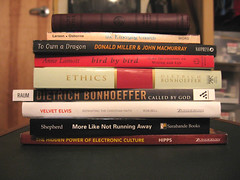

- Image by jakebouma via Flickr

Journals were among the first to feel the effects of the Internet, but now it’s the books turn. With the Kindle, the Google book settlement, e-books, print-on-demand, and self-publishing ventures, they have their hands full.

With so much going on, it only follows that irrational behavior will crop up now and again.

Take, for instance, the recent stance by two mainstream fiction publishers to delay the release of e-books for months after the release of hardcovers, despite the fact that they earn the same amount in profit for either format.

Instead of focusing on revenues, these publishers (Hatchett and Simon & Schuster) seem concerned about abdicating power to Amazon and readers, and lowering prices throughout the book system overall. And while there’s reason to take measured approaches, alienating customers and pushing books into a more marginal position in a crowded information world both seem destined to fail.

On the rational front, Springer recently announced that it will be supporting its entire list using print-on-demand in a partnership with Amazon’s CreateSpace. As a spokesman put it quite succinctly:

. . . this shift to an inventory-free distribution model using print-on-demand is the next logical step for the future of book publishing. The convenience for our customers and the obvious economic advantages made this an easy decision to make.

In the realm of increasingly social media, a flattened information space, and new publishing approaches, the best way to marginalize traditional books is to delay their release, punish fans with higher prices (despite equivalent margins), and cede territory in the digital information age. Springer’s move makes the most sense — take advantage of the improvements to manufacturing, inventory, distribution, and purchasing systems.

If you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.

Discussion

23 Thoughts on "Churn in the Book Space: Rational & Irrational Behavior Among Book Publishers"

Isn’t really the bigger issue for book publishers the economy at present? I suspect there are graver concerns over statistics that show people are buying and reading fewer books at all. Publishers should be more alarmed about that than any possible future switch to e-books, self-publishing etc.

I can fully understand why book publishers don’t want to tied to one distribution source – it’s like a journal’s publisher giving one subscription agent massively preferential commission, when they are only one route to market.

I suspect that this is part of a wider power game with Amazon, rather than just trying to ignore e-books. After all, Hachette and Random House have been fairly proactive in releasing e-books for the iPhone and at regular prices as far as I can make out – e.g. £6.99. I suspect that they just don’t want to be bullied by Amazon, and who can blame them for wanting to not bow to one intermediary?

I am not with you, Kent, on this one. I think Mark Lord gets at the issue, which does not really apply to scholarly books. The issue with selling ebooks for trade publishers is that Amazon is determined to destroy the bricks=and-mortar supply chain, for which trade (but not scholarly) publishers are highly dependent. Amazon is perhaps 10% of trade sales, perhaps 25% of scholarly sales. For the trade publishers full support of ebooks requires meaningful competition among ebook purveyors. Right now the game is heavily dominated by Amazon. This will change in the coming year, with the Android devices and the Apple Unicorn. A strategy of slowing down the ebook migration makes perfect sense for a trade publisher. Ultimately, it’s not about print vs. ebooks; it’s about monopolistic market dominance by one player, Amazon.

Yes, but look at the bricks-and-mortar world, in which Barnes & Noble controls a major slice, WalMart is coming on strong, etc. Are they slowing down “The Lost Symbol” to WalMart because it might take over the print space? Monopolistic practices don’t just occur online, and consolidation bordering (ah, remember Borders — oh, sorry, flashing forward to 2011) on monopoly already arguably exists in the retail book space.

What am I missing?

Another factor is control, on the part of the publisher. As you have so ably pointed out, Kent, it is suddenly becoming very easy for authors to publish their own books (simultaneously as eBooks and POD) and for authors of backlist books to strike their own deals for electronic distribution (e.g., Covey’s recent deal with Amazon). The manufacturing, promotion, and distribution of hardcover books–getting those big stacks of books in the front of the store at Borders–is something only the big publishers can do on any consistent basis. I think they have a big incentive to cling to that advantage. How long that will last is anybody’s guess. Coming up with a way to replace that advantage with something that works in the digital world, and which only THEY can do, is a huge challenge–in fact, it is arguable that an agile, creative, and highly motivated author can do a _better_ job of exploiting the digital environment for their particular book than a big publisher is likely to do for them. But they are going to have a very hard time getting stacks of their books on the tables and in the windows of the bookstores, and there are still people like me who actually do go to bookstores. So, if you were a big trade publisher, wouldn’t you want to cling to what makes you invaluable? I could be snarky and call this “survival of the fattest” or more charitable and point out “hey, these publishers just want to be _needed_” . . . (Full disclosure: I actually DO want the big publishers to succeed, and I do think they can add a lot of value; I’m just pointing out how important that initial release of hardcovers is to them right now.)

–Bill Kasdorf

Joe has it exactly right. I even have math to prove it. Trade publishers will have great difficulty surviving in a world dominated by a single ebook platform, and they need to keep Amazon from moving disruptively upstream in the supply chain.

