Over the past few years, I’ve been privileged to attend a dozen or more editorial summits for many different publications in a variety of disciplines — animal, vegetable, and mineral. I’ve been asked on most occasions to talk about new publishing technologies. Each event has had at least one thing in common — one or more vociferous journal or book editors who think blogs are beneath contempt. Judging from their comments and criticisms, blog content is questionable, blog authors are indulging in mental onanism, and the genre itself is marginal at best.

It’s clear at these meetings that this vocal group is not the majority. Many editors are interested, curious, and open. Even at that, since I work hard at this blog, it still makes me a little defensive.

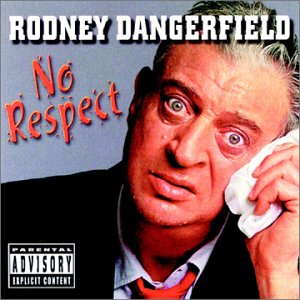

Like Rodney Dangerfield, it sometimes seems that blogs get no respect.

More than one Scholarly Kitchen blogger has had ideas lifted from the blog and reused in more traditional scholarly communications without citation or acknowledgment. If these ideas had been printed, I think that wouldn’t have occurred. Ironically, most blogs are deadly diligent about citing their sources because the technology for citation — i.e., linking — is built in, and the editorial expectation around blogs is that if you are able to point to something, you’d better do it, or a comment will quickly bring you down to Earth with a link, hot as a smoking gun.

Luckily, I’m able to respond to the doubters with a list of achievements any editor of any publication, traditional or non-traditional, would likely be proud of — the Scholarly Kitchen unearthed a scandal serious enough to force an editor to resign; we’ve been nominated for a prestigious award and beat some very strong competition; our reputation for “telling it like it is” has people correcting their behavior themselves with just an inquiry from us; we’ve garnered high-impact essays at the expense of other outlets; our contributors and commentators are in a class by themselves; and so much more.

At the same time, blogging itself has matured throughout the publishing world to become a huge part of editorial activities at all levels, from the New York Times to the Wall Street Journal to the Atlantic. Independent blogs and blog networks like TMZ and Gawker and Mashable and ScienceBlogs have risen to prominence, broken news, endured scandals, changed editors, redesigned, expanded, and so forth — you know, all those things traditional publications do. Blog news platforms like the Huffington Post and the Daily Beast are ascending while traditional news outlets struggle.

Maybe it’s the lousy comments on blogs that make them so suspect? Unless it’s a poorly moderated blog, the facts don’t match the stereotype. The comments on this blog are very often the most interesting part. In fact, sites that allow comments usually find this to be the case, as readers identify items the writer missed, question basic assumptions, and add evidence from adjacent fields. I can’t count the number of times I’ve received a link to an article with a note appended reading, “The comments are the best part.” And it’s nearly always true. Most articles are actually the start of a discussion, not the end of one.

So my question is, When will this blogging stereotype go away?

The sad fact is that the answer is probably one of generational change. We’ve covered this before — whether print is an elite medium, or a medium for elitists. While there are bloggers in the senior corps of many fields, they tend to be rather quiet about their blogging, or they don’t stick with it long. It will be another generation before people with ingrained experience using digital-native publishing technologies are in the “old guard” of academia, publishing, and authority. By then, blogging will certainly be viewed as old-school.

Which is odd, because I thought it already was. From “Blog Wars” — a great academic book about blogs — to studies about attitudes about blogging, to how old the genre is, I thought people had already internalized this reality, learned to differentiate content from platform from author, and grown to appreciate the immediacy and craft of blogging.

Scholarly publishing in general has been comfortable with blogs for years now, from Health Affairs to Pediatrics to the New England Journal of Medicine. Are these not peer-reviewed? Are these not scholarly? These might not always look like blogs, and their editorial processes and approaches differ, but either from a technological, authoring, or social media perspective, they are at least kissing cousins to stereotypical blogs. And their editors and authors have embraced the potential blogs possess.

Even the most stringently peer-reviewed journal possible — the lofty Journal of Universal Rejection — has a blog summarizing some of the submissions and highlighting rejection letters. It’s well worth a read.

All this means is that blogs are downright legitimate editorial process and production tools.

