When new publishing ventures are launched, there is a journalistic tendency to depict them as “disruptive,” “innovative,” or “game changers.” In reality, very few new ventures are. Two years in, most new ventures can hope to be alive, let alone prove to be disruptive. Most of these companies just fade from our memories. There is very little incentive to go back and revisit them.

In 2012, I published two posts on PeerJ. The first, arguing that this new publication represented a clear cultural shift, from the staid publishing houses of Europe and the Eastern United States, to a West Coast Silicon Valley startup mentality. The second post took a more critical look at their publication business model and and argued that this venture capital-backed company had an exit strategy built right in and we could predict when they would sell by the shape of their author membership curve.

Rather than taking the easy route of more idle speculation, I decided to take a data-driven approach and look at what PeerJ was publishing and whether it leads to any insight on the success (or failure) of this new venture.

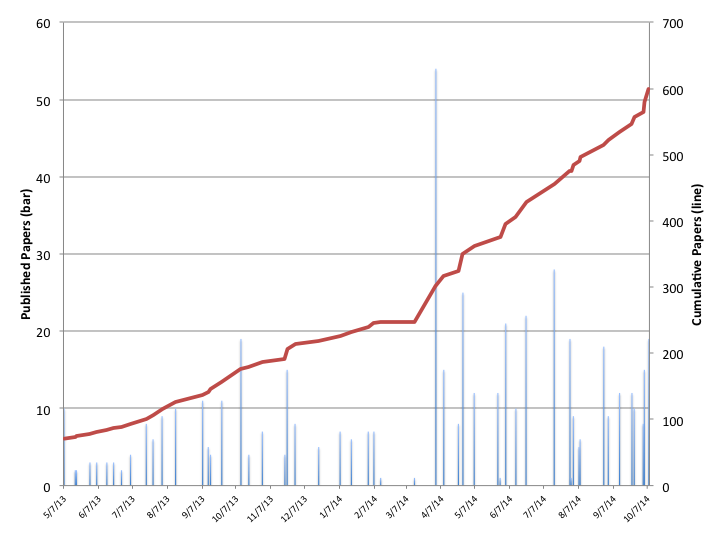

Based on publication data that I parsed from PubMed, between May 3, 2013 and October 8, 2014, PeerJ published 600 articles and one correction. PubMed does not index PeerJ PrePrints. Their publication rate has been pretty steady (Figure 1 below), and appears to be rising somewhat in 2014.

PubMed lists the online publication date for each article, but strangely provides just the PubMed batch load date in their data extract. The periodic spikes in new papers and authors in the figures below reveal those weekly PubMed loads.

From the PubMed metadata, I was able to count the number of authors per paper, and with a little work, calculate whether the author was new or returning. Remember that PeerJ works on a lifetime membership model where you “pay once, publish for life.” Returning authors, therefore, do not bring additional revenue to the company although they do incur expenses.