So, marginalizing emerging reader preferences in a competitive information space is how publishers cling to relevancy and keep Amazon from moving upstream? While they publish less, and authors publish more themselves, and help Amazon disrupt? Hmmm, I think I sense a losing battle. As I posited, if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.

Kent, haven’t you warned publishers in the past that if they didn’t take charge of these new markets, that companies like Apple and Amazon would soon rule the roost? Isn’t this just an attempt by publishers to control their own destiny? Here’s an excellent article that better explains what’s actually happening here. This is about wresting control from Amazon.

You note that the publisher receives the same profit on an e-book as a hardcover, but that’s probably only a temporary situation. Amazon is subsidizing e-books right now, willing to sell them at a loss in order to establish the Kindle market. They pay a publishers more than the $9.99 price an e-book sells for. This is a bad deal for publishers in the long term because it 1) establishes the value for e-books at $9.99 or less in the market, and 2) once the market is established, Amazon is unlikely to keep subsidizing things.

Amazon is about a storefront. They have arguably the best storefront online. Books are a major part of their business, but publishers are used to capitulating to bricks-and-mortar sellers (i.e., selling on consignment, selling at 55% discounts). Why they think they’ll be successful defending against disruption by making life less rewarding for fans is beyond me.

I do agree that publishers need to control their own destinies. Alienating customers seems like a stubborn way to do this.

I think it’s wise to take the bull by the horns now before there’s one specific format for e-books that’s established that locks customers and publishers into one supplier and one price point. As the record companies learned, having one company putting a choke point on an entire industry (Apple in their case) is not a good thing for controlling your own business strategies. No one is intent on stopping disruption, they’re intent on stopping one company from controlling that disruption. Set up an open market that allows all companies to compete fairly and allows publishers to price their products as they see fit, and you’ll see these delays disappear.

And if that means annoying a tiny percentage of readers, that’s too bad.

But there is already, in effect, one format, in that any digital text can be easily converted into ePub, mobi, LRF, PDF, txt, and a number of other formats by engines that already permeate the e-book space. Smashwords’ “Meatgrinder” is a perfect example, and they provision e-books to B&N, Amazon, Sony, and others, in addition to selling them directly. The issue to me isn’t control of product, but engagement with audience. Readers are moving to e-books, and I’ll bet that in a year, the notion of “tiny percentage” will have evaporated. So, if I can’t get a Simon & Schuster romance or mystery or history on my e-book, but I can get a highly rated e-book from another publisher or source, who loses? Not the reader. They are programmed to not lose. They will find a way to win. The publisher can be part of this or not.

Everyone has to play with chokepoints in their value chain, whether it’s printers, buyers, delivery services, or storefronts. To pretend otherwise is unrealistic. Is Ingrams a chokepoint? The USPS? Donnelly? Mohawk Paper? B&N? Yes, all are high-volume players in a highly consolidated market. The same will happen to e-books, and prices will fall, but margins may not. Doesn’t “taking the bull by the horns” start with getting in the ring?

How many of those formats work on a Kindle? How many devices support the Kindle books I buy from Amazon? Monopolies are bad for consumers and bad for producers. The difference between the Kindle and the other companies you mention is that while they are large players, their systems don’t cause lock-in resulting in them being the only player.

Do you think the e-book market will double or even triple next year? If so, that’s still fewer than 10% of book sales, and the Kindle controls less than half of that worldwide, so the percentages are still small. Now is the time to risk offending, rather than waiting until you’re annoying 50% of your customers.

Monopolies are bad for consumers, but consolidated industries are normal and usually a sign of efficiency. My point is that it seems panicky to project a monopoly where there will likely only be consolidation. Kindle has a defense built in for publishers, as you note, so they should be even less panicky. There is no “lock in” with a Kindle, in the sense that I can buy a Rex, Sony, Nook, or (soon) PlasticLogic, or use my iPhone, for e-reading. If the e-book market behaves like a hot-adoption market, the multiplier could be more like 50x. Amazon recently stated that for books that have print and e-book versions, they sell 48 e-books for every 100 print books. That’s more than a marginal percentage. Did One-Click create a monopoly around book buying? No, but it helped create a market leader that the book industry probably has celebrated for its efficiency in selling Harry Potter, Dan Brown, and others. I just don’t think a storefront, even on an e-reader, is all that scary.

There’s a big difference between consolidation and monopoly. It’s possible to consolidate around a format but not leave the market reliant on only one device and one storefront. That’s Amazon’s goal here, and working to prevent it is a smart move. This is a nascent market and sitting around letting someone else decide your fate doesn’t strike me as the way to go. Publishers still have the power in this relationship.

If you buy a Rex, or whatever, can you read your Kindle purchases on that new device? If not, then you’ve created a huge barrier to customer freedom, resulting in a monopoly lock-in.

Do you really see e-book sales increasing from less than 3% of the market to the majority of the market within one year? That’s a little wildly optimistic.

