on alternative metrics from the OA community. When you can say that X number of people “read” (more likely viewed) your article or tweeted (not necessarily read or used) your article, you can try to counter-balance these attitudes. However, the polish is coming off of that one as people become more and more skeptical of the metrics being used.

David, can you say anything further about the prospect of using ORCID as a sort of social login? Seems that could have appeal going far beyond just article submission and review.

Note that the RCUK is proposing that use of ORCID be a requirement for all researchers they fund:

http://www.rcuk.ac.uk/media/news/openaccess/

Good to have further mechanisms to roll it out as an identifier. Turning it into a cross-platform social login account is a step further that, unless I’ve missed something, hasn’t been announced.

Hi there David And Roger,

I’ve always thought that if you go to all the trouble of a sorting out a person identifier such as ORCID, it would be rather marvelous if you could push the utility as far as possible. If there was a near universal method of allowing a user to sign in to our various services and us to be able to correlate their parent institution to a subscription data, then whether it’s a mobile device, or a coffeehouse or a location we don’t know about, it simply doesn’t matter we can allow access. No it’s not on the ORCID a development path, but I think it’s fundamentally a solid idea and one that would solve a lot of issues for both publishers and users of our various wares. IF RCUK are mandating it… 🙂 then in the UK at least, pretty soon we’d have a good set of data for such an access system. Also, one that resides in the hands of a trusted 3rd party.

Anybody else think it’s a good idea?

I have been writing a bit recently urging the benefits of a universal sign-on (http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2015/02/05/data-for-discovery/) and (http://sr.ithaka.org/blog-individual/meeting-researchers-where-they-start-streamlining-access-scholarly-resources), so I am 100% with you on that. ORCID’s weakness, I suppose, is that it would cover authors better than non-authors such as students who would also benefit from a kind of social sign-on. But perhaps ORCID could expand from its base.

Thanks for an informative post, Ann. Here is my take on what is wrong with peer review and submission processes:

• Authors having to put aside half to one day and roll their sleeves up in order to submit a manuscript. And in this day and age authors or editors should not have to read manuals to use online systems. (When was the last time you read a manual on how to use Amazon or FaceBook? Those are far more complex than a peer review system!)

• Tedious author instructions, mostly unchanged for years or decades on how to format a paper, including punctuations in references. Mostly similar but all slightly different in order to distinguish them from the rest. This is tortuous for the author who think they are making the job of the publisher easier. Unbeknown to them, they are completely wasting their time. As a typesetter for 25 years, I know that we dump all that careful formatting, create XML, then create the correct format again with a filter. We are in the blogging age, and with a little development, the blogging model is almost perfect for writing and submitting files, rather than attaching dumb Word files. Let go of attachments, guys!

• Pre-publication peer review, taking months to accept or reject, while good science stays hidden.

• Anonymous peer review – an argument I have heard for this again and again is that young researchers fear “retribution” from seniors if they criticize. I cannot believe we just accept this state of affairs. Bit like saying there is a bully in the room so we’ll all hide under the table. Let’s stand up, name ourselves and beat the bullies instead!

So my ideal scenario:

• Online authoring system structuring content automatically

• Immediate Open Access publication, good, bad or quack

• Open, post-publication peer review

• Content delivered in any format to reader

I would suggest that if peer review is only faulty in relation to wish lists like this then there is actually nothing wrong with it.

• Anonymous peer review – an argument I have heard for this again and again is that young researchers fear “retribution” from seniors if they criticize. I cannot believe we just accept this state of affairs. Bit like saying there is a bully in the room so we’ll all hide under the table. Let’s stand up, name ourselves and beat the bullies instead!

How, exactly would you propose to do this? It strikes me that this is simply human nature, particularly in an environment where there are limited numbers of jobs and limited amounts of funding. There are so many undetectable ways a powerful researcher could derail the career of someone they felt had unfairly criticized their work, simple things like subtly being unenthusiastic about a grant application in a study section, or not recommending someone strongly for a job. I know Nobel Prize winners who are notorious for destroying anyone who dared to compete with them. How would you prevent that from happening?

I suspect the only ways to truly achieve this would be to take humans out of the decision making process altogether or perhaps to change the structure of the research career away from selecting for those who best make discoveries and toward those who are nice to their coworkers. Neither seems particularly realistic.

