In April, K|N Consultants (Rebecca Kennison of Columbia University Libraries and Lisa Norberg of the Barnard College Library) released a much-anticipated white paper titled “A Scalable and Sustainable Approach to Open Access Publishing and Archiving for Humanities and Social Sciences.”

It was much–anticipated in part because, wisely, Kennison and Norberg had provided public access to an earlier draft and solicited open comment; this had the twin effects of strengthening the final version and generating buzz about it. The paper is long—83 pages, including appendices—its arguments and proposals are detailed, and it comes with multiple sets of supporting tabular data. It is not a quick-and-easy read, nor are its proposals simple, but if one thing should be clear about the issues facing scholarly communication, it’s that quick-and-easy solutions are unlikely to be very effective.

At the beginning of the paper, Kennison and Norberg make it clear that their proposal is limited, in the short term, explicitly to humanities and social science (HSS) journals from nonprofit society publishers, on the assumption that author-pays Gold Open Access (OA) is likely to remain the OA solution of choice for publishers of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) journals in at least the short term. (The hope is that their proposed solution will expand to cover all disciplines in the long term.) Juxtapose the narrow focus of the proposal with its complexity and you start to see how daunting a task it is to revolutionize a system that has not changed in any really fundamental way since the first scholarly journals began to emerge in the 18th century. That Kennison and Norberg were willing to take on this task, have worked through the issues so thoroughly, and have come out on the other side of their process with such a carefully-considered proposal is a tribute to their energy, endurance, and thoughftulness.

The basic structure of Kennison and Norberg’s proposal is a three-way partnership between higher-education (HE) institutions (as funding bodies), libraries (as archives and distribution nodes) and scholarly societies (as gatherers, editors, and presenters of content). The basic idea is that HE institutions themselves—drawing on centrally-administered campus funds rather than library budgets—will make an annual contribution to a central fund, which will be administered by a not-for-profit entity to be determined in the future (though K|N Consultants suggests itself as a candidate). This fund would be used to underwrite the editorial operations of partner societies, freeing them from the need to charge subscription fees for their journals. Participant libraries would reallocate staff time from tasks previously associated with traditional subscription management to tasks associated with journal hosting and archiving. In the early stages of the project, private granting agencies will be solicited for matching funds to make the resource pool deeper and to mitigate the risk of early failure, making participation more attractive to HE institutions.

The nut of the proposal is captured nicely in this sentence: “By partnering with scholarly societies, libraries fulfill their mission to capture and preserve the intellectual capital generated by our institutions.”

Some readers may be alarmed (while others may be delighted) by the tone of the “Proposed Solution” section, which represents the core of the paper and at times sounds a bit like a stern nanny explaining, cheerily, why the unpleasant task you’re being required to undertake is going to make you and everyone else happier in the long run. The proposed model includes “a campaign in a stepwise but nevertheless assertive way to persuade all tertiary academic institutions to participate.” HE institutions “must be prepared to support new models of scholarly communication.” Libraries should brace themselves as well: “Resourcing these new services may require the transformation of many traditional library departments, as well as the roles and responsibilities of current staff.” Even those who agree with such ideas in principle may raise their eyebrows at the breezy, wand-waving tone of some of these pronouncements.

However, upon closer reading it becomes clear that this proposal does not actually contemplate the kind of centralized coercion hinted at by such language. In fact, those who wish to participate in the program will have to “apply for the funds through a competitive grant process,” one which is described in some detail in the white paper. The authors have no illusions that the entire population of publishers, institutions, and libraries will jump on board immediately; instead they propose what amounts to a proof-of-concept phase which they hope will demonstrate to the more tradition-bound and risk-averse members of those populations that this project can work and will benefit them.

I suspect that there will be lots of discussion of this proposal, and there’s a far greater number of things to say about it than I have room for in this posting. But here are a few points that jump out at me. I will present them in three categories: Kudos, Caveats, and Questions.

Kudos

- The project appears to be scalable: this model seems feasible at the scale of one institution with one or several society partners, and remains so at the level of hundreds of institutions with hundreds or thousands of partners. That aspect of this proposal is huge and should not be overlooked.

- It seems, broadly speaking, fiscally realistic: this model is not built on fantasy scenarios about the cheapness of digital scholarly publishing, spun by people who have never done it. Because publishers themselves would be intimately involved with its implementation, there is relatively little risk of the program proceeding without a realistic perspective on the real-world costs of journal publishing.

- It brings libraries’ host institutions into the mix. One of the problems with the current scholarly communication marketplace is the structural disconnect between supply and demand and between choice and consequence across multiple dimensions. Assessments at the campus (rather than the library) level create a closer connection between choice and consequence.

- The proposal is for phased and incremental implementation, “acknowledging the inherent conservatism of academia.” Academics hate it when you call them “conservative,” and that can make it hard for consultants to talk about the reactionary tendencies of academic culture (which are often amplified in the library realm). Kudos to Kennison and Norberg for calling it out and dealing with it explicitly in their proposal.

