- Image via CrunchBase

The emerging “me at the center” customer expectation is a compelling consequence of the digital, mobile age. Maps re-orient themselves to where you are instead of you having to find H-3 or some other grid quadrant. Content follows you and stays in sync with you. Your phone number is permanent and provides connections for voice and texting. Your DVR can be scheduled and managed remotely.

Technology companies are racing to cement “me at the middle” as a reality, making things easier for consumers, anticipating an irresistible trend. Meanwhile, publishers — concerned with optimizing their systems for production rather than for consumption, worried about reining in costs to preserve comfortable cultures, and catering to authors with projections of prestige — remain “we at the center.”

Amazon’s Kindle platform is perhaps the best case of a modern technological publisher putting me at the center. Yes, the Kindle is a device (and, yes, lending is coming), but the Kindle’s most important aspect will most likely end up being its platform — which integrates the device thanks to its ingenious connectivity. The Kindle device can be constantly connected, so that the platform is aware of what point you are at while reading items on the device. Access the same text later on a different device, and you’re put at the place you stopped, thanks to a platform that synchronizes things for you. It puts you at the center. You don’t have to do anything.

Netflix is moving in the same direction. One of the most interesting things I discovered using my new Apple TV came about when I was waiting for the Apple TV unit to arrive. To warm myself up, I tried streaming some TV shows from Netflix on my computer. It was fun enough, but I stopped one half-way through one, deciding at that moment to wait for the device. When my Apple TV unit arrived, I plugged it in, accessed Netflix — and was told what I’d just watched and asked if I wanted to start watching it where I’d left off.

This was a device I hadn’t owned when I’d watched the show, but the Netflix platform put me at the center. It felt a little magical, I have to admit.

Pandora is also pursuing a “me at the center” strategy by making its player compatible with every possible device there is, from Blu-Ray players to gaming systems to car stereos. Google’s attempts at this so far (e.g., Wave) have not really panned out, but you can feel them stitching things together to meet this expectation. And Apple has Mobile Me, their platform for synchronized files and access.

Yet we traditional publishers continue to rebuild our Web sites, dangle uncoordinated apps and syndications in front of our users, and allow intermediaries to separate us from our true audiences (i.e., institutions, aggregators, and tertiary storefronts).

The general culture of publishing has problems when facing a challenge like this. We’re still about serial publication, inherently author-focused, and somewhat comfortable in our cultures. As David Worlock writes in an excellent post about the forthcoming book “Creative Destruction“:

. . . real world companies receiving the painful jolt of a swift kick in the digitals can and must re-invent themselves through a three stage process of re-generation. This involves a transformation of their core business, the discovery of big adjacencies, and the ability to “innovate ’round the edges.”

We could use a kick in the pants. We’re being surrounded by players who are poised to dominate our commercial futures, and we’re not positioned to compete well. Customers don’t care who provides them with the best experience, price, and variety. They will take what they can get. If we think the prestige of our brands or the power of our ingrained traditions will hold this at bay for long, history isn’t on our side. But again and again, we seem to think that digital = new. It doesn’t. Digital (gaming, music, publishing, telephony) is more than 30 years old, deeply entrenched, and it isn’t going away. In many companies, digital is still viewed as “experiments” instead of core; performance is measured in months instead of years; commitment is brief and furtive instead of firm and absolute. Worlock nails it when he writes:

By far the larger part of the management of consumer book publishing known to me have, while embracing a digital strategy, regarded everything that emerges from it as a defence mechanism to protect the printed book. . . . Managements seem to view continuity as a strategic aim, and re-invention as a car crash unless it has instant acceptability.

