I recently wrote a chapter for an upcoming book about academic and professional publishing. I’ve also written chapters in the past for other academic books about publishing. Writing a chapter is always a worthwhile experience — I like to write, I like the topics I’m selected to tackle, and I like the editors. But even with the books in hand, these chapters also seem to disappear under the waves like anvils, never to be heard from again.

So, the books sit on shelves, mute testimony to a spate of writing, editing, and aspirations — seemingly unlikely to generate the impact, buzz, reputation, or knowledge transfer I’d once hoped.

It seems I’m not alone.

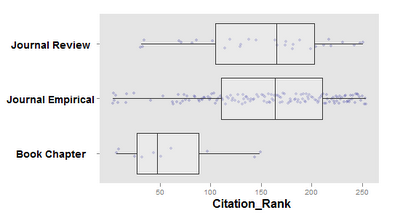

A recent blog post by Dorothy Bishop (a professor of developmental neuropsychology at Oxford, writing on her blog as Deevybee) explored how citations to academic book chapters fare in Google Scholar compared to citations to journal review articles and journal empirical (scientific) articles. While she expected a difference between scientific articles and book chapters, she was surprised to find a large difference between review articles and book chapters — after all, book chapters are akin to review articles, just published in a thematic book rather than a subject-area journal. Being competent with statistical software, she generated the following graph from her findings.

On average, book chapters generated about 1/3 of the citation rank of journal articles in her sample. Based on these relatively stark and grim findings, Bishop writes:

Quite simply, if you write a chapter for an edited book, you might as well write the paper and then bury it in a hole in the ground.

Why would this be? What factors would explain a lack of citations to book chapters, despite quality authors, interesting topics, important knowledge distillation, highly qualified editors, broad distribution, and prestigious publishers?

Bishop speculates that books suffer because they don’t have proper support from her three requirements for attention:

. . . there are three things that determine if a paper gets noticed: it needs to be tagged so that it will be found on a computer search, it needs to be accessible and not locked behind a paywall, and it needs to be well-written and interesting.

Bishop then notes that book chapters are often very well-written and interesting. She punts on the metadata issue, which I’ll return to. As for paywalls, we long ago worked out how to have everything discoverable behind paywalls. Nevertheless, for Bishop:

Accessibility is the problem. However good your chapter is, if readers don’t have access to the book, they won’t find it. In the past, there was at least a faint hope that they may happen upon the book in a library, but these days, most of us don’t bother with any articles that we can’t download from the internet.

I think this diagnosis of the relative obscurity of book chapters compared to journal articles comes up short in a number of ways, and with a poor diagnosis, the remedy won’t be quite right. Here are some other factors to consider:

- Books aren’t as available online as journal articles because they are put into different packaging. Journals long ago moved into the “article economy,” shedding the volume/issue shell for searchable articles, in every way except citation construction and print delivery. Books remain in a packaging shell, with chapters trapped therein. There is no “chapter economy.” This limits book metadata and searchability to often the shell components and not the muscle and sinew — aka, the chapters.

- Journals are broadcast on a regular basis, books are not. The common promotion of journal articles through email lists, print publication, aggregators, portals, journal clubs, and so forth creates much greater community awareness. Not only are the journal brands more predictable, constant, and “in your face,” the articles are anticipated on a weekly, bi-weekly, monthly, or quarterly basis.

- Regular publication means bigger metadata footprints. Books come out sporadically, with a changing cast of characters — topics, editors, authors, titles, subjects. Journals are more predictable, with editors, editorial features, and topics that repeat themselves regularly, expanding and deepening the property’s metadata with every new issue.

- New information supports awareness of companion content. The novelty contained in most scientific (empirical) articles draws media coverage for many journals, and high interest from the most passionate researchers and practitioners in the field. This magnetic pull also draws these same influential sources of awareness-building into the review articles, increasing reader and community awareness of these.