- The model is designed and intended to be flexible, to “support scholarly communication infrastructure, rather than specific packages… projects, or platforms.” The authors’ hope and intention is that, as new models of scholarly communication develop, this model will be flexible enough to accommodate them.

- The proposal recognizes the important point that historically, publishers have served primarily as disseminators, not as preservationists and archives. The latter functions have been more or less forced on publishers with the advent of the World Wide Web, and the fit has never been comfortable. One significant benefit of this proposal is that it could relieve publishers of the preservation and archiving role and shift it to libraries, where it is much more in harmony with historical mission.

- The authors continue to solicit discussion of the ideas and proposals contained in this white paper, and provide multiple avenues for doing so, both public (via Twitter, interestingly) and private (via email).

Caveats

- The assessment model is intended to result in institutional charges that are “modest relative to the overall budget,” but the proposed charges are not indexed to institutional budget. Instead, they are based on the number of students and faculty. The formula therefore introduces anomalies that many potential participants will find hard to swallow. For example, the model proposes annual charges of $366,890 to Arizona State University, $86,430 to Bowling Green State University, and $143,930 to Utah State University. Princeton, on the other hand, would pay $39,875, Dartmouth would pay $31,385, and Duke would pay $76,930. Harvard’s payment, though at $140,735 substantially higher than Princeton’s, would be $13,000 lower than that of Colorado State University. The authors portray their assessment model as representing “the price of a cup of coffee per year per student and faculty member,” but those cups of coffee add up to an annual charge of multiple hundreds of thousands of dollars for many cash-strapped HE institutions and only tens of thousands for some of the richest ones. This seems like an odd strategy for a program that claims “fairness” as one of its core guiding principles.

- Too many of the foundational arguments in this document are rhetorically powerful but logically questionable. “Restricting access to research benefits no one,” for example, is a time-tested applause line, but it artfully obscures the more difficult fact that charging for access to research certainly does benefit many—even as it creates problems for others. Similarly, pronouncements like “it is hard to imagine how greater access would not be welcomed by a society’s membership” and “subscription-based publishing models… often (put) the society’s publishing operation in conflict with their members’ desire for unfettered information exchange” involve both question-begging and the reduction of complex realities to convenient but oversimplified bromides. (More on this below.)

- Although the proposed funding model is manifestly scalable in purely fiscal terms (since more participants means more funding support), there is a problem with it in terms of staff support. The authors suggest, for example, that library staff currently focused on”serial acquisitions and subscription maintenance… be deployed to assist with society or partner relationships,” and that “systems staff involved in maintaining authentication systems could tackle new infrastructure development.” The problem here is that even if all HSS journals were simultaneously to shift to the proposed model, most or all of the STEM journals (not to mention research databases) would remain, for at least the short- to mid-term, under the old subscription regime, meaning that the library staff in question would still be needed to manage subscriptions, maintain authentication systems, etc.

- Another weakness in the funding model is that it is “based on an annual or multi-year payment made by every institution of higher education… and by any institution that benefits from the research that is generated by those within the academy” (emphasis mine). To the degree that universal adoption is truly fundamental to the model, the model is in trouble. It’s hard to imagine a voluntary program of any kind, no matter how broadly the HE community may agree with its goals, being universally accepted by HE institutions—let alone a program that requires what are often significant annual payments and redirection of staff time. That said, however, I’m not sure that universal adoption truly is fundamental to the model; it looks to me like it could function and have at least some of its intended impact even with only limited uptake.

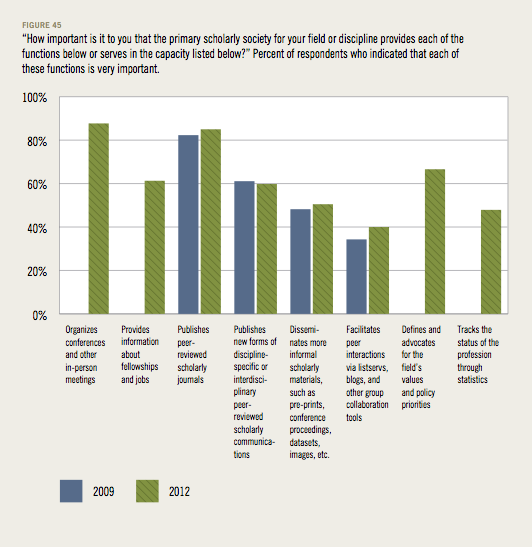

- In support of their proposal the authors assert a general desire on the part of scholars for “unfettered information exchange,” but provide little or no support for the assertion despite the fact that the existence of that desire is central to the value proposition of their program. Notably, their characterization of the findings of Ithaka S&R’s 2012 Faculty Survey makes it sound as if scholars chiefly value their societies for the role they play in facilitating “exchange of information with their peers,” but that is a misleadingly oversimplified gloss on what the survey actually found. As demonstrated in the figure at right (click to enlarge), the survey found that faculty members place by far the greatest

value on their societies’ roles as conference organizers and as publishers of formal, peer-reviewed journals. “Unfettered information exchange” is already available to any scholar who wishes it; what is not available on a free and unfettered basis is the exchange of information that has been peer-reviewed, edited, formatted, permanently archived, etc., for the simple reason that these services cost money and someone has to pay for them. What the survey findings indicate is that formal publication programs (and the conferences that are typically underwritten by the selling of access to those publications) are of great value to the scholars surveyed, and they want their societies to play a major role in providing it.