I just find it hard to sit back and accept that human nature is to “derail careers” and Nobel Prize winners are known for “destroying anyone who dared to compete with them”. Perhaps our research system puts too much emphasis on ruthless competition, rather than collaboration.

Sadly this is the nature of some humans (not a case of universal human nature). And sadly it seems a fair number of those (again not all) driven to succeed also have a drive to prevent others competing in their playground.

Those that succeed achieve power. Those that succeed and are nasty then abuse this power. it happens. In all aspects of life. In science, in humanities, in business, in school, on sports pitches.

We can’t have systems that presume humans always act with a angel on their shoulders when too often it’s the devil at the wheel. People get run over and crushed that way, as David states.

As a species we are both inherently collaborative and inherently competitive. The balance in individuals and in systems is always changing and rarely, if ever, in equilibrium. Again the systems we devise should be aware of this.

And they will fail if they have humans involved as humans are fallible. This is why transparency and routes of appeal, preferably to independent arbiters, are also crucial in designing new systems.

It’s a nice idea, but our research system is entirely built on competition (and has worked fairly well over the years). You have a limited amount of funding and a limited amount of jobs, along with an enormous overabundance of graduate students admitted to the system and granted PhDs. Do you set up a system to reward accomplishment or to reward friendliness? Which would result in more progress? Would you sacrifice the benefits that have come from the discoveries of those Nobel Prize winners and replace them with the warm feelings that might have come from lesser scientists who were kinder to their colleagues?

“Worked fairly well”? Relative to what? That a train is moving ahead at 20 miles an hour seems fine, unless one knows trains are capable of much faster speeds. And a system that rewards both accomplishment and friendliness has been on the table for decades. I have even written a book on it!

“Worked fairly well” in terms of improvements in technology and medical treatments, new drugs, increased survival rates for diseases, better knowledge of our universe, etc. Are you seriously suggesting that we should award our precious and seemingly dwindling research funding to people who seem nice, rather than people with good ideas? Can you name any other industry where friendliness is rewarded over results?

I don’t think you can use a vague idea of “worked fairly well” as an argument. In the same vein I would not use a vague idea of “worked pretty bad” (because it did not solve malaria, got a generation addicted to Ritalin, gave us cluster bombs and for billions of useless medical treatments). The question here is: what would we loose and gain by making peer review post and non-anonymous and open?

Well, I did qualify it as “fairly well” rather than “perfect”. But you’re suggesting throwing out a system that has proven successful, at least on some level (we do seem to have new technologies and health improvements for example) and replacing it with one that is entirely unproven. Seems to me that things are going as they should–there’s plenty of experimentation going on with things like open and post-pub peer review and we’ll see how useful they are. That makes a lot more sense than wholesale changes before collecting that evidence.

The question here is: what would we loose and gain by making peer review post and non-anonymous and open?

Open:

The first thing lost would be the freedom to speak truth to power. If you look at journals that allow reviewers the choice of signing their reviews, they almost never sign their names to negative reviews. By allowing anonymity, we let the less powerful criticize the powerful without fear of retribution. Because research is done by humans, human nature and failings will always play some role. There will always be some researchers looking to retaliate against slights or to protect their turf from others. Anonymity allows some protection against this.

Post-Pub:

Nothing wrong with Post-Pub peer review, but it should be seen as a supplement to Pre-Pub. More filters are better than fewer filters. I have yet to meet a researcher with lots of spare time who wants to read more papers. Every opportunity we can offer for filtering the literature and offering the reader voluntary cues to help prioritize their reading, the better. A good article on the specific values offered is here:

http://serialmentor.com/blog/2013/12/21/the-value-of-pre-publication-peer-review

Why should one require the elimination of the other?

Peer reviewers are NOT anonymous to the Editor. I had no hesitation taking to task any (rare) reviewer offering mean-spirited or unprofessional comments. I also would advise an author if a reviewer’s requested changes were unnecessary or wrong. The key is to have a moderated review process, not a free-for-all.

Wikipedia is by definition the most anarchic “free for all”. But the contents are probably more reliable than scholarly journals. I think we can look to something similar to disseminate modern science rather than patting ourselves on the back for continuing a system largely unchanged since its inception 350 years ago!