Bishop has raised a very interesting question for book publishers in this era — how and why are you at such a disadvantage in citation systems? Her request for publishers to address these deficiencies is also spot-on. But her diagnosis of the problem comes us short — as done mine, I’m sure.

Some publishers have modified their books into robust online properties, with regular updates, email lists, and so forth — O’Reilly, McGraw-Hill, and others. Perhaps authors should become more selective, preferring these properties to bounded, sporadically published editions. After all, the impact difference that’s at stake may be sizable.

Discussion

33 Thoughts on "Bury Your Writing — Why Do Academic Book Chapters Fail to Generate Citations?"

I conjecture a different view. First you need to analyze a fourth case, that of conference proceedings. These are like books in that they have something like chapters, by different authors. But they are time sensitive, like journal articles. My conjecture is that they too are less ctied than articles, but more cited than books.

The likely reason for all this is the degree of filtering, which measures importance. Empirical articles have the highest rejection rates, while books have, or are thought to have, the lowest. Book chapters are seldom rejected. Proceedings are likely in the middle because they invited you, or let you in, before they knew what you were going to say.

It all makes good sense if filtering via rejection is the principal value of the publication system. Discovery has little to do with it. Prestige is the dominant parameter and one tries to cite the most prestigious sources. But this is just a conjecture.

This paper studies the use of conference proceedings in one area of engineering and might be useful for this discussion.

Tracking the use of engineering conference papers: citation influence of the Stapp Car Crash Conference. By: McMinn, H. Stephen; Fleming, Kathleen. Collection Building, 2011, Vol. 30 Issue 2, p76-85, 10p; DOI: 10.1108/01604951111127443 E-Journal Full Text

It’s not a question of access, it’s a question of discoverability. Most researchers, through their libraries or their own funds, can gain access to a book. But they have to know that book exists. In medicine and the life sciences, if the full text of the article is not in Google or PubMed, it’s unlikely most will ever find it.

That’s why, years ago at CSHL Press, we converted several of our long-running book series into journals. CSH Protocols (http://www.cshprotocols.org) was the first, given that when queried about where they found their laboratory methods, scientists almost always responded, “Google.” This has (since my departure) been followed by highly successful review journals, CSH Perspectives in Biology (http://www.cshperspectives.org) and CSH Perspectives in Medicine (http://perspectivesinmedicine.org/), both created from CSHL’s long-running monograph series. The content of these journals is still available in collected book form for those who prefer it that way.

There’s also a real benefit in this approach as it’s much, much easier to get authors to write an article for a PubMed-indexed, Impact Factor-having journal than it is to get them to write a book chapter. There seems, at least in these fields, to be greater career credit given for the journal article than a book contribution.

I agree that the problem is “Discoverability” and electronic access. Here is another reason why book publishers should make their content available to academic libraries as ebooks, AND supply the full text of the book content to the library discovery systems such as Summon.

Students (and dare I say faculty) increasingly forgo materials they have to leave their seat to retrieve. If the chapter is discoverable in their library’s discovery system, and they can link to the chapter of interest immediately they are more likely to use the content.

Reblogged this on apropos science.

David Wojick’s speculation may be true for edited books in science; it is not true for edited books in the humanities and social sciences, which are put through just as rigorous a review process as any single-authored book is. As part of this review, any seriously deficient chapter is likely to be dropped as a condition of publication.

Until very recently, book chapters were not assigned DOIs, as journal articles are. But increasingly they are, and this will help with discoverability. So too will the cross-searchability between book and journal content in such aggregations as the UPCC.

There are two fundamental weaknesses with Bishop’s citation comparison:

1) She assumes that the quality between format sources is equal — it is not (see: David W’s comment)

2) She assumes that Google is a reliable and valid source of citations. — it is not. This is apparent from the figure where empirical journal articles do as well statistically as review articles. This should have thrown up a red flag.