We’re still filled to the brim with people who can run the familiar terrain of periodical publishing, our cultures quietly reinforced through daily action and practice even if there is a clarion call from the customer for change. We have a skills gap we can hardly detect because we have plenty of skills but can’t see or deal with the fact that they’re incomplete and just slightly wrong. From top to bottom, our organizations need to be retooled, especially philosophically, as Worlock writes:

The problem we all face is not just that it is very hard to get people who are not used to it to start analysing the active, problem solving applications of content in the lives of their users/consumers, but it is well nigh impossible to do that if the end purpose is to defend the rigid linear internal production workflow model of the publisher, who cannot conceive of relinquishing his containers or his pricing models, or the accident-waiting- to-happen business model of advertising.

It’s tempting to think these changes will only be reflected in our digital divisions or offerings, but the fact is that we have to change fundamentally — our digital strategies are too often predicated on broadcasting from the big Web site; our cultures are often defensive, entropic, and arrogant; and our business goals stream from complacency and caution.

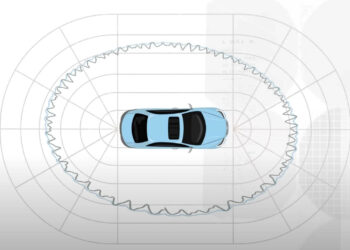

As Jack Welch famously said, “When the rate of change outside exceeds the rate of change inside, the end is in sight.” For publishers, the problem is that the customer is essentially being pulled away from you, moving into a world in which each of them is at the center of an information sphere filled with interesting material, sufficient serendipity, and trusted filtering — the likes of which traditional publishers can’t provide by persisting in familiar habits.

Publishers continue to conceptualize the world as “we at the center,” and it has the tinge of the royal “we” to it. The fact is that customers — in a world of abundant information, seamless technology appliances, and radically different business models — see a world with each of them at the center. Whether we’re part of that or not — well, it really doesn’t matter to any of them.

Discussion

27 Thoughts on "Why the Simple “Me” Beats the Royal “We”"

Great concept but you may be beating up the wrong people. What we need is something like a personal Google Scholar, that knows what I am working on and finds stuff related to that. But this is not something publishers can do, it is universal aggregation.

Primitive versions exist already. I don’t read any particular newspaper. Rather I use Yahoo! “complete coverage” pages to find articles. One interesting feature is that I can quickly compare coverage by several newspapers.

Why can’t purveyors of content (aka, publishers) can’t do what other purveyors of content (aka, Amazon, Google, Apple) are doing? There seems to be more than enough at stake, the technologies seem fairly addressable, and so forth. “Primitive versions” aren’t enough when Twitter and Facebook and Kindle provide me with sophisticated substitutes.

In the comment above, David hits the nail on the head. You’re talking about two different types of businesses, content producers and content retailers. To be an effective retailer like Amazon, Apple or Netflix, you must operate on a level above brands, an open level where you’re selling the products from a wide variety of content producers. Readers are not interested in buying material from strictly one publisher, one journal, one imprint. Someone like MacMillan can’t suddenly outduel Amazon in the eBook market simply because MacMillan only controls MacMillan’s content, where Amazon has access to everyone’s.

If you want to compete on that level, then you’re entering into a new business, which is fine, but it’s pretty unlikely that a small society publisher is suddenly going to be able to challenge technology and retail giants. Twitter, Facebook and Kindle have different expertise than publishing houses. Would it be reasonable to ask a society publisher to suddenly become a restaurateur and outdo Mario Batali? Then why is it reasonable to ask them to suddenly become another different type of business and expect them to succeed where so many (with so much more expertise) have already failed?

If you really want to put control of the market back in the hands of publisher, then perhaps a coalition, something along the lines of what Brewster Kahle is proposing, is the way to go. We’re seeing similar efforts from the television networks, building their own systems like Hulu rather than relying on tech giants like Google. It’s interesting to see that the usual New Media D’bags are jumping all over the networks for this decision (and that article is a perfect example of what’s wrong with such punditry, making a strawman argument, declaring it wrong then offering no actual real world solutions).

Seems we’re damned if we do, damned if we don’t.

