Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Roy Kaufman. Roy is Managing Director of both Business Development and Government Relations for Copyright Clearance Center.

One obvious impact of the recent OSTP memo calling for zero embargo public access policies for articles resulting from research funded by US Federal agencies is that it will increase the speed at which publishers commit to an Open Access (OA) future. While the US policy differs from Plan S in that it purports to be “agnostic” toward business models, the end result, the flipping of hybrid/subscription journals to fully-OA, may be the same.

Whether driven by funders, governments, publishers, institutions, a genuine belief in an open future, or some other motivating factor, the so-called “Global Flip,” will require major changes to the fundamental economics of journal publishing for it to be sustainable. In order to succeed in a flip, a holistic approach is needed, especially to ensure the survival of high-quality society-published journals on which both corporate and academic researchers rely. Unfortunately, much of what has been written about OA from the funder perspective looks at the journal market as comprised exclusively of two binary revenue inputs: APCs and institutional (academic) subscriptions. The thinking is that if we can somehow manage to flip the institutional subscription revenues to OA models, the market will sustain itself.

By way of example, cOAlition S supports publishers’ efforts to flip journals, defining a Transformative Journal as “a subscription/hybrid journal that is committed to transitioning to a fully OA journal.” In addition, it must:

- gradually increase the share of OA content and

- offset subscription income from payments for publishing services (to avoid double payments). (emphasis added)

cOAlition S also mandates that articles apply a CC BY license to be considered fully Open Access in keeping with the Berlin and related declarations.

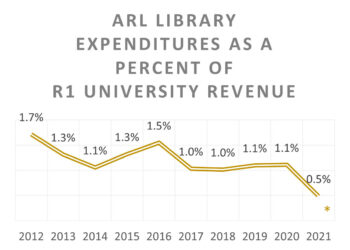

In a similar vein, the vague economic analysis in the OSTP memo contains the following statement: “Libraries pay for journal subscriptions. Taxpayers indirectly fund libraries to pay for access to journal content through journal subscriptions. These funds are included as ‘indirect costs’ charged against federal awards.” This is certainly partially true, but it is an incomplete view (and not only because at many institutions, large portions of the acquisitions budgets come from sources such as tuition and student fees).

But Wait There’s More…

From the institutional perspective, this binary view makes sense. Institutions historically paid for access to read subscription journals and are now being asked to pay to publish the content in an open manner. However, even in a perfect economic system where budgets could shift, there are sources of revenues outside of this closed system which, unless considered, may in fact impede the global flip. This is especially true with society-owned medical journals.

Overlooking these potentially significant revenue sources makes a flip less likely as the economics simply will not work. Indeed, this is one reason many publishers and societies have continued to use a CC BY- NC license (or make those licenses available on an optional basis to authors), to the frustration of many OA advocates and funders.

As one strongly pro-OA executive at a large publishing company told me, “When looking at what we will flip and when, we take a holistic look at all sources of revenues.” There are too many revenue sources to consider in one article, such as member subscriptions, advertising, photocopying, and individual article sales. I will focus on three revenue sources missing from the flip discussions and which are especially relevant to biomedical — emphasis on “medical” — publishing: corporate subscriptions, reprints, and permissions. I focus on biomedical because this field has both the highest uptake of OA, and because it benefits greatly from the revenue sources missing from the global OA conversation.

Corporate Subscriptions

Corporations subscribe to journals to support their research goals. A typical breakdown for full-rate journal subscriptions to a society-owned medical journal is 70% academic, 15% government/hospital, and 15% corporate, according to Andrew Pitts of PSI, a data analytics company serving the journals publishing industry. By contrast, fewer than 3% of OA articles are typically authored by researchers working at corporations. In other words, corporations pay a far lower percentage of the costs under an OA model than under a subscription one. As more content is made available for free in a flip, corporate subscriptions will decline. This is generally viewed by advocates as a benefit of OA, but it creates a sustainability challenge. Corporations do not subscribe because they want to pay money; they subscribe because they rely on the content.

Reprints

Commercial reprints are a significant source of revenues and profits in biomedicine. Commercial reprints are purchased by corporations for marketing and product awareness and thus the library/funder community has little exposure to them. The volume and value of reprints purchases vary by discipline and journal, with most value concentrated in biomedical fields, especially clinical medicine. For some journals, reprint revenues exceed subscription revenues. According to a VP of medical publishing at a large publisher, “…for many big society biomedical journals, 30-35% of the revenues come from corporate sales, with reprints being the lion’s share. If you include corporate subscriptions and other rights licenses, a 50/50 revenue split between academic institutions and corporations is not unusual.” As with subscriptions, the ability to make commercial reprints without copyright payments is a feature of CC BY open access. Today, corporations are willing to pay a premium price for reprints to higher impact (often society) titles because these are more valuable for their purposes. As long as the policies do not lead to closure of titles they need, or the shunting of relevant articles into lower impact journals for compliance reasons, corporations win. If those things happen, they may save money but lose benefits.