Access to a document an important antecedent to citation, but there are more important factors at play (i.e. relevance, discoverability, and quality). Thankfully, self-selection and editorial selection tends to concentrate them all.

It depends on what your definition of a book is. Lots of researchers contribute chapters to http://www.annualreviews.org which are considered to be books by many libraries and individuals, but they are indexed as if they are journals in many databases. The Annual Reviews are highly respected publications with high IFs for the most part. So, what are they? Are they books or journals?

Whether Bishop’s diagnosis is correct or not, her behavioral self-report is important:

these days, most of us don’t bother with any articles that we can’t download from the internet.

This is yet one more reason why the ecology of the net favors open access. It may also explain why, when journals are canceled, they are rarely missed: people just move on.

…or, why librarians need to do a better job identifying and purchasing access to those journals that their constituents want to read. Ivy, I hope you aren’t giving up on the value of librarians and the academic library.

… or, why librarians need to move more decisively towards a model in which their patrons’ access horizons aren’t limited by what librarians have guessed they’re going to want. This implies patron-driven acquisition–and I guess it does, in fact, imply giving up (at least partially) on one traditional role of librarians and the academic library: that of preemptive selector.

It’s interesting that “articles that we can’t download from the internet” equals “things I don’t pay for”. I can buy books over the Internet via Amazon, but I pay for them. Nothing wrong with that. Why is paying for content not part of the “ecology of the net”? PayPal and eBay might disagree, as might Amazon, New York Times, and so forth. The ecology of the net might favor neither.

Reblogged this on tressiemc and commented:

From the end-user side the meta-deta and format comments on this great post make the most sense. Like many people, I rely upon internet databases to do research. Academic edited volumes rarely have per chapter tagging. So, the book may not be tagged according to my interest or search because it is too broad. And there is no tagging for the chapter that would have been helpful. And, if I do find the chapter rarely can I read it online, even when using university library proxies. They simply don’t scan chapters that way. That means a trip to check the book out. While I do that frequently I can understand being in the field or working on a diss from afar and that being a roadblock. Finally, why aren’t academic volumes routinely in e-formats? And even when they are why are they so damned expensive?? $80 for an e-book is not uncommon in my experience. That’s for a chapter I’m not sure I need because I can’t read it beforehand, by the way.

From my experience, the prices are high simply because of economies of scale. A popular fiction/non-fiction book can cover costs with a low price because it’s expected to sell tens of thousands (if not hundreds of thousands) of copies. Most scholarly works are only going to appeal to a much smaller audience (and many can only be read by a tiny audience with the background knowledge to make the work comprehensible). If you’re only going to sell 500 copies of a book (and for some books, that may be a stretch), then you have to charge more per book to recover your costs.

Remember also that scholarly works have expenses that other types of books often don’t–fact checking, reference checking, licensing of figures and images for re-use from previous publishers, color printing, etc. Only the last of these costs goes away when you move to a digital format.

As Sandy Thatcher mentioned above, university presses and other scholarly publishers have recently gained the opportunity to start placing academic monographs and edited collections in aggregated collections such as Project Muse, JSTOR, and others, where chapters are now tagged for searchability. This is all very new, less than a year old. Also, generalizations about STM books and journals do not apply across the board to all disciplines, which do not all measure influence based on citations and impact factors. Consider whether a book, article, or chapter is used in classroom teaching, discussed in conference papers and panels that are never published as proceedings, or discussed at length in influential (non-journal) media like the London Review of Books, Times Higher Education Supplement, New York Review of Books, or Chronicle of Higher Education.

The business model of books compared to journals also plays into this. With books it’s a one-off marketing push, before and around publication. Then maybe some cluster work in the next 6-12 months. Then move on to the next book.

There is also no incentive to promote usage of the book once it’s been bought. (Cynically, the reverse is true; if people forget they have the last book on this topic they might be the new one…)

With journals it’s a continuous push of articles to drive ‘usage’, to drive citations. To drive an impact factor.To drive resubscription.

