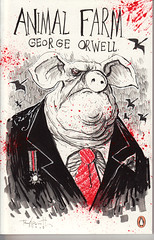

- Image by ben_templesmith via Flickr

Recently, Amazon‘s ability to remotely wipe purchases from the Kindle was put into the spotlight when the company deleted unauthorized copies of George Orwell’s “1984” and “Animal Farm.”

Oh, the irony.

According to David Pogue of the New York Times, the publisher changed its mind about offering electronic versions of the books, and Amazon deleted them from the accounts of anyone who had purchased them.

In a follow-up story a few hours later, Amazon apparently had a different tale to tell, stating that the books deleted were unauthorized copies, posted by someone without the legal authority to publish the books. Amazon refunded everyone’s money when they deleted the unauthorized copies. Note that the Kindle’s terms of service do not give Amazon the right to delete already purchased books from customers. Amazon’s ability to retroactively change the terms of the deal with no notice should give pause to anyone considering buying e-books on their platform.

Think of all the problematic scenarios this opens:

- What happens if you live in a country that decides to ban a book you’ve purchased?

- Can Amazon delete any text from your books that it decides is objectionable? What if Rupert Murdoch buys Amazon and wants to remove all purchased copies of a biography that paints him in a poor light? Should a religious movement have the right to delete all readers’ copies of The Satanic Verses?

- What if Amazon decides they’re not making enough money from the platform? Could they hold all of your purchases for ransom, demanding you pay extra to retain your “ownership”?

You’ll note I put “ownership” in quotation marks. As Bruce Schneier points out in the NYT article:

It illustrates how few rights you have when you buy an e-book from Amazon. . . . As a Kindle owner, I’m frustrated. I can’t lend people books and I can’t sell books that I’ve already read, and now it turns out that I can’t even count on still having my books tomorrow.

(For those who don’t think this is a big deal, all I can say is that we are at war with Eurasia. We have always been at war with Eurasia.)

Amazon has vowed not to do this again (“We are changing our systems so that in the future we will not remove books from customers’ devices in these circumstances,” an Amazon spokesperson said).

Amazon is coming off amateurish and ill-prepared as they continue to make misstep after misstep in this fledgling market. For a company that’s built up a great deal of goodwill and positive reputation with its customers, it’s surprising to see it both floundering and repeatedly taking actions against its strongest supporters. Amazon needs to get its act together before it sours the public on the concept of e-books, ruining this nascent market for the rest of us. Some suggestions:

- Rewrite the terms of service and be upfront and open about what it means when you “purchase” a Kindle book. No more hidden restrictions on downloads and clipping. Each book needs to list the specific terms under which it’s offered so buyers can make an informed choice and not feel like they’ve been ripped off after you’ve taken their money.

- Once you’ve got those clear terms in place, make sure all of your employees understand them. The contradictory information given both to customers and to the press is embarrassing and harms Amazon’s credibility.

- Provide an upgrade path for your customers. If you’re in the business of selling devices, you want your customers to continuously upgrade to the newest and latest versions.

- Vet your marketplace. Apple has been much maligned for the way they scrutinize every single app they approve for their store, but a process like that would have saved Amazon a lot of bad publicity here. Make sure the people you’re allowing to sell books actually have the rights to do so before you put them up for sale.

- Of course I’d suggest eliminating the customer-unfriendly DRM, but that’s an argument for another day.

As the folks at Boing-Boing point out, pulling the rug out from under your customers, hiding restrictions, and stealing back books you’ve already sold are the kinds of things that drive law-abiding consumers to find alternative illegal ways to obtain content. In the case of Orwell’s work, this is trivially easy due to Australian copyright law.

One other thought–Amazon could take a lesson from the New York Times. When David Pogue’s initial post on this topic proved incomplete, instead of making it disappear, they added an editor’s note linking to the more complete news story they’d produced.

That’s how you make digital publishing seem less like 1984.

Discussion

16 Thoughts on "Deleting Books — A New Kindle Dilemma"

According to the logic in this piece, if I sell you the Brooklyn Bridge and someone later tells you that you have to give it up, the villain is the person who told you that you did not own what you paid for. Or extending the logic, no one lost money with Bernard Madoff because they paid for it and thus own it, even if they bought a fantasy. But surely Madoff is the crook, and the real villain of the Kindle tale is not Amazon but the outfit that posted the unauthorized copies to begin with.