Translation Rights

Rights and permissions typically account for about 5-10% of revenues for biomedical journals, excluding reprints. In some cases, such as academic photocopying, the revenues are modest and unlikely to impede a flip. In other cases, revenue, plus brand protection and quality control block flipping. Earlier in my career I worked on translation versions of journals, which were typically sponsored by a pharmaceutical corporation, carried the branding of both a journal and a society, and were distributed by controlled circulation to doctors outside the US. As an attorney, I did not focus on the revenues, although they were significant. My focus was ensuring that the translation’s sponsor was a legitimate entity and that the journal’s editor could maintain quality control through appointing the editorial board and other reasonable means. This was how publishers prevented conflicts of interest, e.g., derivative publications of oncology journals being packaged by tobacco interests. Said one executive recently, “I have a journal which earns roughly $250,000 per year from recurring translated digests. Leaving aside loss of revenues, my societies would question my judgement if editorial control were not clearly ensured. This is one of the reasons medical societies are slower to embrace full CC BY open access.”

Refining “Open”

These considerations are not new. As far back as 2012, David Crotty raised some of these issues — especially with respect to reprints — in “The Financial Burdens of the CC-BY License for Scholarly Literature”. Ten years later, the industry is more committed to an open future. Everyone I interviewed in preparing this article conceptually supports “open” and works for an organization that has committed to an open access future. All expressed concern for the real-world implications of a flip on the long-term viability of some journals and so are deeply skeptical of a full transition.

As noted in David’s 2012 post, using licenses such as CC BY-NC and CC BY-ND would at least protect some of the revenues and alleviate some of the concerns. However, CC BY is increasingly the coin of the realm for OA, mandated by funders and embraced as a competitive advantage by publishers for whom corporate revenues have never been significant — and increasingly by some who have. And while the OSTP Memo does not specify a license type, I suspect strongly that OSTP is now, or will soon be, working with agencies to craft policies that will require open licenses. That some open licensing will be required can be inferred by the requirement to deposit a machine-readable copy. So-called “machine reading” requires copying and processing, and as such generally requires a license. Without rights, a machine-readable copy is at best the digital equivalent of a rock, and at worst an invitation to a lawsuit.

The journals that are best positioned to flip are the ones where academic institutional revenues account for the majority of total revenues. Those journals are more likely to be publisher-owned or “proprietary” journals, and ironically, the big journal publishers will likely do just fine under these new OSTP policies. Society journals, on the other hand, are more restricted. As the medical publishing VP quoted above stated, “While my colleagues [responsible for OA] ask me to flip these titles, we cannot. The loss of corporate revenues would threaten the ongoing sustainability of the journal. In the last few years, societies have lost meeting income and membership is flat. Why would they want to transition to full OA?”

I don’t doubt for a minute that there is theoretically enough money in the system overall to support a global flip, and such a flip would create many advantages for stakeholders. However, a sustainable flip is unlikely to succeed without replacing all lost income (including those discussed above), and new models must reflect that. If it turns out that articles published from US-funded research are not ultimately limited to open licenses, then at least some of these revenues can be retained from that pool of content, but some will certainly be lost.

I know that some will say “So what? Publishers just need to accept lower margins.” In many cases, without properly accounting for missing revenue sources, there will be no margins remaining. Societies, and by extension, society itself, will lose.

Discussion

5 Thoughts on "Guest Post — Missing Revenue in the Global Flip: Getting the Open Access Math Right"

I suspect few (no?) publishers want to reveal the details of these revenue streams but I wonder if CCC or another group might be able to be an intermediary providing examples of evidence-based common revenue profiles without publisher identifying details. How much revenue are we talking about in the more common profiles of revenue make-up? I’m not convinced it *all* has to be replaced but, leaving that aside, understanding the parameters of these revenue profiles would be useful I think.