With books it’s make the sale. Move on.

The business incentives are different. If the book impact factor ever gets off the ground then maybe this will change. Maybe PDA will drive some changes here as well. (Has Joe Esposito looked at this in his project?).

There is, however, a substantial use of book chapters for course use, as revealed through CCC permission payments.

I think the most basic answer to this question is that most books are not in CrossRef and don’t have DOIs, especially not chapter-level DOIs. This is changing, and CrossRef is working on helping to change this, but the reality is that right now, especially outside of STM (and unfortunately often still within STM), book publishers just don’t think about this. They are fixated on _distribution_ (and the eCommerce and DRM issues associated with the selling of books) to the detriment of _citation_. I do a lot of work with book publishers (many or most of them scholarly or academic in nature) and you would be absolutely shocked at how often I hear the phrase “what’s a DOI?” I’m not kidding!!!

I firmly believe that the rapid transition from print to online for journal content was catalyzed by CrossRef, which provided the ability to cite and link to cited resources (at first overwhelmingly journal articles), which then in turn put pressure on publishers to make those resources available (under whatever commercial arrangements) online. Now if a journal article is not online and doesn’t have a DOI it’s virtually invisible; put another way, virtually all journal articles ARE available online, DO have DOIs, ARE in CrossRef. This has simply not yet happened in books, to a sufficient extent. But it’s about to. How can it not?

No more invisible book chapters, people!

My employer (I work at Springer, my opinions here are my own) has been working with large volumes of eBooks since 2005. In that time, I’ve noticed a few things…

First, most of the books I see coming across (both in the consideration stage and also when I’m staffing a booth) tend to be of a “tutorial” nature. Many are lecture notes and pedagogical/self-study (even when they don’t have adoption potential). Most, I would suggest, get used by people needing to come “up-to-speed” on a particular area. And not necessarily faculty/researchers, advanced undergrad and graduate students. Ergo; much use on campus, not many cites. We can see this in download patterns, And if students not yet ready to begin publishing are using, then chapter downloads, rather than cites, would be the measure.

Secondly, I think with full text Google indexing, many monographs grow very, very long tails.

In my STM field, Springer has done a very good job of making book chapters discoverable through SpringerLink, as easily as any journal article. It would appear to me that this kind of common platform for journals and books has a lot of potential, and Springer is making good use of it.

If we’re touting new, forward-looking platforms, I’ll put in a plug for OUP’s University Press Scholarship Online (http://www.universitypressscholarship.com/), just joined by the University of Chicago Press, along with The Oxford Index, an offspring of an enormous metadata cataloging effort by OUP that has done wonders for increasing discoverability of book content through search engines like Google (http://oxfordindex.oup.com/).

I think many book publishers were afraid of Google; but cooperating with Google has actually helped discoverability and also, even, print sales.

Of course, even in the mid-90s when I worked there, OUP always had a pretty good handle on book meta/catalogue data. 🙂

Kent, I enjoy your posts. Thanks for your insights.

Your analysis on chapters vs. articles is interesting. I believe that your first reason — that differences in packaging result in “searchers” finding articles more easily — is a major driver, perhaps the major driver, of the difference in citations favoring articles over chapters. Even so, there may be a few other reasons for the phenomenon you observe, at least in our specialty of orthopaedic surgery. Perhaps

-The kinds of people who buy books are different from the kinds of people who write book chapters and articles; the former (trainees, practicing surgeons) are more apt to be content consumers, while the latter (academicians) are more likely to be your generators of citations.