Now, it’s tempting to say that perhaps this is just more of the same — that maybe printed books were greeted with the same disdain when they appeared, the scriptoria reviling them in the public square. Yet, this doesn’t seem to be the case. Not only does it seem that scriptoria worked hand-in-hand with the new printers — adorning their books to better create facsimiles of illuminated manuscripts, and so forth — but tradespeople and academics in the 15th and 16th century celebrated the printed book for what it was: a great new way to disseminate knowledge and opinion far and wide. At least, that’s what Elizabeth Eisenstein has found. And she knows a thing or two about these matters.

Are we perhaps more hidebound and conservative than our 16th century counterparts? Are we really that defensive? Can we not see what Michael Bhaskar described over two years ago?

Blogging is the signature written form of our age, indeed is arguably the most widespread and popular form of published words that has ever existed. Bracketing the arguments about noise to signal ratios, self indulgence and wild proliferation blogging is now a fact of the written word as much as letters, novels, newspapers and emails.

Like many disruptive technologies, a blog’s “weaknesses” — the quick-hit writing with links substituting for wordiness, the ability to generate content quickly, the ability to interact with an audience, the ability to write long or short, the embedded ability to link to and host multimedia, the participation of unexpected experts — are really its strengths.

Do blogs work? You be the judge. Just don’t be as demanding of evidence as Rodney Dangerfield’s father:

I remember the time I was kidnapped and they sent back a piece of my finger to my father. He said he wanted more proof.

Related articles

- How Live Blogging Has Transformed Journalism [Voices] (voices.allthingsd.com)

Discussion

19 Thoughts on "Blogging Dangerfield — When Will This Medium Get Some Respect?"

Thanks for this article. I can’t remember a time when I felt so validated, other than the occasional compliment for a grateful reader. As a blogger, or sometimes it feels like a slogger, I have been posting polished, critiqued essays for 4 years, carving out a little specialty niche, “how to read memoirs to help you write yours.” Where else would I have ever found a publication of hundreds of essays that have helped me (and hopefully my readers) learn so much about memoirs?

Having said that, I am keenly aware of the problem that there is no gatekeeper. To know my blogs are worth reading, you have to stumble upon them. And who has the time?

I like your notion of blog aggregators and hope to learn more. But some of the same problem applies. Where among the deluge do I find the right one?

I’m sure there are elitists who want to squash the whole thing, but even for us eqalitarians it’s difficult to know where to find the next great essay that speaks to us in tone and topic.

It’s like the fairy tale where the elf buried treasure under a tree and tied a ribbon around it to mark it. For some reason which I can’t recall, he later obscured his hiding place by tying a similar ribbon around every tree in the forest.

Sincerely,

Jerry Waxler

Index to 260 essays about reading and writing memoirs

Be patient! The medium is only about a decade old, and it has grown enormously, both quantitatively and qualitatively during these ten years. Of course, a number of stakeholders with interests in other media try to paint a negative picture. Wait ten years and see! (But then the medium has probably been substituted with something else.)

Kent: It sounds like you want blogs per se recognized as scholarly publications, in which case your cause is hopeless. Blogs are often political, like modern broadsides, and reviled as such by their opponents. Many other blogs are personal, or corporate.

Even Scholarly Kitchen is not scholarly. Being thoughtful and being scholarly are two different things, the latter being a specialized subset of the former. In science, blogs are most like the discussion that follows a conference presentation. This can be immensely valuable, but it is not scholarship, which is the careful presentation of research results.

So while blogging can get you recognized, it is not something to put on your resume to demonstrate scholarship. Activity yes, perhaps along the lines of organizing a conference, but not scholarship.

Next time an editor trashes blogging, use my curse — “I will make you famous.”

That’s really not my point, but let’s pursue it a little. Scholarly communications you can put on a CV have a lot of forms. A book chapter. An editorial. A letter to the editor. A rigorous peer-reviewed RCT. All of these things can be placed on a CV. Why not an editorial, chapter, letter published on a blogging platform.

And there’s the trick. Some of the major publications in the world are published using blogging technologies. The NYTimes is running on a high-end, highly customized version of WordPress. Some parts of NEJM are running on WordPress. The WSJ’s “All Things Digital” is a WordPress blog. Now, if I were to have an article published in any of those, would I be wrong to list that on my CV? Where is the boundary? Is it because there’s an editor approving the material? We do that here. Where is the line? Essays that likely would have appeared in other publications — and some that have subsequently appeared in other publications after being requested for reproduction — have appeared here.