value on their societies’ roles as conference organizers and as publishers of formal, peer-reviewed journals. “Unfettered information exchange” is already available to any scholar who wishes it; what is not available on a free and unfettered basis is the exchange of information that has been peer-reviewed, edited, formatted, permanently archived, etc., for the simple reason that these services cost money and someone has to pay for them. What the survey findings indicate is that formal publication programs (and the conferences that are typically underwritten by the selling of access to those publications) are of great value to the scholars surveyed, and they want their societies to play a major role in providing it.

Questions

- Is academia’s appetite for immediate free access to HSS content strong enough to generate a willingness to pay the annual fees proposed? In particular, where the institution’s annual fee would be relatively high and its mission is relatively focused on the STEM disciplines, it seems as if participation would be a hard sell. This suggests that instead of indexing the institutional charge either to student/faculty populations or to overall institutional budget, an even better approach might be to index it to the number of students and faculty working in HSS disciplines.

- The model explicitly considers “university presses to be similar entities to societies,” arguing that they, “like societies… struggle with the tension between their mission to make information widely available and the very real requirement that they be financially viable.” Furthermore, the authors assert that “university presses are quite often thought as peripheral to the core activities of most faculty.” But I have to wonder whether most UP directors would agree that “(making) information widely available” is itself a core part of their mission and whether faculty (who, especially in HSS disciplines, are generally required to publish scholarly monographs) would agree that UPs are “peripheral to (their) core activities.” These questions are worth exploring.

- The model is built on the assumption that libraries will be willing to substantially reorganize their technical operations and that universities will be willing to “redefine the roles that (libraries) play within their organizations” in order to accommodate this new system. Will colleges and universities agree that universal free access to HSS articles is worth this cost?

- If Gold OA does not, in fact, take hold as the universal solution to access in the STEM realm, will HE institutions then be left with libraries that have been substantially reorganized to make HSS content freely available, but are no longer in a strong position (organizationally or fiscally) to enable access to STEM content? At liberal arts colleges this may not be a big deal; at comprehensive and research universities, it certainly would be.

- The white paper acknowledges but never seriously addresses the “free rider” problem—one that is intensified by a funding model that asks much of meagerly-funded institutions and relatively little of wealthy ones. The likelihood that richly-funded institutions like Harvard and Princeton will opt for the free ride is relatively low, whereas the likelihood that Arizona State and Colorado State (with their much larger student populations) will do so is quite a bit higher. Unfortunately for the tenability of the model, there are very few Harvards in our HE community and many, many Colorado States. The urgent question, then, is whether this model can provide concrete, structural incentives (as well as moral ones) to the Colorado State Universities sufficient to keep them in the system.

This has been a long (and probably tedious) posting and it has only scratched the surface of the questions and issues that are likely to be raised about this white paper. I hope that I haven’t misunderstood or inadvertently misrepresented any of it; if I did, I invite correction. I’ll close by repeating my praise of Kennison and Norberg for the industry and courage they’ve shown in producing it, and by expressing my hope that the discussion will be broad-based, constructive, and productive of real and beneficial change—which is, of course, the only kind of change any of us should be hoping for.

Discussion

58 Thoughts on "A Modest Proposal for Scaled-up Open Access"

I’ll read the paper in its entirety later this week, but let me get this straight — if HE institutions pay more than they are now for HSS publications both directly (through fees) and indirectly (through library management of archives), and publishers pay less (don’t pay their editors and don’t pay for archives), then the model can work. Is that the proposal in a nutshell?

In addition, rich private institutions would often contribute less than modestly funded state schools?

And it’s all voluntary?

So, it’s more costly, seems to mainly benefit publishers, is no more scalable than the subscription model, is potentially inequitable, and nobody has to do it?

Exactly who will support this idea in the real world?

In fairness, I should point out that if this model were fully implemented, a great number of HE institutions (the smaller ones with low enrollments) would almost certainly end up paying less in fees than they are currently paying in HSS journal subscriptions.

But your fundamental question is a good one. I have to say that I have a hard time imagining that many provosts and VPs for research would be very excited about signing on to this project.

The other aspect not addressed in your summary is overheads. The consultants propose themselves as the non-profit running this payment system, but they’d only do that if it made them fairly comfortable. That implies overheads. What is the expense of another layer of payments and payment monitoring and payment handling?

Hmmmm. A pricing model developed centrally from a formula. Didn’t the USSR try this?