One other point: what’s wrong with optimizing systems for production, reining in costs and offering authors prestige? Shouldn’t we be maximizing our efforts in all areas, rather than dumping what’s still (at least for now) a viable revenue stream? How is streamlining the production process in conflict with looking toward the future? Do you really think any publishers are sticking their heads in the sand and ignoring these sorts of developments, relying on a strategy of wishing they’ll go away? Is that an accurate picture of the industry, or just a stereotype that leads to an easy counter-argument?

When you go shopping for platforms, systems, vendors, what are your criteria? Lower costs, smoother traditional production paths? Then you’re buying a system of old. Yes, small publishers can’t scale these systems, but they can shop smarter. And I disagree with the notion that a publisher is not an information retailer (and especially react to the notion that they’re an information producer — authors are information producers, not publishers). Scholarly publishers have grown lazy in retailing their information, I’ll contend for the sake of provoking a second thought. We put out the same containers to the same audience in the same manner as ever. Meanwhile, new authors, information vendors, and formats are emerging all around us. We’re not being creative, not investing, not learning the ropes.

If we’re damned if we do, damned if we don’t, then I say we “do.”

I do think many publishers are lost, ignoring trends, feeling adrift. Centering on the user is a great way to regain perspective.

I don’t think any publishers are looking to invest heavily in traditional paths at this point. What they’re looking to do is maximize the revenue that still exists in those traditional paths. Very few, if any, journals see much of a future for print. But right now, there are still advertising dollars to be made, so print has to remain a priority. Why throw away money that’s available now even if it may not be available a few years down the line?

You’re right that “retailer” and “producer” are poor word choices. A better set is “aggregator” versus a “primary source” (though I disagree that publishers aren’t “information producers”–though we may not be information originators, we are certainly a part of that chain and produce information that is very different from what an originator would do on his own). Mark Cuban has been writing some interesting pieces about Google TV and the big networks (caveat, he’s an investor in television, so has a bias that way). This one in particular is relevant here:

…there are those that believe that any business that is doing business like they always have will inevitably be disrupted by the internet. Change or die. Right ?

Wrong

…My Rule Of Thumb for disruption in the digital world:

Aggregators disrupt ala carte . Aggregators don’t disrupt Aggregators, they compete with them.

That’s the issue we’re dealing with here, primary sources who, by their very nature, must sell ala carte versus aggregators. That’s the key question here, can we continue to coexist with these new types of aggregators? We seem to have done okay with the Barnes and Nobles and the Baker and Taylors of the world. What’s different here and why is it so threatening?

I don’t think publishers are lost or are ignoring trends. Every publisher I meet is deeply interested in new media, new business models, new revenue streams and they are following developments closely. They are, however, being cautious. It’s really easy to spend a huge amount of money on something that seems trendy now but will disappear overnight. How much effort should we have put into our Myspace pages as distribution points? How’s that Push Media system we were promised was the future a little while back? How are all those “Facebook for Scientists” investments paying off? There is no obvious path here, but in order to experiment in a big easily-seen way, you have to be willing to lose a lot of money. Given the low margins most publishers see, that’s not a viable path for all but the larger conglomerates. That’s likely why you see a company like Google being so willing to throw money seemingly randomly at anything that strikes their fancy. They can afford the losses. A small not-for-profit publisher can not.

I don’t think we’re damned if we do or don’t–that was meant to point out that if you listen to every piece of advice out there, you’re going to hear completely contradictory things. I do think you’re right in that it’s better for our industry if we control our own destiny, rather than placing it in the hands of Amazon and their like. But I think that’s more likely to happen through collaboration and coalition building, publishers coming together to create our own Hulu rather than selling out to Google TV.

I think awareness among publishers varies, and the willingness to be audacious is rare. Caution is a problem, actually. It’s predictive of being disrupted in an environment like this. You have to be willing to invest a lot of money to create a future that’s not obvious — to portray it as “losing” money is just another sign of caution and vulnerability. B&T and B&N were fine in a scarcity economy, but what about now? The expectations are completely different, so the comparison doesn’t work.

