During the whirlwind annual meeting of the Society of Scholarly Publishers in San Diego this summer, I had a chance to chat with the brains behind textBOX, a new company offering a suite of accessible publishing services. Inspired to enrich the world’s online images with descriptive information, accessible to readers and computers alike, textBOX offers what may be a game-changer for scholarly and educational publishers in optimizing content discovery and access.

The textBOX strategy is focused on a major sticking point in reaching accessibility compliance: descriptive “alt-text” for images and graphics within scholarly publications and educational platforms. While captions are sometimes available, they often do not provide the full range of information embedded in photos, tables, videos, or other media files — more often than not, search engines and text-to-speech applications skip any graphics missing background information that describes the image in plain text.

Bringing a depth of expertise garnered by a collective 20 years driving accessibility enhancements at SAGE Publishing, Caroline Desrosiers and Huw Alexander explain their motivations behind launching textBOX and what they predict for the future of machine-readable images in scholarly and professional publishing. In full disclosure, I had the pleasure of working with Huw and Caroline during my tenure at SAGE, and have always appreciated our shared passions for leveraging technology to humanize and advance scholarly communications.

Why is descriptive text for images so hard? What prevents publishers from enriching their flat image files with human- and machine-readable descriptive text?

Technical improvements have enhanced many aspects of the digital publishing workflow, such as the introduction of EPUB3 content and ONIX eBook metadata distribution. However, there are still many technical challenges to address, especially around accessibility. Humans, for all our idiosyncrasies, are still an essential part of the process. Authors and editors are still required. Image describers are still required.

Artificial intelligence has developed significantly in recent years, but it is left defeated in the face of complex images — an integral part of publishing. The human aspect of image description is one of the most difficult to address for publishers as it is a developing field and expertise is not widespread. For publishers producing born-digital or digital-only products, visuals may be fluid and require ongoing image description work. There is also the question of resources and time. Are authors empowered to create image descriptions for their work? Do overworked editorial staff have the time or skills required to create the descriptions? For publishers, addressing each of these questions is a challenge, but also an opportunity.

How does accessibility improve usability for non-disabled users?

The impact of accessible design has been felt in two ways: technological crossover and enhanced understanding.

Accessibility is specialized and pushes the limits of productivity and communication. Technology companies, such as Apple and Microsoft, understand the value of adopting universal design techniques to improve the productivity and functionality of their services. Services initially aimed at improving product accessibility soon shift to the mainstream as non-disabled users discover the benefits. For example, innovations like captions help people read in noisy or quiet environments. Smart speaker products such as Amazon Echo, Google Home, and Microsoft Dictate serve many purposes and enable users to be more independent and hands-free.

The second aspect is enhanced understanding. We live in a visual world and are surrounded by content at every step – from our phone screens to digital billboards. We filter this content, to an extent, but the volume of visuals demanding our attention is overwhelming. As a result, we often miss the details. Sherlock Holmes famously said to Dr Watson in The Scandal in Bohemia, “You see, but you do not observe. The distinction is clear.” If you’ve ever taken an art gallery audio tour you realize the benefits of image description and walk away with a newfound understanding of the artwork. Image descriptions provide all users with an expert perspective, context and meaning that facilitate engagement and learning for the user. They open up the visual world to the visually impaired and dyslexic readers but also provide additional guidance for non-disabled users who need help with complex images.

So, the benefits of image alt-text extend well beyond accessibility for those readers with sensory limitations, yes? What other values are you seeing, perhaps they improve search and discovery for other readers?

Image description is a powerful marketing and discoverability tool that is too often overlooked. In a recent survey, WebAIM assessed 1 million website home pages and found that 57% contained either missing or poor quality alt-text image descriptions. Publishers select visual content for a reason — to tell the story of their company and their products. By not including image descriptions, they are preventing many users from accessing visual content.

Alt-text recognition is firmly embedded within the Google search algorithm and has enormous untapped potential for the publishing industry. The inclusion of image descriptions creates a marketing layer that drives traffic to the publisher’s content and provides a more granular level of data than existing standard metadata feeds.

Image description also improves the search capabilities within digital products. Customers expect digital products to function like websites in terms of efficient search functionality. Quality image descriptions are integral for highly visual platforms and content because they help readers quickly and seamlessly navigate to an image, table or figure.

Another positive aspect of image description is the opportunity to broaden the range of audiobook content. Audiobooks are the fastest growing format in book publishing. Image descriptions improve the user experience for those who prefer to listen, thus creating a wider potential audience for publishers.

What is different about textBOX’s approach to image description?

textBOX is unique in that we focus exclusively on writing image descriptions. We both come from a publishing background and understand the issues that publishers face, as we have encountered them ourselves. At textBOX we spend every day developing the art and science of image description. Image description, especially for complex images in academic publishing content, can seem like a daunting task. To address this challenge, we created a new image description methodology, focus|LOCUS, to simplify the process and deliver consistent, high-quality descriptions that improve the usability and discoverability of digital products.

How do you approach writing alt text for different types of images, such as photos, diagrams and symbols?

focus|LOCUS is the foundation and framework for all textBOX image descriptions. We begin by breaking down the image into different parts or elements. Describers identify the focus element, or starting point, as well as the relevant locus elements that surround the focus. Describers then create a logical pathway through these elements to build the image description. The elements change for different types of images but the focus|LOCUS approach does not.