-Related to this, the kinds of content found in books often are different from those found in articles. Book content is more likely to be review-type content, or “synthesis” (and usually old-school review content, rather than meta analysis or systematic review); article content is more likely to be (or perceived to be) related to “discovery.” Perhaps the kinds of people doing the citing are more drawn to the latter than the former, as it is, or is perceived to be, more current or useful in those individuals’ own ongoing projects; and

-Journal articles are more likely to be peer reviewed, and so may be (or be perceived to be) of better quality. I’ve never had a book chapter turned down, though — I’m embarrassed to say — sometimes my manuscripts have been turned down by journals…

Again, Kent, I look forward to your posts. They always are thoughtful, and you do a great job of finding interesting topics to shine a bright light on. Keep it up!

that’s a very interesting finding.

The whole purpose of writing is to get an audience to read it.

So to speak, I guess it’s better to avoid publishing chapters in edited books, instead targeting a journal would work better. After all a chapter in an edited book is more like a review paper.

But when I think about it, I think I’d rather go for a book, if it is more like a review.

And to be honest, a book looks better on my bookshelf 🙂

I relish the feel of a book.

I guess we just need promote our chapters using appropriate media.

I don’t think I would agree that you have less of an audience–reading–in books. I suspect that it is a different audience than with journals, and an audience that isn’t itself publishing/citing. E.g., students, etc.

I do find interesting that many of these discussions–including about the roles of librarians–forget about students, especially when on average in U.S. institutions they outnumber faculty by around 15:1 (U.S. News, http://www.usnews.com/education/best-colleges/articles/2011/04/26/liberal-arts-colleges-with-lowest-student-faculty-ratios)

I agree SJ. The primary purpose of citations is to explain the scientific background for the research being reported. This usually means a combination of the seminal papers, one’s immediate predecessors, one’s self, and sometimes one’s competitors. Prestige and economy demand that only the most important sources be cited, which tends to exclude book chapters. It does not mean that no one is reading the books, far from it.

Very interesting article. And for us at Slicebooks, interesting timing. (disclaimer: I am a co-founder) My apologies if the following sounds like a “sales pitch”. It is not meant to be…only to provide information about one platform that is currently available, and addressing the need for chapters (sections, pages, etc).

We began our journey in digital content by launching an ebook store a few years ago with the intent of offering content “whole or sliced” – meaning that customers could come to eBookPie, purchase an entire ebook or just the chapters they need. It all started based on our careers in publishing, but also because of a passion for travel and wanting to be able to only purchase chapters from different travel publishers only for the cities we were visiting instead of 5 books about Mexico (for example).

Publishers thought it was a great idea when we talked to them, but at the time, they were busy converting from print to digital. So we walked away and thought there had to be a way for us to make this easy for publishers. We developed Slicebooks, which lets a publisher upload ebook files (ePub or PDF), and slice them into fully-packaged, ready-for-sale sections, chapters, sub chapters – even pages. We launched in beta in June and are getting great feedback (new version to launch in mid-September).

Publishers ask, “why?”. Here’s some of the reasons we tell them – https://slicebooks.com/pages/why_slice_and_remix

The interesting part (we think) about Slicebooks is it includes a tool that allows publishers to select slices from different sources, and create a remix (ie. new ebook). Academic publishers see many uses for the remix tool, as do religious/spiritual book publishers and others. This tool will soon be available to publishers and retailers to have on their own sites so their customers can purchase and remix content.

As you might have guessed, we built Slicebooks to help populate our ebook store to fulfill our quest to provide content to customers just how they want it – whole or sliced. Here is one example: https://ebookpie.com/ebooks/176392-beginning-iphone-sdk-programming-with-objective-c

So I think the pursuit of discoverability for all content continues to change and expand. Publishers continue to explore new ways for getting vetted, edited, quality content in front of people.

Reblogged this on Progressive Geographies and commented:

Some interesting discussion here of book chapters vs. journal articles. Citations should never be the only measure, but not being read is surely a problem for many collections.

The motivating community is just worth comment. I Do think that you must present lots more regarding this

problem, might possibly not be a restrict subject however generally everybody do not speak so much about those subjects.

To put in a bit benefit I’d like to give couple facts: plate installed forge vitality machines are actually extremely good, eat long to remain slim