Investing in a future vision and following trends aggressively require spending money. Spending money is not the same as “losing” money. People made fun of Amazon in the early days — when will it ever make money? Google, the same. Now, both are multi-billion-dollar behemoths. Twitter has been ridiculed, but is poised to start raking it in. WordPress is making money, but had to invest millions at the start. What they did was investing, not losing, money.

Cuban’s rule of thumb is useful, but why are publishers stuck in their role? We may be able to talk the talk, but are we willing to walk the walk? Just being interested and curious and experimental can be merely “fad surfing in the boardroom” — few publishers are making sufficient investments to create a future that will resonate with emerging customer expectations, in my opinion. And as far as sizable and well-funded coalitions aimed at solving customer problems go, there’s little meaningful activity I know of. If I’ve missed something in that regard, please shed some light.

Let’s see, you mentioned 4 companies that made it. 4 out of, how many? How many Amazon or Google competitors have fallen by the wayside? How many billions of dollars in venture capital did they burn through? Did AltaVista “lose” money or was that an “investment”? What about InfoSeek, HotBot, Lycos, Ask Jeeves, LookSmart, GoTo, Overture, AllTheWeb, Teoma, Snap or Wisenut?

How many university publishers have those sorts of spare funds to gamble on being one of the 4 out of thousands to pull it off? This is an argument you and I have had before. If you’re Microsoft or Google, you can afford to be wasteful and profligate in your experimentation. Perhaps this is true for the JBJS as well (and if so, are you hiring?). Fail 1,000 times for each one mild success, what’s $10 or $20 billion down the drain? If you’re the publishing wing of an institution that’s on hard times, can you afford to gamble those billions? Is there going to be a first-mover advantage that will be impossible to overcome if you let others take the risk? Even if you can predict the right path, is it something your company can afford to build and do you have the expertise necessary to build it?

I’m with you on the disappointment in seeing publishers failing to band together. Perhaps we’re so used to competing that it’s hard to see our commonality here. Operating individually, we can’t hope to build our own Amazon. But there’s power in the group and costs can be amortized more easily when they’re shared.

Yes, we see things in a fundamentally different way when it comes to risk. You see risk in action, I see it in caution, to speak far too generally about it. However, let’s talk about some specifics. Many of the search companies you cited are still around in some form. AskJeeves is Ask.com and was valued at $1.85 billion when it was taken private in 2005. Teoma was acquired by Ask.com in 2001. AltaVista went to Overture which went to Yahoo! So, there was a lot of consolidation in a tech-heavy space. Lycos’ history is full of spin-offs and such, and it has created a lot of wealth over the years for people.

How many universities have large endowments or investment banks that they could pull from to fund ventures? Plenty of them. Why aren’t publishers positioned to help them spend that money? Good question. Why did HighWire Press emerge from the library? Because there was entrepreneurial spirit there. Why couldn’t a university press create a case for making a technology/content play compelling enough to get funded?

I just heard today of another major university library closing. University presses are folding. Is that because they experimented, tried audacious things? Or because they were cautious?

I don’t want to come off as a Nervous Nellie here–we’ve been busting our tails to bring our products into a more future-ready form and are rapidly adapting our business models, radically revamping our production process and cutting the fat of product types that are past their time. I just think the scale at which you’re suggesting experimentation is unrealistic and beyond the competency of most publishing houses. Stanford could make Highwire because of extensive technological prowess and personnel in-house. Where will the Lepidopterist’s Society find such personnel, and how will they pay them?

Break the mold, venture boldly, but do so with great forethought, with actual business plans rather than experimentation solely for the sake of experimentation. I think there’s more experimentation going on than is obvious. But it’s more subtle than declaring yourself in direct competition with Google.

For what it’s worth, Rice University Press recently closed down despite a bold experiment in going all-digital. Like sitting on one’s thumbs, being audacious does not automatically guarantee success.

For a library, “going all-digital” is usually the music to which the end credits roll.