I find your post the opposite of tedious, Rick. As for the proposal it is rather amusing to see a utopian scheme priced to the dollar, but helpful as well. To begin with there are already a lot of HSS journals paid for by schools, so the proposal is mostly about scaling up to a centralized system. Here two basic issues arise. The first is who decides what journals get, or continue to get, published, and how do new one’s arise? Centralized systems of production tend to impose central control of production, unlike both subscription and gold/APC OA, which are both market based.

The second issue, which you allude to, is the cost of the transition, which can be quite high and is often the reason change does not occur, or occurs very slowly. Estimates of steady state unit costs tend to grossly underestimate the cost of change.

Also, regarding your report that this all depends on gold/APC OA taking over the STEM world, it is indeed problematic. Just last week Kent had a big article on why this takeover is very unlikely, especially given the emerging US Public Access program of delayed green OA. Thus this grand proposal may already be OBE, at least in the US.

I would never just assume I could step in and do the job of a highly trained library science specialist. Why do the authors of this proposal think that a librarian would be able to do mine?

This is a problem we have in my profession, to be perfectly candid. I think that we librarians have a general tendency to greatly underestimate the costs involved with publishing a rigorous, peer-reviewed journal — especially in the sciences.

I thought the scholarly societies were still publishing the articles, although the library might handle the Website.

Rick,

Thank you for your careful, thoughtful gloss on this new proposal. Can you tell me why the Colorado States of this world would pay for this when much of this content will be available for no additional charge after the embargo period in a Green Open Access model?

Setting aside the fairness of ASU paying heaps more than Harvard, perhaps the reasons why any schools would be willing to shell out so much money is that it might cost less than their subscription packages to the societies and the databases/indexing services that host and organize the content.

I say MIGHT because a) I haven’t read this proposal in its entirety yet and b) I don’t have a way of knowing how much ASU (or any other school) pays for their HSS subscriptions.

Rick, as a Library Assoc. Dean, can you tell us (in ballpark terms) how the proposed K|N price for Utah stacks up against the price you’re currently paying for HSS content?

Under the model, my institution would pay $161,940. I’d have to do some collection-crunching to figure out how that compares to what we’re currently paying for HSS journal subscriptions, but it’s probably less — so if every HSS publisher got on board, our campus would probably save some money. Well… except for the fact that under the proposed model, the library itself would save money no matter how many publishers participated, because the money isn’t supposed to come from library budgets. So participation would result in a net increase in expenditure for the campus as a whole, unless the campus said “Fine, we’ll participate, but we’re going to reduce the library’s allocation accordingly.” That’s not what Kennison and Norberg have in mind, but I don’t see how they could stop it from happening. Hmmm.

I should also point out that indexing databases are not covered under this proposal, and would still be available only by subscription.

Per your budget guesses–that’s helpful information to have, thanks for sharing.

My point about indexing databases is that were the information easily findable online, libraries might not see the need to buy subscriptions to them anymore. But that’s an extrapolation beyond the scope of what you’re talking about in this post, I agree.

The thing is, most of the information contained in those databases is already easily available online regardless of whether or not the articles themselves are freely available. And (as you suggest) libraries are generally subscribing to fewer such databases as a result — though many of them do still provide pretty good value for money by making it easier for researchers to conduct discipline-specific searches. I don’t think those databases have a very bright future, though, regardless of what happens with OA.

I echo your kudos to Rebecca and Lisa for their work on this paper, Rick – and kudos to you too for distilling it into a single blog post! It’s an interesting concept, but I find it hard to believe that, for now anyway, anything like enough of the key stakeholders – institutions, societies, researchers – think that the system is so broken for HSS scholarship that they’re prepared to risk the disruption (and, at least in the short term) expense.

“Because publishers themselves would be intimately involved with its implementation, there is relatively little risk of the program proceeding without a realistic perspective on the real-world costs of journal publishing.”

Just an amber light flashing here … it strikes me that this is more or less identical to saying “Because publishers themselves would be intimately involved with its implementation, there is relatively little chance of the program realising anything close to its potential savings”.

Born-digital publishers have shown not just in the theory but in practice that it’s possible to do academic publication with all the trimmings for an order of magnitude less than legacy publishers have been used to charging. To me, that’s a strong argument for avoiding the involvement of legacy publishers, who will surely come up with arguments from somewhere to justify their high costs.

To me, that’s a strong argument for avoiding the involvement of legacy publishers, who will surely come up with arguments from somewhere to justify their high costs.

Under the proposal, participating publishers would not charge anything at all for access to their publications. Are you anticipating that they would come up with arguments to increase the payments distributed to them from the central fund? (And if so, then isn’t that an argument against any OA publishing model whatsoever, or at least any model that involves traditional publishers?)

Yes, I am anticipating that; and yes, it does seem to be an argument against the involvement of legacy publishers in Gold OA. Of course, if they can compete (on a level playing field) on price and service, then good for them.

What’s proposed here is really a variation on what we’ve traditionally understood to mean “Gold OA.” Have you read the proposal itself yet?