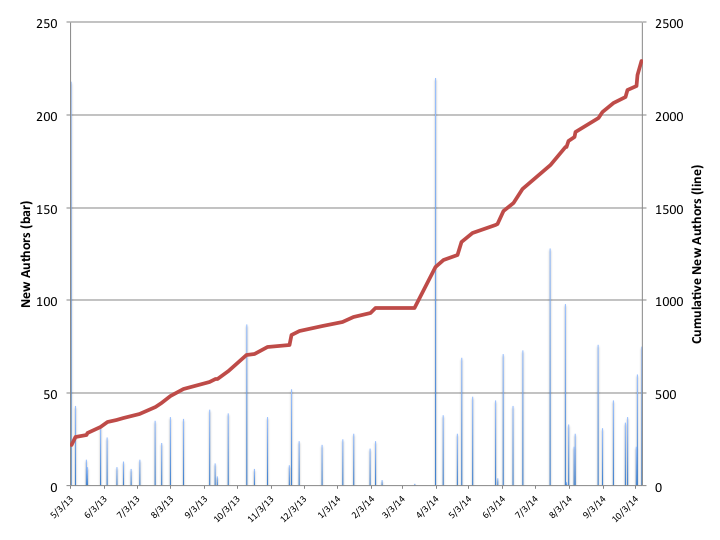

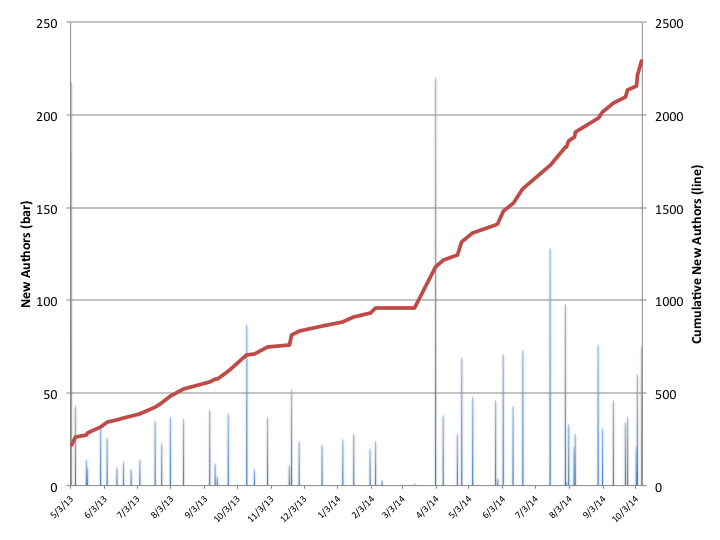

Figure 2 plots the number of new authors (blue bar) by date, as well as the cumulative number of new authors (red line). Like Figure 1, the number of new PeerJ authors is rising steadily and may be increasing in 2014.

The 600 published PeerJ papers included 2557 authors, 2290 (about 90%) of whom were unique. The median number of authors per paper was 4, with one paper listing 18 authors. The vast majority of unique authors (92%) were listed on just one PeerJ paper. The remaining 8% (193) were repeat authors: 143 (6.2%) authors were listed on two papers, 34 (1.5%) were listed on three papers, 10 (0.4%) authors were listed on four papers, 4 (0.2%) authors were listed on five papers, and 2 (0.1%) authors were listed on six PeerJ papers.

While these two graphs look almost identical, they convey two very different things toward measuring the success of PeerJ. The first graph shows that the company is able to attract and publish new papers. Yet, compared to multidisciplinary open access journals with similar scope (viz. PLOS ONE), PeerJ is still very small. Submissions to PeerJ PrePrints may have been eclipsed by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory’s bioRxiv and it appears that PeerJ may be fighting to attract new preprint authors by dropping all publication fees if their authors use their preprint service.

Even thought the number of publications is increasing, we can’t simply convert them into reliable estimate of a revenue stream. Like most open access startup journals, PeerJ has had several periods where author fees were waived, so not all authors and not all papers paid for memberships. As a private company, the financial details of PeerJ are locked tightly in a black box; however, news of a new round of funding by venture capitalist, Tim O’Reilly and SAGE Publishing may give hints on the financial self-sustainability of PeerJ.

Since last writing about PeerJ, the company has introduced two new pricing models. First, it is now easier for a single author to pay for co-authors or for the entire author group. This makes PeerJ operate like most other open access (and hybrid) journals in which a single author is responsible for all financial details. Second, PeerJ introduced an institutional “pre-pay” model in which libraries can purchase memberships for their institutional authors. If I remember correctly, this institution-pays model was first introduced by BioMed Central nearly ten years ago. These two price model introductions may indicate that the individual membership model is not working, or at least not as well as PeerJ‘s founders predicted.

To me, the more important graph to watch is the number of new authors (Figure 2). The commercial success of this company is predicated on an increasing stream of new authors willing to pay lifetime membership fees. This is not a bad assumption to make for a young journal in which the vast majority of members are first-time authors. It does start to break down if the number of new (paying) authors is unable to support the growing expenses of returning authors.