As many of my society publisher clients hyperventilate over a zero-embargo policy, I tell them to breathe and wait for the details to come out. Many would be able to survive policies that allowed authors to self-archive manuscripts in their institutional (library) repositories. A machine-readable deposit of all accepted, peer-reviewed manuscripts into PubMed Central may create some existential problems as it would seriously reduce the perceived value of journals to library subscribers. Prior research shows that a significant share of readership leaves journal websites when content becomes public in PMC 12-months after publication [1]. We should expect that immediate access from PMC would divert an even larger share of readership from journals, further diminishing their value in the eyes of academic subscribers.

1. Davis, P. Public accessibility of biomedical articles from PubMed Central reduces journal readership—retrospective cohort analysis. FASEB Journal (2013) 27:2536-2541. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-229922

Just my usual question, once more: is publishing (and its business plans) more important than research, or is research more important than its publishing phase? The answer is obvious and prioritizing the “sustainability” of publishers is simply addressing the issue from the wrong perspective. The print world did not give a d… about the sustainability of scriptoria and the same may well happen to present-day publishers if they stick to their obsession with “sustainability” (aka profit seeking).

The important point is that all the money of the system comes from essentially two sources: libraries and funding agencies. Reshaping the publishing and communication systems of research can be imagined by an alliance between these two groups. It can also be done either without journals, or with journals re-conceptualized as community-based instruments of communication. In fact, journals are an outdated legacy of print.

Well-designed, distributed, platforms organized by libraries and university presses would be much better to manage not the “versions of record”, but rather the “records of versions” (Kramer and Boesman). In so doing two things would happen:

1. publishing and communicating would be realigned; evaluation could be realigned with each other;

2. evaluation of research could be done independently of the processes associated with publishing and communicating.

Roy, thank you for bringing these revenue streams into the discussion. It is absolutely true that some journals will be challenged to replaced more than just the subscription revenue. It’s also important to note that in some cases, society high-impact journal subscriptions have lower subscription rates BECAUSE revenue is augmented by rights, licensing, and permissions (RLP) as well as corporate subscriptions from massive hospital systems, pharma, and financial institutions.

To Phil Davis’s point, the other hit to clinical journals is off-site content. Accepted manuscripts on PubMed Central with zero embargo significantly reduces journal website traffic, which affects digital advertising revenue.

As mentioned, the bulk of these journals are society owned journals. These journals also have a significant amount of invited content by way of commentary, context, and expert perspectives. An APC is not appropriate for this content and it’s not uncommon for these kinds of content to account for 25-50% of content in any given issue.

Lastly, it is not uncommon for papers to have pharma funding and federal funding. Pharma has a large interest in Gold OA publishing and has been investing in making their funded papers open in this way. In an Accepted Manuscript Zero embargo CC BY world, journals not only lose RLP revenue and corporate subscriptions, but also APCs from industry. With no guidance for how much federal funding is required for any given paper to be covered by the mandate, this is a huge free ride for corporate entities.

The myopic nature of this article and the fragility being displayed by my fellow commenters are frankly astonishing. This hand-wringing is similar to Mr Burns (ref: The Simpsons) or more appropriately Scrooge, complaining that we’re (ref: “society publisher clients hyperventilating”) just about sustainable and now the world is turning against us for making a business out of something that was never meant to be a business, by extracting value from a naturally occurring resource. This is not an anti-capitalist comment (call me socialist why don’t you?), so let’s split this out into its constituent parts. The journals themselves will be fine, tens of thousands of journals worldwide work fantastically well without being part of a profitable enterprise. They use the same raw materials and human resources as you do. So, there is a proven pathway to sustainability (see the world outside the gilded, rather expensive, echo chamber of the SSP conference rooms that have to be paid by someone… oh, it’s from the ‘cost’ of doing publishing, or more pointedly, from the revenues of publishing (count the attendees from individual publishers at Chicago this year, and also how many didn’t even turn up. With that much excess in the system, one must start to question it, no?). So, the threat is not to scholarly communications, the integrity of publishing, or the article of record. That really is dog whistle economics. The danger expressed by Roy in this article is to those who benefit from journal publishing as a business and as the driver of revenue. There will be unfortunate victims (for who I do have a great deal of sympathy) such as the huge sales teams, their very useful credit cards and open bars at ALA and Charleston, and the scholarly societies who will actually struggle to replace the millions of dollars each year to support their membership activities. But let us not weaponize the flip to say that it will affect the very fabric of research or the fundamental sustainability of academic publishing. It will not. What this affects is the business of publishing. Not publishing or scholarly communications. That will continue. What we see here is commercial fragility. And it’s disturbing that we simply gather around the watercooler and pour ourselves another cup of kool-aid in the Scholarly Kitchen.