I admit I have not. I’m sensitive to publishers telling people how much they ought to expect to pay, because I saw that exact mechanism hijack the Finch report.

When you read the proposal, you’ll see that it does not involve publishers telling people what they ought to pay. It involves OA advocates telling publishers how much they can expect to be paid.

That is very good news — but you can see why I didn’t leap to that conclusion from the passage that I initially quoted.

Hi Rick

Thanks for this. Your explanation raises questions, but perhaps the white paper answers:

a) if one reads the larger discussion on the HEI’s, it is projected that many of these will not be in existence in their current embodiment in the relatively near term, particularly those that are less well endowed. In a similar vein, outside of the EU and North America, many developing country institutions are in a similar situation where fiscal resources are scarce.

This, of course, seems to argue that there will be a core of institutions where resources to support publishing will become problematic along with concomitant arguments.

The model has the same ring that the US health insurance program has. It requires significant participation to amortize the over all costs.

b) No one has indicated what such a model will do to the business model of the societies and non-profits where income from the current subscription model, in many instances is not just plowed back into the journals themselves but used for the society’s larger purpose in the same manner that the for-profit publishers use the net returns for stock holders.

c) The graph that you posted shows that there was a significant preference for PEER reviewed activities from conferences to publications. Underlying all this is the much avoided issue of promotion and tenure in academia where the value of the document is in its being “vetted” rather than in the significance of the content. Perhaps the academic institutions, under this model will reassess the cost to the institutions of their faculty and their oeuvre.

It is interesting that a number of funders, largely in the biological and health arena are most concerned about the stacking of research findings with seemingly insufficient theory to practice. The humanities have been hoisted by their own petard if one recalls the Sokal affair.

No matter how the costs are sliced and diced and redistributed, the number and cost/publication is rising. Maybe one might want to build a pricing model based on quantity?

a) if one reads the larger discussion on the HEI’s, it is projected that many of these will not be in existence in their current embodiment in the relatively near term, particularly those that are less well endowed.

It’s certainly true that this model is built on the assumption that the great majority of HEIs (in the U.S., anyway) will remain financially viable for the foreseeable future. That said, the institutions that most commentators seem to feel are most at risk are the ones that would contribute least to the central fund under this model, so that might alleviate the risk somewhat.

b) No one has indicated what such a model will do to the business model of the societies and non-profits where income from the current subscription model, in many instances is not just plowed back into the journals themselves but used for the society’s larger purpose in the same manner that the for-profit publishers use the net returns for stock holders.

It seems to be the authors’ intention that these revenues would be replaced by allocations from the central fund. One thing that does not seem to be addressed in the model, though, is whether there would be an allowance for any kind of annual growth in those allocations. If a society’s membership (and therefore the cost of its conference and other services) grows, how will it meet those growing costs if it depends on a static annual allocation?

c) The graph that you posted shows that there was a significant preference for PEER reviewed activities from conferences to publications. Underlying all this is the much avoided issue of promotion and tenure in academia where the value of the document is in its being “vetted” rather than in the significance of the content.

I think this issue gets discussed quite a lot, actually — in fact, last week there was quite a bit of discussion about it here in SK (in the context of altmetrics).

No matter how the costs are sliced and diced and redistributed, the number and cost/publication is rising.

OA advocates — whose proposals (including the one discussed above) are usually based on the assumption that publishing doesn’t or shouldn’t cost much — tend not to accept that premise.

I have not yet had time to digest the full proposal so am largely relying on your thorough write-up. That said, it seems like there is an unnecessary level of complexity introduced here. If the goal is gold-OA (and leaving aside for the moment whether green/delayed-OA might be a better approach for HSS content), why not just ask each institution to set aside funds for APCs? If there is a concern with paying APC’s to commercial publishers, then why not simply invest in the existing university presses? Any scheme that requires universities to set aside central funds in perpetuity, libraries to repurpose staff, society publishers to covert existing revenue streams to a new business model with shaky (at least at first) funding, funding bodies to supply various grants, and a new central administrative body strikes me as too complex to ever get off the ground.

If the goal is gold-OA (and leaving aside for the moment whether green/delayed-OA might be a better approach for HSS content), why not just ask each institution to set aside funds for APCs?

Some institutions are doing this, but mostly it’s happening in libraries rather than at the institutional level — for the simple reason, I think, that librarians tend to care a lot about OA and campus administrators tend not to. The problem, of course, is that libraries are not generally in a position to set aside enough APC funding to make much difference, at least on a STEM-focused campus. In my library, when we set aside $20,000 to underwrite APCs, the result was that we made somewhere in the neighborhood of 12-15 articles freely available to the world. When you compare that outcome to the amount of content that we could have made available to our local students and faculty at the same cost, you can see the difficulty.

The fact that campus administrators tend not to care much about OA presents what may be the single greatest stumbling-block for this proposal (and for most OA proposals, frankly).