Let’s take two very different examples from a book: a graph and a photograph. Both contain a message and were included for a reason. In each case, we tell the story of the image by weaving together the relevant details (the data points and trends within the graph and the artistic style and placement of the photograph), creating an immersive description for the user. Every image tells a story and the focus|LOCUS approach provides a framework to tell that story.

How does the context surrounding the image change the writer’s approach to description?

The relationship between the text and image is critical to writing quality descriptions. Every image must be analyzed against the backdrop of the surrounding text to assess whether a description is required. Context is the key to conveying the author’s message.

The describer must decide what information is relevant to the reader. It is not necessary to repeat information that has already been provided by the surrounding text. If the image does not include a caption or surrounding text (e.g., images on websites, advertisements), the describer must decide what information the content provider means to convey through the image.

What makes a good image description?

As we’re guests in the Scholarly Kitchen, let’s use a cooking analogy. A chef may spend hours creating an elaborate meal and carefully laying it out before her guests. She will know if her efforts have been worthwhile only when her guests taste the dish. Essentially, she is focused on the end result and the experience of her users. It is the same for image descriptions. It is all about delivering a product focused on the user experience.

We approach visual content from the perspective of the print disabled user. How can we tell the story of that image? How can we convey the relevant information from the image in an engaging and efficient way? The true test of a good image description is being able to recreate the image using only the description. We need to both see and observe so that we can help our users accurately visualize the images.

What’s the scope, how many students require accessible image descriptions these days?

The National Center for Education Statistics (2016) reported that 11.1% of undergraduate students have a disability. In 2017, The NCES Condition of Education 2017 report estimated 8% of postgraduate students have a disability.

Between 2000 and 2015, total undergraduate enrollment in degree-granting post-secondary institutions increased by 30% (from 13.2 million to 17.0 million). By 2026, total undergraduate enrollment is projected to increase to 19.3 million students (+14%).

Total enrollment in post-baccalaureate degree programs was 2.9 million students in fall 2015. Between 2015 and 2026, post-baccalaureate enrollment is projected to increase by 12% (from 2.9 million to 3.3 million students).

What does the future of image description look like?

Forward thinking publishers are embedding accessibility into their practices and publishing born-accessible eBooks. These publishers will have a competitive advantage and benefit from improved traffic to their digital products. Also, improving the “interstitial reading” experience – the reading we do in those in-between moments, during our morning commute or walking the dog. This is one of the reasons why audiobooks and podcasts have become so popular. Publishers need to think about how user behavior is changing and adapt their products to meet their customers’ preferences. Accessible image description improves usability, discoverability and creates new business opportunities for publishers.

Publishing has always been about telling immersive stories that capture the hearts and minds of readers. Image description is an opportunity to tell these stories and the story of the publisher to a wider audience. The shift to the visual in publishing means that the future of image description is a vivid one. We look forward to describing it.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "Thinking about the Art and Science of Image Description: An Interview with textBOX Founders"

Any chance that textBOX could provide an example with the image used in this post? I’d be keen to hear how it would be described. In the comments field would be okay!

Thanks!

Thanks very much for your question, Heather.

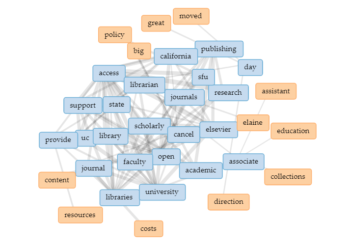

Out of interest we checked on the automated alt-text generated for this image by a fairly well-known software company:

“A close up of food.”

Not quite accurate. Unless you’re Hannibal Lecter.

Here’s our version:

A computer-generated image of a top-down view of the brain illustrates the distinct logical and creative sides of the brain.

The left hemisphere of the brain is overlaid by 3 separate node networks. Each circular node differs in size and pale colors, and each are linked by connecting edges. The node networks represent the logical side of the brain that controls analytical thought, reasoning and mathematical skills.

The right hemisphere of the brain is fringed by paint splashes of vivid color from blue to red to violet to yellow. The paint splashes represent the creative side of the brain that controls imagination, intuition and artistic thinking.

Our descriptions aim to provide a structure for the reader so that they can visualize what is being described. We then tell the story of the image by following a logical pathway through the elements and details within it. We also use evocative language to create a more immersive experience for the reader. The ultimate aim being: can the original image be recreated from the description? We hope so.

Hope this helps. And thanks for the question!

The link to textBOX’s website doesn’t appear to be working. It appears to link to https://www.textboxdigital.com/https:/textbox.io/ instead of just https://www.textboxdigital.com/

I have long been taught that alt text should be short. What is described in this blog post (and what is shown in the example alt text in the comment above) is far from short. Are you saying that the length of alt text does not matter as long as it describes the image accurately/completely?

Hey Kevin,

Yes, good point. The alt-text should be a short description but it under certain circumstances, depending on the context, more complex images need to be described using a long description.

The alt-text for the image above could be something like:

“A computer-generated graphic illustrates the creative right brain and the logical left brain.”

If the context within the book or website requires a more in-depth description then a long description would be appropriate. We recommend alt-text be restricted to around 16 words. There are no restrictions on a long description.

Hope this helps,

Huw