So I ask you, given all that (and more), Where is this magical line of scholarship of which you speak?

I guess some of this discussion is troubled by a confusion between blogs as a kind of ‘media technology platform’ and blog as a ‘genre’.

In my humble view, the media technology platform is pretty uninteresting. As pointed out above, the same WP platform can be used for newspapers, academic journals and personal diaries.

What’s interesting is whether ‘the blog’ is a genre, a historically new kind of genre, like ‘the novel’, ‘the newspaper’, ‘the scholarly journal’, and so forth.

There is a long tradition of literary theory that defines genres as kinds of writing which are culturally constructed kinds in continuous negotiations between writers and readers. Genres aren’t fixed kinds of writing; they are flux, the borders are constantly negotiated, they evolve over time, they divide, fuse and mutate. And basically, they only *exist* as long as writers and readers behave as if they exist.

From this perspective, I think it’s way too early to discuss what blogs *really are*. A ‘blog genre’ wasn’t really identified until the early 2000s, and in the last ten years blogs have become what writers and readers negotiate them into becoming. Discussions like this one are of course influencing writers’ and readers’ perceptions of ‘the blog genre’ and thus contribute to the constant flux of ‘the genre’ and its equally fluent ‘sub-genres’.

This is really the trick here — a blog is both a technology and a stereotyped essay format (blustering, polarizing, unprofessional). But the platform component has gone mainstream painlessly. The evolution of the editorial aspect has not. I think that’s largely a difference in adoption and awareness. Blog software makes a lot of sense for IT people to use and extend, and it’s easy to master from nearly every perspective. Blog essays still live in the shadowland of uncertainty — what are they, where do they belong, are they any good?

With the editorial problems being clarified, I was just wondering aloud when the threshold of “blog as genre” might reach a point when people accept it. I think the answer is that it won’t, and perhaps the best bet is to begin talking about the “site” I run rather than the “blog” I run. After all, blogs hidden in other contexts (journals, newspapers, magazines) are part of those media, and are assessed as editorial products, not as technology indulgences.

So sensitive Kent….

Why should blogging be different from any other media? I can send you endless links about the lack of credibility of the “liberal media” or “Faux News”. Talk radio, with its slate of fringe lunatics is no more reputable. Even the top science journals are regularly derided as “glamor magz”. Are blogs somehow above criticism?

Personally, I think blogs deserve every bit of skepticism they receive. The barrier to entry is extremely low. Most are low-quality and short-lived. While some are high-quality, the signal is often lost in the noise of the conspiracy theorists, the birthers, the truthers, the anti-vaxxers and of course, those posting pictures of their pet cats. Other media are often less susceptible to such abuse, simply because the barrier to entry is much higher. You have to really want to show off your cat before you spend the money necessary to create a television network dedicated to doing so.

I will take this opportunity though, to highlight a pet peeve, something that instantly tarnishes any blog’s credibility in my eyes, and that’s the use of internet slang, the sort of spelling and phrasing common to LOLCats (“I can haz…” or “ZOMG!!!111!!eleven!!”). This was cute 5 years ago when 14 year olds were doing it while playing video games but if you want to be taken seriously, it does not help. It crops up surprisingly often in science blogs and is either an indication of immaturity of the writer, or a lack of individualism, a need to conform to community stereotypes (and outdated, cliched ones at that). It’s a failed and fairly pathetic attempt at elitism, an announcement that the author gets the inside joke of the slang, without actually realizing that this joke has long ceased to be funny, and the rest of the world has moved on. As soon as I see a “Z” substituted for an “S” or “teh” deliberately replacing “the”, I stop reading. It’s a phase that bloggers need to grow out of (and I freely admit that I indulged in my early blogging days before I felt confident in my use of the medium).

I welcome skepticism, and hold it forth in much that I read, no matter the medium. But the playing field should be more level. That was my point. To dismiss a vital communications medium out of hand without experiencing the high-end quality it can produce, without recognizing how it’s being used by reputable brands and writers, and without acknowledging that there is a range — to me, that has always struck me as a “head in the sand” approach, and I can’t respect it. Good and bad exist in all media — that’s not in dispute. What’s I dispute is the stigma that saying “blog” equates to immediate dismissal in some minds.

Be skeptical of the content. That’s fine. Just don’t dismiss the technology/form/medium out of hand, especially when you don’t understand it.

