- Image via Wikipedia

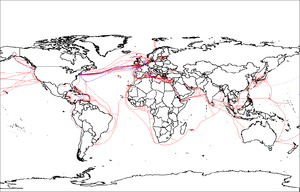

The global implications of the Internet have (by Internet standards) been long understood — mount a Web site, and users, perhaps even customers, can come to it from anyplace in the world, barring connection problems and political interference.

For the book business, though, this point has been stronger in theory than in practice, as the relatively high cost of international shipping often seems too much to bear when measured against the relatively low cost of most books. With e-books, however, the balance shifts, as a downloaded book can be delivered anywhere for the cost of bandwidth. The economics of the Internet lead to porous national boundaries. Over time this will restructure the industry, leading to the emergence of the “One World Publisher,” one of the many unintended consequences technology is always happy to provide.

The globalizing aspect of the Internet for book publishing has prompted much interesting discussion. A recent lively thread on the liblicense mailgroup, led by the always-eloquent Toby Green, publishing director for OECD, touched on the inevitability of one-world pricing, as residents in a country where prices are high will quickly find e-books in territories where prices are lower. In the consumer market, the cries have become quite shrill, often cloaked in a manifesto for “users’ rights” (how dare a publisher deny me the right to purchase a book in digital form by invoking territorial restrictions). Take a look at the site put up by Jane Litte, where readers are invited to submit their own brief accounts of how territorial restrictions prevented them from purchasing an ebook. (You can get a flavor for much of this debate at Mike Shatzkin’s blog.)

It’s easy to imagine some publishers looking at Litte’s site and shuddering — and others cheering, since exposing this anecdotal sales data is likely to accelerate the process by which all rights to a book are vested with a single publisher. One book, one publisher, one Web site, one world market. Interestingly, Random House has an imprint called One World, but its thesis is backward; its emphasis, admirably, is on multiculturalism, but a global market is monocultural. The STM journals publishers reading this blog, who come from all corners of the planet, don’t have to be told about monoculture, as they have been working primarily in English for years.

The differences between those who advocate and those who oppose One World Publishing are both cultural and economic. On the cultural side, we can identify those people who step into an enormous store even in the bricks-and-mortar world — a Wal-Mart, say, or a cavernous Office Max — and see progress: scale, efficiency, a broad display of merchandise. Others see the end of the era of the hand-crafted. They point to the vacant storefronts on Main Street and the inability to find someone who will press your shirts in just the right way. The book publishing world of today thus gives us a new reason to debate the Big and the Little. Big is global, Little is local. Big is going to win; my head tells me so; but my heart urges me to write a paean to the Little.

How did this tension between the global and the local come about? Some background is in order. Print books, for all their many virtues, inherently pose large problems for their distribution. Books must be warehoused and shipped; demand must be carefully estimated in advance (the hardest trick in the book business); shipments of titles must be coordinated with publicity efforts; a network of sellers and resellers (the supply chain) must be assembled and made to work in coordination. Getting these things wrong can destroy a publishing company; a company that gets these things right prospers and often ends up acquiring those rivals with less efficient supply-chain operations.

Because of the difficulties of physical book distribution, most publishing throughout the 20th century was national. A book was published first in, say, London for the UK book market, and then trading partners were found to take on the distribution of the title in the U.S., Australia, etc. Although somewhat attenuated, this practice continues today. A well-known example in the popular book market is that of the Harry Potter series, which was published in the UK by Bloomsbury and in the U.S. by Scholastic. This resulted in one of those oddities of the print book world: one book with two different titles: in the UK, “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone”; in the U.S., “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.” Now what, you may ask, is a “sorcerer’s stone”? An invention of marketing for a local customer base, as magical as anything that takes place in the novel. For scholarly books, it was not uncommon to have books published in “co-editions,” with different partners taking on the responsiblity of book distribution in their respective local markets.

On the other hand, the new use-cases for ebook distribution are clear. Seated in a cafe in Venice, a patron downloads a novel published in Australia to a mobile phone; disturbed by the high prices of books in London, a prospective book buyer walks right by Foyle’s and purchases an e-book from an American vendor. The Internet knows no boundaries, and attempts to put up barriers to the transmission of digital content are always subject to the ingenuity of a pimply teenager, who has put aside his schoolwork in order to focus on his true mission of sticking it to the Man. It may or may not be true that information wants to be free, but it is certainly the case that it wants to be global, to boldly go where none before the Internet have gone.