There is almost nothing in that statement that is true. Scholarly publishing has changed dramatically in the past ten years, not to mention the past 300. No one who has ever read the Wikipedia at length will agree with the idea that it is a better guide to quality than peer-reviewed material.

I’m not sure I’d define Wikipedia as a “free for all”. It was originally set up to be that way, but over time has evolved into a highly ordered hierarchy, with an elite cadre of a small number of editors who carefully control the vast majority of what gets added and what gets changed. Nature apparently abhors a vacuum.

I’d also dispute the notion that Wikipedia contents are “more reliable” than those found in scholarly journals. I’ll put our retraction rates up against the rates at which edits are made in Wikipedia any day of the week.

This is surely apples and oranges. What is the use of comparing retractions with edits. You are surely right that wikipedia is a (special kind of) hierarchy, but still anyone can start or edit almost any page. I suppose Kavek made the reference to Wikipedia because some aspects of its model (open, distributed, free, retracable, fast) may have some lessons for current mainstream scholarly publishing.

BTW if you want an indicator for reliability of science I would not use retractions but reproducability ….

Jeroen – Looks like the “thumbs up” feature is gone on this post – so I’ll give you my thumbs up publicly (instead anonymously)!

I agree the comparison is a complete stretch, but then again, I wasn’t the one who tried to equate Wikipedia and journals. Both serve very different purposes and their design reflects those purposes. However, an unsupported statement that Wikipedia is “more reliable” than journals seems even more of a stretch. Taken for their purposes, I’d argue that journals are a more accurate representation of the historical record of particular sets of experiments/arguments than Wikipedia is an accurate representation of the world’s knowledge. Your mileage may vary.

Also interesting is seeing Google moving away from algorithms and crowdsourcing and toward editorial vetting of content:

http://www.theverge.com/2015/2/10/8010673/Google-health-data-knowledge-graph

Perhaps there are valid reasons that journals have been around for so long, and perhaps there are valuable processes that have evolved over that time.

Really enjoyed this post and the honest dialogue happening here in the comments. I’d like to highlight that ORCID SSO is a reality, and is already in use by more than 500 journals using Editorial Manager.

Full disclosure: I am Founder & Managing Director of PRE (Peer Review Evaluation) http://www.pre-val.org

The original post seems to address two distinct questions here:

1. How to improve the submission process for both authors and the editorial office

2. How to improve on peer review

I’m going to focus my response on areas most directly related to peer review.

There is a narrative that seems to be taking shape that open review is always good and anonymity in peer review is always bad. I find this to be a very myopic view of the peer review process. There is not, as yet, a single, minimum standard of peer review. Who knows when, if ever, there will be? Publishers and editors must use their best judgment to determine what level of rigor is appropriate for their journal and the scholarly community they serve

Many of the comments here relate to rewarding reviewers or facilitating post-publication peer review. I think there’s a bigger issue at stake and that is the efficacy of peer review itself. There is scant research around what review methodology (or methodologies) works best. Some will tell you that double-blind peer review is best. For others, open review is the ideal. I suspect that there are a dozen legitimate methodologies. But until we have evidence recommending one methodology over another, it’s just an opinion. More needs to be done to refine this process and, in my view, the first step is to make peer review more transparent. The more we can all see what’s happening today, the more prepared we’ll be to determine what tomorrow’s peer review process should look like. PRE-val could be a useful tool in this effort. It does not force publishers to conform to one peer review methodology. It simply opens the ‘black box’ of peer review so that editors, publishers, and the end users can see what process was employed for each article and they can decide for themselves if it was adequate for their purposes. Peer review is the cornerstone of scholarly communication and we all have a stake in improving and preserving it.

So, what to do?

If I had my way, all journals would make ORCID a requirement, not just for authors, but for all users that participate in the review process. They should not only accept ORCID identifiers in the manuscript submission process, but they should employ an OAuth protocol to collect the identifier. Why is this important? Look no further than the recent “peer review rings” which have led to retractions. Just today BMC announced 43 more retractions due to this. PRE is working with ORCID to address this by using mutual APIs to validate that those conducting review are who they claim to be. More on that soon.