That’s a perfectly reasonable approach. But I’m saying the playing field is level. There are those who immediately dismiss anything on television news because they’re in the pockets of the big corporations, or anything in the NY Times because they’re the liberal media elite. Science journals can’t be trusted because they’re dependent on money from “big pharma”. There are lots of people out there who don’t have open minds and dismissing large swaths of information likely helps cement their already-chosen beliefs. Blogs being written off makes them like any other form of media.

Though as I noted above, the negative reputation for blogs is in many ways more deserved than some other forms of media, due to the low barrier of entry creating more noise than signal.

Your frustration is understandable, but perhaps at this point you’re asking too much from blogging and its audiences. Do blogs work? What kind of blogs? Crafts blogs most certainly work. They fostered a great community and offer a lot for those who are interested in crafting. Do blogs like scholarlykitchen work? What for? Their high-quality thoughtful essays are certainly a pleasure to read for educated people. But what is the role of such blogs in the media ecology? Do they want to be part of mass or scholarly communication?

This may not be clear for the larger audiences and that is why they can’t make up their minds. Perhaps, scholarly bloggers still need to clarify their own goals and roles and then join their efforts in challenging existing genres, criteria of quality, tenure procedures, etc.

I agree with this. Our role is to provide a timely and somewhat informed perspective on research, news, and trends affecting scholarly communication, and to cultivate a dialog with the wider community serving it. I think we’re fairly good at this, after a lot of work and experience.

This is one of the great things about blogs — they can spotlight experts. Great blogs in economics, foreign policy, medicine, and news already exist. Another comment noted that the low barrier to entry is a weakness of the medium. I’d counter that it’s a strength.

There are some good “scholarly” blogs, featuring well-argued opinion, which are worth reading. However, there are a lot more that aren’t- poorly argued, impulsive, etc. Life is short and from the consumer perspective it is a bit daunting to do all the filtering.

Most scientific publications (certainly those with any news element) run blogs and other social media initiatives alongside their more traditional content. If one wants to read about, say, the latest scientific research, it is quicker and usually better to use one of these outlets than to try to work out the reliability of an individual blog with no institutional or other obvious independent quality “stamp”.

That having been said, I enjoy reading well argued editorials posing as blog posts (eg this blog!). Very stimulating.

Kent

I read Scholarly Kitchen whenever I receive an alert about a new post. It is one of the first things I read each day. I link to the posts and alert colleagues about content.

This is an example of a trust network that supports blogging and any other form of communication. I think each of us can have these without status anxiety.

The issues you raise about blogging resonate with anyone who has been keen to use and promote qualitative research methods. Acceptance has been a long time coming from gatekeepers.

I do think bloggers have a provenance that invites long term commitment by readers. I am happy that the art of blogging is open to affiliation and choice. Great blog posts do find their place.

As ever, thank you for a delightful post.

Keith

My impression is that the success and reputation of blogging vary by sector. I am told, for instance, that there are some highly regarded blogs written by law professors that are equivalent (pace David Wojick) to scholarly contributions in the field. Maybe that’s because law reviews are not peer reviewed, so other forms of communication have an equal chance of being recognized as authoritative.

It’s nice to have some words of encouragement. Blogging can sometimes feel like sending out messages in a bottle!

People may have welcomed books printed using resettable type, but they led to the Protestant Reformation which split Europe into areas which encouraged reading and analysis and areas in which books were issued with approved interpretations, often in the form of inserts and overlays, or suppressed. The two groups often raised armies to kill each other for the next century or two. Printed books were an extremely disruptive technology.

I think print journalists tend to dismiss blogs out of jealousy. They have to toe a particular editorial line, and often one at variance to the own politics and even basic human decency. Imagine how they feel when someone else is doing just what they do, but they can follow up on stories, investigate further and publish their results freely. An MRI scan of the typical journalist would probably reveal a partially eaten liver.

Since I get most of my news from blogs, I find that I am much better informed than when I relied on the traditional media. I tend to know things before my more traditionally oriented friends, and I make better investment decisions. Yes, there are plenty of god awful blogs out there, but there are also plenty of god awful newspapers, and let’s not even talk about television “news”.

In defense of television news, I find that station WFAA in Dallas does some of the most impressive investigative reporting I’ve seen anywhere. It has won 7 Peabody Awards, more than any other TV station in the country.