If there is a concern with paying APC’s to commercial publishers, then why not simply invest in the existing university presses?

Same answer.

Since IHEs are both the primary producers and consumers of scholarly communication, this circumnavigation of a legacy market with tolls to pay at every stop seems incredibly wasteful in this digital age. Collectively, IHEs also possess or can recruit all the necessary means of production in this market so why not bring it all into an IHE-funded consortium?

Since IHEs are both the primary producers and consumers of scholarly communication, this circumnavigation of a legacy market with tolls to pay at every stop seems incredibly wasteful in this digital age.

Sorry, by “this circumnavigation” do you mean the current toll-access system or the system outlined in the K|N proposal?

Collectively, IHEs also possess or can recruit all the necessary means of production in this market so why not bring it all into an IHE-funded consortium?

That’s pretty much what’s being proposed in the document under consideration here. But I think the short answer to your question is that HE institutions aren’t particularly interested in taking over scholarly publishing. The current system amounts, basically, to outsourcing: HE institutions provide the content and some of the editorial work, and pay external publishers (most of them nonprofit societies, some of them for-profit publishers) to do everything else. Libraries are increasingly dissatisfied with this arrangement and some faculty members agree with them, but as far as I can tell most faculty members think it’s fine and campus administrators feel the same way. Hence the elements of the proposal that talk about “a campaign in a stepwise but nevertheless assertive way to persuade all tertiary academic institutions to participate.” The unspoken assumption behind those elements is the fact that campus administrators are not exactly lining up to help dismantle the existing system.

Perhaps this is a minor point but a significant amount of research is done by institutions, organizations, firms and people other than HE. Thus scholarly publishing is not really just a case of HE outsourcing. Nor are HE libraries the only subscribers. This also tends to make this HE-centered proposal unrealistic.

The circumnavigation that I was referring to was the current toll-access system.

Regarding faculty and administration, I think that your assessment is correct. There’s generally not a great inclination to change because, I think, that would require vast cultural change and no one in HE seems to have any viable alternatives to put forth. For example, the promotion and tenure process would have to be reformed so that the assessment of scholarly work would not have to be outsourced to publishers. The preference is that things will continue as they always have. No one will have to change their behavior.

Whether IHEs can continue to be so inefficient with costs rising faster than housing and health care will probably carry more weight than the preferences of faculty and administration. Public IHEs are already feeling the heat of legislative scrutiny and consequent reduction in subsidies. The squeeze is on.

The circumnavigation that I was referring to was the current toll-access system.

In that case, I’m not sure I see what you’re talking about. The current system doesn’t involve anything that I would characterize as “circumnavigation… with tolls to pay at every stop.” Under the current system, HEIs and granting agencies pay faculty to do the research and some of the editorial work, and subscribers (notably libraries) pay publishers to do other parts of the editorial work and to disseminate and archive the results. It’s not that complicated; everyone who contributes to the process gets paid by someone. The controversies arise not because the system is complex, I think, but because many subscribers feel that publishers charge too much, and because some people feel that publishers shouldn’t be involved at all.

“The controversies arise not because the system is complex, I think, but because many subscribers feel that publishers charge too much, and because some people feel that publishers shouldn’t be involved at all.”

You surely know that that’s not where the controversy is for many of us. The issue for me and for many other OA advocates is not how much publishers charge or that they exist at all, but that the revenue model is based on denying access. Fix that and all is well. (Or at least, the conditions exist for all to be well, as a real market will exist for publishers to compete in, rather than the present set of little monopolies.)

Sorry, when I said “publishers shouldn’t be involved at all,” I should have said “toll-access publishers shouldn’t be involved at all.”

That said, I’ve never accepted the formulation that “the revenue model is based on denying access.” That’s a ridiculously tendentious turn of phrase — it’s like saying that restaurants stay in business by making sure people don’t eat, or that the salary structure for college professors is based on denying students access to education. In all of these cases the actual intention and desire of the provider (whether it be a publisher or a restaurateur or a college) is for people to have access — and to pay for it, so that they can continue to “stay in business” (a phrase that has a slightly different meaning in each of the above contexts). That has never seemed to me like a fundamentally unreasonable deal, though the details — such as price — may be cause for disagreement.

That said, I’ve never accepted the formulation that “the revenue model is based on denying access.” That’s a ridiculously tendentious turn of phrase.

Not at all. When I say that I’m not trying to get a reaction or rouse a rabble, I’m honestly stating how the world is set up. You have publishers that make their money however many copies of their articles circulate (BMC, PLOS); and then you have those that will lose money if many copies circulate (Elsevier, ACS). It is simply not credible to claim that the latter will not try to prevent access — neither is it compatible with simple observation of how they actually behave.

It’s like saying that restaurants stay in business by making sure people don’t eat.

I am genuinely surprised that you would try to make such an analogy. We both know that it is completely inapplicable for the usual reason when discussing information economies: the marginal cost of each meal a restaurant serves is significant; that of each copy of a published article is zero. Trying to apply analogies from one kind of economy to the other is foolish: I really didn’t expect to see it here.