As for scale, I think smarter buying and different vendors can help the Lepidopterists. The “build or buy” decision still matters, but knowing what you’re looking for matters more.

That was Rice University PRESS, not their library, which, as far as I know, is still kicking.

Agreed on the rest though.

“something like a personal Google Scholar, that knows what I am working on and finds stuff related to that”

To me, this is the core problem that Mendeley is trying to solve. It’s a me-centered approach to discovering the literature that’s relevant to me, right now.

I think one needs to distinguish various types of customer. One major problem with academic publishing lies in the reluctance of scholars to change their tried and true ways. Witness the drag that the promotion-and-tenure system has long exercised on advances in digital scholarly publishing. Or the reluctance of many mainstream scholarly journals to review enhanced digital books of the kind that came from the Gutenberg-e Project. Or the inertia among faculty in submitting articles to institutional IRs unless a mandate is in place. What you write about here seems to me to apply much more to readers outside academe than inside.

Academics aren’t stuck in academe all day long. They use iPads, iPhones, Kindles, and Netflix. Their expectations are being affected as well. What I wrote about here does apply to academics when they’re outside the academy, but we used to say similar things about online journals — the library will never lose centrality, old habits die hard, print is too portable and useful and “real” to be abandoned. But as libraries close or reduce their footprints, I guess we know how long we last playing defense against the sea.

Getting back to an earlier point though Kent, I’d love to hear more about why you think licensing content to aggregators is so much more dangerous in an age of abundance versus doing so in an age of scarcity. In a comment above, you said, “The expectations are completely different, so the comparison doesn’t work.” Can you elaborate?

Because their reach is instantaneously huge and the aggregation much cheaper on a per-person basis. B&T and B&N had to work physical distribution channels and carry the costs of consignment books. Containers were defined and hard to intermix meaningfully. Whatever competition went undetected in the B&T and B&N world hits more broadly and more quickly now. And many aggregators are making significant technology strides while publishers aren’t in any impactful way.

University presses have traditionally been underfunded by their universities, so have had little capital to invest in experimentation. That’s one reason STM publishing was lost to enterprising commercial publishers after WW II. Nevertheless, there have been a number of interesting experiments over the years, such as National Academies Press “open access” publishing, Princeton’s various experiments with enhanced digital books, UC Press’s multiple cooperative ventures with the California Digital Library, Johns Hopkins’s Project Muse, the ACLS Humanities E-Book Project, the AAUP Online catalogue (whihc preceded Google), etc. Universities are generally reluctant to put more money into their presses, though, because they are not potential profit centers, as their patent offices are (or big-time athletics!), and the “free rider” problem arises also since no one university really needs its own press for its faculty to be able to publish.

Sandy I think that’s an important piece of perspective. Where I work, we make a profit each year, which the institution appreciates, but the reality of it is that we contribute only a small percentage of the institution’s yearly operating budget. We are small potatoes compared to grant funding, donations, technology transfer. As such, our pool for investment comes from our own revenue, not the institution’s.

Asking them to hold off on that new building full of labs trying to cure cancer in order to fund our bid to become the new Amazon would be a tough sell. The labs are more likely to bring in money (lower risk), and they fulfill the mission of the institution, which is scientific research, not online retailing.

Ah, but will you be ready when “publishing” means “putting each user at the center of a seamless information experience”? That’s the question. And if you can’t remain an effective publisher, your researchers will move to other platforms to disseminate their works. Might be time to get some attention.

That may well be true, Kent, but just try convincing any university that investing more in its press is a good investment these days. The trend is rather to cut back on operating subsidies, or even to close presses down (as at Eastern Washington, Rice, etc.). And, David, there are very few presses that ever have operating surpluses; you can probably count them on the fingers of one hand. And among the few that do, Chicago is obliged to pay back a portion of its surplus every year to the university, not to use it for investing in new opportunities for change.

Had universities decided to invest in their presses more in the wake of WWII, the STM crisis would probably never have arisen, and there would be no call for OA.