Within a few weeks, PeerJ content will be indexed in the Web of Science and BIOSIS Previews, according to Joelle Masciulli, Editorial Director of the Web of Science at Thomson Reuters. At this point, PeerJ has not been assigned an Impact Factor. As most scientists consider journal prestige and Impact Factor important in their submission decisions, receiving an Impact Factor next year could lead to a rapid influx of new PeerJ submissions, as we saw with PLOS ONE. Alternatively, a low Impact Factor could lead to a steep drop-off.

In sum, PeerJ introduced a new publication model that was “innovative” in the true sense of the word; however, changes in its pricing models are making this journal look much more like other open access and hybrid journals. Competition from bioRxiv may have eclipsed PeerJ‘s prospects of a business built on preprints. PeerJ is growing, publishing more papers and attracting more authors, although it is not clear whether the company is moving toward financial sustainability. In a crowded market of multidisciplinary open access journals, the success/failure of PeerJ may be determined when it receives its first Impact Factor.

Discussion

30 Thoughts on "PeerJ Grows Steadily With Papers, Authors"

I wonder how big a motivator the potential cost savings offered by PeerJ are in a well-funded field like the life sciences. If you’re spending grant money, or increasingly, spending from a university or other fund created to pay OA author fees, how sensitive are authors to saving a few hundred or thousand dollars? If you’re spending someone else’s money, why not go for the best journal you can get your paper into, the one that will offer the most career reward, rather than the one that offers the best price?

There may be some market segmentation going on with regards to access to funding. While those with ample grants may not be sensitive to the costs of publishing, those without grants may be highly sensitive, and PeerJ is trying to appeal to the latter. When PeerJ is fully indexed by the Web of Science, one could do an analysis of paper funding sources and compare them with PLOS ONE or other similar journals to see if there is indeed a difference. Similarly, one could compare the number of authors per paper as PeerJ’s pricing model places downward pressures on guest authorship (e.g. deans and department heads). This would also indicate price sensitivity.

I surveyed authors from PeerJ and a number of other mega journals (see: https://peerj.com/articles/365.pdf )

About 35% of PeerJ authors said they used grant funding for the fee and almost an equal number said they paid the membership fees out of pocket.

I think authors are being drawn to PeerJ for a lot of reasons. Cost I am sure is an issue for many but PeerJ also provides excellent service including very quick review times. That matters to authors at least is does to me. They are also providing a lot of nice tools for readers. If the citation rates are respectable as I expect it will be then I think and hope the journal will really take off.

Note that in the survey linked in the article above, Quality of Peer Review and Speed of Publication ranked numbers 3 and 5 as far as importance in how authors choose a journal.

David, this survey is very helpful to the discussion! In Table 6, the percentage of authors using personal funds to pay for publication was much higher for PeerJ and SAGE OPEN (the two least expensive journals) than they were for PLOS ONE or BMJ OPEN (32.3% and 62.6% versus 7.8% and 10.8% respectively). This may indicate that there is market segmentation based on personal vs. institutional funding. I should note that 26.7% of PeerJ respondents reported receiving a “Promotional fee waiver” so we don’t know whether they would use grants or personal funds if the waivers were not available.

Thanks Phil. I agree!

What’s really interesting here is that if this is a viable business model, it could solve some of the problems seen for OA in less well-funded fields like the Humanities. Though it’s unclear if the level of peer review and editing provided by a system like this would suffice for publications in those fields, which usually feature longer articles subject to a great deal of revision.

I agree. Another difficulty however is that papers in both the social sciences and humanities tend to have fewer authors making it even more difficult for this business model to be viable.

That said, I think it is possible to have lower cost options for professional quality publishing in those fields. Ubiquity Press is a good example partnering with societies and university providing basic professional publishing services at a base APC of I believe $400. I believe that even includes a managing editor to work with the society/university in managing peer review.

It is not $99 for being able to publish one article a year for life but it is getting down a point that is more affordable for people in the humanities and social sciences.