Newer efforts are interesting and valuable, but they raise many questions we’re now being forced to consider: Who “owns” or has copyright related to a review? Some feel it’s the publisher/journal. Some feel the reviewer does. Others think the author does. I suspect all may be correct! There are very legitimate reasons why reviews should be kept confidential, but in the end I think this is a matter of journal policy. Getting reviewers credit for the work they do is important, but the editors and journals must be involved in this process. Posting reviews etc. without involving the journal is a slippery slope.

Training for peer reviewers. AMEN. Sense About Science is doing good work in this area, as are many journals and publishers. This is another area that PRE will be getting involved in.

To sum up: Increased transparency related to the review process, with the understanding that this means different things to different people; organizations need to work together and with the publishers on new initiatives for the benefit of all; ongoing education and training for editors, reviewers and authors. ABOVE ALL ethical behavior, honesty, and accountability for all those involved in the review process.

I do not endorse very much of this, Adam. You begin by saying that we have very little research to go on, to which I agree. But then you propose a laundry list of changes. So far as I can tell there is nothing systemically wrong with the roughly 6 million peer reviews of articles that happen every year. There are the expected aberrations, cheats and outliers but that seems to be about it.

As I said earlier, peer review is a complex process, involving millions of people, mostly volunteers. The total labor is probably in the hundreds of millions of annual hours and it is a highly distributed system, with no one in charge. It is completely focused on novelty, which creates a lot of time consuming looping in the message traffic. Given all this it may well be working as well as it can, and there is no viable alternative (sort of like democracy).

My fear is that we are simply seeing the “science is broken” movement at work. So far as I can tell, science is not broken.

David, I’m unclear what you don’t “endorse” since it seems we basically agree. Do you not think more transparency regarding peer review is bad? Do yo think using identifiers such as ORCID so we can make it harder for those who do spoil it for the majority is not a good idea? Do you think supporting journals/editors/reviewers who work hard to do the right thing is wrong?

Adam, my view after several years of research is that anonymous peer review is fundamental to the system and the system works well. Thus I see no need for so-called transparency and no clear role for identifiers. Note that in the policy realm “transparency” is often a code word for intrusion and coercion, if not control. If you want to use it you should make clear what you propose. Beyond that, I do not share the view that science is broken, which seems to me to be your starting point. Please consider the numbers that I presented, as they specify the context for this issue.

I certainly support those who do the right thing, so I have no idea what you mean by your last question. Do you think that anyone who does not support your particular venture favors wrongdoing?

David, the only thing that is clear to me at this point is that you have a complete misunderstanding of what I’ve said and what PRE services are intended to do. I’ve been very clear on how I’m using the word “transparency” but what was not clear, to me at least, was that you were using “code.” I’m not intent on using the SK forum to get into a personal debate. If you’d like to continue this conversation feel free to email or DM me directly.

From what I see of submission process, there is a lot to be desired. Some of the main problems, as I see it:

UX

Current submission systems treat the user as a data input robot. No care or attention is given to looking after the user.

Unstructured docs:

Most manuscripts (excluding those journals dominated by LaTeX) are unstructured documents. This leads to many problems:

* Programmatically mining those manuscripts for metadata to aid author (less data to input) is very difficult when the source data is unstructured

* metadata is often ‘copied and pasted’ from the manuscript and re-represented in the submission system leading to a duplication of data – which also leads to data being out of sync and there are multiple places to maintain

* there is no way to tell if a manuscript is actually being revised ‘right now’ and so chasing becomes problematic

* many submission systems do not enable an easy way to view diffs. This means that revisions need to be manually checked with the old version of the manuscript being open at the same time as the revised version. Very inefficient.

Programmatically validating data

Submissions systems could do very well to programmatically validate and enforce best practices for metadata and assets related to a manuscript. Figures, for example, should all be checked by machines, not humans, to validate publishing requirements etc. If the assets do not validate the article shouldn’t be able to be submitted.

Programmatically pre-populating metadata

Submission systems should be able to read data from a manuscript and pre-populate data (as per above). This data should contain automated sniff tests to aid the publisher as well as pre-populating data required of the author.

These are just ‘top of mind’ issues that needs to addressed. As I have said in many forums, HTML as the source file for manuscripts is the way scholarly publishing has to go…its not about google-docs as such, it is about standards based structured HTML as the source file format for manuscripts.

English isn’t my mother tongue language and I am far from any good user of it . I always sent manuscripts to journal , but they send it back to me because of used English . I am suffering of that with no near solution to this problem.