If you really want an open-access analogy based on food markets, you’ll find one here. Note that it can only be made to work by bringing in a science-fictional premise.

Mike, no comment about the food biz, but you are simply wrong about the structure of the economics for OA and traditional publishing. Traditional publishers make MORE money the more people who access their paid material. OA publishers get more money from the number of articles they publish. It’s fundamentally different. Over time this will result in the two kinds of publishing, including the content itself, becoming increasingly different. Nothing inherently good or bad about any of this. It’s just different.

You’re right that my restaurant analogy doesn’t work — fair point. Nevertheless, the statement that “the revenue model is based on denying access” is still misleading and tendentious. The fact that access is restricted to those who pay may be a necessary aspect of the traditional revenue model, but it is hardly the basis for it, since denying people access creates no revenue. Publishers make no money at all when someone is denied access; they make money only when someone gains access (and pays for it). So it would actually be much more accurate to say that the revenue model of traditional publishing is based on getting information into the hands of as many people as possible — as long as they’re paying.

OK, let’s agree to pretend the restaurant analogy never happened 🙂

On the more substantive point that “the revenue model is based on denying access”. You concede that “access is restricted to those who pay”; isn’t that exactly logically equivalent to “to those who do not pay, access is denied”? [(P ⇒ Q) => (¬Q ⇒ ¬P)]

Or to put it another way (as I did in a blog-post almost exactly a year ago about three publishers suing the University of Delhi): “As soon as a publisher has a paywall, its mission and its business are in conflict. A paywall-based publisher cannot both advance its mission and preserve its revenue.”

You concede that “access is restricted to those who pay”; isn’t that exactly logically equivalent to “to those who do not pay, access is denied”?

Absolutely; we agree on that point. Where we disagree is when you leap from that statement to the conclusion that “the revenue model is based on denying access.” That jump is unjustified; it confuses a merely necessary condition (the ability to restrict access) with the fundamental process by which revenue is generated (granting access in return for payment). In other words, it’s true that “to those who do not pay, access is denied.” It is not true that denying access to those who do not pay generates revenue for the publisher. The only thing, in fact, that generates revenue for the publisher is people getting access (and, of course, paying for it). As more people gain access under this model, more revenue is generated for the publisher; if more people are denied access, less revenue is generated.

To be clear here, I’m not defending the traditional publishing model. There are good things and bad things to be said about it. I’m just objecting to a misleading characterization of it.

We’re playing with semantics now; that’s fine by me — I enjoy such manoeuvring — but I won’t blame anyone else who chooses to tune out!

In other words, it’s true that “to those who do not pay, access is denied.” It is not true that denying access to those who do not pay generates revenue for the publisher.

Will you not agree that allowing access to those who do not pay reduces revenue to the publisher? If so do agree, then I think you’re agreeing with my previous statement, which is logically equivalent; if you don’t, then why don’t publishers simply allow access to everyone, secure in the knowledge that it won’t reduce revenue? To me, the fact that they don’t do this is solid evidence that the statement is true.

Will you not agree that allowing access to those who do not pay reduces revenue to the publisher?

Yes, but then you’re not allowing access under the revenue model, and therefore this statement is not logically equivalent to the statement under discussion. The revenue model is one by which people pay and get access. (It’s also true that those who don’t pay don’t get access — but denial of access is not a revenue-generating mechanism, and therefore can’t reasonably be called the basis of the revenue model.)

The K/N proposal, as described by Rick Anderson, sounds almost as hallucinatory as the SCOAP3 proposal, since both are based on voluntary contributions. Are there any examples of successful business ventures that rely solely on voluntary contributions?

Our thanks to Rick Anderson for his thoughtful and constructive summary of our proposal, as well as his engaged responses to many of the same comments and questions we have and continue to grapple with. We look forward to continuing the conversation.

It’s always good to have fresh thinking about how to make OA work, and focusing on HSS in particular is valuable because so much of the attention hitherto has been focused on the STEM fields instead. That said, I have concerns that partly mesh with Rick’s but also expand on some of them. The model proposed seems to contemplate the fees charged to HEs covering the basic costs a society incurs in running a journal operation. But this model would then omit a crucial characteristic of the economics of what is now happening., viz., that societies generally want to make a profit on their journal subscriptions so that they can use those profits to fund other activities the society considers important. (University presses also generally make profits from their journal operations that are used to subsidize their monograph publishing. This is true even for smaller presses like Penn State where I was director.) So, if this is so, why would any such societies find this new model attractive? Ignoring university presses also seems like a huge mistake. After all, those presses collectively account for publishing over 1,000 journals in the HSS fields, some of which they are publishing under contract with societies. To answer Rick’s question about mission, yes, university presses generally view wide distribution of knowledge as a key mission: one of the most often quoted comments on what university presses do came from Daniel Coit Gilman when the Johns Hopkins Press was founded “to distribute knowledge—far and wide.” This is one reason that presses typically have sold their books and journals for much less than their commercial counterparts, as revealed through the studies done by Fordham professor Al Greco. Presses, however, have to balance this mission against the economic pressures of remaining viable businesses–which is why they have not advanced farther than they have down the road of OA publishing. Finally, I would emphasize the severity of the “free rider” problem. Recall that the Report of the National Enquiry into Scholarly Communication way back in 1979 recommended that all universities help support the system more than they were doing, and if they didn’t have presses of their own, help contribute to the costs of running those at other universities. This recommendation went nowhere, and universities simply continued to rely, as free riders, on the 80 or so U.S. presses that other universities supported. Why should we expect any different outcome now?