Thus with e-books, a territorial tension arises. The Internet and e-books press for a single, global market, but print books are largely distributed nationally. If there is to be a single, global publisher of the digital version of a title, must the print world, which is still far and away the largest part of the book business, align itself with the new structure for digital books? Or should the worlds of e-books and print operate separately: a global publisher for the e-book, a collection of local publishers for print? Local publishers will howl at these suggestions, of course, as their future is largely dependent on their ability to leverage their current position in print to digital publishing.

It would be hard to find someone to say that e-books will not continue to increase their market share, though many people in the industry want e-books simply to fit into the existing supply-chain — that is, they welcome the Internet and e-books, but do not accept their disruptive nature. That is a very big mistake. While an e-book can be a substitute for a print book, e-book publishing cannot and will not merely substitute for print publishing. Many librarians are also making this mistake, insisting on purchasing e-books in the same way and from the same vendors that traditionally (and effectively) sold them print. At best that is a holding action.

The digerati will win this one; it is only a matter of time. But there will be unintended consequences, as there always are. Publishers with clout will demand global e-book rights; over time, the practice will become increasingly widespread and then universal. It is probable that print rights will get caught up in these negotiations, as publishers are finding ways to market print and digital texts in tandem.

The question is, which publisher gets the rights? Here the network effects of the Internet kick in. If an author or agent faced with multiple options must determine which publisher to work with, and the author realizes that there will be only one publisher, whose task it will be to serve a global market, then the choice will be to sign with the publisher best equipped to reach the widest market. If the print rights are part of the bargain, as they almost certainly will be, then the advantage goes to the publisher with the strongest print market. A few quick calculations leads the author to conclude that the best publisher — the single publisher for that book throughout the world — will be American or an international publisher such as Oxford University Press with a deep engagement with the Americn marketplace, as the U.S. book market is the world’s largest by far. Globalization and e-books thus extends the reach of all publishers, but not equally. The Internet is not a democracy.

Publishers that serve smaller markets, publishers working in Australia, India, even in the UK, increasingly will find themselves uncompetitive as the national trading barriers come down. This in turn will accelerate the acquisition of smaller publishers based outside the U.S.; those smaller publishers will become editorial units (one might say “be reduced to editorial units”) feeding locally-created products into the international digital publishing machine. Wal-Mart trounces Main Street.

Trans-lingual publishing may participate in this trend as well, though not necessarily at the same speed. Consider this: Is an author working in French likely to sign with an American publisher working in English in order to place the rights to her book in the largest market? In trade publishing, where successful books are often published in many languages, we have already seen some consolidation that cuts across languages as well as national boundaries. In scholarly publishing, on the other hand, this trend may move more slowly, as the small market for such books works against the need for translations. In any event, scholars can read multiple languages, in effect providing a capability for themselves that publishers provide as a service in the non-scholarly market.

Developing a publishing strategy is like a chess match, where the winner is the one who can accurately forecast several moves ahead. When the idea of e-books was first bruited about, most of the discussion was on the savings in paper and transportation costs. But e-books will mean far more than that. Once the chain reaction begins, we have to brace ourselves for the explosion.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "One World Publishing, Brought to You by the Internet"

Do you think it might be possible that the disruptive nature of ebooks will cause the book publishing industry will go the same way as the music publishing industry?

Most ebook readers will run on Linux, meaning it is entirely possible to expose a root shell from which the reader could be disassociated with any user account. Not to mention there are a plethora of pimply teenagers with perl scripts to convert almost anything to a pdf these days.

It certainly wouldn’t be very difficult to start converting bought books to pdf and share them over the internet. The practice already happens quite extensively with certain college textbooks.

In the case of commercial fiction, I find it hard to see what small markets (e.g. Australia) have to lose by gaining a global market without printing and shipping costs. When I learn about a Aussie book I want to read, it’s frustrating to have to purchase it and get it shipped from Australia and chances are I’ll read something else instead, but with e-books – instant gratification. Marketing is tough in a Wal-Mart world, but a mid-list title could sell a lot more copies if the territorial barriers come down. Word of mouth among readers is without borders.

The print/digital divide isn’t quite as sharp as Joe depicts it here. Some years ago Penn State Press stopped using a UK-based distributor in favor of making its books available in the UK market through Lighting Source UK. With Amazon’s BookSurge (or whatever it’s called now) having POD facilities distributed around the world, the cost of distributing print has come way down; print books are now manufactured locally. The CCC also is using a network of printers worldwide to supply print articles to customers who get their permissions through the CCC and want hard copy. The Espresso machine is being bought by libraries. Eventually, as librarian Rick Anderson predicted at the Charleston conference earlier this month, we’ll have the desktop equivalent of the Espresso.