Bezos’ numbers are cherry-picked and essentially meaningless, as I pointed out at length here. I’ll reiterate:

To counter some of your anecdotal evidence, we (CSHL Press) have 6 books available through the Kindle store. We’ve sold only a few Kindle copies of each this year, while the print copies of those same books continue to sell very well. The ratio is closer to one to hundreds than Bezos’ alleged 1 to 2 sales rate. And I’m glad you brought that number up because it’s a good example of Amazon’s cherrypicking and misleading use of statistics. What does that mean, “for books available in e-book and print formats, Amazon sells 48 e-books for every 100 print”? Take a look at Kindle’s current bestsellers (not sure if these have changed since I first wrote this response a few days ago). 9 of the top 10 are available for free, and 8 of those books are available in print as well. How does that skew Bezos’ numbers? Amazon has 350,000 plus books in its Kindle store. An impressive number until you realize that nearly 300,000 books were published in the US alone last year, with worldwide estimates being closer to 2.55 million (pdf link). The entire Kindle library represents only a tiny fraction of the total number of books available, so can we really generalize much about the vague sales figures offered? Another classic bit of spin was the claim that the Kindle outsells every other product on Amazon, which was dissected here. Bezos’ and Amazon’s statements must be taken purely as marketing copy, at least until they want to establish some actual credibility by releasing numbers.

Kent, if publishers followed your direction, the Kindle would emerge as the Windows of ebooks. Think about that for a second. This is not a matter of formats but of proprietary standards.

Springer’s action may have been inevitable, but it’s a disappointment for those of us who care about quality printing. I taught an advanced probability course using a Springer text this past semester, and the difference in quality between the regular version and the print-on-demand version was like night and day. I pity the students who had to use the latter. Even those students who printed out the PDFs from Springerlink on their personal $100 printers had it better. And this difference in quality is not a one-time anomaly and not restricted to Springer. I’ve seen the difference in head-to-head comparisons in dozens of cases. The publishing executives who claim the difference nowadays is negligible must have very poor eyesight.

If this were really about limiting Amazon’s current or future control of the market, Simon and Schuster would delay release of ebooks for Amazon but release them at the same time as hardback for other providers.

May I raise my hand again to state what I think is the obvious? This discussion has centered on whether publishers are trying to prevent Amazon from having a monopoly, and whether they’re sticking their heads in the sand (or elsewhere . . .) about where the book industry is going, and whether Amazon is undermining the pricing model — and all of these are important issues. But let’s step back and look at the original issue of publishers _delaying_ the e-books until after the hardcovers have been out for a while. I really think that from the publisher’s point of view this is very little different from the common practice of delaying the paperback until the hardcovers have been out there a while. Was that because they were insensitive to their customers’ desire to buy the paperbacks? Heck no, they were trying to optimize their revenue! Fundamentally, that’s what holding back the e-books is about. It’s not a religious issue. As I mentioned in my earlier comment, the ability to get those stacks of hardcovers out there is currently a distinct advantage the big trade publishers have and they are going to exploit that advantage as long as they can.

–Bill Kasdorf

And I forgot to add: what will change their behavior is the economics, when getting the eBooks out there right away DOES optimize their revenue.

I also want to point out that people continue to talk about “books” as if they’re all the same dynamic. The situation for trade publishers is quite different from that of scholarly publishers. I think that for scholarly publishers, eBook + POD is inevitably the way to optimize income and minimize cost (and investment). Not the same, at the present time, for the big trade publishers.–Bill Kasdorf

I completely agree that now is the time to take on Amazon and ensure that they are not able to create a monopoly storefront for ebooks.

However, the actions taken by Hatchett and Simon & Schuster do nothing to further this aim. If the aim is to create a heterogeneous ebook ecosystem resistant to monopoly control, then publishers must reward those companies that employ technologies and practices that will lead to that outcome.

As Dan points out above, publishers might do this by releasing ebooks only in ePub format to coincide with the launch of the hardcover edition. If Amazon doesn’t wish to support ePub, so be it. Let them wait (in fact, let them wait even longer than 3 months). This will provide a boost to storefronts and devices that employ open standards, allowing them to become competitive enough to challenge the Kindle’s current lead and force Amazon to support the ePub format, thereby reducing Amazon’s ability to create a monopoly.

Simply delaying release of ALL ebook formats does not penalize Amazon in any way relative to other ebook purveyors and thus will not hinder Amazon’s monopolistic goals. In this I agree with Kent–their behavior is indeed irrational and accomplishes nothing beyond frustrating readers of all ebook devices.

This would be something like the music companies making DRM-free files available to many stores like Amazon’s but not to iTunes, which helped them in their negotiations to get variable pricing from Apple.

That is a good example, yes. Though in this case, publishers would not so much be directing their ebook release policies explicitly at Amazon so much as setting some ground rules for the industry. If ebook purveyors–including Amazon–want to sell ebook editions of new titles at the same as hardcover, they would need to play by the rules and use open formats. Amazon, just like everyone else, would be able sell ebooks of current hardcover titles so long as they agree to sell in ePub format.

This would be transparent and fair to all storefronts and device makers, would be good for publishers (who would be able to maintain price controls), and it would be good for readers as they would be able to choose their preferred edition, storefront, and device. Moreover, such a groundrule would make it difficult for anyone to form a monopoly.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=4d3c55c1-c198-404b-b714-5dbf1f48ec60)