I am surprised that no-one here has commented on the pretty fundamental problem – from an academic and learned society point of view – of the notion of a central planner that collects and distributes all the funds. For all its other defects, one of the great virtues of the present ecosystem is that it offers diverse opportunities for journal start-up and an independent source of revenues for learned societies, in addition to members subscriptions. Once there is a central planner, innovations are only possible when the planner’s advisers approve of the project – rather than having a range of competing publishers to approach. Learned societies become vulnerable to external leverage on their behavior rather than being member-controlled associations – Finch could not understand why UK learned societies did not just roll over and accept UK government policies on OA in the way that UK government agencies had done, for example. Diversity in revenue streams is absolutely fundamental to the independence that makes scholarly innovation possible.

In many ways Sandy Thatcher’s and Robert Dingwall’s responses, coupled with my earlier post point out that journals are embedded in a complex system within and across those entities that own/produce journals.

Of greater concern to the larger system is the recent demonstration of IBM’s Watson now able to rapidly scan and even analyze to the point of creating a pro/con debate on almost any subject. This points out that the current proposition and the arguments in this thread are based, basically, on the system that was/is extant and how to deal with current problems. It is historic preservation rather than responding to what happens in the world of “big data” and HAL’s off-spring now on the desk of every scholar indifferent to whose collection contains the data or where archived on some large server farm curated by Amazon.

This impacts well beyond the publishing, distribution and curating but on the function of the current libraries as they now exist. Struggling with the K/N proposal is fighting ghosts of “Christmas past/present” and not the future. Think of an article tagged with standard key words with the added “badge” from a vetting source and accessible almost instantly, weighted for a decision, not just life/death in an operating room but most modestly in the HSS arena.

The K/N proposal is DOA for all the concerns expressed, above, and the fact that this is solving a past and not a future that is becoming increasingly visible.

I would like to see this proposal go forward exactly as outlined, with the consulting team responsible for the proposal in charge of running the project.

Hi Joe,

Let me amplify on my comments just above yours with this short analysis. I don’t htink it is “bearish” but points to the fact that the future will not be lke the past, even near term.

Exploring the Myths of the Past to See the Future

Tom P. Abeles

Prologue

The Scholarly Kitchen, a blog on scholarly publishing, there is a link to an interesting story. Basically, there is a future where there is an ability to take farm grown food, clone it electronically and distributed to all globally. The result is an entire industry that previously provided packing and transport became superfluous. That was the case until they pointed out that their key value beyond the transport was to effectively screen the quality of the products so that people would be assured of what they were getting. Thus, collection and transport removed, the critical function was vetting what was being received.

Today there are farmers who raise a variety of produce and others who specialize not just on a single crop and even special varieties. Academic publications have some of this differentiation from general articles to focus on specific disciplines and subdisciplies.

Changes in Scholarly Publishing

Like farming, the academic publishing industry from commercial ventures to specialized societies have much the same flavor as agriculture. And as with the farming metaphor, the rise of the Internet, very large data basis and very rapid and intelligent search engines are starting to create stunning parallels. With careful use of key words and even “badges” or other vetting mechanisms, Fast adders* such as IBM’s Watson are able to pick singular articles of various ranks or certification, assess the content based on a researcher’s needs and even develop a synthesis of the materials from a host of articles in very short time intervals. Similarly the reverse can hold where a researcher has needs to distribute findings and needs an appropriate venue. All of this can be done by accessing databases sitting on server farms curated by parties such as Amazon.com

At the present, the food system is pure science fiction with a patina of near term reality. On the other hand, the model of academic publishing sans the political, social and economic arguments is here today in a testable form. An author could search all of the estimated 25,000+ journals and rank the most likely party to vet the work. On the other hand, a researcher setting a search strategy may find, across these same journals, materials that are critical and yet not found in the limited search of traditional sources.

As with the farmer analogy, all roles and economics change from those who own selective vetting sources (journals) to the academic libraries and the entire distribution system. The beneficiaries are the scholars who use these traditional systems to create, distribute and access each other’s materials.

* an adder is a deadly snake on one hand and on the other it’s the fundamental building block that makes all computers work

Reblogged this on Libraries are for Use and commented:

The proposal was presented at the OA Symposium at UNT-HSC. This posting did a pretty good job of describing it and the comments were all addressed at this presentation.