“As a private company, the financial details of PeerJ are locked tightly in a black box; however, news of a new round of funding by venture capitalist, Tim O’Reilly and SAGE Publishing may give hints on the financial self-sustainability of PeerJ.”

It is not unusual for a start-up to have several funding rounds. The initial funding (or “seed”) round, is typically focused on raising enough funds to build the product and take it to market. Seed funding seldom takes a new venture to profitability. This is by design — investors want to make sure the technology works, the team is able to execute, and the market is responsive before providing more funding. It is not uncommon to have several additional funding rounds (which are usually designated by letters: series A, B and C rounds). As you note above, PeerJ recently closed its series A round with funding from SAGE and O’Reilly. That O’Reilly was part of both the Seed and A round is a positive sign and signals the PeerJ’s execution is in line with investor expectations.

I would not read too much into the recent series A round. This just means PeerJ spent its initial round of funding on their initial build and on getting to market.

What this shows is that PeerJ only reaches profitability on a considerable scale. According to your analysis, the journal published papers from 1,250 unique authors, of which approximately 25% had fee waivers (as we learned from the link provided by David S. above). So that is 937 paying authors. Let’s assume they all paid $150 (though in reality some likely paid $99). That is $140K in revenues. According to their website they have 8 staff, including founders. Most of them are engineers or senior staff so let’s call it an average salary there of $125K x 8 = $1 million. Some of the staff may be part-time but this is just a ballpark. Plus overhead = $1.3M. That is just people. Then you have technology costs, marketing costs (travel and speaking etc.), and article processing costs (which obviously go up with volume).

So they are currently spending somewhere in the neighborhood of $1.75M annually while pulling in $140K. This means that PeerJ will need to realize more than 10x growth to get to break-even. Because their article processing costs go up as their volume goes up, they will actually need somewhere in the neighborhood of 20x growth at their current price point to get to break even — that would mean 6,000 papers per year. That is just to hit break-even. And at that point they will likely have to re-invest in technology (many organizations find that technology that can support 600 papers annually doesn’t always support 6,000 papers) and hire more staff.

So given increased costs, to eek out even a modest margin they would have to grow even further. Of course this is in the realm of possibility and clearly journals like PLOS One and Optics Express have reached this volume.

This is obviously all back of the envelop math and I’m sure is off to some degree (but not by an order of magnitude). The key point is that PeerJ only works at considerable scale (8K – 10K papers annually) at their current price point. The question is whether securing an impact factor will trigger the kind of step-factor growth they will need to put them on this trajectory? (Of course profitability is not necessarily important to start-up economics but it will likely be to an acquiring organization).

Michael, where does the 1250 authors figure come from? Phil has listed above 2290 unique authors. If 25% were waived, that would mean 1,718 paying authors since May 2013.

As a regular Joe-the-Plumber of the biological science community, when I read some of these comments, I am left with this distinct uncomfortable feeling in my gut: on one hand, we have one set – a minority – of marketing-related individuals and VCs, determining the fate of the direction of science publishing. In their mind there are only limited words in their lexicon, such as profitability and/or satisfying stock-holders. Then, on the complete opposite pole are the scientists, who simply want to prove their hypothesis and get it published as a paper, preferably in a “respectable” journal. There is increasingly, I feel, a serious disconnect between these two groups, with the latter thinking that occasional spot surveys with the chance of winning a measly Amazon gift card, can somehow capture the essence of the needs of the latter group. I have often claimed that the IF is one corrupting factor in science while the other is money. If you ask a scientist if they would publish in PeerJ or any other OA journal that asks anything more than 100 US$ to publish one PDF file if they had to pay from their own pocket (and I don’t mean from their own lab funds, I really mean from their own hard-worked salary), I think you might find an overwhelmingly universal no. In other words, it is precisely because global academia, especially from developed countries, is built up so incorrectly, providing funding willy-nilly to pay for these ridiculous OA fees, that we are seeing anger, frustration and chaos building up. It is precisely because academic institutions have been brain-washed (by the publishers?) into thinking that if they don’t offer their scientists often vast reserves of money to pay for OA fees then their reputations will suffer a serious knock, that we are seeing this constant gaming and reassessing of the risks to profitability by OA journals like PeerJ which are, to me, nothing more than experimental ventures rather than true academic bodies. It is only the elite managers and marketing fellas at the top of the food chain that are always seeing things in a rosy light. This is nothing less than a classical class war of modern times. And at some point, there will be revolt, as is already being experienced with disgusted entities around the world who see through this farce and abuse of the scientific community, and who are trying to find alternative options to publish, albeit unsuccessfully in many cases, the so-called “predatory” OA publishers. So, while I appreciate the discussion taking place about the profitability of PeerJ as it games and gambles with its first IF score, it leaves me with a sickening feeling in my gut, to be honest. I for one, do not support PeerJ (or any other OA outfit that demands money to publish ONE PDF file) because I refuse to pay for having my intellect published which would amount, in essence, to a double taxation.