I would suggest they’re both villains here. If party A someone sells me the Brooklyn Bridge because party B told them they had the rights to it, and party A didn’t bother to find out if that was true, then yes, party A (Amazon in this case) is at fault as well.

Second, if these were print books, would it have been okay for Amazon to break into your house, steal back the print copy and leave the money you paid for it on your bookshelf? Why did Amazon feel the need to delete these books? I think the answer is “because they could” rather than “because they were legally required to do so”. You’ll note that Apple has pulled many Apps from their store due to rights questions, yet they have not deleted a single one from a customer’s account.

Amazon is in the wrong here for many reasons.

Which is not to say Amazon is “evil” here, just woefully unprepared for the industry they’ve entered and poorly organized as well. Great article here on the difference between selling things and licensing things, and how Amazon hasn’t prepared itself for the latter.

The issue is not whether Amazon did the right thing. They did do the right thing, according to the law. They didn’t word their terms of use properly. The issue should be whether publishers and vendors of ebook readers did the right thing when they purposely used the word “purchase” rather than “license”. While I know there is concern about pushing adoption of ebooks in the marketplace, all of this might have been avoided had someone used the legally correct term in talking to consumers. If you want to keep client relations strong in a service economy, you must keep the terms of the contract clear and straightforward. [Note: Amazon isn’t all that gifted in the environs of customer relations. They ought to have emailed customers with the whys and wherefores, not just sent out an automated refund statement.]

I am not a lawyer, but the EFF does have lawyers on their staff, and according to them, Amazon did not “do the right thing” under the law:

This is Amazon choosing its “content partners” over its customers. There is nothing about copyright law that required these deletions — if Amazon didn’t have the rights to sell the e-books in the first place, the infringement happened when the books were sold. Remote deletion doesn’t change that, and it’s not an infringement for the Kindle owner simply to read the book. Can you imagine a brick-and-mortar bookstore chasing you home, entering your house, and pulling a book from your shelf after you paid good money for it? (Nor, for that matter, does Amazon reserve any “remote deletion” right the Kindle “terms of service”.)

I’ve seen the argument made that if you buy stolen goods, those are confiscated from you, but that’s done by law enforcement agencies, not the private company that sold you the goods in the first place. Amazon is way overstepping their bounds here.

But we’re in complete agreement with Amazon mishandling things in general and apparently not having put a lot of thought into policies in advance.

I’m sorry. My statement wasn’t clear. When I said that Amazon did the right thing, I meant that they were correct in pulling the content (even if their Kindle terms of use were poorly constructed). The individual who published the title on Amazon’s platform did wrong by violating copyright in the United States and Amazon was abiding by the law in pulling it even if their terms of use (that is, the contract in place with Kindle owners) were being violated. Amazon ought to have handled the communications differently. Amazon ought to have thought to place safeguards around or otherwise monitored content being uploaded to their publishing platform. But I still think they were right to pull the content.

I still think Amazon was overstepping though. They needed to pull the content from the store. If the Orwell copyright holders demanded restitution, that should have been settled as well. But there’s no way the copies should have been taken away from the purchasers. As the EFF notes, the infringement took place when Amazon sold the copies, not when the already purchased copies are read by purchaser. There’s no legal reason Amazon needed to make them disappear. If a court or a law enforcement agency declared that this was necessary, then they would be the agents to confiscate the copies. Amazon instead jumped the gun, and took on the authority of a law enforcement agency in violation of the contract they signed with their customers.

I think it’s all evident of how poorly thought-through Amazon’s approach to selling digital content has been. There are so many glaringly obvious things they needed to prepare for, and so far, it looks like they hadn’t thought any of them would occur and are just making it up as they go. A vetting process, similar to what Apple uses for its store, would certainly be a good start.

I agree, what Amazon did was precipitous and wrong. However, they seem to agree with that assessment now, as well. Lesson learned, I hope. Having a wirelessly synced e-book = new capability. They didn’t use it well. But given the backlash and Amazon’s reliance on happy customers, I think they’ll not repeat this mistake again.

Also, customers were made “whole” again, financially. How angry would I be if I had a book on my Kindle, it disappeared, I received soon afterward an email from Amazon explaining why, and then I received a refund? Probably not all that angry. In fact, I’d be mad at the person who put it on there without owning the rights, and would probably leave Amazon off my anger target list. So I don’t think this will cause long-term customer relationship damage for Amazon. If anything, it will change policies and practices for them so they avoid repeating the errors that led up to this, and that seems to be what you think is the right outcome.

