- Image via Wikipedia

A recent BMJ paper by Steven Greenberg entitled, “How Citation Distortions Create Unfounded Authority,” touches on a problem identified by Andy Kessler in his book, “The End of Medicine” — medicine isn’t scientific enough yet.

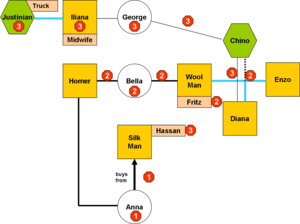

Greenberg analyzed citation patterns among papers surrounding the belief that beta-amyloid is produced by and injures skeletal muscles in Alzheimer’s patients.

What he found is that social citation dominates scholarly citation, and that citation patterns confirmed hypotheses rather than disputing them. This effect also occurred among funding requests and grants.

The most authoritative papers in the set included four papers from the same lab, two of which used the same data but didn’t cite each other. A whopping 94% of citations flowed to these four papers. Six of the 10 most authoritative papers didn’t provide primary data (five were model papers, one a review).

Six papers that were isolated from the citation map provided data that disputed the beta-amyloid belief. Only 6% of citations went to these papers.

Citation diversion — the practice of misrepresenting a citation’s meaning — occurred in three papers early on. Over 10 years, these three papers led to 7,848 supportive citation pathways. Overall, this explosion of support occurred throughout the set of papers on the topic — a seven-fold increase in supportive citations compared to almost no growth in citations to papers critical of the hypothesis. Greenberg refers to this as a “lens effect,” a magnification effect that distorts the underlying reality.

Greenberg also documents citation invention, where authors in subsequent papers make claims about beta-amyloid, cite papers, but the citations don’t point to papers that support the author’s claims.

Finally, he found the same effects at play in approved funding proposals, with citation diversion and invention used to secure grants.

Greenberg identifies four major problems streaming from social citation practices:

- the preference for positive results in the literature leads to a bias for advancing known hypotheses

- the passive-aggressive nature of academic medicine means that instead of attacking or even acknowledging critical claims, critical papers are just not cited — they’re orphaned out of politeness

- these two behaviors lead to a social citation cascade that can flood the science with a cascade of under-scrutinized confirmatory results

- funding for new research adds funders’ desires to pursue viable hypotheses, further cascading convincing theoretical narratives with apparent (albeit social) citation strength

For medicine to become scientific and not about stories, the kind of social citation captured here needs to be limited sharply. Evidence-based medicine isn’t the answer, since it’s often susceptible to the same pernicious effects, especially since it can only evaluate what’s been funded. Veering from narrative to narrative, and having these frameworks persist for years and years only to be wrong or ineffective, erodes trust in medicine and blocks advances toward scientific solutions.

Medicine is at its best when the science is simple and clear — the powers of vaccination, nutrition, infection control, antibiotics, chemotherapy, and most surgeries are beyond dispute, and lives are saved or extended daily by these interventions. But while the search for crystallized answers is underway, a system that rewards misleading, positively biased information cascades needs to be restructured to allow the science to emerge only when its ready.

This means changing the publish-or-perish mindset, putting incentives in the right spots, qualifying research outcomes more equivocally, educating authors and researchers on the perils of sloppy citation (and the lensing effects it can have), and doing a better job of detecting when citation invention or diversion is occurring.

Social network theory has a role in this. Beyond the appeal of Facebook, Twitter, and other social media tools, the effect social citation has on the expression of research, in medicine and in other fields, is another reason why publishers need to understand and learn to deploy social network solutions — to enhance collaboration, and to eliminate misleading information cascades.

Social citation is the “socialized medicine” we should be worrying about in scholarly publishing. But can it be reformed?

Discussion

10 Thoughts on "Diversion, Invention, and Socialized Medicine"

Fascinating post Kent. Many scientists are very conscious of the phenomenon, but they are unclear how the change in culture necessary to prevent this can be effected.

You suggest deploying social networks to eliminate this. But given the self-organizing nature of these and the preferential attachment (rich-get-richer) typically observed among nodes, isn’t there a danger the problem would be exacerbated? (Or do you envisage a publisher’s ‘invisible hand’ that validates, guides and prunes links?)

I haven’t entirely thought it through, but I was viewing it as a possible measurement tactic superior to raw citation counts. The methods Greenberg outlines seem scalable. Why not make a business out of it, and trump ISI? Then, we could not only have citation counts, but trace citations to key articles, evaluate those articles, and give citations a diversion, invention, or social pressure measure (basically, a BS measure). Wouldn’t it be interesting to see how much of a popular idea is BS?

The goal would thus be a more complex network in which the edges (links/citations) had values (which could even be negative I presume).

I’m struggling on the issue of scalability though. Aren’t we essentially talking about a Faculty of 1000 for links – in which human intervention is needed to assess the merits of citations? And wouldn’t this introduce subjectivity throughout?

I had the same scalability concern until I realized that, at least in this case, 90+% of citations went to four papers and that papers that disagreed jumped out in contrast. With a map generated using social media rules, you might be able to find the source of a belief system, evaluate its fundamentals, and go from there. There are plenty of people evaluating the primary literature. What if evaluating citations became part of the system in some way, tied to these surveillance publications or to blogs or DOIs? What if you could flag a citation as “correct, diversionary, or invented”? What if you could see papers that were valid but uncited? I think it could work, but it will take a finer mind than mine to see how to do it.

Hello Kent,

I really enjoyed this post. I was just talking to a manager of a small journal the other day regarding how few journals utilize a citation parser and essentially fail to check references.

I agree that the problem seems to be how a person could go about ranking the merit of a citation in the context of another article. You gave an example where the four most cited articles came to vastly different conclusions than the un-cited articles on the same topic. Although in this scenario it is easy to see the discrepancies, I’m sure that we will run into problems down the road when the differences aren’t so obvious and the line isn’t easily drawn.

I like your idea of creating some kind of program to mark citations as “correct, diversionary, or invented.” It seems to be a very close cousin of Wikipedia’s method of notifying users when information is cited and sources are listed. The question is, how could you do this across all social sites and who would do it?

I think it’s really the responsibility of authors, reviewers, and editors to check references before publishing an article. Further, I think it’s the individual consumer’s responsibility to never assume the validity of sources on non-reviewed, social forums. It calls back to the old saying “Don’t believe everything you hear on TV.”

Even as I write this I realize the ideal nature of my suggestion and how relying on individuals to do the right thing has, thus far, left us swimming in specious facts.

Fascinating read and analysis, Kent!

We seem, however, to be returning to the early 1970s where proposals for classifying the semantic intent of the citation were proposed and then abandoned in the realization of the cognitive work that would need to go into it, not to mention the fact that many citations are ambiguous, have multiple meanings and generally resist classification.

The main issue appears to be an attempt to create an empirical and quantitative system that resists subjective bias and intentional gaming.

Can this really be done? And more importantly, does it result in a better evaluative tool for scientists?

I think a difference between now and the 1970s is the social media infrastructure we now have at our fingertips. Google is basically a form of social citation writ large and aimed at Web sites. It works pretty well. Could the same thing be done for scientific citations? I know people who have taken stabs at it, but without the sort of qualitative overlay it needs to really resonate/shake things up.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=08034bf3-93b5-4bd4-b5e7-0420371ffc53)