No mention was made of the publishing plan between PeerJ and Max Planck Society. With a budget in the billions annually, surely this is important.

http://blog.peerj.com/post/97050873493/max-planck-authors-can-now-publish-for-free-in-peerj

Our library (agriculture and veterinary medicine) established a publishing plan with PeerJ. We followed the example of Oregon State, another land-grant (https://peerj.com/institutions/case-studies/19/oregon-state-university/)

This Open Access week is a very happy one for us. Instead of sponsoring talks about what could be in open access in agriculture and veterinary medicine, PeerJ offers our authors innovations, including open peer review and links to popular press coverage of the work, and makes it easy and affordable for us and our authors, saving valuable time all round.

Read the bloghttp://blog.peerj.com/.

Last year, our open access week focus was retaining rights to your own work (http://libguides.utk.edu/retainyourrights). Difficult and scary for authors and difficult to explain for librarians.

This year, PeerJ has made OA Week easy and happy indeed. Copyright is retained by the authors, of course! Many thanks PeerJ!

Ann Viera

Pendergrass Library

Hi. I did indeed mention PeerJ’s institutional pricing model in which libraries can purchase memberships for their authors. See 4th last paragraph on pricing models. I’m happy that PeerJ made you so joyful this OA Week.

It is my understand (based on the language on the PeerJ website) that the institutional publishing plans entered into by Max Planck and others are pre-paid plans, meaning the institution is simply paying on behalf of its researchers (please correct me if that is a false assumption). If so, this really doesn’t change any of the economics discussed above. Who pays, assuming they are paying $100 – $150/author, doesn’t really matter.

I would not argue with the assertion that PeerJ provides a great service to authors at a very affordable price. The question is at what point (what volume of papers/authors) it becomes a viable ongoing concern? At present, every paper published by PeerJ is largely subsidized by venture capital investment. That is obviously not a sustainable long-term arrangement.

It is an interesting model. I do not think that the number of new authors is likely to drop, because a major function of research training is to supply the needs of industry, commerce and government. With 1% of PhD students (in the UK at least) remaining in academia, 99% pursue science careers in these other sectors. So the PI will maintain “free publishing”, but with each cohort of students and postdocs will be bringing in new authors.

The model is interesting and one that, for example, the Royal Society of Chemistry is moving towards – institutions with a library subscription get a number of OA vouchers.

The other issues are that not all research funding pays for OA (though it does increasingly) and most labs are careful with their resources and do not see the point of spending 1000s more to publish in journal X, when it is the paper that determines how the work is received by the community and so citations, not the journal name.

Even if the number of new authors grows there is a problem. These are lifetime memberships so new authors become repeat authors who pay nothing to have their papers published. It is often said here that it costs a lot to publish a paper. As the ratio of repeat to new authors grows the revenue per paper published drops. I do not see how this can ever become sustainable, including by scaling up. More new authors translates into more repeat authors.