I agree that no great financial harm was done to customers here–although there are some exceptions, like the student whose notes and annotations on one of the books disappeared down the memory hole with Amazon’s deletions:

Justin Gawronski, a 17-year-old from the Detroit area, was reading “1984” on his Kindle for a summer assignment and lost all his notes and annotations when the file vanished. “They didn’t just take a book back, they stole my work,” he said.

What’s been damaged here is Amazon’s reputation–previously, they’ve been well-thought of by consumers. But with the advent of their video rental service through their Kindle venture, the poor execution of moving into digital licensing has made them look like the bad guys time and time again. The hundreds of 1 star reviews currently flooding the Kindle page on Amazon certainly won’t help sales.

More importantly, this incident has made the limitations and flaws inherent in DRM-laden e-books blatantly clear to potential customers. Amazon is doing a great job convincing people that e-books are “damaged goods”, flawed products with much lower value than traditional books due to all the restrictions. This hurts publishers in general as it’s hurting the nascent e-book market and driving down potential revenue as it is establishing e-books as low quality products that should be priced accordingly.

I guess the good news is that flagrant acts like this open the public’s eyes to the dangers of DRM and will hasten progress toward a time where DRM is not acceptable in the marketplace.

Looks like one customer in particular is a lot more angry than you, and is suing Amazon over the work he lost when they deleted material from his Kindle:

http://www.tradingmarkets.com/.site/news/Stock%20News/2452087/

whether a publisher’s change of heart is provided for in its agreement w/ amazon, or whether the publisher in question did not own the rights to the material, amazon was probably in a fairly tough position w/r/t the orwell titles. similar to the ayn rand debacle a few weeks ago, which was not picked up by the media on account of the lack of catchy irony.

but amazon should have had paid experts on hand who could have foreseen such a situation occurring, and worked out a better process for confirming that the ‘publisher’ is also the rights-holder. in any event, they had better do so now. this idea that a publisher could change its mind on the fly seems pretty questionable — like if it is in the contract, then it should come out. sure, amazon promises that it won’t remove our paid content *from our accounts* (*not* from our devices); but the fact that it can is disturbing.

happily, amazon cannot touch our actual devices at this point. so any non-drm, or free material should be safe as long as one has a backup on one’s hard drive. (for that matter purchases should be safe, too, if backed up — just don’t sync before you finish reading, or you’ll lose your place!)

interestingly, the fact that this is a problem seems to show that e-reading might finally be taking hold and becoming a force in the marketplace. note that we never heard about problems like this during the life-span of kindle 1.

in any event, it’s no accident that i’ve only purchased about 8 (cheap!) titles from amazon since i got my kindle. it will be fun to watch how the e-publishing industry shakes itself out. a nice break from the ‘disaster-porn’ shows on the discovery channel…

I wonder if the Kindle will spawn a new form of artistic medium where the hyperlink is given mass importance. I found an interesting discussion of the subject on Pandalous. It’s here: http://www.pandalous.com/topic/is_the_world_ready_for

Jeff Bezos just posted a mea culpa for this debacle, writing: “This is an apology for the way we previously handled illegally sold copies of 1984 and other novels on Kindle. Our “solution” to the problem was stupid, thoughtless, and painfully out of line with our principles. It is wholly self-inflicted, and we deserve the criticism we’ve received. We will use the scar tissue from this painful mistake to help make better decisions going forward, ones that match our mission.”

The apology can be found here:

http://bit.ly/2sHdW

Glad to see this from Bezos, and it’s rare to hear a CEO be so frank and honest about a company’s mistake. That said, I’ll be a lot more convinced that they’ve learned their lesson when we see it reflected in the Kindle’s terms of service. It’s kind of like when Bezos said that they’d be open to supporting other file formats on the Kindle. Certainly a welcome statement, but also a meaningless one without actions to back it up.

A good article here, calling for Amazon to be open and upfront about what the Kindle can and can’t do, as well as what the actual terms of sale (or rental) are:

http://www.boingboing.net/2009/07/23/jeff-bezoss-kindle-a.html

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=f11e2011-6685-4cdd-9de7-b779b4e291f2)