Most graduate students and postdocs do not pursue academic careers and publish only a few papers. Thus even when the growth in the total number of authors and published papers stops, a large fraction of the authors will be new graduate students who publish their first paper and are thus first time authors. Also, PeerJ might change its pricing scheme for future authors.

in fact Lotka’s law says about 80% of authors publish only 1 or 2 papers. Perhaps PeerJ is betting on Lotka’s law, but I do not see how they can publish even one paper for $99 to $150, or less given all their free memberships. Raising prices later is also a well known strategy. For example a new country club may even give away memberships to get a critical mass of members, as PeerJ is doing to some degree. This is the most likely strategy; the only one that works in my estimation.

David I believe they are basing the model in part on Lotka’s law. In addition, the small percentage of authors that publish a lot of manuscripts generally spread them around..

I believe PeerJ is temporarily waiving the membership requirement to publish NOT giving away free memberships that allow someone to publish in the future. It certainly isn’t an unusual strategy for new companies.

There are on average about 5 authors on each article in the life sciences which in theory would give PeerJ roughly $495 to work with for the first article. Given Lotka’s law and the fact most highly productive authors do not always publish in the same journal the model might work if they are very very efficient and are able to crank up the volume of articles published to something like what PLOS ONE has. PeerJ is already in the WoS and will have an impact factor next year. If it is in the ball park of what PLOS ONE’s is that seems quite likely to me I think they will grow very fast. A one-time $99 fee or $1,350 every time you publish. Which would you choose for essentially the same service?

I think the membership allows one paper per year so prolific authors can do that and still spread their papers around. There is also the fact that if what is said here frequently is true then they cannot publish even one paper for $99, much less several. As I have said from the beginning, it just does not work.

There are three levels of membership, $99 for one article a year, $199 for two and $299 for unlimited. Each author on the paper must be a member. This means each paper generates on average about $495 the first time the authors publish since there is on average 5 authors. That also assumes they have the lowest level membership.

Good point, so the front end numbers get considerably bigger, perhaps even bearable. The real danger is then the repeat authors.

I agree. That and being extremely efficient in how the journal is operated which will require a large volume of submissions.

Agreed, though most new authors (graduate students, postdocs) are only authors for 3-9 years. In addition, people tend to spread their papers around journals, which will reduce the effect of the shorter term authors returning – I am very curious as to the calculation here, as it must have been done, but for now we can only guess!

Thank you for compiling the data and writing this post. The post and the comments covered the important aspects, and I would have liked to see a bit more discussion on how PeerJ attracts higher quality articles and more audience among influential mainstream scientists. Some may think that this falls under the rubric of the IF, but I do not. For me this is a question of whether (i) a PeerJ paper gets high visibility (currently bioRxiv preprints seem to get higher visibility/downloads that PeerJ papers) and (ii) PeerJ publishes papers that are high quality and of interest to the mainstream researchers. The IF will be only an imperfect and delayed reflection of these two factors. Thus, I think that the success or failure of PeerJ (even in financial terms) depends on these two factors.

I think that the PeerJ model has the potential to solve many problems in science publishing, and I want to see it succeed. I hope PeerJ finds a way to stimulate the growth in the quality and the visibility of its articles, not just their number; the increase in the number of published articles will follow naturally.

Stacy Konkiel’s (of ImpactStory) slideset developed for Open Access Week 2014 expands the discussion of how research is changing and how scholars can communicate directly (“the rise of collaborative, web-native research). “Why Open Research is Critical to Your Career” developed for Open Access Week https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1gv_KRzvp6DDl9gjwTReDhvPrnv66ttOL6qVZwovygmM/pub?start=false&loop=false&delayms=3000#slide=id.p.

Communicating directly is also discussed by the Eisen brothers in this interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=if0L3JDWNAA

I’ve found as a veterinary librarian the audience for veterinary research is so much broader than authors imagine that new publishing models are sorely needed. Affordability is crucial because vet med is such a small community of practice with a huge mandate: protect the health of all species but one. So many species to study by fewer researchers and far less funding.